BACKGROUND

One of the basic functions of the media is to notice significant changes in reality and inform the public about them (McQuail, 2010). In times of uncertainty and crisis, people most often turn to the media for information and, thus, use them more frequently (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). In March 2020, World Health Organization announced the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) breakout as a pandemic, which brought about severe distress. The distress arose as a consequence of the spread of the virus and related risk of loss of health or life, as well as the outcome of lockdown introduction – worries about losing a job, deteriorating economic conditions, and limiting social contacts. In the initial phase of the pandemic, news media provided instant information concerning public health, for example, the latest recommendations given by the WHO (Anwar et al., 2020).

Most of the research to date on the effects of exposure to news has focused on media during dramatic events, such as terrorist attacks (Neria et al., 2011; Schlenger et al., 2002) or wars (Israeli conflict: Bodas et al., 2015; Iraq war: Silver et al., 2013). Few studies have analyzed the effects of exposure to news media in public health crises. They concerned threats related to the Ebola virus in the US (Thompson et al., 2017), the H1N1 influenza pandemic in the US and Mexico (McCauley et al., 2013), and, recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. The research conducted since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has indicated the occurrence of negative effects of exposure to news media, such as elevated distress (Stainback et al., 2020), fear and anxiety (Sasaki et al., 2020), and depressive symptoms (Olagoke et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2020). However, a few researchers suggest that exposure to news media during the COVID-19 pandemic may have some positive effects and be a way to deal with a difficult situation (Eden et al., 2020). Previous research also showed that gender may differentiate the effects of exposure to news media (Marin et al., 2012; Schlenger et al., 2002).

Considering the fact that the research of our predecessors focused mainly on the analysis of the negative effects of exposure to news media during dramatic events and crises, we analyzed both negative and positive effects of exposure to news in our study.

The present study aimed to answer three questions. First, we analyzed whether the use of news media in the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with life satisfaction and, if yes, what the nature of the association is. Second, we checked whether exposure to news media is associated with COVID-19-related fear and worries and whether COVID-19-related fear and worries mediate the relation between exposure to news media and life satisfaction. Third, we examined whether gender differentiates the effect of exposure to news media in a health crisis – the COVID-19 pandemic.

NEWS MEDIA EXPOSURE AS A WAY TO COPE WITH DISTRESS IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The available research on the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for well-being indicates that the pandemic is associated with elevated distress (Zhao et al., 2021). According to the cognitive-transactional concept of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), coping with stress involves “cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). The purpose of performing such actions is to increase the well-being of an individual that has been disrupted as a result of contact with a stressor. Previous research revealed that using media in times of crisis may be a coping method (Eden et al., 2020). In addition, available findings show that people who have problems concerning a particular area of life spend more time reading information that they find helpful in coping in such critical situations than reading other information (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2009).

Media users exposed to COVID-19 information may deal with stress using problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, or avoidance strategies, less effective from a long-term perspective (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2009). Individuals taking a problem-focused approach use media to look for guidelines and tips on how to behave to maintain health and avoid negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (Eden et al., 2020; Melki et al., 2022). Obtaining information leads to reducing uncertainty, especially if the situation is not like anything experienced before or when other sources of information are inaccessible (Peters et al., 2017). Individuals adopting an emotion-focused approach become aware, thanks to information from the media, that other people face similar challenges and, therefore, interpret their situation more positively (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2009). The use of avoidance strategies means denying the fact that the situation is difficult. When the level of experienced stress is high, avoidance strategies involving denial of news about an existing threat or risk may occur (Lazarus, 1991). An extreme case of following an avoidance strategy is quitting the use of news media. However, statistical data show that media news consumption in the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic soared, which may indicate a weak tendency to use avoidance strategies during that period (Nielsen, 2020).

In times of crisis, the use of news media can be a way of coping with stress by interpreting and distorting obtained information so that one could perceive oneself and one’s life more positively (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2009). For example, as media are the sources of standards for social comparisons with others (Buunk & Gibbons, 1997), individuals can observe, through media, other disadvantaged people and feel better by making downward comparisons with them (Mares & Cantor, 1992). Researchers hold that downward comparisons elicit such pleasant emotions as a sense of pride, satisfaction with one’s life situation, or so-called schadenfreude – a feeling of joy from harm or misfortune suffered by another (Lewis & Weaver, 2016). During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, media provided information that triggered a tendency to make comparisons in various areas of life: health, interpersonal relationships, or career development. The earliest studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that social comparisons on social media may lead to elevated life satisfaction – both by treating the information as a reference point for assessing one’s life situation and by creating a unity of common experiences and sharing painful emotions (Ruggieri et al., 2021). Some studies carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic have also revealed the occurrence of the “unrealistic optimism” effect (Doliński et al., 2020), which is holding a belief that one is less likely to go through negative experiences than others. Thus, while observing a negative situation, reported in the media, that affects other people, one may create positive illusions about one’s chances of contracting the disease, which, in turn, may be positively related to life satisfaction. Therefore, considering the findings discussed above, we formed the following hypothesis: H1: news media exposure will be positively related to life satisfaction.

NEWS MEDIA EXPOSURE AND COVID-19-RELATED FEAR AND WORRIES

In general, the majority of media coverage – not only during the COVID-19 pandemic – is neither neutral nor positive, and abounds in drama and negativity. The media direct the audience’s attention to crime, terrorist attacks, wars, or natural disasters, and also report relatively neutral events in a negative tone (Boukes & Vliegenthart, 2017). Journalists describe this rule as “bad news is good news” or “if it bleeds it leads” (Johnson, 1996), and psychologists use the term “negativity bias”, as it is common knowledge that negative news better attracts recipients’ attention and is better remembered by them (Baumgartner & Wirth, 2012; Zillman et al., 2004). With the development of technology and media, the frequency of exposure to negative information has increased and, as a consequence, several negative psychological problems have been observed, such as elevated stress and negative emotions (Boukes & Vliegenthart, 2017). The fact that reading and watching the news in the media may produce negative effects has been proved by many experimental and correlational studies (Balzarotti & Cicero, 2014; de Hoog & Verboon, 2020; Johnston & Davey, 1997). These also include research done during and after dramatic events, such as terrorist attacks (e.g., the Boston Marathon bombing; Holman et al., 2014) or mass shootings (e.g. the Copenhagen shooting; Boukes & Vliegenthart, 2017). Extensive research into the effects of exposure to negative information was also conducted after the attack on the World Trade Center (see Neria et al., 2011). It demonstrated that the frequency of watching television in connection with the September 11 attacks was associated with stress occurrence in viewers (measured on two consecutive days following the event: Schuster et al., 2001, and a few years afterward: Silver et al., 2013), and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Schlenger et al., 2002). Other studies have also shown that repeated and prolonged exposure to news about a health crisis may lead to elevated fear and worries (post-Ebola studies in the US: Thompson et al., 2017, or studies during the H1N1 pandemic: McCauley et al., 2013).

In the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic, people were exposed to media coverage that reported potential threats (e.g., the spread of the disease and the number of deaths, which triggered thoughts about one’s mortality and the loss of loved ones) and deprivation (e.g., a possibility of losing a job or deterioration of economic conditions and social isolation – loss of social contacts). This could lead to negative outcomes, such as COVID-19-related fear, which concerns fear for physical health and safety, and COVID-19-related worries, which refers to the feeling of insecurity about what the future will bring and how everyday functioning will change, for example in the field of work, social contacts or self-development.

Fear and worries are fueled by a situation that is unpredictable and beyond personal control (de Hoog & Verboon, 2020). The first correlational studies carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that exposure to news media may lead to distress (Stainback et al., 2020), fear and anxiety (Sasaki et al., 2020) and depressive symptoms (Olagoke et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2020). Also, one diary study showed that participants reported more COVID-19-related worries on days with higher exposure to COVID-19-related media (Schmidt et al., 2022). Therefore, taking account of the above-described reports, we formulated the following hypothesis: H2: news media exposure will be positively related to COVID-19 fear (H2a) and COVID-19 worries (H2b).

COVID-19-RELATED FEAR AND WORRIES, LIFE SATISFACTION, AND GENDER

The emergence of a new disease associated with SARS-CoV-2 has not only increased stress among the worldwide population but has also radically changed the way societies function in many areas of life. Fear and worries are a natural response to a threat that may mobilize a person to act, but in excess, it may significantly reduce life satisfaction, which has been confirmed by many studies (Dymecka et al., 2021; Fardin, 2020). Therefore, in line with the results of the studies presented above, we proposed the following hypothesis: H3: COVID-19 fear (H3a) and COVID-19 worries (H3b) will be negatively related to life satisfaction.

Previous studies indicated that women experience fear and anxiety more frequently and more intensely (McLean & Anderson, 2009). The latest findings have shown that, compared to men, women experience higher levels of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kowal et al., 2020). However, during the pandemic, an increase in anxiety, fear, and depression was also reported in men (Twenge et al., 2021). Women and men experience fear and anxiety related to COVID-19 differently. As shown by research on the content of social media posts, women are mainly worried about their loved ones and, therefore, express more negative emotions, such as anxiety and fear, while men are worried about the far-reaching social and economic impacts of the pandemic (van der Vegt & Kleinberg, 2020). Furthermore, similar differences were found in studies on the response to negative news via media. Negative effects of exposure to news about the attack on the World Trade Center were more common in women than in men (Schlenger et al., 2002). Studies using physiological measurements (cortisol levels in saliva) demonstrated that viewing negative information significantly increases physiological reactivity to other stressors, which turns out to be characteristic only of women, and which was not observed in the group of men and women exposed to neutral news. Moreover, the same study revealed that women remember negative information better than men (Marin et al., 2012).

In conclusion, research so far indicates, first, that COVID-19-related fear and worries are negatively associated with life satisfaction (Dymecka et al., 2021; Fardin, 2020) and that exposure to news in times of crisis may cause fear and anxiety (Balzarotti & Cicero, 2014; Boukes & Vliegenthart, 2017; Holman et al., 2014; Johnston & Davey, 1997). Second, women experience fear and anxiety more intensely and experience these in a different way than men (Kowal et al., 2020; van der Vegt & Kleinberg, 2020). Therefore, allowing for the reports above, we put forward the following hypothesis: H4: there is an indirect effect of news media exposure on life satisfaction via COVID-19 fear (H4a) and COVID-19 worries (H4b) moderated by gender. Higher COVID-19 fear and worries will decrease the positive association between exposure to news and life satisfaction, and this effect will be stronger in women.

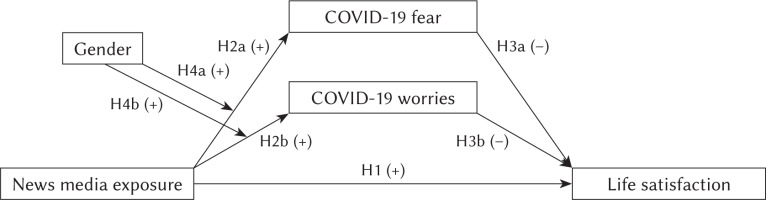

To check the hypotheses constructed in our study, we tested a moderated mediation model, where COVID-19 fear (a) and COVID-19 worries (b) mediate the relation between news media exposure and life satisfaction, with gender moderating the relation between news media exposure and COVID-19 fear and COVID-19 worries (see Figure 1).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

A sample of 371 people was examined, including 264 women and 105 men (two people marked the “other” option) aged 19 to 65 (M = 28.88, SD = 10.25). The largest group was within the age range of 19-29 (240), while far fewer were in the age range of 30-39 (71), 40-49 (40), 50-59 (15) and 60-65 (5). 193 participants identified themselves as students while 176 participants identified themselves as employees. The respondents had vocational (1%), secondary (48.2%), and higher (51.5%) education. The majority of the respondents lived in towns with a population of over 100 000 (58.5%), and the others lived both in towns with a population between 20 000 and 100 000 (19.9%) and in towns with a population of under 20 000 inhabitants (21.6%). The participants assessed their material status as satisfactory (M = 6.34, SD = 1.72 on a 9-point scale).

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted in the initial phase of the pandemic, during the total lockdown in Poland from April 1st to June 6th, 2020. All required ethical standards were maintained while carrying out the study, which was anonymous and voluntary. The study was conducted via an online platform. A hyperlink to the questionnaire was shared on the university subpages and profiles on social media. Students of full-time, part-time, and postgraduate courses were asked to fill in the questionnaire and pass the invitation to participate in the study to their fellow friends. Respondents completed a set of scales including a news media exposure scale, a COVID-19-related fear and worries scale, a life satisfaction scale, metrics, and several questions irrelevant to the purpose of this research.

MEASURES

Measurement of news media exposure. A specially designed questionnaire was used to measure exposure to news media. It was an inventory of the 15 most popular opinion-forming television, radio, press, and online news media based on the indicators of respective media use frequency (CBOS, 2019; IMM, 2020). The inventory includes both public and private, nationwide TV stations (e.g., TVP Info, TVN 24), radio stations (e.g., RMF FM, Radio Zet), daily newspapers (e.g., “Gazeta Wyborcza”, “Rzeczpospolita”), and news portals (e.g., wp.pl, interia.pl), and local media, in general. The respondents used a 5-point scale from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often) to rate how often they used each of the given news media to obtain information within the last 3 weeks.

Measurement of COVID-19 fear and worries. A questionnaire inspired by a measurement tool applied by other researchers was used to measure COVID-19-related fear and worries (Kroencke et al., 2020). The COVID-19-related fear and worries scale consists of two subscales. The COVID-19-related fear subscale includes 3 statements concerning health and safety (e.g., “I am anxious about my health”; “I am anxious about my safety”; “I am anxious about the health of people I care about”). The COVID-19-related worries subscale includes 5 items concerning the feeling of insecurity and fear of change (“I think my life will change for the worse due to the pandemic”; “I am worried about my future and that of my loved ones”; “I believe that the financial situation of me and my family will deteriorate significantly”; “I believe that our country will face serious economic consequences”; “I think I will not be able to pursue my passions and interests”). Respondents rated the statements on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of the tool was acceptable (Cronbach’s α for COVID-19-related fear = .78, for COVID-19-related worries = .67).

Measurement of life satisfaction. A life satisfaction scale consisting of partial satisfaction measurements was used (Czapiński & Panek, 2015). This tool includes a set of statements about satisfaction in various spheres of life: work or education, relationships with others, material status, and health and life, in general. Respondents rated the statements on a 9-point scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 9 (very satisfied). The level of reliability for this tool was satisfactory (α = .78). Overall life satisfaction was the mean of the respondents’ answers.

RESULTS

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

We tested the moderated mediation model (Model 7) using the Process macro (Hayes, 2013). We examined the indirect effects with bias-corrected bootstrapping (n = 5000) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the indices.

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

The results of preliminary correlation analyses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and correlations between tested variables

The results indicated a significant positive relationship between exposure to news media and life satisfaction, and a significant negative relation between COVID-19 fear and COVID-19 worries, and life satisfaction. Gender showed no significant relation with life satisfaction but it did with COVID-19 fear and COVID-19 worries: COVID-19 fear was associated with the female gender while COVID-19 worries were associated with the male gender.

NEWS MEDIA EXPOSURE, COVID-19 FEAR, GENDER, AND LIFE SATISFACTION

To check our hypotheses H1, H2a, H3a, and H4a, we analyzed two regression models: a moderator variable model predicting COVID-19 fear, and a dependent variable model predicting life satisfaction (see Table 2).

Table 2

Gender as a moderator and COVID-19 fear as a mediator in the relation between news media exposure and life satisfaction

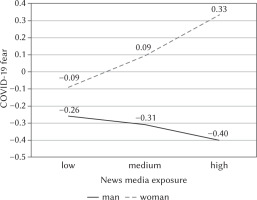

The moderator variable model showed that there is a significant negative relation between COVID-19 fear and exposure to news media: coeff. = –.38, SE = .18, t = –2.05, p = .041, LLCI = –.740, ULCI = –.016 (H2a unconfirmed). The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed a significant moderated mediation effect: coeff. = .30, SE = .11, t = 2.84, p = .005, LLCI = .093, ULCI = .510, in which gender moderated the mediating effect of COVID-19 fear on the relation between exposure to news media and life satisfaction (see Figure 2). The indirect effect of news exposure on life satisfaction was statistically significant for female respondents, but was not significant for male respondents (coeff. = .46, SE = .11, t = 4.15, p < .001, boots LLCI = .242, boots ULCI = .678). The moderation mediation effect for COVID-19 fear was confirmed for women (H4a).

The dependent variable model predicting life satisfaction was found to be significant and indicated that both exposure to news media (coeff. = .20, SE = .05, t = 3.83, p < .001, boots LLCI = .095, boots ULCI = .297) and the level of COVID-19 fear (coeff. = –.14, SE = .05, t = –2.79, p = .006, boots LLCI = –.245, boots ULCI = –.042) were significantly related to life satisfaction. High news exposure was linked to higher life satisfaction, and elevated COVID-19 fear was linked to lower life satisfaction. Thus, the obtained results also confirmed hypotheses H1 and H3a for COVID-19 fear.

NEWS MEDIA EXPOSURE, COVID-19 WORRIES, GENDER, AND LIFE SATISFACTION

To verify hypotheses H1, H2b, H3b, and H4b, we tested the moderated mediation effect of gender and COVID-19 worries on the relation between exposure to news media and life satisfaction. We analyzed two regression models: a moderator variable model predicting COVID-19 worries, and a dependent variable model predicting life satisfaction (see Table 3).

Table 3

Gender as a moderator and COVID-19 worries as a mediator in the relation between news media exposure and life satisfaction

The effect in the moderator variable model predicting the exposure to news media for COVID-19 worries was statistically nonsignificant: coeff. = .25, SE = .19, t = 1.29, p = .198, LLCI = –.129, ULCI = .619 (H2b unconfirmed). The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the moderated meditation effect was nonsignificant: coeff. = –.11, SE = .11, t = –1.02, p = .310, LLCI = –.327, ULCI = .104. The moderated mediation effect of gender for COVID-19 worries (H4b) was not supported.

The dependent variable model predicting life satisfaction was significant and indicated that exposure to news media (coeff. = .19, SE = .05, t = 3.88, p < .001, boots LLCI = .095, boots ULCI = .291) and the level of COVID-19 worries (coeff. = –.25, SE =.05, t = –5.03, p < .001, boots LLCI = –.349, boots ULCI = –.153) were significantly related to life satisfaction. As in the case of the model with the COVID-19 fear mediator, high news media exposure was linked to higher life satisfaction, and elevated COVID-19 worries were linked to lower life satisfaction. Thus, the obtained results confirmed hypotheses H1 and H3b for COVID-19 worries.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the relations between exposure to news media, COVID-19 fear and worries, and life satisfaction, and also sought to determine whether this relation depends on the gender of media users.

We confirmed that fear and worries related to COVID-19 are negatively associated with life satisfaction. The obtained result verifies previous research, which found that fear and worries related to a health crisis reduce life satisfaction (Dymecka et al., 2021; Fardin, 2020).

As regards media usage, it was found – in line with the assumptions made in the study – that exposure to news media is positively associated with life satisfaction. The results obtained here support other research indicating positive effects of exposure to news media during a health crisis (Eden et al., 2020), showing that media exposure is associated with a positive evaluation of one’s life, which was particularly evident at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and may thus be a means of coping with a crisis. In line with this result but opposite to the assumptions, media exposure negatively predicted the COVID-19 fear, and there was no significant relationship between media exposure and COVID-19 worries. It suggests that usage of media might help in coping with the anxiety about one’s health and safety as at this point of the pandemic media provided information about preventive behaviors referring to avoiding infection but they presented no solutions to upcoming economic or social worries.

However, in accordance with the assumptions, gender was found to play a role in predicting the relation between news media exposure and the level of COVID-19 fear. An effect of gender interaction and COVID-19 fear in the relation between exposure to news media and life satisfaction was observed, which means that exposure to news in women may increase COVID-19 fear and, in turn, lower life satisfaction. The effects observed for gender are comparable to other available research, which showed that women experience higher levels of stress in the COVID-19 pandemic than men (Kowal et al., 2020) and that women are more susceptible to experiencing fear for the health and life of their loved ones than men during a health crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (van der Vegt & Kleinberg, 2020). The results indicating gender differences can also be interpreted along the lines of the social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012), according to which women and men have different social roles to fulfill, and men may be less likely to admit fear so as not to lose face (Melki et al., 2022).

No significant relations were observed regarding the effect of moderated mediation in the case of worries related to COVID-19, and no statistically significant relation was found between exposure to news media and COVID-19 worries. Looking for an explanation for the absence of the expected effects concerning COVID-19 worries, we may refer to the conclusions of previous studies on the effects of exposure to media conducted in the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic. They demonstrated consistently a significant relation between exposure to news media and fear, and related symptoms of depression (Olagoke et al., 2020; Sasaki et al., 2020). Only a few studies have shown that media exposure is associated with increased concerns about future economic problems and losing a job in the event of a health crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and this applies to men (van der Vegt & Kleinberg, 2020).

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

A limitation of the study is that it was carried out through an internet platform, which makes it likely that the questionnaire was sent out only to a specific group of respondents – social media users. Therefore, in the future, the sample should be extended to include a varied selection of individuals. Also, women participating in the study considerably outnumbered men. A further study should re-examine gender effects with an equal number of both. In subsequent studies, it is also worth taking into consideration the subjects’ possession of children, as it appears that parents experience higher levels of stress than those without children (APA, 2020), and there is also evidence that psychological and parental stress levels increased during the pandemic (Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, in future studies, it is worth considering exploring the moderating effect of personality traits, as some of them have been found to be associated with fear of COVID-19, such as emotional stability or extraversion (e.g., Łoś et al., 2022; Oniszczenko & Turek, 2022).

Another limitation is the fact that the study analyzed data including representatives of a single culture only. Furthermore, given that the study was carried out in Poland, a Central European country, whose population tends to exhibit a high level of uncertainty avoidance (uncertainty tolerance – 93; Hofstede Insights, n.d.), obtaining information from the media can be a way to avoid uncertainty (Kim et al., 2020). Future studies should extend the sample and be conducted in other countries and cultures, which have lower levels of uncertainty avoidance to check if news media exposure will have similar positive effects in these countries.

The present study was conducted in the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the interpretation of its conclusions should refer to this period only. In a novel and threatening situation, people tend to look for information in a compulsive way to overcome their anxiety (Salvi et al., 2021). During a health crisis supplementary research that uses longitudinal studies and measures media use on a daily basis over a longer period of time should be done to check how news media use is related to fear and worries about the health crisis and life satisfaction.

The answer to the question of why people who use news media more frequently in the initial period of a health crisis evaluate their lives more positively is manifold. Therefore, further studies should consider possible correlates of this relation, such as strategies of coping with stress, a tendency towards social comparisons, a level of unrealistic optimism, or the type of information presented in the media.

Finally, some effect sizes obtained in this study are small to moderate, which means caution is needed when interpreting the results. However, in media research, small and medium effects are common (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings indicate the need to research psychological resources to cope with fear and worries in a health crisis. Long-term stress and negative emotions may cause inappropriate health and help-seeking behavior and, at the same time, lead to overloaded medical facilities and, eventually, to a collapse of the health system (Garfin et al., 2020). One of the resources, according to available research, might be the use of news media providing information about programs and initiatives to support mental health in a health crisis, addressed especially to people at risk of increased anxiety (Brooks et al., 2020).

The present study expands our understanding of the role that news media can play in shaping the user’s well-being in a time of a health crisis. It demonstrates that the effects of exposure to news media during a crisis are twofold. On the one hand, the use of news media is associated with a more positive evaluation of one’s life, which may indicate that media use is a way to cope with a crisis. On the other hand, frequent use of news media leads to an elevated level of anxiety related to COVID-19, which, in turn, lowers women’s well-being.

The results of the present study provide editors of news media with factual information regarding the importance of responsible selection and presentation of news since it may influence the perception of reality by its recipients and, consequently, shape their behaviors, including pro-health behaviors. Editorial offices should also consider the differences between users (e.g., gender), as their characteristics, needs, and motivations are related to different responses to news media.

The role of editors and journalists is not only related to the responsibility for the user’s mental health but it is also related to the adoption of an appropriate business model, for example, avoiding a situation in which users abandon a media outlet because long-term use may result in reduced well-being. Many editorial offices noticed the problem and, following WHO (2021) guidelines, in later stages of the pandemic tried not to promote or display negative news on the front pages or main pages of their editions.