BACKGROUND

MODERN CULTURE AND BODY IMAGE

We live in an epoch marked by a cult of an ideal slender body. At the same time, obesity is regarded as one of the main health problems of the 21st century. The number of people suffering from this disease is constantly increasing and attempts to reduce excess body weight usually fail to bring the desired effect (Rybicka & Szulińska, 2012). Excess body weight is frequently the cause of stigmatization by society (Brytek-Matera & Charzyńska, 2009). This social context can lead to dissatisfaction with one’s appearance and, consequently, a preoccupation with eliminating the discrepancy between the actual and desired figure. Women, for whom excess weight and the build of the lower parts of the body are among the main sources of body dissatisfaction, try to change their appearance at all costs and go on slimming diets (Głębocka & Kulbat, 2005). Kwiatkowska and Skop-Lewandowska’s (2015) study shows the high interest in weight reduction diets among Polish women aged 19 to 39. In more than half of the examined women on a slimming diet there was a yo-yo effect after the diet was over. The most frequent reason for trying to lose weight was low self-esteem and negative body image.

Paul Schilder (1950) coined the term “body image” to refer to the image of our own body we create in our minds – the way our body looks to us. Body image has three components: cognitive, behavioral, and affective. The cognitive component is body-related thoughts. The behavioral component is defined by attitudes towards the body as a whole and towards specific parts of the body. The emotional component comprises all body-related feelings and emotions. Excessive cognitive focus on body image can result in selective attention to information associated with one’s body. Overemphasizing the behavioral component may mean that the individual wants to achieve a perfect figure at all costs through diets, exercise, and other activities aimed at reducing body weight. In the affective domain, wrong body image means that every failure to achieve the desired figure gives rise to dissatisfaction with one’s appearance and negative emotional states (Brytek-Matera, 2010; Rucker & Cash, 1992). The negative evaluation of one’s body often stems from setting oneself high standards in the physical domain and from a desire to meet them all perfectly.

PERFECTIONISM AND BODY IMAGE

According to one of the first definitions of perfectionism, its essence lies in setting unrealistically high standards for oneself, the inability to modify them, and making self-esteem dependent on one’s capability of achieving the standards (Burns, 1980). While early conceptions of perfectionism generally assumed its one-dimensional and negative nature (Ganske & Ashby, 2007), towards the end of the 20th century multidimensional concepts of perfectionism became increasingly popular (Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Shafran et al., 2002). The scholars stressed that perfectionism was a complex construct associated not only with maladaptive but also with adaptive behavior (Stoeber & Otto, 2006). In fact, this kind of approach had been proposed for the first time many years before by Hamachek (1978). Both his conception and Adler’s (1927) theory constitute the theoretical basis for the measure of adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism (Szczucka, 2010) that was used in our research, presented in this paper. In line with this, we assume that maladaptive perfectionism is associated with setting oneself excessively high goals that make it impossible to succeed. Maladaptively perfectionistic individuals are unable to rationally define their capabilities and standards, which is why they often choose goals that are impossible to achieve. If these goals are not accomplished, they focus exclusively on the fact that they have failed. As a result, they experience continual emotional distress. Such people are able to accept themselves only when they achieve full success (Szczucka, 2010). By contrast, adaptive perfectionism refers to a situation in which a person is able to realistically adjust task difficulty to their capabilities. Adaptively perfectionistic individuals want to achieve high goals, but they are guided by rationality and act flexibly. If they fail, they are able to draw conclusions for the future, which enables them to develop (Szczucka, 2010).

Some studies show links between body image and perfectionism. Nigar and Naqvi (2019) found that body areas satisfaction was negatively related to perfectionism, while appearance orientation was positively related to it. This means that with an increase in the level of perfectionism body satisfaction decreases and the focus on one’s appearance increases. Compared to men, the young women taking part in the study were higher in perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, and self-classified weight (i.e., the classification of their body weight in terms of overweight or underweight); they scored lower than men on appearance evaluation and body areas satisfaction. Kantack’s (2014) study on women revealed that higher body image satisfaction was related to lower levels of perfectionism and perfectionistic self-presentation. It was also found that self-esteem was the main predictor of body image satisfaction. Barnett and Sharp (2016) conducted two studies. In the first one, they found that the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and body image satisfaction was mediated by self-compassion. Maladaptive perfectionism was negatively related to self-compassion, which contributes to body satisfaction. As a result, maladaptive perfectionism was associated with lower body satisfaction. The second study conducted on women supported the results of the first study. The self-judgment component of self-compassion was the most important mediator in both studies. This suggests that maladaptive perfectionism influences body image satisfaction through critical self-judgment.

PERFECTIONISM AND SELF-TALK

Shafran et al. (2002) claim that the main factor that maintains maladaptive perfectionism is dichotomous (black-and-white) thinking. Individuals who engage in this type of thinking decide whether or not they have managed to achieve a high private standard in terms of full success or complete failure. For example, if a person trying to slim down has lost four kilograms instead of five as they planned, they will interpret this fact as total failure rather than partial success. Perfectionism combined with a tendency to think in dichotomous terms promotes excessive focus on failures, mistakes, and difficulties in taking action and completing tasks (Lee et al., 2011; Słodka & Skrzypińska, 2016). As a result, maladaptive perfectionists can have lower self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy and a higher level of depression and anxiety symptoms (Chai et al., 2019; Kozłowska & Kuty-Pachecka, 2023; Zeigler-Hill & Terry, 2007). According to Brinthaupt (2019, pp. 3–4), “having anomalous, upsetting, or disturbing self-related experiences should press a person into trying to resolve, understand, or clarify those experiences. Self-talk is one self-regulatory tool that is predicted to be used under these circumstances.” In this context, it seems reasonable to assume that various types of self-talk (ST) are used by maladaptive perfectionists who nearly constantly experience failure in achieving their unrealistic goals.

Self-talk is a multidimensional construct (Latinjak et al., 2023). The literature highlights the wide range of possible functions performed by ST. Mischel et al. (1996) claimed that ST plays a role in inhibiting impulses, guiding courses of actions and monitoring progress toward goals. Carver and Scheier (1998) associated ST with the function of “meta-monitoring” of behavior and goal progression. In this approach, ST can influence emotional reactions and responses to behavioral deficits. Morin (2005) postulated that inner speech plays a key role for self-awareness. In this article, ST is understood as defined by Brinthaupt (2019, p. 2), that is, as self-directed or self-referent speech (silent or aloud) that serves various self-regulatory and other functions.

According to Brinthaupt et al. (2009) ST can be self-reinforcing, self-managing, self-critical, or social-assessing. Self-reinforcing ST refers to a sense of pride in and satisfaction with having done something; it is the least frequent of the four types of ST (Oleś et al., 2020). Self-managing ST applies to general self-regulation and occurs most often (Oleś et al., 2020). It consists in formulating and giving oneself guidelines about what and how to do or say (Brinthaupt et al., 2009). Self-critical ST occurs in situations of failure, expressing discontent, anger, and disapproval directed at oneself for what one has done or said. Finally, social-assessing ST consists in repeating something that someone has said, analyzing other people’s words, and imagining how others will react to what one has said or done. Self-reinforcement and self-management represent more positive aspects of ST, whereas social assessment and self-criticism seem to represent more negative aspects. For example, research showed that self-esteem was negatively associated with social-assessing and self-critical ST and positively associated with self-reinforcing ST. Self-managing ST and self-esteem were not interrelated (Brinthaupt et al., 2009).

THE CURRENT STUDY

In line with Brinthaupt’s (2019) assumptions, it can be expected that in maladaptive perfectionists trying to slim down, failures to achieve goals, such as a one-time broken diet, will result in the appearance of various types of ST. Given that there is a positive link between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image (Barnett & Sharp, 2016; Kantack, 2014; Nigar & Naqvi, 2019), the question arises as to whether different types of ST mediate this relationship. Answering this question was the aim of our study, which was conducted on a sample of overweight or obese women who expressed dissatisfaction with their body while undertaking weight loss.

We hypothesized that self-reinforcing ST, self-critical ST, and social-assessing ST act as parallel mediators in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image. The associations of maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image with self-reinforcing ST will be negative, whereas the associations of these two variables with self-critical ST and social-assessing ST will be positive.

The justification for our hypothesis was based on the following reasoning. Maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image are positively related (Barnett & Sharp, 2016; Kantack, 2014; Nigar & Naqvi, 2019). High maladaptive perfectionism combined with dichotomous thinking contributed to excessive focus on failures (Słodka & Skrzypińska, 2016). Any failure to keep a diet or weight loss smaller than expected will be treated by perfectionists not so much as partial success for which they should appreciate themselves but as a complete failure to achieve the goal, which may lead to the blocking of self-reinforcing ST and an increase in self-critical ST (Brinthaupt et al., 2009). Maladaptive perfectionism also manifests itself in a sense of pressure from others to be perfect (Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Therefore, among overweight or obese people trying to lose weight and exhibiting maladaptive perfectionism, a fear of criticism from others will probably favor the use of social-assessing ST, associated with other people’s opinions (Brinthaupt et al., 2009). In this context, maladaptive perfectionism is expected to be negatively associated with self-reinforcing ST, and positively associated with self-critical and social-assessing ST. On the other hand, negative body image depends on criticism from others and a fear of social assessment (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2002). Body dissatisfaction (Brytek-Matera, 2010; Kantack, 2014), similarly to maladaptive perfectionism (Chai et al., 2019; Zeigler-Hill & Terry, 2007), is also related to lowered self-esteem. Low self-esteem is in turn accompanied by self-critical and social-assessing ST, whereas the correlation between self-reinforcing ST and self-esteem is positive (Brinthaupt et al., 2009).

Since Brinthaupt et al. (2009) found that self-managing ST was not related to self-esteem, we expected that this ST type would not correlate with maladaptive perfectionism and, as a result, it would not mediate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image. Therefore, we did not include self-managing ST in our hypothesis.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were selected through purposive sampling – we were looking for overweight or obese women who were currently losing weight. The women were also asked about their weight and height, so that we could determine their BMI and decide if they really had overweight or obesity. A total of 266 women entered the study, but 17 of them were not trying to slim down, 19 did not have overweight or obesity, and 16 did not complete the survey in a reliable manner (missing data). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 214 women with overweight or obesity in the process of losing weight. The mean duration of the process of losing weight was 16.86 months. Participants’ age ranged from 20 to 58 years (M = 32.91, SD = 6.96). Demographic characteristics of respondents are presented in the Supplementary materials.

PROCEDURE

Data were collected through a web survey; links to the survey were posted on social networks (Facebook, Instagram) and online forums. Respondents were informed that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. The procedure was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the first author’s university (approval number KEBN_5/2023).

MEASURES

The web survey consisted of three measures. Their internal consistency determined in this study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Internal consistency coefficients and Pearson’s r correlations between the analyzed variables

The Body Attitude Test (BAT). This questionnaire was developed by Probst et al. (1995). We used the Polish version of the BAT (Brytek-Matera & Probst, 2014), which consists of 20 items, divided into three factorial subscales: (1) BAT-1 measures negative appreciation of body size (7 items); (2) BAT-2 measures lack of familiarity with one’s own body (7 items); (3) BAT-3 measures general body dissatisfaction (4 items). Respondents rate each item on a 6-point scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The BAT was designed to be completed by women. The higher the score is, the more negative is the respondents’ body experience (Brytek-Matera & Probst, 2014).

The Self-Talk Scale (STS). This questionnaire was developed by Brinthaupt et al. (2009). We used the Polish version of the measure (Oleś et al., 2023). The STS has four subscales, corresponding to the four functions of ST: self-reinforcement, self-criticism, social assessment, and self-management. The meaning of each subscale has been explained in the Background. The STS consists of 16 items, 4 items per subscale. Respondents indicate their ratings on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The higher the score is, the higher is the level of a given type of ST (Brinthaupt et al., 2009).

The Polish Adaptive and Maladaptive Perfectionism Questionnaire. The scale was developed by Szczucka (2010). It is used to measure two dimensions of perfectionism: adaptive and maladaptive. Its theoretical basis was Adler’s (1927) and Hamachek’s (1978) theories. The questionnaire consists of 35 items, divided into two subscales. The adaptive perfectionism (AP) scale consists of 13 items, and the maladaptive perfectionism (MP) scale consists of 22 items. The meaning of each subscale has been explained in the Background. Respondents answer using a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The higher the score is, the higher is the level of a given type of perfectionism.

RESULTS

Prior to the main analyses, we calculated descriptive statistics and tested the assumptions of normality. Using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction, we found that only the scores on maladaptive perfectionism and BAT-2 met these assumptions. Therefore, in the next step, we analyzed skewness. BAT-2, self-criticism, social assessment, and self-reinforcement were slightly positively skewed (from 0.03 to 0.36), while adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism, self-management, BAT, BAT-1, and BAT-3 were slightly negatively skewed (from −0.13 to −0.29). All skewness coefficients were in the −1 to 1 range, which means skewness was not strong enough to require further attention and could be ignored (George & Mallery, 2010).

Next, we computed Pearson’s bivariate correlations for all the variables measured in the study (see Table 1). It turned out that negative body image (BAT) did not correlate with adaptive perfectionism, whereas the correlation between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image was positive and strong. The same relationship was observed in the case of the three subscales measuring body image. Negative appreciation of body size (BAT-1), lack of familiarity with one’s own body (BAT-2), and general body dissatisfaction (BAT-3) were positively related to maladaptive perfectionism. This means that a woman who does not accept her body (BAT-1) is unable to realistically specify its size (BAT-2), and shows general dissatisfaction with what she looks like (BAT-3), more often strives for perfection while at the same time focusing on her failures and showing a fear of failure.

Maladaptive perfectionism, similarly to negative body image, correlated moderately negatively with self-reinforcing ST and moderately positively with self-critical and social-assessing ST. Weak positive correlations of these two variables with self-managing ST were also found. Adaptive perfectionism did not correlate with any other variables.

Our hypothesis was tested using mediation analysis. We used the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018). Completely standardized indirect effects were calculated for each of the 5,000 bootstrapped samples, and 95% confidence intervals were computed.

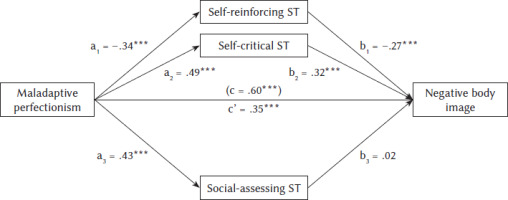

We hypothesized that three types of ST would act as parallel mediators in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image. The results of the analysis are presented in Figure 1. Using Monte Carlo simulation (Schoemann et al., 2023), the post-hoc power of the tests was estimated. Given our sample size (N = 214) and the effect sizes actually obtained, it was as follows: for the a1b1 path = 1.00, for a2b2 = 0.99, for a3b3 = 0.92 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Types of self-talk (ST) as parallel mediators between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image

Note. ***p ≤ .001; a, b, c, c’ – tested paths.

Our hypothesis was partially supported. It turned out that self-reinforcing ST and self-critical ST mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image. The indirect effect of self-reinforcing ST on negative body image was statistically significant and positive: IE = 0.09, 95% CI [0.04; 0.16]. This means that, as maladaptive perfectionism increases, there is a decrease in self-reinforcing ST, which is accompanied by an increase in negative body image. The indirect effect of self-critical ST on negative body image also turned out to be statistically significant and positive: IE = 0.15, 95% CI [0.07; 0.25]. This means that an increase in maladaptive perfectionism is accompanied by an intensification of self-critical ST, which contributes to an increase in negative body image. Contrary to our hypothesis, the indirect effect of social-assessing ST on negative body image proved to be statistically non-significant: IE = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.06; 0.06].

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to determine what relationships there were between body image, perfectionism, and different types of ST among women with overweight or obesity who expressed their body dissatisfaction while undertaking weight loss. We hypothesized that the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image was mediated by self-reinforcing, self-critical, and social-assessing ST. The types of ST that proved to be parallel mediators were self-critical ST and self-reinforcing ST. This means that maladaptive perfectionism favors self-critical ST, which results in negative body image. At the same time, leading to a focus on failures and weaknesses, maladaptive perfectionism decreases the chance of self-reinforcing ST, which could prevent the development of negative body image. These results seem to be in line with those reported by Barnett and Sharp (2016). These authors analyzed maladaptive perfectionism, operationalized as the discrepancy between an individual’s high standards and his or her actual achievements (Slaney et al., 2001), and the relationship of this perfectionism to body image satisfaction. They found that this relationship was mediated by self-compassion, particularly by one of its components – namely, self-judgment. It was thus established that maladaptive perfectionism influenced body image satisfaction through critical self-judgment. In our study, emphasis is also placed on critical self-judgment, expressed as ST in this case. Additionally, our study revealed another mechanism, consisting in the reduction of self-reinforcing ST, being the kind of ST that could build a more positive body image.

The most surprising finding of our study is the fact that, contrary to the hypothesis, social-assessing ST was not a mediator between maladaptive perfectionism and negative body image. Many authors underscore the role of social assessment in the development of negative body image (Brytek-Matera & Charzyńska, 2009; Cash & Pruzinsky, 2002). Although our study indicated that maladaptive perfectionism was associated with social-assessing ST, this type of ST had no significant effect on negative body image. This result, if replicated, could be of great importance to psychological practice. The unfavorable assessment of our body by others will not be a source of our negative body image as long as we do not begin to criticize ourselves and block praise directed at ourselves.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The present study has certain practical implications for prevention and intervention activities aimed at building positive body image. The knowledge that maladaptive perfectionism is associated with negative body image is no longer new. It is used by therapists, who try to reduce their patients’ perfectionistic behaviors in order to help them develop a more favorable attitude towards their own imperfect bodies. It is worth noting, however, that ST seems to be a relatively easily modifiable phenomenon. Therefore, minimizing self-critical ST and replacing it with self-reinforcing ST in therapeutic work aimed at changing body image into a more positive one may prove to be a new and highly promising path.

LIMITATIONS

The present study has some limitations as well. First, the measures we used were based on self-reports, and response bias could not be controlled. It should be noted, however, that some phenomena, such as ST, must be investigated on a self-report basis because they cannot be observed by others. Taking this into account, in future research it is advisable to go beyond questionnaires and include qualitative data in the analyses. Second, our study has a weakness associated with the interpretation of mediation analyses. We are aware that we have sometimes suggested a cause-and-effect pattern on the basis of cross-sectional data, but it should be remembered that causal relationships can be established only based on longitudinal or experimental studies. Third, the presented results require replication, since this was the first study into the relationships between body image, perfectionism, and different types of ST to be conducted in a particular group – that is, among women with overweight or obesity setting out to lose weight. It is known, however, that slimming down concerns not only women with overweight and obesity and that the problem of people rejecting their own body is increasingly widespread. In this context, what would be particularly desirable is extensive research on women and men, including adolescents, who objectively do not have problems with excess weight. It would also be advisable to conduct research using a longitudinal design, examining how training in the use of self-reinforcing ST modifies body image.

Supplementary materials are available at the journal’s website.