BACKGROUND

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic poses a global challenge for countries and nations all over the world. Numerous studies have indicated adverse effects of this situation for various aspects of psychological functioning, related to deterioration of happiness (Espinosa et al., 2022; Greyling et al., 2020) and increased levels of emotional distress (de Quervain et al., 2020; Nowakowska, 2020). The negative consequences for well-being and mental health are observed in both people infected with COVID-19 (Zajenkowska et al., 2023) and those not infected but exposed to pandemic restrictions such as the lock-down and other constraints (Greyling et al., 2020). Taking into consideration the severity of the pandemic combined with the fact that further waves of COVID-19 are expected and the recovery process at the societal level is estimated to last for years, it seems vital to identify psychological resources that can help in coping with this challenging situation. In this article, we propose that an overall positive attitude towards other people (expressed in trust and prosocial orientation) is important for assessing emotional outcomes of the pandemic – we expect it to be linked to lower levels of stress and higher levels of happiness. At the same time, given all the negative consequences of experiencing COVID-19, we presume that the infection can alter these beneficial effects.

How is caring for others related to effective mood regulation? According to the negative state relief hypothesis (Cialdini et al., 1973), the process of helping can be perceived as a mood-enhancing reward leading people to prosocial behaviours when they feel bad. The frequency of taking up activities for the benefit of others and expressing intentions to do so is related to a higher level of happiness (Jasielska, 2020). According to Ng and Diener (2022), prosocial behaviour buffers the detrimental effects of stress on subjective well-being. The relationship between prosocial behaviour and subjective well-being has been documented by them on a global scale, on large samples in cross-cultural research, and turned out to be universal (Ng & Diener, 2022).

Recent studies conducted in the context of COVID-19 confirmed a significant role of prosocial behaviour in maintaining well-being. In a study on Colombia’s general population, engaging in supporting others enhanced life satisfaction and decreased the impact of pandemic-related negative emotions (Espinosa et al., 2022). Another study indicated that spending money on others led to higher levels of self-reported positive affect, empathy, and social connectedness (Varma et al., 2023). Given the relationship between actual prosocial behaviour and well-being, observable also in the COVID-19 context, it seems worthwhile to investigate whether a general, stable disposition towards benefitting others is also related to the emotional state during the pandemic.

Among the indicators of declared prosociality are social value orientations (SVOs). They describe what importance people ascribe to the gains to oneself and other people in situations of interdependence (Messick & McClintock, 1968). For example, will they share valuable resources with others instead of keeping them to themselves? SVOs are often measured in terms of choices made by decision makers regarding distribution of money and indicate the level of concern that one has for others’ welfare (Murphy et al., 2011). These choices vary from pro-self orientations (with people labelled as competitors who maximize the difference between their own and others’ outcomes and as individualists who maximize their own gains, irrespective of others’) to prosocial orientations (prosocials who equalize and/or maximize joint outcomes and altruists who amplify others’ outcomes). Studies have shown that SVOs are linked to prosocial behaviour in experimental and real-life situations. For example, a meta-analysis indicated that in a social dilemma situation prosocials, compared to pro-selfs, are more focused on cooperation with a partner (Pletzer et al., 2018). Prosocials also reported that they engaged in a greater number of donations, mainly supporting the poor and the ill (Van Lange et al., 2007). SVOs are also linked to a higher level of happiness, but only when combined with an elevated level of trust (Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020). This implies that having faith in good intentions of other people is a significant factor in the relationship between expressing concern for others and happiness. In a longitudinal study conducted at the beginning of the pandemic, SVO levels remained unchanged in successive measurements (Van de Groep et al., 2020), which implies that they are a good indicator of a stable disposition in the COVID-19 context.

Another dimension of a positive attitude toward others is trust, which is related to the expectation of positive rather than negative outcomes of the actions of others (Ashraf et al., 2006; Johnson & Mislin, 2011; Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994). Trust is considered as one of the strongest predictors of prosocial behaviour (Irwin, 2009). It is also linked to other socially desired qualities and behaviours, such as social solidarity, tolerance, cooperation, optimism, volunteerism and donation to charity (Ashraf et al., 2006; Rothstein & Uslaner, 2005). The links between trust and various aspects of subjective well-being are recognized at both the societal and individual level (Helliwell et al., 2021; Jasielska et al., 2021). Studies on consequences of COVID-19 have emphasized the importance of public trust in supporting successful responses to the pandemic such as following restrictions designed to stop the spread of the virus (Helliwell et al., 2021; Jasielska et al., 2023). Level of trust was also an important factor explaining the national level of happiness during COVID-19 and helping countries to provide resilience in the face of a pandemic (Helliwell et al., 2021). The ability to express trust seems to be a vital resource that can help cope with the negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

CURRENT STUDY

There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic, the biggest global health crisis in the last century, is a challenging experience for nations all over the world, due to several reasons – among others, the lock-down and isolation, limited interpersonal contacts, enforced remote work, fear of infection and finally – to many people – the burden of going through the disease. Such a situation can be linked to stress (Bodecka et al., 2021) and depression (Zajenkowska et al., 2023). Therefore, it is particularly important for psychologists to identify assets that would facilitate coping with negative emotional consequences of the pandemic.

Previous studies have indicated that a valuable source of these resources could be factors that comprehensively enhance social functioning and are linked to elevated happiness and subjective well-being, such as trust and prosocial behaviour. The latter two are related not only to higher well-being (Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020; Ng & Diener, 2022) but also to implementing more successful strategies for fighting the pandemic (Helliwell et al., 2021). In the World Happiness Report 2021, which provided extensive data on indicators of happiness during the pandemic (Helliwell et al., 2021), the measurement of institutional trust and benevolence was based on a “wallet question”. Participants were asked to assess the likelihood of their hypothetically lost wallet containing $200 being returned by a policeman, a stranger or a neighbour. As it turned out, the higher the faith was in the lost item being returned, the higher was the national well-being and the lower was the COVID-19 death rate. However, this method does not assess general trust, nor does it measure actual benevolence towards others (to what extent “I” am willing to act prosocially). Measuring general trust and social orientations seems therefore to be an important undertaking, as the trust itself relates to much more than having faith in public institutions. Similarly, ascribing good intentions to other people is not equal to personal inclinations towards caring for them. Measuring both trust and SVO can show to what extent an overall attitude towards other people (expecting positive outcomes from social interactions combined with the willingness to benefit others) is linked to coping with the pandemic. A number of studies (for example Dębowska et al., 2022; de Quervain et al., 2020) have focused mainly on experiencing negative emotions in the face of the pandemic. In our study we assessed both negative (COVID-19 distress) and positive states (subjective happiness). This is important because both dimensions contribute to subjective well-being (Diener et al., 2018), so knowledge about how they are related to trust and social orientations and whether the same patterns of results can be obtained for constructs representing positive and negative emotional states can be valuable for future investigations.

In the present study we expected that the more altruistic the orientation in participants of the study would be, the higher would be the level of happiness and the lower the level of distress evoked by the pandemic – but only in the case of individuals with high trust (consistent with previous findings showing the role of trust in moderating relationship between wellbeing and SVOs – Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020 – and with research indicating that trust is vital for successful coping with the pandemic – Helliwell et al., 2021). We also hypothesized that the infection can alter otherwise beneficial effects of altruism and trust on COVID-19 stress and happiness, as it is related to higher risk of mental problems (Bourmistrova et al., 2022; Zajenkowska et al., 2023), and prevents social contacts and acting for the benefit of others; thus being an altruistic and trustful person may even increase distress when infected.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

An a priori power analysis conducted in G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) indicated that 270 participants were needed to detect a small effect size (α = .05) with a power of 0.80, but we wanted to maximize the chances of including people who were infected with COVID-19 in the sample, so we decided to enrol more participants. The study was conducted in June 2021 after the end of the third wave of COVID-19. Respondents were all recruited online via one of the biggest research platforms in Poland. The final sample consisted of 405 individuals (180 women, 44%), aged 18-60 (M = 38.91, SD = 11.02). Questionnaires were completed in the following order: Subjective Happiness Scale, Generalized Trust Scale, survey about COVID-19, SVO. A few more measures were used (to assess positive orientation, social well-being, volunteering experience, agency-communion dimension), but for the purpose of this paper only the above-mentioned instruments were included in the analysis. Participation in the study was voluntary and rewarded by credit points that could be exchanged on a research platform for small gifts. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all participants were informed of the anonymity of their responses. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

MEASURES

Happiness. To assess happiness, we used the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999). It consists of four statements describing subjective feelings about one’s own happiness (such as “In general, I consider myself…” 1 – not a very happy person to 7 – a very happy person). The reliability of the scale was good (see Table 1 for Cronbach’s α of measures). The Polish version of the scale was used in the previous studies (Jasielska, 2020; Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020; Jasielska et al., 2021). Prior to the use, the scale was translated into Polish and back-translated by a bilingual person.

Table 1

Zero-order correlations (Pearson coefficients) between study variables, and means, standard deviations, and reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) for continuous variables

Trust. To measure trust, we used the Generalized Trust Scale (Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994). This instrument consists of six statements, such as “Most people are trustworthy”. Participants responded using a 5-point scale. The reliability of the scale was very good. The Polish version of the scale was used in the previous studies and validated in cross-cultural settings (Jasielska et al., 2021). Prior to the use, the scale was translated into Polish and back-translated by a bilingual person.

COVID-19 distress. For the purpose of this study several questions were asked about the participants’ experiences with the coronavirus pandemic. They stated whether they had been infected with COVID-19 and assessed the severity of the disease on a scale from 1 (very light) to 10 (very severe). They were also asked three questions that formed the COVID-19 distress scale – to what extent the pandemic affected 1) their everyday mood, 2) their level of stress, 3) their level of sadness. Participants answered on a scale from 1 (had no influence at all) to 10 (had a very big influence). The reliability of the scale was very good.

Social value orientation. To measure the social value orientation (SVO) we used a slider measure (Murphy et al., 2011) to assess the magnitude of concern that one has for others. In this instrument participants respond to six items where they have to decide about allocation of money between them and another person choosing one from the given options (for example You $50, Other $100). The decision maker (DM) marks the preference on a slider. Answers are coded on a continuous scale from competitiveness (maximum proself) to altruism (maximum prosocial). In previous studies the slider measure had very good convergent and predictive validity and test-retest reliability (Murphy et al., 2011; Pletzer et al., 2018). The Polish version of the scale was used in the previous studies (Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020). Prior to the use, the scale was translated into Polish and back-translated by a bilingual person.

RESULTS

Less than half of the participants had been diagnosed with COVID-19, N = 169 (42%) but only 4 of them had been hospitalized due to infection. Participants rated the symptoms as moderately severe, M = 4.51, SD = 1.52.

Analysis of zero-order correlations (coefficients are presented in Table 1) between study variables showed that women experienced more intensive distress due to COVID. However, COVID-19 distress was also negatively related to trust and happiness.

Hypotheses were tested using the PROCESS procedure for SPSS version 3.4.1. (Hayes, 2018) and SPSS 26 for Windows. The moderated moderation model was tested, in which COVID-19 distress was included as the predicted variable and altruism as the predictor variable. Trust and experiencing COVID-19 infection were moderators, wherein COVID-19 infection moderated the altruism–distress relationship, and trust shaped the COVID-19 infection × altruism interaction. We also included gender as a covariate as it was related to COVID-19 distress. Continuous variables were centred. Model coefficients are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Unstandardized coefficients for the moderated moderation model predicting COVID distress based on altruism, COVID infection, trust and their interactions controlled for gender

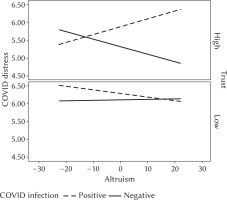

Variables included in the model predicted significant amount of variance in COVID-19 distress, R2 = .09, F(7, 396) = 4.74, p < .001. Gender was negatively related to distress (women felt more COVID-19 distress than men). Also, the altruism × infection × trust interaction was significant. The altruism × infection interaction was significant in participants with high trust, B = –4.33, F(1, 396) = 8.80, p = .003, but not significant in those who were low on trust, B = 1.13, F(1, 396) = 0.65 p = .419. Further analysis of the simple effects of the significant 2-way interaction showed that the relationship between altruism and distress was positive, although not significant (though close to the significance threshold of p < .05) in infected participants with high trust (+1SD, M = 0.77), B = 2.21, SE = 1.17, t = 1.89, p = .059, 95% CI [–0.08; 4.51], but was negative and significant in those who did not experience infection and had high trust. In those who had not experienced COVID-19, altruism was negatively related to distress but only when they also had high trust, B = –2.12, SE = 0.87, t = –2.44, p = .015, 95% CI [–3.82; –0.41]. Slopes for low vs. high trust and COVID-19 infection are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The effect of altruism on COVID-19 distress dependent on levels of trust in people who have experienced vs. have not experienced COVID-19 infection

We also tested a second model for happiness measured with SHS, with the same predictors as for COVID-19 distress (excluding gender as it was not related to any of the variables). Although the model predicted a significant amount of variance in happiness, R2 = .17, F(7, 397) = 11.35, p < .001, only the main effect of trust on happiness was observed, B = 0.64, SE = 0.26, t = 2.40, p = .016, 95% CI [0.11; 1.16]. No other variables or interactions were significant predictors of happiness.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to investigate to what extent a positive attitude towards others expressed as being trustful and showing an altruistic orientation is linked to experiencing distress related to the pandemic. We expected that levels of COVID-19 distress would be lower in participants who were focused on benefitting others and at the same time believed that in general people were trustworthy – provided they had not been infected with COVID-19. Since going through COVID-19 is related to elevated risk of mental problems (Bourmistrova et al., 2022), we assumed that infection can alter positive effects of altruism on COVID-19 distress. Finally, we expected that analogous results would be obtained for happiness, as previous studies had indicated a relationship between altruistic social orientation and happiness among highly trustful subjects (Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020), so we intended to check whether this pattern remained stable during the pandemic.

We found that women declared themselves to be more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than men (their levels of distress were higher). This result was consistent with previous data indicating that women were more prone to feel stress related to the pandemic (Dębowska et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Rey et al., 2020). The level of COVID-19 distress was also negatively related to happiness, which supported the previous findings (Greyling et al., 2020) indicating that the response to the pandemic and stress experienced due to the lock-down and other constraints affect the general well-being (Espinosa et al., 2022; Greyling et al., 2020) or (since these data cannot imply causality) that less happy individuals may be more prone to experiencing stress due to the pandemic.

Consistent with the hypothesis, in non-infected participants with a high level of trust, the relationship between an altruistic social orientation and COVID-19 distress was significant – the more they were willing to benefit others, the smaller the amount of distress they felt. Interestingly, none of these variables separately explained the level of COVID-19 distress in the model – they were significant only when combined together. This implies that another mechanism might exist that explains the results. Studies provide evidence that the feeling of belonging and affiliation is an important factor in creating prosocial attitudes (Okruszek et al., 2020). Perhaps people who are trustful and declare having more altruistic social orientations are more likely to establish social contacts and, as a result, have stronger interpersonal bonds. The fulfilment of the need to belong buffers the negative effects of COVID-19 distress that result from loneliness (Okruszek et al., 2020). Perceived social support was also negatively linked to loneliness during the COVID-19 lock-down (Nowakowska, 2020). This would explain why for the infected participants with a high level of trust the reverse results were obtained – the greater the altruism, the higher the level of COVID-19 distress (this effect was not statistically significant but close to the significance threshold, which suggests that it is worth further consideration). It is likely that, because of the infection and imposed isolation, these others-oriented participants felt lonely. In previous studies, loneliness was linked to heightened anxiety and depressive symptoms and to increased worry about social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic (Okruszek et al., 2020). Since the trustful and prosocially oriented individuals infected with COVID-19 were not able to fully engage in social contacts and help or support others, it might have impacted their level of distress, preventing them from expressing their tendencies. As research has shown, one of the most effective strategies of coping with stress evoked by COVID-19 is seeking emotional support (Babicka-Wirkus et al., 2021). Therefore, the trustful and other-oriented people could suffer the most from being deprived of the interactions based on positive exchange with others, which happened due to regulations imposing social distancing. Hence, in the case of this specific group, when there was no space for acting for the benefit of others, high trust combined with altruistic social orientation could intensify the level of stress instead of buffering it.

We were also interested whether the same pattern of results would be obtained for the indicators of stress and positive emotionality. Analyses have shown that none of the variables (or interaction of variables) except for trust were related to the level of happiness. This result may come as a surprise given the previous data about the links between prosocial behaviour and subjective well-being (Ng & Diener, 2022). Perhaps prosocial orientation denotes a different, more cognitive aspect of prosocial disposition than the actual behaviour measured in the previous studies. Future research would benefit from assessing both a declared orientation towards others and actual activity. Nevertheless, the obtained results confirm the importance of high trust in difficult times and its crucial role in explaining the level of happiness during the COVID-19 pandemic (Helliwell et al., 2021), perhaps strong enough to diminish the value of other potentially relevant factors.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The study has several limitations which ought to be taken into consideration while interpreting the results. Firstly, its cross-sectional character prevents us from establishing any causal relationships. Secondly, the method of recruiting participants, although it enabled us to gather a relatively demographically diverse sample, did not make it possible to achieve representativeness for the national population or to avoid self-selection bias (only members of the research panel could take part in the study). Thirdly, online survey and self-report instruments (including newly created questions, as for COVID-19 distress) were used; thus, we need to acknowledge that the results may have been affected by social desirability bias and the fact of not being controlled by a pollster, as it is in paper-pencil surveying. Also, the results should be considered specific to the context of the period of coming out from a lock-down (June 2021) and an ongoing vaccination programme in Poland. The topic is worth considering in future studies, with more complex or altered models predicting COVID-19-related outcomes. Methodological approaches making it possible to gain deeper insights into the well-being or distress of the participants (e.g. diary studies, interviews) or to explore situational dynamics of feelings (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) would be of value for further investigations in this area. It would also be beneficial to control the target of prosocial behaviour (ingroup vs. outgroup) as there might be substantial differences regarding expressing concern for these two categories (Zagefka, 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

People who have experienced COVID-19 can suffer from distress differently than people who have not been affected. Personal inclinations toward caring for others (altruistic SVO) and interpreting their behaviours (trust) can serve as important factors for understanding these differences. Social distancing, characteristic for the COVID-19 pandemic, generally limits the possibilities to interact with others. When experiencing the disease personally, people are cut off from others even more severely. Although people with a positive orientation towards others (altruistic SVO and trust) can experience less COVID-19-related distress if they have not suffered from this disease, those who are positively oriented towards others and have suffered from COVID-19 (and therefore experienced illness-related isolation) might be more prone to distress. Irrespective of the progress in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, other global health crises are likely to occur. Hence, knowledge about how different aspects of social behaviour are related to pandemic-based distress and wellbeing seems to be vital for supporting societies and individuals in preserving mental health during the next virus outbreaks.