BACKGROUND

Nowadays, students experience an excessive burden, as a result of which they are unable to function effectively in school and they can hardly tolerate all kinds of school failures (Rosales-Ricardo et al., 2021). Exhausted students often use maladaptive coping strategies that may entail a child becoming addicted to the Internet (Özdemir & Arlsan, 2018). Academic research on addictive Internet use, as a serious psychological disorder, began in the mid-1990s (Heo et al., 2014). The terminology often used to describe this addictive behavior includes: “problematic Internet use”, “excessive Internet use”, “Internet addiction”, “Internet overuse”, “compulsive Internet use” and “pathological Internet use” (Tong et al., 2019; Restrepo et al., 2020; Toth et al., 2021). It is worth adding that the term “problematic Internet use” or “problematic use of the Internet” (PUI) is recommended as a neutral alternative because it does not imply the presence of psychopathology (Restrepo et al., 2020). The term PUI indicates the inability to control an online behavior (compulsivity), social withdrawal from real life and bonds as well as the increase tolerance of Internet use (Hsieh et al., 2021). School burnout also had a short history of coverage in scientific studies (research began in the late 1970s in the occupational context, and then was extended into the school context at the beginning of the 21st century) (Aypay & Sever, 2015). Despite its short history, both these problems emerged in parallel with a dramatic increase, and became prevalent especially among adolescents (Restrepo et al., 2020; Rosales-Ricardo et al., 2021). Moreover, previous studies confirmed the strong link between these variables and psychological well-being and depression. In particular, past studies have suggested that in male groups depression leads to problematic Internet use (mood enhancement roots of problems), and in female groups problematic Internet use leads to depression (social displacement roots of problems) (Liang et al., 2016). Additionally, numerous studies have confirmed the strong predictive power of school burnout for the risk of depression symptoms (Elkins et al., 2017; Fiorilli et al., 2017). This study provides information that allows for a better understanding of problematic Internet use and student school burnout in the youth group.

COPING STRATEGIES AND PROBLEMATIC INTERNET USE

Dealing with stress according to Heszen (2008) can be considered in two ways. First of all, it is an individual’s activity focused on positive change or improvement of the health condition of a person. Counteracting stressful situations is effective when a person is able to self-evaluate their own mental health and recognize and understand their ability to cope with difficult situations, which requires them to have a basic knowledge about stress and different strategies and ways of coping with it. Research conducted by Oláh (1995) showed that adolescents used constructive and assimilative coping strategies at low and medium levels of anxiety, while they used avoidance behaviors at high levels of anxiety. Previous studies have confirmed that people with difficulties in coping with real-life problems and situations are more prone to develop problematic Internet use (Chou et al., 2015). Tonioni et al. (2014) believe that people addicted to the Internet most often use impulsive coping strategies. McNicol and Thorsteinsson (2017) in their research found that there is a relationship in adolescents presenting avoidance strategies and mental suffering and problematic Internet use. Kardefelt-Winther (2014) believes that people addicted to Internet activity treat it as a kind of way of dealing with everyday problems.

Research conducted by Tomaszek and Muchacka-Cymerman (2020a) aimed to determine the predictors of students’ school burnout, related to the way of reacting to stressful situations, i.e. presenting strongly competitive behaviors and different ways of coping. The only factor protecting children and adolescents from experiencing exhaustion turned out to be the disposition of an active style of coping with stress.

SCHOOL BURNOUT AND PROBLEMATIC INTERNET USE

The literature review shows that to date many of the studies have described occupational burnout, with the tests consisting of attempts of adults representing various professional environments (Özdemir & Arlsan, 2018). There are far fewer studies devoted to pupils’ school burnout. However, this phenomenon is common among young people (Rosales-Ricardo et al., 2021). For school burnout, the subjective negative assessment of fulfilling the role of the student, i.e. acknowledging oneself as a weak student, is crucial (Tomaszek & Muchacka-Cymerman, 2020b). When the student acknowledges himself/herself as weaker than others, then hostility, a low level of disposition for active coping with stress and exhaustion of the subject appear. Research conducted by Schulte-Markwort (2015) shows that the problem of school burnout is affecting a growing group of young people. Among the many reasons, the main predictor is constant stress.

What is more, pupils experiencing school burnout more often present univocal behavior focused on isolation from the group, aggressive behavior and have inappropriate relationships (in the school and family environment) (Figueroa et al., 2019; Tomaszek, 2020). Some teenagers’ behavior results in a lack of self-efficacy, and poor or no resistance to stress, which leads to a weakening of motivation. These factors largely cause the emergence of various forms of activity, one of the most severe being addiction to the Internet. The results from research carried out by Kalpidou et al. (2011) show that spending a lot of time on Facebook is associated with low student self-esteem. Moreover, addiction to the Internet has a negative impact on the sense of mental well-being (Cardak, 2013). Using the Internet to reduce stress contributes to the addiction of the individual (Tang et al., 2014). To date, only a few studies have explored the link between problematic Internet use and school burnout. However, all have indicated a significant positive connection between these variables (Salmela-Aro et al., 2017; Imani et al., 2018; Peterka-Bonnetta et al., 2018). Additionally, in the study conducted by Salmela-Aro et al. (2017), adolescents with school burnout were at higher risk of becoming later Internet addicts and vice versa. Furthermore, male adolescents suffered from excessive Internet use, which later spilled over into depressive symptoms.

THE INTERACTION BETWEEN COPING STRATEGIES, BURNOUT SYNDROME AND ADDICTIVE BEHAVIORS – THEORETICAL BACKGROUND FOR STUDY HYPOTHESIS

Stress and burnout are inherently related to each other as burnout is a consequence of stress that a student cannot deal with because of using maladaptive coping strategies (Bakker & de Vries, 2021). According to general strain theory the experience of strain or stress activates negative emotions and in turn generates pressure for corrective action; however, usually it is ineffective because of using maladaptive coping behaviors, to escape from the source of the adversity (Agnew, 2001). Moreover, in the BAT model burnout symptoms are maintained because of impairment of emotional and cognitive self-regulation processes, and this is the core reason for individuals to develop mental and behavioral problems, e.g. depression or addictive behaviors (Schaufeli et al., 2020). According to Bakker and de Vries (2021) the deficits in flexibility of the coping mechanism results in the inability to select the correct coping strategy and adaptive behavior. Therefore, the level of psychological distress and the severity of mental problems gradually increase. In accordance, the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model by Brand and colleagues (2019) suggests the existence of an inner circle that explains the development of a problematic and addictive behavior. Particularly, the person’s core characteristics (general predispositions, e.g. dysfunctional coping styles, and behavior-specific predispositions, e.g. specific motives, values and needs) determine the perception of external (e.g., confrontation with behavior-related stimuli) or internal triggers (e.g., negative or very positive moods) of the situation, and this may result in affective and cognitive responses which specify a further response to a problem (e.g. the decision to behave in a specific way – to increase personal engagement in the Internet). According to the I-PACE model the relationships between all abovementioned elements are moderated by the level of general inhibitory control and self-regulation/self-directedness. Interestingly, in burnout because of the exhaustion and lack of energy to effectively regulate one’s emotional and cognitive processes the functional capacity is also impaired (Schaufeli et al., 2020). Brand et al. (2019) explained this dysfunctionality of addicted people by pointing out the link between addictive behavior and the feelings of gratification or relief from negative moods (a form of compensation). Similarly, in the JD-R model of burnout individuals engage themselves in maladaptive behaviors (confusion, stress, problems, conflicts) that increase obstacles because of high demands and strain as well as lack of self-control (self-undermining process) (Bakker & Demerouti, 2018; Bakker & de Vries, 2021). It is also worth noting that burned out people often suffer from depressed mood and use mental distancing as a self-protection reaction. The I-PACE model suggests that the reason for the persistence of imbalances between key regulatory processes are positive experiences that modify the subjective reward expectancies and the individual coping style (e.g. although the coping strategy is ineffective and escalates the problems the student continues to use it). Over time, these relations became more rigid and severe and contribute to the development of habitual problematic behaviors. In later stages positive subjective expectancies about addictive behavior may evolve into affective and cognitive biases (e.g. biased or seemingly automatic concentration on the specific behavior-related stimuli and triggers) (Brand et al., 2019).

RESEARCH MODEL

Respectively to the theoretical framework described above in this study, we examined the association between coping strategies, student school burnout and problematic Internet use. The first goal of the study was to investigate the mediation effect of school burnout on the association between coping strategies and problematic Internet use. It was hypothesized that school burnout mediates the relationship between less adaptive (avoidance and emotional – focused) coping and problematic Internet use, but not the association between problem-focused coping strategies and problematic Internet use. According to Cheng et al. (2014), avoidance and emotion focused coping are adaptive in the short term (because they create opportunities for recovery), and maladaptive in the long term (because the stressor is not controlled). We believe that because of impairment in the emotional and cognitive self-regulation process typical for burnout and addictive behaviors, these coping strategies are used in a rigid way and will be related to problematic Internet use via burnout symptoms. This effect will not be seem in problem-focused coping because it relates to the individual’s efforts to solve the problem and to control the stressor. However, burned out students are too overwhelmed and have problems to effectively analyze the situation and addictive people tend to make affective and cognitive biases when analyzing strategies.

The second goal was to extend previous research on coping, school burnout and problematic Internet use by exploring the role of gender. Past studies have confirmed the significant gender differences in the levels of student burnout (girls are more prone to develop symptoms of this syndrome) (Backović et al., 2012), problematic Internet use (boys more often present addictive behaviors related to the Internet) (Rigelský et al., 2021), and coping strategies; according to Eschenbeck et al. (2007), girls scored higher in seeking social support and problem solving, whereas boys scored higher in avoidant coping, although a recent study conducted by Alkaid Albqoor et al. (2021) on a group of adolescents revealed that girls used avoidance and approach coping strategies at higher levels than boys. Some past studies have revealed a complex relationship between the escape-avoidance coping style and addictive Internet use that differ between genders (Poprawa et al., 2019). In addition, some researchers suggest that the link between burnout and excessive Internet use is moderated by gender (Tomaszek & Muchacka-Cymerman, 2020a). Therefore, we hypothesized that gender will be a significant predictor of problematic Internet use and will have a moderating effect on the association between coping and problematic Internet use as well as between student burnout and problematic Internet use.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study included 230 students aged 17 to 20 years. The average age of the subjects was M = 18.25 years, SD = 0.45, while 26% were male. The subjects were randomly selected on the basis of one type of secondary school in Poland: high school, from different regions in Poland (Gdańsk, Warsaw, Cracow). The subjects volunteered for the survey.

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted in classes. The participants were asked to complete each test in the study and were informed about the method and about the anonymity and purpose of the study. The students did not receive any payment for participation in the research. The parents of the students under the age of 18 consented to the study. The school heads agreed in exchange for general feedback on the topic raised in the study and for a description of the problems raised in the studies on the pedagogical council. The study was approved by the Pedagogical University Ethics Committee (WP.113-6/2019).

MEASURES

Mini-COPE scale – originally created by Carver et al. (1989); in the Polish adaptation of Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik (2009). The instrument has 28 items describing different patterns of reacting to a stressful situation, with a response format on a Likert-type frequency scale with 0 – I haven’t been doing this at all to 3 – I have been doing this a lot. The scale includes 14 coping reactions. In the Polish version these reactions are matched to 7 factors. Two of them are more effective and related to problem-focused coping – active coping and acceptance; the other five are less effective – avoidance behaviors, helplessness, sense of humor, turning to religion, searching for support. Avoidance behaviors and helplessness are treated as poor coping strategies (Juczyński & Ogińska-Bulik, 2009). In this study McDonald’s ɷ ranged from .40 (sense of humor) to .83 (searching for support), and Cronbach’s α from .39 (sense of humor) to .83 (searching for support).

Secondary School Burnout Scale (SSBS; Aypay, 2012) consists of 34 items with seven sub-scales, i.e.: LIS – loss of interest in school; BDS – burnout due to studying; BDF – burnout due to parents; BDH – burnout due to doing homework; BTT – being bored and tired of teacher attitudes; NRF – need to rest and have fun; ISS – incompetence in school; SSB – student school burnout. All questions have been evaluated on the Likert scale from 1 (I totally disagree) to 4 (I totally agree). When the participants assessed how strongly they identify with the question, their answer was X in the appropriate space under the scale. The lower the SSBS score, the higher was the burnout result for that student. For the SSBS total score reliability in this study was indicated by McDonald’s ɷ = .89 and Cronbach’s α =. 87.

Problematic Internet use test (PUI) based on the Internet Addiction Diagnostic Questionnaire (IADQ; Young, 1998). The Polish version of the scale was developed by Poprawa (2011) and named Problematic Use of the Internet (PUI). PUI consists of 22 questions to which the examined person applies the 6-point Likert scale. In this study both McDonald’s ɷ and Cronbach’s α were equal to .90.

DATA ANALYSIS

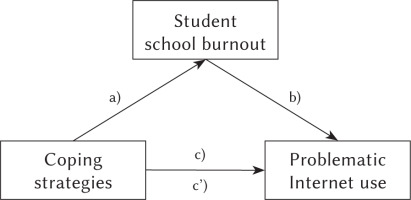

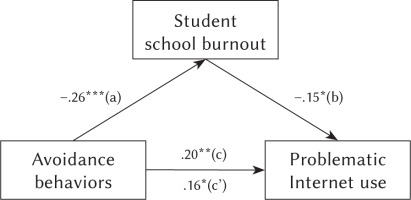

The current study’s main purpose was to investigate the indirect effect of coping strategies on problematic Internet use via student school burnout (i.e. mediation effect). In order to examine this mediation role of student burnout, several multiple regression models were built. Specifically, seven coping strategies (active coping, helplessness, avoidance behaviors, sense of humor, turning towards religion, search for support, acceptance) were separately tested for their direct and indirect effects on problematic Internet use level (see Figure 1).

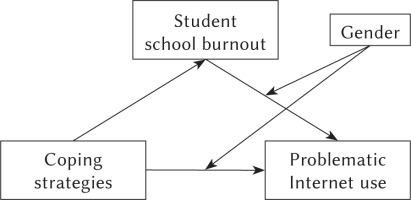

To test the indirect effect of the independent variable (coping strategies) on problematic Internet use via student school burnout (named C’ relation) the percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 re-samples (Model 4), implemented with the PROCESS macro version 3, was conducted (Hayes, 2013). In addition, we examined the moderation mediation models (model 15 by Hayes) to examine the role of gender in the associations between tested variables (see Figures 1 and 2). All statistical analyses were tested with SPSS version 22.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Higher student school burnout correlated with higher problematic Internet use (Pearson’s r = –.19, p = .004). Additionally, both were associated with poor coping, e.g. avoidance behaviors and helplessness. Lower student burnout was associated with higher active coping as well as turning to religion and searching for support (Pearson’s r ranged from .14, p = .031 to .21, p = .002). Higher problematic Internet use correlated negatively with more effective coping strategies, e.g. active coping and acceptance (Pearson’s r ranged from –.20, p = .003 to –.22, p = .001). The Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to compare the level of tested variables in boys and girls. The results revealed only two significant gender differences, i.e. higher level of burnout (z = –4.18, p < .001) and more frequent use of avoidance coping in the girl group (z = –2.32, p = .020).

THE MEDIATION EFFECT OF SSBS ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COPE AND PUI

According to regression analyses, four coping strategies significantly predicted the problematic Internet use level: active coping, helplessness, avoidance behaviors and acceptance. Others, such as searching for support, sense of humor and turning towards religion, did not have significant associations with the problematic Internet use level. Also, one coping strategy – acceptance – although significantly predicting problematic Internet use (F = 10.98, ∆R2 = .04, p = .001; β = –.22, p = .001), did not predict student school burnout (F = 1.07, ∆R2 = .01, p = .303; β = .07, p = .303). Taking this into account, three mediation analyses were conducted. The results for indirect effects are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

The role of gender in the relationship between SSBS, COPE and PUI

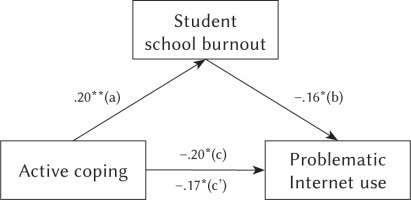

The direct effects of the active coping strategies on student school burnout and problematic Internet use were significant, with F = 9.97, ∆R2 = .04, p = .002, and F = 9.20, ∆R2 = .04, p = .003, respectively. Specifically, active coping strategies significantly predicted the student school burnout with a standardized coefficient = .20, p = .002, and problematic Internet use with a standardized coefficient = –.20, p = .003. The mediating effect of student school burnout was observed as the impact of the independent variable on problematic Internet use total score decreased. These results were also confirmed by the bootstrap method (β = –.03, SE = .02, 95% CI [–.08, –.002]) (see Table 1, Figure 3).

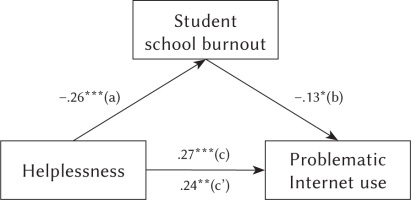

The next analysis examined the relationship between helplessness, student school burnout and problematic Internet use. Helplessness was significantly associated with student school burnout (F = 18.22, ∆R2 = .07, p < .001; β = –.27, p < .001) and problematic Internet use (F = 17.75, ∆R2 = .07, p < .001; β = .27, p < .001). In the regression model conducted to evaluate the association between the combination of helplessness and student school burnout, the statistics for the model were significant F = 10.87, ∆R2 = .08, p = .001; but only helplessness yielded a significant result with problematic Internet use; β = .24, p < .001; unexpectedly, the student school burnout standardized coefficient was lower and borderline significant (β = –.13, p = .053). A mediation effect was also noted as the relationship between helplessness and problematic Internet use was weaker after entering student school burnout into the regression model. The indirect effect was confirmed by the bootstrap method (β = .03, SE = .02, 95% CI [.002, .08]) (see Table 1, Figure 4).

In the next regression analysis we tested the mediating effect of student school burnout on the relationship between avoidance behaviors and problematic Internet use. All the direct effects were significant, specifically the effect of avoidance behaviors on problematic Internet use (F = 9.45, ∆R2 = .04, p = .002; β = .20, p = .002) and on student school burnout (F = 17.12, ∆R2 = .07, p < .001; β = –.26, p < .001). The regression model testing the indirect effect confirmed the mediating role of student school burnout (F = 7.26, ∆R2 = .05, p = .001). The standardized β = .16, p = .017 for avoidance behaviors was significant, but lower after entering the mediator. The results of the bootstrap method indicated a significant indirect effect (β = .04, SE = .02, 95% CI [.01, .09]) (see Table 1, Figure 5).

Several regression analyses were conducted to examine the mediation role of student school burnout after controlling for the effects of gender. Firstly, we conducted simple regression analysis for problematic Internet use. In the regression model we included gender, coping strategies and school burnout as the explanatory variables. The results showed that gender, student school burnout and one coping strategy – acceptance – were significantly associated with problematic Internet use. Parameters of the regression model: ∆R2 = .15, F = 5.45, p < .001 (see Table 2).

Table 2

Multiple linear regression model of problematic Internet use

The moderated mediation models (model 15 by Hayes) were conducted to examine the interaction effects of (1) gender with all seven coping strategies and (2) gender with student school burnout. All interaction effects for gender and coping strategies were insignificant. In all seven tested models the interaction effects between gender and student burnout were significant (B ranged from –.47, p < .001 to –.60, p < .001, 95% CI did not include zero, indicating significance of all tested effects). These effects indicated that boys experience a faster increase in student burnout and that this is related to much faster increase in problematic Internet use than in girls.

The results above suggested that gender may play a significant role in the relationship between tested variables. This justified the last part of the analysis, which involved testing the mediation effects of student school burnout on the association between coping strategies and problematic Internet use separately for females and males. Surprisingly, in the female group student school burnout did not significantly predict problematic Internet use (F = 1.18, ∆R2 = .00, p = .279; β = –.08, p = .279). In the group of male students, searching for support (F = 0.20, ∆R2 = –.01; β = –.06, p = .657), acceptance (F = 3.16, ∆R2 = .03; β = –.23, p = .081), sense of humor (F = 0.34, ∆R2 = –.01; β = .08, p = .564), and turning to religion (F = 1.50, ∆R2 = .01; β = .16, p = .226) were not significantly associated with problematic Internet use. Moreover, active coping, and searching for support did not significantly predict student school burnout (F = 3.82, ∆R2 = .05; β = .25, p = .056; F = 3.55, ∆R2 = .04; β = .24, p = .065, respectively).

For the above reasons, only two mediation effects were observed. In the first two models, helplessness had a significant direct effect on problematic Internet use (F = 12.73, ∆R2 = .18, p = .001; β = .43, p = .001) and student school burnout (F = 8.51, ∆R2 = .12, p = .005; β = –.36, p = .005). The regression model testing the direct effect of student school burnout on problematic Internet use was also significant (F = 20.91, ∆R2 = .26, p < .001; β = –.52, p < .001). The indirect effect of helplessness on problematic Internet use via student school burnout was confirmed (B = .15, SE = .07, 95% CI [.03, .31]).

In the next regression analysis, the mediation effect of student school burnout on the relationship between avoidance behaviors and problematic Internet use was tested. The direct effects for both the independent variable and the mediator were significant; avoidance behaviors significantly predicted the level of problematic Internet use and student school burnout (F = 11.76, ∆R2 = .16, p = .001; β = .41, p = .001; and F = 7.80, ∆R2 = .11, p = .007; β = –.35, p = .007, respectively). The indirect effect was also confirmed by the bootstrap method (B = .15, SE = .08, 95% CI [.01, .34]) (see Table 3).

Table 3

The mediation effect of the coping strategies on Internet addiction via student school burnout (Nmale = 59)

DISCUSSION

Recent research shows an increased concern over the socio-digital participation of young people and the risk factors connected with the problematic Internet use in this group (Tong et al., 2019; Hsieh et al., 2021). This subject is so important because, according to researchers, it negatively affects both school-related problems and the mental health of young people (Buzzai et al., 2021). Our findings help to obtain a better understanding of relations between coping strategies, school burnout and problematic Internet use.

The results indicated the significant associations between poor coping strategies, low active coping, student burnout and problematic Internet use. We also confirmed that student school burnout mediates the link between coping strategies and problematic Internet use among adolescents. In addiction, our findings suggest the significant moderation effect of gender on the relationship between student school burnout and problematic Internet use. Students with a lower level of problem-focused coping strategies (active strategies, acceptance) and with a higher level of helplessness and avoidance behaviors are generally more vulnerable to addictive Internet behavior. These results are similar to the previous findings that better coping strategies are protective against the risks of problematic Internet use problems, and that ineffective and poor coping strategies are one of the risk factors of this phenomenon (Yao et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2014; Mak et al., 2018). A further examination in this study revealed that these connections are enhanced by student school burnout, but only for three coping strategies. The findings showed the significant mediation effect of school burnout on the association between problematic Internet use and one problem – focused coping strategy – active coping, and two poor coping strategies – helplessness and avoidance behaviors. This may be connected with two characteristics of Internet addicted students – poor time management problems and withdrawal (Young, 1998), along with lower stress tolerance, impulsivity and behavioral problems (Mak et al., 2018; Tang, 2018), as well as a variety of educational difficulties, such as decreased ability to concentrate during lessons or poor school productivity and lower school performance (Li et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017).

Our results demonstrate that gender, student school burnout and coping strategy – acceptance are significant predictors of problematic Internet use. In addition, gender moderated the relationship between school burnout and problematic Internet use, but did not moderate the associations between coping strategies and problematic Internet use. Thus, the second study hypothesis was only partially confirmed. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the indirect effects of coping strategies (active coping, helplessness, and avoidance behaviors) via school burnout on problematic Internet use differ according to gender. In addition, a significant mediation effect was noted in the male group, but not in the female one. However, after controlling for sex differences, only two coping strategies were indirectly associated with problematic Internet use level in the male group, i.e. helplessness and avoidance behaviors. Overall, the results suggest that a male adolescent with poor coping strategies is more prone to school burnout and, because of being burnt out, is at greater risk of becoming an Internet addict. In the female group, school burnout did not significantly predict problematic Internet use. Poprawa et al. (2019) stated that pathological Internet use is conditioned by specific psychopathological symptoms and personality susceptibility via the mediating function of escape coping strategies and the outcome expectations of Internet use. Furthermore, according to Jang and Ji (2012) males’ overuse of the Internet may be related to higher desires to escape into cyberspace as a self-soothing behavior or self-medication in reaction to internalized depressed mood. Easier immersion in the virtual world for boys may indicate inaccessibility of other strategies when experiencing a stressful situation. Subjective acceptance and easy availability of an online activity may also be a more rewarding strategy to deal with everyday problems than problem-focused coping. This tendency may also be connected to sociocultural customs that protect women from excessively using the Internet when they are stressed (Su et al., 2019). Specifically, boys often receive less support and supervision from their families, and that may increase the risk of spending too much time on the Internet (Yu & Shek, 2013).

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations of our study. With a cross-sectional study design and a relatively small number of participants (especially the male sample – 26%), this research can only make suggestions about how to handle this problem and to explore possible causal relationships between the major variables, which could not be generalized. The variables used to define the school burnout and problematic Internet use levels were based on self-reported information that may be biased. Moreover, the participants described the subjective perception of their serious problems with a technological behavioral addiction pattern, so the real level of their problems might be decreased because of recall biases and defense mechanisms, and these could also affect our findings. According to previous literature, several forms of problematic Internet use exist, so the mediation effect of school burnout on the link between coping strategies may not be generalized to all types of problematic Internet use. However, despite these limitations, our findings are consistent with previous studies and have expanded them by identifying a possible moderating effect of gender on the link between coping strategies, school burnout and problematic Internet use.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study provide empirical insights into the association between coping strategies, burnout syndrome and problematic Internet use among adolescents. In the light of our results, deficits in coping resources increase the risk of developing burnout symptoms and this may be connected with excessive Internet use that indicates health impairment. Therefore, to be able to effectively counteract stressful situations, adolescents should be able to self-assess their own mental health as well as to recognize and understand their ability to cope with difficult situations, which requires them to have a basic knowledge about stress and different strategies and ways to deal with it. As noted by Lam et al. (2009), psychologists need to be aware of the potential diseases associated with problematic Internet use, such as stress and family dissatisfaction. In addition to the factors protecting against burnout, and thus the use of appropriate, adequate coping strategies, the school could offer its pupils a very effective technique – that of supervision. Chou et al. (2015) after conducting their research drew attention to the strategies of coping with stress as an important factor to evaluate during the development of intervention programs.