BACKGROUND

Self-concept clarity is the degree to which the contents of an individual’s self-concept are internally consistent, temporally stable, as well as clearly and firmly defined (Campbell et al., 1996). Unlike self-concept that focuses on content, self-concept clarity emphasizes the coherence of its structure (Schwartz et al., 2012). Low self-clarity in adults suggests inconsistency in self-perception, identity instability, and feelings of disconnectedness (Paetzold & Rholes, 2021).

Stronger self-concept clarity in adolescents and adults is linked to improved subjective well-being (Xiang et al., 2023). This association likely arises from clearer goal setting and reduced stress/depression (Coutts et al., 2023), even promoting healthier gaming habits (Green et al., 2021). The positive link between self-concept clarity and meaning in life has been reported among Turkish university students (Çebi & Demir, 2022) and Chinese nursing students (Hong et al., 2022). In one cross-cultural study, self-concept clarity had no significant link to the psychological outcome in a collectivistic culture, but a significant correlation was observed in an individualistic culture (Quinones & Kakabadse, 2015). Interestingly, a study documented that East Asian and Southeast Asian participants tended to score lower on self-concept clarity than other racial samples (Cicero, 2020). However, self-concept clarity still serves as a critical factor in elaborating one’s global self-worth among Chinese (Wu et al., 2010).

China and Indonesia, both with large populations from East and Southeast Asia, share a collectivistic culture. In collectivistic cultures, which value flexibility, adaptability, and social harmony, changes in one’s self-concept are less harmful to overall well-being compared to individualistic cultures (Haas & VanDellen, 2020). While meaning making is intertwined with cultural values (Alea & Bluck, 2013), and different cultures perceive the meaning of life differently (von Humboldt et al., 2020), research often focuses on Western society or compares individualistic and collectivistic cultures, overlooking variations within collectivistic communities. For example, 93% of Indonesians consider religion important in their lives, whereas only 3% do in China (Pew Research Center, 2019). Some studies found that religiosity plays a key role in life satisfaction and meaning in life (Jung, 2018; Pastwa-Wojciechowska et al., 2021). Therefore, differences in religiosity might influence how Indonesian and Chinese emerging adults perceive the clarity of oneself and its implications for their well-being. Little research has studied self-concept clarity and its outcomes cross-culturally among Asian communities.

Our study examines the impact of self-concept clarity on purpose, life satisfaction, and personal meaning in young adults aged 18-25 in China and Indonesia, as it has been found that individuals with higher self-concept clarity exhibit more adaptable personality traits (de Moor et al., 2023). Most studies in Indonesia have explored self-concept, but only one study reported that self-concept clarity negatively predicted thesis writing procrastination (Tuasikal & Patria, 2019). Studies on self-concept clarity among Chinese are more common as a predictor of wellbeing (Lin et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2022). It is hypothesized that self-concept clarity will predict purpose in life, life satisfaction, and personal meaning in Chinese and Indonesian emerging adults.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Participants aged between 18 and 25 years old comprised 248 Indonesian college students (78.2% were female, with average age 19.30, SD = 1.30) and 311 Chinese college students (75.9% were female with average age 20.40, SD = 5.04). No significant differences were observed between the two samples. These participants were recruited through convenience sampling. The Indonesian participants were offered to join a lucky draw to win a top-up bonus for a digital wallet, worth US$1.5. The Chinese participants received a souvenir, worth US$2.

PROCEDURE

Data collection was conducted through an online survey. Ethical clearance was obtained by the local ethics committee in each university. The research conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent.

MEASUREMENTS

The Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) measures the degree to which one’s self concept is deemed clear and consistent. The scale consists of 12 items which are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The regression coefficient of self-esteem (β = .35, p < .001) as well as internal state awareness (β = .61, p < .001) on self-concept clarity was positive and significant (Kruse et al., 2017). The Self-Concept Clarity Scale was translated into Indonesian using forward translation by four undergraduate psychology students under supervision of the researchers.

Claremont Purpose Scale (CPS). This 12-item scale was developed to measure long term intention to pursue meaningful aims for oneself and others (Bronk et al., 2018). The CPS comprises three dimensions, namely personal meaning, goal directedness, and beyond-the-self orientation. The CPS has been adapted and validated into the Indonesian context (Yuliawati, 2022). The CPS was translated into Chinese by two psychology lecturers from a university in Southeastern China. This scale has a Cronbach’s α coefficient = .94 and positive correlations with empathic concern (r = .50, p < .01) and wisdom (r = .62, p < .001). Participants rated on a five-point Likert scale with varied response options (e.g., 1 – not at all clear or almost no effort, 5 – extremely clear or a tremendous amount of effort).

The Personal Perceived Meaning Scale (PPMS) assesses one’s perception of how significant one’s life is (Wong, 1998). Each of 12 items is rated on a nine-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). A previous study translated and reported that Cronbach’s α for the Indonesian version of the PPMS was .89 (Yuliawati, 2018). The Chinese version of the PPMS was translated by two psychology lecturers from a university in Southern China.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) comprises 5 items to measure to what extent one feels satisfied with one’s life (Diener et al., 1985). Participants rated their responses using a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Indonesian version of the SWLS had good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α of .83 (Yuliawati, 2018). We used the Chinese version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale from Bai et al. (2011).

Reliability analyses and confirmatory factor analyses were performed for each scale in the Indonesian and in the Chinese data, respectively. As presented in Table 1, all scales had good internal consistency. Spearman correlation was used since the data were not normally distributed. All variables had a positive correlation, except that self-concept clarity had no significant correlation with purpose in the Indonesian sample. It should be noted that items 3, 6, and 11 from the Self-Concept Clarity Scale were deleted due to low factor loadings and low corrected item-total correlation.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of all variables in Indonesian and Chinese data

Since neither the Indonesian nor the Chinese data are normally distributed, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used. The suitability of the model was assessed using several fit indices with the following cutoffs: For the robust comparative fit index (R-CFI) and robust Tucker-Lewis index (R-TLI), values above 0.95 were considered a good fit to the data, and values above 0.90 were considered an acceptable fit. For robust approximate mean squared error (R-RMSEA), values < 0.06 indicated a good fit while values < 0.08 indicated an acceptable fit. For standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR), values below 0.10 indicated a good fit to the data (Matsunaga, 2010).

Confirmatory factor analyses of each scale were performed in each sample. As can be seen in Table 2, the Self-Concept Clarity Scale and Perceived Personal Meaning Scale showed an acceptable fit to the Indonesian and Chinese data while the Claremont Purpose Scale showed a good fit to the data.

Table 2

Confirmatory factor analyses of all scales in each sample

DATA ANALYSES

Analyses were conducted using RStudio 1.3.1093 with the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) and semTools (semTools Contributors, 2016). A multi-group CFA was performed to test the invariance of measurements between Indonesian and Chinese samples (Dimitrov, 2010; Sass, 2011). In the configuration-invariant model, the factor structure was constrained to be the same across groups, but all parameters (factor loadings, item sections, item residual variances, latent variable variances) were allowed to differ between samples. After configuration invariant models were established, the weak invariance model was compared to the configural one. If there was no significant deterioration, indicated by ΔCFI between measurement invariance models being ≤ .01, ΔRMSEA ≤ .015, and ΔSRMR being ≤ .030 (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), weak or metric invariant models could be established.

The third step to assess measurement invariance is to test a strong or scalar invariance model that fixes the factor structure, element factor loadings, and the same intercepts for the two participant groups, and subjects them to a comparison with the fit index of the weak invariant model. Next, in a strict or residual invariance model, factor structure, factor loadings, intercepts, and residual variances were constrained to be invariant across countries. We compared the fitness indices of the scalar and strict invariant models to assess the feasibility of building a strict invariant model.

RESULTS

Following the procedures in the data analyses, the configuration-invariant model was tested first, and the fit index showed an acceptable fit (R-CFI = .914, R-TLI = .906, R-RMSEA = .051, SRMR = .067). The factor structure of each variable was similarly perceived among emerging Indonesian and Chinese adults. A weak invariant model also showed a mere fit to the data (R-CFI = .906, R-TLI = .901, R-RMSEA = .053, SRMR = .072). The difference in these fit indices did not exceed the cutoff values (ΔCFI = .008, ΔRMSEA = .002, ΔSRMR = .005); thus weak invariance can be observed. A strong invariant model was tested, but the fit index was poor (R-CFI = .858, R-TLI = .854, R-RMSEA = .064, SRMR = .080). This means that only the regression coefficients of subsequent models can be compared across samples.

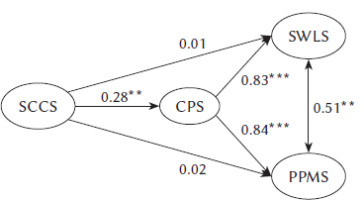

Figure 1 shows the results from the Indonesian data which provided an adequate fit to the data (R-CFI = .92, R-TLI = .91, R-RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .07). Self-concept clarity positively predicted purpose in life (β = .28, p = .003) but no significant correlations between self-concept clarity and life satisfaction and personal meaning were observed. Purpose in life had a strong correlation with life satisfaction and personal meaning.

Figure 1

Relations among the variables self-concept clarity, purpose in life, and well-being in the Indonesian data

Note. SCCS – Self-Concept Clarity Scale; CPS – Claremont Purpose Scale; SWLS – Satisfaction with Life Scale; PPMS –Perceived Personal Meaning Scale. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficient. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

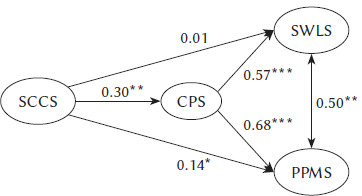

As shown in Figure 2, the model in the Chinese sample barely fit the data (R-CFI = .91, R-TLI = .90, R-RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .08). Similar to the Indonesian sample, self-concept clarity had a significant positive association with purpose in life and purpose in life positively predicted life satisfaction and personal meaning. Interestingly, self-concept clarity showed a positive correlation with personal meaning only in the Chinese sample.

Figure 2

Relations among the variables self-concept clarity, purpose in life, and well-being in the Chinese data

Note. SCCS – Self-Concept Clarity Scale; CPS – Claremont Purpose Scale; SWLS – Satisfaction with Life Scale; PPMS –Perceived Personal Meaning Scale. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficient. *p ≤ .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

The study explores the role of self-concept clarity in purpose, personal meaning, and life satisfaction in Chinese and Indonesian emerging adults. Corroborating prior studies (Bigler et al., 2001; Light, 2017; Schlegel et al., 2011), we found that self-concept clarity positively predicts purpose and facilitates self-regulation and goal pursuit in both samples.

Understanding one’s uniqueness is crucial for pursuing relevant goals (Pilarska, 2016) and increasing empathy (Krol & Bartz, 2022). Empathic concern correlates with purpose, as individuals can identify others’ needs and contribute to their future aspirations, involving beyond-the-self orientation (Bronk et al., 2018). The benefit of purpose in life for life satisfaction in both Indonesian and Chinese young adults corroborates another finding in the Asian context with a collectivistic culture: individuals aiming to satisfy themselves and others were more likely to enjoy life satisfaction than their counterparts pursuing only a self-oriented or other-oriented purpose (Heng et al., 2017). It is also suggested that in the long run, action motivated by a prosocial motive becomes the meaning of life (Oleś & Bartnicka-Michalska, 2021).

Purpose in life shows a stronger correlation with personal meaning and life satisfaction in the Indonesian sample than in the Chinese sample. Recent studies propose purpose as a facet of meaning in life, but emerging adults might understand that purpose and meaning overlap, with purpose as a means to obtain meaning (Ratner et al., 2021). Having a purpose in life for Indonesians may provide a better guarantee for enjoying life satisfaction and personal meaning, as these constructs are closely linked. A meta-analysis indicated that the presence of meaning strongly predicts subjective well-being in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures, while the search for meaning is only a positive predictor of subjective well-being in collectivistic cultures (Li et al., 2021). Searching for meaning may offer additional benefits for increasing life satisfaction among Chinese individuals.

In the Chinese sample, self-concept clarity and the presence of purpose serve as significant predictors of meaningfulness. Chinese people are influenced by three major beliefs. Confucianism prioritizes social harmony by teaching people about the pre-existing individual duty in society and how to fulfill their role (Lin, 2001). This belief makes Chinese people already understand their goals to contribute to the country, thus making them focus more on self-growth (Ge et al., 2022). Meanwhile, Taoism and Buddhism teach that the contentment of oneself is attained by understanding oneself and accepting the flow of life that is directed by personal experience in ordinary life (Dekabrskiy, 2019). Therefore, as long as one can experience life events and be connected to the universe, meaning can be obtained with or without any purpose.

Purpose in life is more important in Indonesian emerging adults than in the Chinese. Chinese values, such as social connections and personal growth, are associated with higher well-being (Wang et al., 2021). In contrast, Indonesian youth prioritize social recognition and self-indulgence, demonstrating a strong desire for interaction and validation from peers (Helmi et al., 2021). Even though China and Indonesia both are collectivistic countries, they exhibited different ways to take value from the community (Sari et al., 2021). Becoming someone with a clear and normative purpose makes Indonesian emerging adults able to gain both self-fulfillment and social recognition which eventually brings meaning and satisfaction in their life (Jadidi et al., 2019; Maulana et al., 2018).

In both countries, no significant link between self-concept clarity and life satisfaction was found. Various life events during emerging adulthood as a transition period (Lodi-Smith et al., 2017) may explain this, as they explore identities and reevaluate goals. Our results suggest that life satisfaction requires both self-clarity and purpose, aligning with the finding that purpose is a key component of well-being for emerging adults (Glanzer et al., 2018).

SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study is the first to examine how identity and purpose influence wellbeing in Indonesia and China. It provides valuable insights, suggesting that even within collectivistic cultures, the importance placed on self-concept clarity regarding purpose and personal meaning can vary among emerging adults. Though purpose and meaning have been examined separately in recent studies, emerging adults may differ in the extent to which they conflate these concepts.

In this study, configural and weak invariance were established, but strong invariance was not supported, preventing a direct comparison of latent factor means across groups. Future cross-cultural research should aim for partial strong invariance using alignment methods to identify varying parameters (Marsh et al., 2018). This study notes sociocultural differences between China and Indonesia, yet it needs to add more sociocultural variables to emphasize the differences, such as social identity and religious belief. Income also correlates with subjective well-being (Diener et al., 2013; Easterlin, 2013; Oishi & Diener, 2014); thus future studies could explore these variations further.

CONCLUSIONS

This study revealed a noteworthy finding that self-concept clarity is a significant predictor of purpose in life, leading to life satisfaction and personal meaning in both Chinese and Indonesian cultures. In collectivistic cultures, individuals aim to contribute to others’ welfare, fulfilling both individual and societal life satisfaction. In Indonesia, purpose in life is stronger, possibly due to the younger generation prioritizing recognition by peers. Despite their collectivistic tendencies, both countries have distinct approaches to personal meaning. Chinese individuals perceive self-concept clarity as a means to contribute to their societal roles, while Indonesian adults align their self-concept clarity with personal purpose.