BACKGROUND

Across Europe women are staying longer in the workforce. Women’s labour force participation reached a record level of 66% in 2022, with the largest increases observed in the 55-64 years old age group (OECD, 2023). In the United Kingdom, women are disproportionately affected by pension changes and are working for longer, extending their working life, often in lower paid and part time roles, compared to men. The most predominant sectors occupied by women are health and social work (21% and 77% of all jobs are held by women in this sector), followed by wholesale and retail sectors (13%), then the education sector (12% and 70% of all jobs are held by women in this sector) (Office for National Statistics [ONS], 2022).

ONS (2022) data show that women in the 55-64 years old group have the highest levels of sickness absence, with absence due to stress being most likely in this group (ONS, 2022). In the UK, women’s pension age has been harmonised, and research demonstrates that women extend their working life more than men and are disproportionately affected by inequalities, including health inequalities, over the course of their lives (Finch, 2014). Stress accumulation over the life course has been demonstrated to affect older women disproportionately in relation to impacts on wellbeing, cognition and health (Miller et al., 2022).

THE INTERSECTION OF AGE AND GENDER

The intersection of age and gender has been previously explored, and a range of negative perceptions around women have been highlighted, but these studies have not focussed on UK women and the intersection of women aged 60 facing extending their working lives and in lower-paid positions (Berger, 2021; Bowman et al., 2017; Westwood, 2023). Bowman et al. (2017) illuminated the voices of women in work in Canada and highlighted that older women in work are at risk of being perceived as ‘rusty’ and ‘invisible’, and this was emphasized with respect to the intersection of gender and age in that ‘lookism’ is combined with ‘ageism’. Gendered ageism has been dubbed ‘sexageism’, with invisibility often experienced by ageing women. This can vary according to status, with those in lower status roles being impacted most negatively due to the lack of power that comes with ageing as ‘performance’ whereby the objective is to hide the deteriorations perceived to occur with ageing and hence deny age as part of one’s identity (Barrett, 2022; Westwood, 2023).

STEREOTYPES, IDENTITY AND STEREOTYPE THREAT AT WORK FOR AGEING WOMEN

Stereotypes can be defined as oversimplified views concerning the nature of certain groups within society that often arise from cultural norms and allow for simplification of the cognitive mechanisms that enable people to understand their place in the world and its complexities (Hilton & von Hippel, 1996). However, stereotypes about women are often negative, including outlined representations of ageing in society that emphasise youthful attractiveness but at the same time devalue age (Ballard et al., 2009). Identity, on the other hand, is simply summarised as that which older workers psychologically internalise as their membership of a social group (e.g., “I am a woman,” “I am an older woman,” “I am an older woman manager,” “I am an older woman lower paid worker”) through social identity theory (Turner et al., 1979) and self-categorization theory (Hogg & Turner, 1987). Further to this, identity complexity reflects the amount of overlap that is perceived to exist between different group identities. Where there is a lack of overlap between categories (e.g. older woman, woman in a lower paid role) and categories are misaligned, this is associated with increasing levels of stress. Therefore, it is important to explore self-perceptions of identity in older women because stress impacts negatively on the health and well-being of older women (Roccas & Brewer, 2002).

Stereotype threat can be defined as the belief or assumption that an individual could receive demeaning stereotypes and the psychological pressure that comes with that may impact the performance of a particular task, e.g. job performance (Roberson & Kulik, 2007; Steele & Aronson, 1995; von Hippel et al., 2011). Importantly, a study by Manzi et al. (2021) examining stereotype threat in women aged 50 and over showed that ageism and gender stereotype threat represent a double jeopardy for women in the workplace.

SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE

The current research will help fill the existing knowledge gap and calls for further research to understand the intricacies of how identities of older women in lower paid roles in the workplace are constructed and how they navigate perceived stereotypes and prejudice and how other people perceive them, as well as the impacts on older women’s workplace well-being. There is limited evidence on how older women perceive themselves and are perceived in contemporary workplaces, yet this knowledge is highly important for understanding experiences of older women and effective practice and policy decision making. Therefore, the research questions are as follows:

How do older women perceive themselves in the workplace and the stereotypes and prejudice that may exist?

How do older women socially construct their identities in the workplace?

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Semi-structured interviews were used to explore the experiences and perceptions of older women’s wellbeing in an opportunity sample (N = 19) of older women aged 60 and over with a focus on those in lower paid and part time roles.

PROCEDURE

This study used an opportunity sample, recruiting from the university and other organisations (in Greater Manchester) locally where older women in lower paid part time roles may be found e.g. in the ‘5 Cs’: catering, cleaning, caring, clerical and cashiering. As illustrated in Table 1, the majority of the participants were in customer service, secretarial, and receptionist roles (38%), along with caring roles in the social care and health care sectors (21%). The interviews yielded more than 900 minutes of data at approximately 45-60 minutes per interview. The reason women over 60 years old were chosen is because this age group will be approaching/have reached or exceeded statutory pension age.

Table 1

Participant characteristics: job role

The interview questions explored older women’s current workplace and role, perceptions of being a woman and an older woman in the workplace and experiences of stereotypes and stigma, e.g.: Can you tell me about your current role? Can you tell me about your current workplace? What are your perceptions and experiences of being a woman in your current workplace? What are your perceptions and experiences of being a woman over 60 in your current workplace? What are your experiences of any stereotypes that may exist regarding women over 60 in the workplace? The dataset was part of a larger dataset also exploring well-being which will be analysed in parallel to this dataset using a different analytical lens.

DATA ANALYSIS

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with any identifiable information relating to the participant being removed. Braun and Clarke’s (2006, 2022) reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyse the data in relation to the research questions exploring self-perceptions and stereotypes. The researcher began by familiarising themselves with the data by listening to each recording, making notes, and reading each anonymised transcript, developing initial data driven codes as well as using inductive and deductive coding. A sample of the coded transcripts was checked by the supporting researcher, Giulia Bacci. Conceptual links between codes were explored and then themes were searched for, and sub-themes and conceptual links were diagrammed. An audit trail of the process was kept for purposes of confirmability. The researchers reflected on the initial thematic framework based on the full list of codes and collapsed several sub-themes into combined themes and then finally described the story behind each theme and reshaped it where required during the data process. The theoretical lens which best suited the analysis was the constructionist paradigm and the focus on experience in the data lent itself to this form of analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022). Therefore, the analysis looked specifically at how each participant experienced gender-based norms, stereotypes and workplace identities. The primary researcher (Clare Edge) reflected on her position as a younger woman and through the process kept the focus of the interview to more neutral phrases such as women over 60 rather than older woman.

ETHICS

Confidentiality, anonymity, and access to participants were considered through an ethical approval process. The recruitment of participants was carried out using a poster advertising the study that was placed in local workplaces (there was a financial incentive of £20 for taking part) such as large supermarket and store notice boards, community centres, around the university and on social media via the researcher’s work-based profiles. Ethical approval was gained from the University of Salford on 23 February, 2023 (Ethics ID: 10388).

RESULTS

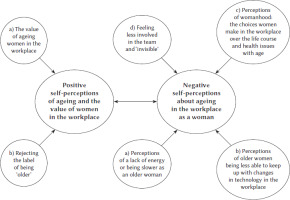

The two key themes identified in relation to the research question encompass a range of views seen across the data set in women aged 60 and over in the workplace and reflected a range of self-perceptions of being an ageing woman, which were informed by the perceived social norms and stereotypes relating to ageing as a woman in the workplace. The first theme (see Figure 1) centred on the negative self-perceptions about ageing in the workplace as a woman and had a number of sub-themes in relation to the overarching theme as follows: a) perceptions of a lack of energy or being slower as an older woman; b) a perception of older women being less able to keep up with changes in technology in the workplace; c) perceptions of womanhood: the choices women make in the workplace over the life course and health issues with age; and d) feeling less involved in the team and ‘invisible’. In contrast, many participants also reflected on the more positive perceptions of being a woman in work over 60 and were encapsulated in the theme describing the various positive self-perception of ageing (e.g. not feeling ‘older’) and the value of women in the workplace (e.g. associated with a perception of women promoting more equality and empathy).

Figure 1

Thematic map to show themes: negative self-perceptions about ageing in the workplace as a woman and positive self-perceptions of ageing and the value of women in the workplace

THEME 1: NEGATIVE SELF-PERCEPTIONS ABOUT AGEING IN THE WORKPLACE AS A WOMAN

All women described the various types of negative thoughts and feelings they had concerning their identity in relation to ageing in the workplace as a woman and deteriorations that were perceived to occur with age. These include a) having less energy, being seen as slower or less productive and b) being less able to compete with the younger generation in relation to changes and advances in technology, and c) promotions, having a life course of choices informed by caring responsibilities, meaning that career progression may have been stunted, and a feeling that older women were less included and invisible in comparison with younger women.

a) Perceptions of a lack of energy or being slower as an older woman

A range of participants in lower paid roles and senior manager roles reflected on their identity as an older worker. This was socially constructed through an internalised and externalised perception of having reduced energy levels compared to younger colleagues, which could be due to the physical nature of the role (e.g. participant 9 who was in a social care role). However, this ran in parallel to positive perceptions for many women such as participants 14 and 9, who later navigated both positive and negative perceptions of themselves including their value in their discussions. For instance, participant 8 worked as a senior manager in a large public sector organisation and reflected on feeling less energetic than she used to feel and comparing herself in her constructions of herself as tired compared to her ‘younger’ self and therefore this identity was internalised in this female worker’s sense of self:

“I think, also, sometimes you tend to think, well, I was like that 30 years ago. You know when you see new lots of energy and lots of ambition and think, yes, I remember when I used to have the energy to do that! That can be a bit frustrating at times” (participant 8, 61 years old, senior manager role, large public sector organisation).

“You are you visualized a slower, both physically and mentally” (participant 14, 68 years old, public sector manager role, large public sector organisation).

“Just not being able to properly cope, that they’re [older women] a bit past it, not as speedy as the youngsters. You have to be able to keep up, and think quickly, and if you’re a little bit more like, ‘Oh, do you want a cup of tea, love? Sit down.’… To be honest, I’ve found myself sometimes – deliberately avoiding that, because I have been irritated with some older women myself in the workplace looking to almost play into that stereotype as an avoidance tactic… I do think there’s a huge amount of subtle discrimination that goes on in that sort of way about they’re past it, they can’t keep up, and all that kind of thing, especially when you’re doing something like this, which is quite stressful” (participant 9, 64 years old, social care role, large public sector organisation).

b) Perceptions of older women being less able to keep up with changes in technology in the workplace

A range of women reflected on the role of technology and the limitations this placed on their self-image of being productive from a personal point of view in relation to internalised worries or about how others within the workplace environment view them. There was a common perception and often much discursive work around the idea that those younger counterparts who have been brought up with technology find the transition to more modern technology much less challenging than older generations and this was perceived to be a barrier to well-being in many cases. However, women felt ‘patronised’ by the younger ‘tech-savvy’ generation, describing themselves as being seen as ‘daft’, ‘stupid’, ‘dizzy’ and ‘old fashioned’ whilst also acknowledging that it was hard sometimes to keep up with technology. This represented a contradiction in women’s discussions often across the dataset and shows the discursive work they were taking on in navigating this contradiction and constructing their identities as older women and competent workers. “You’ve got to move with the times. It’s like the dinosaurs, isn’t it? You’ve got to move on or you’re extinct” (participant 5, 64 years old, customer service role, large private sector retail organisation).

“I think there’s been so many big changes in the last five years that it is quite difficult for people of my age… I’ve found it more difficult working with a group over Zoom. I like to be interacting with them, and that’s a lot easier if you’ve got them all in the same room. My workplace from that point of view, I find, is more difficult” (participant 13, 74 years old, community freelance artist and writer).

“I wasn’t brought up with phones… I wasn’t brought up with computers. We were pens and pencils, you know?… I’ll get a 26-year-old saying to me you you’re alright with these computers, aren’t you? You you’re not doing bad, and I think that’s quite patronizing sometimes” (participant 15, 64 years old, customer service role, private sector organisation).

“That would happen occasionally that somebody would be talking about a new method of writing a program to do something or whatever, and they would like sometimes to stop and explain it a little bit slower... I’ve started defining myself as old and that makes me paranoid” (participant 14, 68 years old, public sector manager role, large public sector organisation).

c) Perceptions of womanhood: the choices women make in the workplace over the life course and health issues with age

The perceptions of the choices that women make were also echoed by several women in relation to career choice, and the impact of being a woman on their self-beliefs and the roles they tend to adopt (e.g. caring roles) on the promotions opportunities they may be discouraged from going for compared to men. This self-doubt along with the physiological and psychological realities of being a woman including impacts on mental ill health, the menopause and the impacts on energy levels, the taboo, and the fear of being seen as a complaining woman, was seen as a double negative in relation to the limitations on the choices women can make. “Now, I still think if you read the business pages, you don’t see many women at that level. Certainly, if you get over 50, 60, there’s not many of us around. If I look for role models, I struggle… Above a certain level tend to be men. There are lots of women entrepreneurs who run local shops and nurseries, and that sort of thing, but when you get into the business world… there’s not a lot of them around” (participant 13, 74 years old, community artist and writer, self-employed).

“I think that constant self-doubting over time, I think it erodes you a little bit. That, along with the physiology side of things, the mental health side of things, makes it that you’re worn out!” (participant 8, 61 years old, senior manager role, large public sector organisation).

“Oh, they’ve always got… What’s it called? Menopause coming. They’ve always got that. Oh, they’re always moaning, they’re old fashioned. That’s the kind of thing you get sometimes from the younger ones. They don’t really know… ‘Silly old woman’, whereas you might have had these experiences, and when you get talking to them sometimes, they will start to listen to you. They probably think you’re a bit dim and you’ve never got anywhere. They’re a high flying whatever... and that’s from the women” (participant 6, 65 years old, medical secretary, large public sector organisation).

“I’ve had a colleague who was – she was dead sarcastic about older women. Just little snidey things. I went in one day and I’d been to the gynaecologist… She went, ‘Is that all I’ve got to look forward to?’!” (participant 2, 65 years old, customer service role, large public sector organisation).

d) Feeling less involved in the team and ‘invisible’

There was an overwhelming feeling of being undervalued compared to younger people, who were sometimes seen as waiting for older women to retire and not seeing the years of service older women have as a competitive advantage to the workplace. Women who reflected this were seen in both lower paid and part time roles as well as higher status roles. Participants also relayed the feeling of managers pushing older women out and anticipating their retirement.

“What I feel is that you feel a little bit invisible really. The younger people who start, they really don’t value you and they almost are waiting for you to retire and leave. They don’t value your work experience… Even my manager, I think he was hoping that I was going to ask to retire at 60. I think he had ideas about how he was going to rejig the department, although he’s 67 and he doesn’t have the same attitudes towards me” (participant 12, health care role, 64 years old, large public sector organisation).

“She’ll start factoring me out, somehow, because I’m on my way out. I’m sure she’d be pleased to see the back of me, actually!” (participant 9, 64 years old, social care role, large public sector organisation).

THEME 2: POSITIVE SELF-PERCEPTIONS OF AGEING (NOT FEELING ‘OLDER’) AND THE VALUE OF WOMEN IN THE WORKPLACE

In contrast to the negative viewpoints, there were a range of positive viewpoints echoed by older women about themselves in the workplace, and the sub-themes identified were as follows: a) the value of ageing women in the workplace; b) rejecting the label of being ‘older’; and c) the value of work to health and well-being.

a) The value of ageing women in the workplace

In relation to the value of ageing women, the experience and ‘kudos’ they bring to the workplace was reflected by many participants including lower paid workers and senior managers.

“I was an HR manager in my 30s, I made some horrendous decisions because I didn’t see the family behind an individual. I saw them as somebody who came into work to do the job… as you get a bit older, you think… when they went back home, they had a husband, children, this, that and the other. A more rounded individual where you can see them more holistically as you get older. I definitely think that comes with age” (participant 8, 61 years old, senior manager role, large public sector organisation).

“I think when women are directors, they’re less, ‘I’m a director’ sort of thing, from my experience in my workplace at the moment. I would say it’s equal, the level of jobs” (participant 4, 60 years old, public health role for large public sector organisation).

“…there have been other occasions where I feel that being the older person has given me more kudos...” (participant 14, 68 years old, public sector manager role, large public sector organisation).

“I think a lot of people come and ask you questions because you’re older and they think you know where everything is. I think some people might be embarrassed about asking questions to a younger person” (participant 5, 64 years old, customer service role, large private sector retail organisation).

b) Rejecting the label of being ‘older’

Several participants, including those in lower paid roles, talked about their perception of themselves in work and the value of being part of the team in connection to rejecting the notion of being old or any associated negative stereotypes rather than the value of age per se.

“Funnily enough, the management there, they love me… they don’t want me to leave, even though I’m 80, they don’t want me to leave. They want me to stay… nobody ever believes I am the age I am; you see. So, they just treat me like they would anybody” (participant 7, 80 years old, customer service role, private sector retail organisation).

“For me, personally, I don’t want to be seen as somebody who’s passed the sell-by date in the workplace” (participant 9, 64 years old, social care role, large public sector organisation).

DISCUSSION

The current research illuminated the self-perceptions and experiences of women in work aged 60 years old and over, with a focus on lower paid roles, in the workplace as well as the stigma and prejudice perceived to be associated with being an ageing woman. The study identified several key drivers to negative and positive self-perceptions in the workplace surrounding perceptions of older women. These included them being perceived as slower and less productive compared to younger workers, as well as less able to cope with changes in technology, the limitations on women in relation to choices they make in their career, the need for flexibility, and a sense of being seen as different to men. The needs of women across the life course were not always seen as an advantage or viewed favourably by colleagues. The health challenges issues women face with age were often seen as detrimental by women themselves and colleagues although the value of women’s experiences was often articulated in the discourses of women in tandem to perceptions of any limiting factors. Compellingly, there was an overwhelming feeling amongst women in lower paid roles of being less involved and being seen as invisible compared to younger workers and a perceived sense of discrimination. This highlights the need for intergenerational work and for more emphasis on the value of older women in work to address the root causes of gendered ageism including masculine and young ideal worker norms (see, for example, North & Fiske, 2015; Reid, 2015). A key worker identity perception was reflected by women in lower paid roles as well as those in senior roles of the value of older women in the workplace and a feeling that women have experience to impart and ‘kudos’.

The current findings mirror previous research showing the negative impacts of the intersection of age and gender on women; specifically, that a stereotype threat exists around being an ageing woman and older women having a sense of invisibility in the workplace in relation to their sense of selves as older women workers, which was reflected by women in both lower paid and senior roles (Bowman et al., 2017; Manzi et al., 2021; Sabik, 2015; Westwood, 2023). Conversely, a contradiction was highlighted whereby women found themselves perceiving themselves as having value despite the limitations that come sometimes with age, e.g. cognitive and memory decline, that made learning new technology systems sometimes challenging. Despite these challenges, they expressed the desire to be independent in relation to their occupational identity versus their identity as an ‘older female worker’ compared to a ‘tech savvy’ younger generation. This highlights the importance of exploring identity complexity across the intersections of occupational, status, gender and age identity (Roccas & Brewer, 2002). In addition, it is important to understand the negative impacts of stereotype threat on productivity, specifically as regards technology-based productivity, as well as the potential links to stress. This includes the need to reduce stress accumulation in women across the life course identified in the UK (Miller et al., 2022).

The current study also highlighted more positive accounts of ageing identity as a woman over 60 in the workplace whereby their value was echoed by a range of women and some perceived managers to be supportive of them and their added value. It was reflected in promoting the value of ageing women in work and rejecting the label of being ‘older’ as a mechanism by which older women could perceive themselves more positively in the workplace. This runs in parallel to the notion of ageing as a performance whereby rejecting the notion of being ‘old’ is seen as performing well at ageing and overlaps with ageing as identity, whereby ageing is seen as incompatible with a positive sense of self and for women particularly whereby lookism (gender identity) is combined with ageism (ageing identity) (Barrett, 2022). This notion of rejecting the label of being older relates to the concept of stereotype threat (Manzi et al., 2021), which highlights the need for workplaces to harness the competitive advantage of women and their life experience to reduce perceptions of stereotypes in work.

This could be harnessed in the workplace as women are shown to be more likely to work for longer than men in the United Kingdom (Finch, 2014), for example, by enabling women to feel positive in the workplace by reducing negative self-perceptions, e.g. by intergenerational work. The current findings are transferable to workplaces with lower paid older women in the workforce as well as workplaces with representation of women in the ‘5 Cs’ (catering, cleaning, caring, clerical and cashiering).

The current study has some limitations. Firstly, the findings may not be transferable to some workplace settings, e.g. highly skilled settings. Secondly, the study is limited to the Northwest of England, because this was the geographic location of the study and because of the characteristics of the region. Specifically, a prominent ‘North-South divide’ can be seen, with those in the South expected to live longer and remain healthier on average than those in the North of England. Variations also occur according to ethnicity, cultural background and country because of factors such as differing social norms around gender roles, pension and gender equity policies and levels of gender care and gender health gaps.

Future studies should focus on recruiting older women with a broad age range and from a diverse background to incorporate self-perceptions of being in work through the menopause, perimenopause and other life stages. Cross-cultural comparisons should also illuminate the complexities of women’s experiences across the life course and highlight the importance of context to women’s experiences.

The current study highlights the need to explore further the self-perceptions of women, stereotype threat and identity complexity as well as the drivers of stereotypes and prejudice in relation to implied norms and assumptions of women as they age. Future research should respond to this need by amplifying the voices of older women in lower paid and part time roles in response to the overwhelming feeling seen across the dataset that with age as a woman comes ‘invisibility’.