BACKGROUND

Adolescents are prone to mental health issues, including stress, anxiety, and depression (Racine et al., 2021; Meyers et al., 2021; Wiederhold, 2022). It has been elucidated that during adolescence, there is a heightened vulnerability to the emergence of mental health issues such as depression (Thapar et al., 2012). Mental health problems among adolescents have been reported in Hong Kong (Yuen et al., 2019), Korea (Jeon et al., 2020), China (Chi et al., 2021), Taiwan (Jhang, 2020), Bangladesh (Moonajilin et al., 2020), and Indonesia (Kaloeti et al., 2019). The mental health challenges encountered by adolescents can be attributed to a variety of factors, including exposure to acute stressful events such as personal injuries and bereavement, as well as enduring chronic hardships such as poverty, bullying, family conflicts, abuse, and physical illness (Badr et al., 2018; Collishaw, 2015; Eyuboglu et al., 2021; Thapar et al., 2012). Research by Mojtabai et al. (2016) demonstrated that the occurrence of major depressive episodes among adolescents and young adults primarily affected those between the ages of 12 and 20 years old. The study revealed that gender played a role in the onset of mental health issues among adolescents, with girls displaying higher levels of depressive symptoms and experiencing major depression episodes more frequently than boys (Anyan & Hjemdal, 2016). In their research, Kelly et al. (2018) found a more pronounced link between social media usage and depressive symptoms in girls compared to boys. Research on the relationship between internet use and adolescent mental health has become a priority in recent years (Hoare et al., 2017; Kaya, 2021; Keles et al., 2020). According to survey data conducted by the Indonesian Internet Service Provider Association (2020), 196.7 million people (73.7%) had accessed the internet in Indonesia. The increased internet and smartphone usage can lead to negative consequences, including addiction. Research has demonstrated that excessive social media use can detrimentally affect psychological well-being and exacerbate mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress (Keyte et al., 2020). According to the Indonesia National Adolescent Mental Health Survey (I-NAMHS), which is the first nationwide mental health survey assessing mental disorders in Indonesian adolescents aged 10-17 years, it was found that one out of every three Indonesian adolescents, totaling approximately 15.5 million individuals, is grappling with mental health issues. Among these, the most prevalent mental disorders among Indonesian adolescents were anxiety disorders (Gloria, 2022).

Barry et al. (2017) proposed that there is a positive correlation between the number of social media accounts adolescents have and the frequency with which they check these platforms, and the sensation known as fear of missing out (FoMO). FoMO is defined as an individual’s perception that others may be enjoying meaningful experiences in their absence, leading to a desire to stay connected and keep up with what others are doing (Przybylski et al., 2013). Research has revealed that FoMO is associated with the extent of problematic smartphone use and a higher frequency of gadget utilization (Elhai et al., 2018, 2020). A high level of FoMO is also linked to mental health challenges in young individuals, including heightened anxiety levels and reduced life satisfaction (Roberts & David, 2020; Servidio, 2023). Theories regarding FoMO relate to various negative experiences and feelings, because they are considered a problem of excessive attachment to social media (Gupta & Sharma, 2021). However, various studies have not been able to explain the direction of the relationship between these variables (Gupta & Sharma, 2021; Liu et al., 2019). Further, it is connected to mental health problems and social functioning including individual resilience abilities (Gupta & Sharma, 2021).

Various studies have shown that resilience was a protective factor against young’s mental health conditions (Liu et al., 2019; Taş, 2019; Yuan, 2021). Resilience is the capacity of an individual to bounce back, recover, thrive, and adapt when confronted with adversity (Zhao et al., 2020). Kaloeti et al. (2019) demonstrated that resilience had a direct impact on depressive symptoms and also acted as a partial mediator in the relationship between psychological distress and depressive symptoms among adolescents.

This research aimed to determine the link between resilience and symptoms of depression and anxiety in Indonesian adolescents, particularly the extent to which FoMO mediated resilience to symptoms of depression and anxiety.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Participants in this research were selected by simple random sampling with three criteria, namely being adolescents (12-18 years), actively using social media, and being willing to be a research participant by signing an informed consent form. A total of 509 Indonesian adolescents aged 12-18 (M = 15.89 years, SD = 9.64) participated in this research, consisting of seven schools in several provinces in Indonesia. A slight majority were boys (n = 274; 53.83%), with 235 (46.17%) girls. Most were senior high school students (n = 334; 65.62%). Almost all (n = 501; 98.4%) were of Javanese ethnicity.

PROCEDURE

The participants were informed of the research objectives and methods. They gave their consent to participate before taking part in the study, which was voluntary. They could withdraw from the study at any time. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. For participants under 18 years old, the informed consent came from parents/legal guardians/kin. The research was granted approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the Diponegoro University, Semarang (approval number 282/EA/KEPK-FKM/2021).

INSTRUMENTS

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC 10). The level of individual resilience was measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) consisting of ten items (example of item: “I can adapt to the occurring changes”) where responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007) modified it from the original scale of 25 items (Connor & Davidson, 2003), and it was reported to have good psychometric properties and unidimensional factors in adolescent and young adult participants (Notario-Pacheco et al., 2011). The total score obtained from the first 10 questions of the CD-RISC 10 indicates the individual resilience. The higher the score is, the higher is the level of resilience. The score can be classified into four categories – low (0-29), moderate (30-32), high (33-36), and very high (37-40) – as described by Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007). The reliability of the CD-RISC 10 in this research was determined to be .87 using the alpha coefficient.

Fear of Missing Out. The Fear of Missing Out Scale (FoMO), adapted from an original scale by Przybylski et al. (2013), was used to measure the pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one was absent. The adapted scale comprised ten items (e.g. “I get anxious when I do not know what my friends are up to”) where the responses ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (extremely true). A higher score (ranging from 10 to 50) denoted a higher level of FoMO. Cronbach’s α for this scale was .90.

Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). The Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was used to evaluate the negative emotional state (depression, anxiety, and stress) of the participants. It consists of twenty-one items (example of item: “I feel that I become angry over trivial things”) where the responses ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). Cronbach’s α for the current research was .90, and on each dimension of depression, anxiety, and stress it was .85, .93, .83, respectively.

All instruments used in this research had gone through translation and back-translation processes carried out by Indonesian and English experts. The scale used in this study went through 5 stages of adaptation to the scale of Beaton et al. (2000), namely forward translation, synthesis and evaluation of forward translation results, backward translation, synthesis and evaluation of backward translation results, and review of backward translation results.

DATA ANALYSIS

The data underwent a comprehensive examination to assess accuracy, address missing values, identify outliers, verify normality, check for linearity, and evaluate homoscedasticity. Correlations among continuous variables were analyzed using Pearson correlations. The proposed model was then assessed and validated using structural equation modeling (SEM). The research adhered to the two-step approach for SEM as outlined by Kline (2005); initially, the measurement model was tested to ensure a valid measurement of each construct, then the structural model was examined to investigate the relationships among the constructs. This research also provided basic fit indices of confirmatory analysis in addition to information on internal consistency. The fit of the model was determined using the chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic, χ2/df, the comparative fit index (CFI) with values above 0.90 indicating good fit, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values were considered good if they were less than 0.8 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). These indices were used to determine whether the estimated covariance matrix accurately represented the sample covariance matrix. All maximum likelihood estimations for the model were calculated using IBM SPSS AMOS 24.0.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE FINDINGS AND CORRELATIONS AMONG THE VARIABLES

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the assessed variables, while Table 2 presents the correlation matrix among the research variables. The results from the correlation table indicated that resilience negatively correlated with depression, stress, and anxiety but not with FoMO. Conversely, it was also found that FoMO was positively associated with depression, stress, and anxiety.

STRUCTURAL MODEL RESULTS

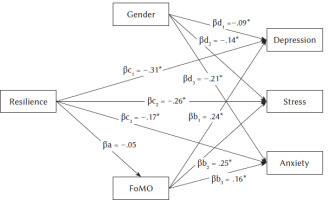

The research hypotheses were tested by conducting SEM on the structural model. The magnitude and significance of the structural path were used to evaluate the hypotheses. First, we tested the Figure 1 model, which fitted reasonably well based on most indices, χ2/df = 8.94, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI [0.04; 0.06].

Figure 1

Structural equation model among variables

Note. FoMO – fear of missing out; *p < .05; βa – standardized beta coefficient between independent variable and mediator; βb – standardized beta coefficient between mediator and dependent variable; βc – standardized beta coefficient between independent variable and dependent variable (direct effect); βd – standardized beta coefficient between gender and dependent variable.

Table 3 displays standardized parameter estimates. The structural model showed that resilience did not significantly predict FoMO. However, resilience significantly and negatively affected depression (β = –.31, p < .001), anxiety (β = –.17, p < .001), and stress (β = –.26, p < .001). Furthermore, FoMO was the strongest predictor for depression (β = .24, p < .001), followed by stress (β = .25, p < .001) and anxiety (β = .16, p < .001).

Table 3

Maximum likelihood estimates of the model

Gender (0 – female; 1 – male) significantly predicted depression (β = –.09, p < .001), anxiety (β = –.21, p < .001), and stress (β = –.14, p < .001). This meant that females were more prone to depression, anxiety, and stress than males. The percentage of variation explained for depression, anxiety, and stress was 15.8%, 15.1%, and 9.5%, respectively.

Based on the mediation results in Figure 1, FoMO did not significantly influence the connection between resilience and depression.

DISCUSSION

The findings indicated that resilience could reduce depression, anxiety, and stress. This discovery aligns with earlier research indicating that young individuals with elevated levels of resilience tend to experience fewer depressive symptoms and exhibit reduced behavioral and emotional issues, while also reporting higher levels of life satisfaction (Kaloeti et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2021; Ziaian et al., 2012). This is because resilience has the potential to lead individuals to enhance their capability (Kobylarczyk & Ogińska-Bulik, 2015). Additionally, it was observed that resilient individuals’ problem-solving contributed to a boost in their positivity (Yildiz, 2017). This confirmed that resilience acted as a protective barrier to prevent depression associated with adverse life events. These findings also have implications for counseling or adolescent support services. Resilience can serve as the foundation for delivering psychoeducation and designing therapeutic interventions, both in group settings and on an individual basis, with the aim of enhancing the mental well-being of adolescents (Gabrielli et al., 2022).

The findings also indicated that individuals who experienced FoMO would be prone to experience depression, stress, and anxiety. This was following previous research which showed a relationship between FoMO and stress, anxiety and depression (Dhir et al., 2018; Elhai et al., 2018). Furthermore, adolescents who exhibited negative emotions often sought an outlet for their feelings by engaging in excessive internet usage, a behavior frequently linked to FoMO condition. This was indicated by Yuan et al.’s (2021) research that FoMO played a pivotal role in mediating the connection between the severity of depression a person experienced and their excessive internet usage.

Interestingly, in this research, resilience did not correlate with FoMO, and FoMO did not play a role in influencing the relationship between resilience and psychological symptoms among adolescents. One possible explanation is that FoMO is a complex construct that measures self-regulation related to one’s desire to stay connected to other people, especially on social media. The measure of resilience taken was the individuals’ ability to adapt to stressful situations experienced in general conditions.

The need to own and the need to be popular among their peers (Beyens et al., 2016) made adolescents perceive connectedness on social media to be crucial without understanding the risk factors in the form of negative experiences that could be experienced in social media interactions. Fascinating discoveries from prior research indicate that the sense of purpose that individuals hold can enhance their psychological well-being, including the significance of social media in the lives of teenagers (Krok & Telka, 2019).

The desire to feel connected to activities carried out by other people in cyberspace was a manifestation of social anxiety and depression that involved unmet social needs (Oberst et al., 2017; Wegmann et al., 2017). This research also showed that depression, anxiety, and stress were more prone to be experienced by girls than boys. This was in line with previous studies (Anyan & Hjemdal, 2016; Saber et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2017; Yue et al., 2015). The condition of females, who were more emotional, found it difficult to regulate and manage negative emotions, and had high sensitivity, made them more prone to experience anxiety than males.

The study had several limitations, which could serve as suggestions for future research. First, the participants in this research were in the young age range. Variation in age range, such as children and adults, would provide a comprehensive picture of the mediating role of FoMO in related variables. Resilience measurements were also carried out on a general sample. Further research can be performed in vulnerable groups. Second, this research did not focus on use of one social media platform, so additional validation of the role of social media popular among age groups, such as Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube, would be beneficial. Third, the data collection was by self-report, so the possible bias in reporting would affect the validity of the data accuracy. Future research might involve other research methodologies, such as interviews and observations. Fourth, this research was completed precisely one month before the implementation of distance learning, so it would be interesting to study the relationship with academic conditions, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when learning took place primarily online.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this research revealed that resilience directly influences the psychological symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety. Individuals who do not have resilience skills will be prone to develop mental health problems. This research also showed that FoMO is a variable that contributes to the emergence of psychological symptoms, especially stress and depression. These findings contribute to the understanding of the impacts of online anxiety-related variables that can generate symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents. This research did not find a relationship between resilience and FoMO, so it is necessary to investigate further the contributing factors, such as personality attributes, to minimize the occurrence of FoMO. Finally, FoMO in this research was not found to mediate the relationship between resilience and psychological symptoms. Therefore, further analysis could explore the role of other broader online behaviors. Research on factors contributing to online behaviors in adolescents can indirectly provide an understanding of ways to increase online resilience.

DISCLOSURE

This work was supported by Penelitian Terapan Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi (PTUPT). Sources of funds: Directorate of Research, Technology and Community Service, Directorate General of Higher Education Research and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, Indonesia, financial year 2022 (grant no. 187-67/UN7.6.1/PP/2022). The authors declare no conflict of interest.