BACKGROUND

In the three southern border provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat, and four districts of Songkla (Chana, Thepha, Saba Yoi and Na Thawi), the population was about 2.2 million with 85.42% practicing Muslims and 14.58% Buddhists and others (Isranews Agency, 2017, March 7). Muslims have freedom to practice their faith. For example, a lot of mosques have been established in response to increasing growth of the Muslim population. At present there are 2,165 mosques in those provinces and districts while there are 292 temples. Females wear headscarves in every social context without exception (e.g., a nurse in a hospital, an airhostess in an airplane). Children are allowed to study in local Islamic schools, which outnumber government public schools in 4 troubled southern provinces. Also, during school periods, students are permitted to leave for praying. Islamic public holidays are officially stated. In addition, Thais’ known personality traits are easy going, with an easy smile, and friendly. They company those traits with Buddhist teaching, particularly impermanent (happiness or suffering), softening strong emotions, and the law of karma. As such, Buddhists and Muslims get along well despite contrasting beliefs in religious practice and lifestyles. However, the gap of intergroup relations has widened from the unrest which caused almost 10 thousand deaths from both Thai Buddhists and Muslims since 2003. This study examined the variables which relate to intergroup attitudes which directly affect intergroup relations.

People belong to different groups. The distinction among different groups builds intergroup attitudes. Intergroup attitudes are beliefs or perceptions among groups with evaluative judgement varying from being relatively neutral to being strongly negative or positive (Kurdi et al., 2019). Intergroup attitudes and beliefs can have a powerful influence on how different groups interact with each other. Many studies on intergroup attitudes have shown evidence on bias reduction between ingroups and outgroups with different approaches. These are intergroup contacts (Ganesan & Carter-Sowell, 2021), perspective taking (Oh et al., 2016), and multiple categorization application (Prati et al., 2016). Cross friendship occurs when they are affiliated with the same social identity characteristics (Boin et al., 2020) such as religion, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, political ideologies, or gender. The application of a multiple categorization approach is based on this research evidence. However, this research extended multiple social categorizations to multiple personality categorization on intergroup attitudes. According to the similarity hypothesis, the more similar two persons are to each other, the more they tend to like each other (e.g., Byrne, 1961; Schachter, 1951). Newcomb (1956) found that similar attitudes predicted subsequent liking between students. Thus, people who have similar personality traits tend to like each other even though they do not share the same social identity (e.g., career, religion, race, university). By having an individual indicate shared personality traits, he or she would recognize similarity. Cross-categorization or recategorization (we-ness) is built, thus supporting an intergroup relationship.

MULTIPLE PERSONALITY CATEGORIZATION

Multiple personality categorization consists of ways to classify multiple personality traits the same manners of categorizing people according to their social identity (e.g., career, gender, race, religion beliefs). Cattell (1947) defined traits as relatively permanent reaction tendencies that are the basic structural units of the personality. Traits are classified in several ways such as central traits and secondary traits. Central traits are the most descriptive trait of an individual’s personality such as intelligent, outgoing, and honest. Secondary traits are traits that a person may display inconspicuously and inconsistently or weakly that only a close friend would notice (Allport, 1937).

Social categorization, social identity theory and self-identification are fundamental foundations of perceived self in people. Social identity influences their thinking, beliefs, and emotions. The way individuals identify with their social identities produces an ingroup and outgroup, leading to a tendency for prejudice and negative intergroup attitudes (Allport, 1954). Most people like to use automatic thinking whenever possible. They are familiar with heuristic thinking. Even though this mental short cut works well, it is ineffective in forming an impression on outgroups. Fortunately, the human brain has the capacity of handling large amounts of information (Crisp & Meleady, 2012). This capacity leads people to think deliberately or elaborately (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), which involves acknowledging and recognizing human diversity as well as multiple personality categorization.

When input of the brain contains approximately four characteristics (categories) of any information including outgroups, perceptions of salience category between groups occur, stimulating the perception of heterogeneity identities among outgroups (Vanbeselaere, 1987). In other words, the brain process proceeds to decategorization on multiple categories inputs, enhancing individuation, which reduces stereotypes (Hutter et al., 2009, 2013) and increases multiple category perception. Conversely, when the human brain relies on few data, the perception of homogeneity increases, disrupting diversity (Halford et al., 2005). Multiple category perception helps promote a change in category-based bias cognition and facilitates healthy outgroup judgment (Albarello & Rubini, 2012; Crisp et al., 2001). Overall, through the window of multiple personality perception, the impression of individuation or decategorization is formed.

PERSONAL VALUES

Values are among the variables that affect individual bias in different situations. They act like a human compass for decision-making, choice, behavior (Cohrs et al., 2005) and perception (Gandal et al., 2005; Schwartz, 1992). That is, they guide people’s attitudes and behavior towards outgroup members explicitly or implicitly. Personal value variables have been explored in many studies such as on attitudes towards migration (Davidov et al., 2008), on readiness for outgroup social contact (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000), on interpersonal feelings such as feeling guilty, a sense of shame (Silfver et al., 2008), on moral reasoning (Myyrya et al., 2010), and on intragroup and intergroup empathy (Zibenberg & Kupermintz, 2016). Specifically, equality or egalitarian values were associated with admiration for outgroups (Biernat et al., 1996), while authoritarian (authoritarianism) values and strong religious beliefs were correlated with intergroup bias (Altemeyer, 1998). In addition, school values of compliance and dominance were correlated with student violence, and harmony values were linked to student support (Daniel et al., 2013). In summary, strong links between personal values and intergroup attitudes are found.

There were also associations between personal values and personality traits. Research has found the relationship between personality traits of the Big Five (neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience and conscientiousness) and personal values (Roccas et al., 2002). De Raad and Barelds (2008) and Roccas et al. (2002) found positive correlations between agreeableness and personal values of benevolence, conformity, and tradition. Negative correlations were found with the power value. Extraversion was found positively related to the stimulation, hedonism, and achievement values, and negatively related to the tradition value (Roccas et al., 2002).

From the research evidence of the personal values-intergroup attitudes link and the personal values-personality traits link, we speculate that personal values can affect the association between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes. Thus, personal values were hypothesized as a moderator between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes. In this study, universal values (e.g., equality, social justice) and conservative (e.g., humble, holding to religious belief) were specified as personal values.

SOCIAL IDENTITY COMPLEXITY

Social identity complexity (Roccas & Brewer, 2002) refers to the degree of individual perceived membership in heterogeneous categories (e.g., gender, religion, ethnicity, happiness). The more overlap on different perceived social categories, the higher is social identity complexity. That is, the individual is inclined to wear many hats since he/she has identified with many different social categories. This increases the chance of overlaps in outgroups’ social categories similarity. For example, suppose A identified himself as a doctor, graduated from X university, loved football and traveling and identified with four social categories and subjectively perceived only those who possessed all four categories as we-ness. In this scenario, he had low social identity complexity. But if he allowed those who possessed only one or two correspondent categories to be his we-ness (e.g., we love football), the intergroup relationship becomes wider and open to more contact. Social identity complexity was also found to correlate with outgroup tolerance (Brewer & Pierce, 2005), low susceptibility to normative influences (Orth & Kahle, 2008), and need for cognition (Miller et al., 2009). Also, social identity complexity is a mediator between interactions and attitudes with the outgroup (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014). In this study, social identity complexity is explored as a mediator between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes.

THE CURRENT RESEARCH

This study investigated whether the perception of the multiple personality categorization affects intergroup attitudes among Thai Buddhist and Muslim college students in the troubled southern provinces of Thailand through mediators and moderators of social identity complexity and personal values respectively. Research on intergroup attitudes, social identity complexity, and personal values among college students in the southern university has an important implication. The results can provide extensive information on those variables among Thai Buddhist and Muslim young generations amid the unrest.

Recent research on the categorization approach for bias reduction has all been focused on the multiple social category or multiple category (Prati et al., 2016). This study has modified the multiple social category concept and specified the multiple personality category in which the subjective traits of the ingroup are perceived in those of the outgroup as well. This rationale is based on the idea that shared social identity among the ingroup and outgroup is a loose WE group. The most cohesive groups were those with feelings of trust (Corey et al., 2014). The concept of the multiple personality category is inferred from projection of the defense mechanism in which individuals avoid unaccepted traits, desires, and needs by perceiving those belonging to others. If individuals are required to indicate their traits which correspond to others, they are supposed to acknowledge the WE group of shared traits, substituting THEM (not US). The multiple personality categorization among Buddhists and Muslims in Thailand has not been examined. Will multiple personality categorization be effective for decreasing group biases? To date, the effect of social identity categorization on intergroup relation has been tested (Hutter & Crisp, 2006; Vasiljevic & Crisp, 2013), but no study has addressed the impact of multiple personality categorization on intergroup bias. If the answer is “yes”, what are those shared personality identities? Study 1 was conducted to answer this question. The study explored the aspects of shared multiple personality traits perceived between Buddhist and Muslim students. Study 2 was performed to assess the impact of multiple personality categorization on intergroup attitudes. The study explored the new scores of multiple personality categorization between Buddhist and Muslim students as well as those on social identity complexity, and on personal values in universalism and conservative (tradition). Social identity complexity was used as a mediator between cross-ethnic friendships and ethnic outgroup distance (Knifsend & Juvonen, 2014). In Study 2, it was also a mediator but between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes. Personal values (universalism, benevolence, and power, achievement) were studied as variables that had a direct impact on intergroup empathy (Zibenberg & Kupermintz, 2016). In this model, personal values of universalism and tradition were moderators between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes.

STUDY 1

The Prince of Songkla University Pattani campus is located in Pattani province, which is one of the five southern border provinces of Thailand. This is an area of unrest where violence has happened intermittently. The levels of severity have been higher since 2004 (Deep South Watch, 2022). Student populations are Muslims (95%) and Thai Buddhists (5%). This study examined multiple personality category perceptions among Buddhist and Muslim students living in the troubled southern provinces. The objective is to obtain a list of personality traits that both groups perceive identically.

Research question: What are the top ten personality traits that both Muslims and Thai Buddhists perceive correspondingly?

Perceived personality traits outgroup refers to 1) Buddhists’ perceptions of Muslim shared traits, and 2) Muslims’ perceptions of Buddhist shared traits. Hopefully, traits shared that are reported highly and lowly would lead to future application.

PARTICIPANTS

Simple random sampling consisted of 382 university students. Participants were Muslim (65.4%), Buddhist (34.6%), female (78.8%), male (21.2%), with average age of 20.15 years (SD = 1.01). The average length of stay in the southern border provinces for Buddhist and Muslim students was 5.70 years (SD = 6.86) and 15.06 years (SD = 7.80) respectively.

MEASURES

Multiple personality category (MPC). We found that Anderson’s (1968) personality-trait words was one of the most comprehensive personality trait measurements. All the words of the 555 Anderson personality trait words were translated into Thai. Then, all synonymous Thai words were recategorized as one category, yielding a total of 172 traits in the Thai context. All 172 traits were rated on shared perceptions between Buddhist and Muslim students.

The sample took the multiple personality categorization (MPC) perception scale of 172 items to assess outgroup perceived personality. Muslim participants responded to the question: “How do you rate your scores on the following traits you perceive in Thai Buddhists?” Vice versa, Buddhist participants rated their version on Muslims. The scores ranged from 0 (not perceived at all) to 6 (perceived the most). The statistical analysis was based on the mean.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Data were analyzed using SPSS. The descriptive statistics of mean, standard deviation and independent t-tests were computed.

RESULTS

The top ten scores of shared identical personality trait of outgroups among Buddhists and Muslims were creative, smart, objective, talented, generous, kind, curious, resourceful, serious, and skeptical (Table 1). All nine traits rated were scored higher for Buddhists except serious traits. The seven traits that were significantly higher for the Buddhist group were creative, smart, generous, resourceful, talented, kind, and curious.

Table 1

Mean, standard deviation, and independent t-tests in personality traits of participants

STUDY 2

Study 2 evaluated mediated social identity complexity and moderated personal value in association between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes. To achieve the accurate rational cognition on heterogeneity of out-groups, more social cognition of the elaborate thinking system is necessary for assessing social identity complexity.

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were 150 volunteer students at Prince of Songkla University, Pattani campus, who were residents in three southern border provinces for at least two years. They were Thai Muslims (66.7%), Buddhists (33.3%), females (89.3%), males (10.7%), with average age of 20.31 years (SD = 0.94). Their average time spent in southern border provinces was 11.90 years (SD = 8.97).

DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURE

The participants took about 20 minutes to finish four scales of multiple personality categorization: short version, intergroup attitudes (IA), social identity complexity (SIC), and personal values (PV).

MEASURES

Multiple personality categorization: short version (MPCS). MPCS was developed from multiple personality categorization of 172 trait words used in Study 1. The scale consisted of the top ten perceived shared traits among 172 attributes between Thai Buddhists and Thai Muslims (e.g., creative, smart, talented). The ten traits were rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree about correspondent traits between Thai Muslims and Thai Buddhists) to 7 (strongly agree). The α reliability coefficient for the MPCS in the present study was .88. MPCS mean scores of the top 10 shared traits between Thai Buddhists and Thai Muslims, ranking from the highest to the lowest among 172 traits from MPC, are shown in Table 1.

Intergroup attitudes scale (IA). Items assess the degree to which Muslim/Thai Buddhist students wanted to associate with ethnic out-group members. The scale was adapted from Hutchison and Rosenthal (2011) on the combination of outgroup attitudes (e.g., “I like Muslims/Thai Buddhists”; “I prefer to spend time with Muslims/Thai Buddhists than Thai Buddhist/Muslims”), intergroup behavioral intentions (e.g., “I would help a Muslim/a Thai Buddhist if he or she was being discriminated against”), and intergroup anxiety (e.g., “I feel anxious/nervous when I come into contact with Muslims/Thai Buddhists”). Participants rated 10 items of the outgroup on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Scores were reversed on items indicating negative attitudes. A higher score represents positive intergroup attitudes. In this sample, the Cronbach’s α of the IA scale was .75. Higher scores mean more positive intergroup attitudes in cognition, feelings and behaviors toward the outgroup.

Social identity complexity (SIC). Four items assessing the degree to which two in-groups overlapped were used to calculate social identity complexity. The scale was adapted from social identity complexity, an adult version, by Brewer and Pierce (2005), and an adolescent version by Knifsend and Juvonen (2014). First, we oriented participants to social identity groups by religion or ethnicity, and gave examples of other group categories (e.g., college students, Thai southerners/northerners, cat/flea market lovers). Then, they were asked to describe themselves according to (a) favorite food, (b) sibling order by completing two incomplete sentences (“My favorite food is…”; “I am the… in family”). These two categories were personally meaningful since they resulted from the survey conducted on pilots’ participants, yielding the top two public self as identifying with favorite food and sibling order. Next, participants were requested to provide their answers on each bidirectional pairing of two groupings (e.g., “How many Muslims like (name food)?”; “How many persons who like (name food) are Muslims?”) on a 5-point scale from 1 (almost all) to 5 (hardly any). Participants then rated the 2 pairings of their own social ingroups on the same 5-point scale. Social identity complexity scores were calculated as the mean of the 4 ratings reflecting the overlap of the 4 groups listed. In this sample, the Cronbach’s α of the SIC scale was .64. High score means more complex of social identity, i.e. a person is characterized by holding many social identities in different groups.

Personal values (PV). The scale was derived from a shortened version of Schwartz’s Value Survey (SVS; Lindeman & Verkasalo, 2005) on universal and tradition values. For each value, respondents rate its importance as a life-guiding principle for him/her on the 8-point scale. 0, 1, 4, and 8 on the scale indicate that the value is opposed, not important, important, and of supreme importance to his/her principles respectively. Eight items measured universalism values (e.g., broad mindedness, social justice, equality). Five items measured tradition (e.g., humbleness, devotion). The α reliability coefficient was .91. Personal values refers to 13-item scores on the Personal Value Scale developed by Schwartz (1992). High scores mean high personal values on both universal and conservative values.

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the studies’ variables are reported in Table 2. The analysis revealed significant positive associations between multiple personality categorization, intergroup attitudes, personal values, and social identity complexity. Intergroup attitudes were significantly related to personal values, but not to social identity complexity.

Table 2

Mean, standard deviations, and correlation for study variables

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS AMOS. Structural equation modeling (SEM) procedures using maximum likelihood estimation were conducted to examine the research hypotheses regarding the multiple personality category on Buddhist-Muslim intergroup attitudes by moderating personal values and mediating social identity complexity. To evaluate the overall fit of the model to the data, several indices recommended by Kline (2011) were calculated in the present study: chi-square statistic (χ2), χ2/df ratio, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). According to Kline (2011), goodness-of-fit criteria were used in the current study that acknowledged the potential for acceptable (χ2/df ratio < 3, GFI, CFI and TLI > .90, SRMR < .10, RMSEA < .08) and excellent fit (χ2/df ratio < 2, CFI and TLI > .95, SRMR < .08, RMSEA < .06).

RESULTS

This analytical model tested for the moderation effect of personal values and the mediation effect of social identity complexity of the association between multiple personality category and intergroup attitudes. The goodness-of-fit indices of the hypothesized direct effect moderation model were χ2(2) = 2.10, χ2/df = 1.05, p = .350, GFI = .994, CFI = .998, TLI = .992, SRMR = .028, RMSEA = .018.

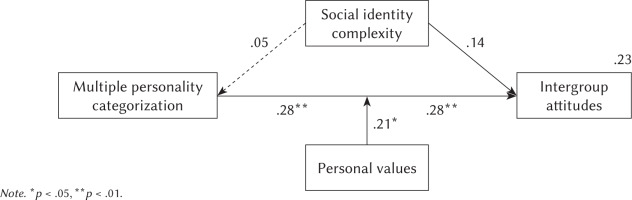

Figure 1 and Table 3 shows that multiple personality category had a positive association with intergroup attitudes (β = .28, p < .001), indicating that perceiving more multiple personality category of outgroup is related to higher intergroup attitudes. Social complexity was positively associated with intergroup attitudes (β = .14, p = .056), whereas it was not significantly associated with multiple personality category. Further, personal values had a positive direct effect on intergroup attitudes (β = .21, p = .007). In addition, the interaction effect between multiple personality and personal values was significant (β = .28, p < .001). To summarize, the results showed that the multiple personality category, personal values, and social identity complexity were directly related to intergroup attitude. Personal values successfully functioned as a moderator.

Figure 1

The structural equation model regarding the moderating effect of personal values and mediating effect of social identity complexity on the association between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes

Table 3

Moderated mediation analysis of variables

| Variables | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| MPC → IA | 28*** | .06 | 3.53 | < .001 | -1.56 | -0.31 |

| MPC → SIC | .05 | .02 | 0.56 | .576 | -0.03 | 0.05 |

| SIC → IA | .14* | .23 | 1.91 | .056 | -0.02 | 0.88 |

| PV → IA | .21** | .03 | 2.68 | .007 | -0.69 | -0.16 |

| MPC*PV → IA | 28*** | .38 | 3.80 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| R2 | .23 | |||||

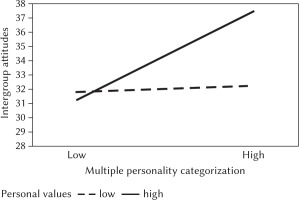

The effects of multiple personality categorization on intergroup attitudes were examined by a simple main effects analysis at 1 SD above and below the mean of personal values. At the high level (mean + 1 SD) of personal values, the main effect of high multiple personality categorization was significant. The higher level of multiple personality categorization was related to a high level of intergroup attitudes (β = .48, p < .001). The low level (mean – 1 SD) of personal values gave a constant line and was not significant (β = .03, p = .712). When the multiple personality categorization increased, the intergroup attitudes level was unchanged. High levels of multiple personality categorization were significantly associated with a high level of intergroup attitude at a high level (mean + 1 SD) of personal value. When compared with a low level of personal values, the high level of personal values gave a higher slope. Figure 2 depicts multiple personality categorization moderated by personal values.

Figure 2

Moderating effect. Personal values moderate the relationship between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes among Buddhist and Muslim students

To evaluate the conditional indirect effects of the level of multiple personality categorization on intergroup attitudes via personal values as a moderator with different ranges, indirect effects at three levels of personal values (1 SD above the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD below the mean) were examined using the 95% CI of the bootstrap method. As shown in Table 4, the conditional indirect effect on intergroup attitudes arose from multiple personality categorization via personal values. This effect changed according to the range of the personal values and was weakest at 1 SD below the mean of the personal values. These results indicated that the more multiple personality categorization Buddhist and Muslim students had, the more positive intergroup attitudes they developed. To conclude, Buddhist and Muslim students who were high on personal values and multiple personality categorization could achieve better intergroup attitudes than those with low levels of both personal values and multiple personality categorization. Buddhist and Muslim students who were in the low range of personal values had low scores on intergroup attitudes, but high scores on multiple personality categorization.

DISCUSSION

Social psychologists have developed many techniques in an attempt to reduce bias across groups. Recategorization is among those. This process is based on the ingroup identity model (Gaertner et al., 1993; Riek et al., 2010) to the extent that when individuals of different social groups come to perceive themselves as members of a single social entity, their attitudes toward each other become more positive. Since the “us” and “them” categorical distinction often produces prejudice, when “them” become “us”, positive intergroup attitudes will increase.

The power of shifting to a more inclusive category for positive attitudes toward an outgroup has been shown in many studies (Albarello & Rubini, 2012; Wohl & Branscombe, 2005). Most previous studies have focused predominantly on the inclusive social identity (e.g., gender, citizen, etc.). This study sought to move beyond tradition social categorization by extending multiple social categorizations to multiple personality categorization. This inference is based on the mechanism of projection in which individuals perceive socially unacceptable traits or desire in others. By having individuals examine their personality traits which they see in the other outgroup, the “us”/“them” categorical distinction is diminished. To contribute to and extend the interplay between multiple social categorization and bias, the present study aimed to investigate the role of multiple personality categorization in intergroup attitudes through the mediation of personal values, and social identity complexity as a mediator.

Study 1 surveyed the shared identical personality traits of both the ingroup and outgroup among Thai Buddhist and Muslim university students in a southern province where intergroup attitudes among people seem unfavorable. A 172-trait list was developed from the Anderson (1968) personality scale. The top ten highest ratings of identical traits perceived by both groups were: creative, smart, objective, talented, generous, kind, curious, resourceful, serious, and skeptical. Interestingly, Muslim students’ scores for Buddhists on shared traits (creative, smart, generous, resourceful) were higher than those scores of Buddhists on Muslims. Though Muslim students are a majority on campus, they are a minority in Thai society and are exposed to culture, songs, movies, or media that mostly portray Thai Buddhist stories. By contrast, Buddhist students receive a picture of more Muslim violence in southern unrest.

Study 2 explored a model of the relationship between multiple personality categorization, intergroup social identity complexity, and intergroup attitudes via a mediated moderation analysis. Our results revealed a positive correlation between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes among Muslim and Buddhist students. Priming Thai Buddhist and Muslim students who belong to different groups to perceive themselves as sharing several positive traits could shift the boundary between “us” and “them”. Through addressing multiple personality categories, the personal identity was emphasized and downplayed group identity, which helped buffer outgroup stereotypes. This is generally consistent with the findings that multiple social categorizations were linked to changing stereotypes (Prati et al., 2016). It made little sense to compare oneself with the outgroup, thus fostering intergroup attitudes. However, multiple personality categorization did not have an indirect effect on intergroup attitudes via social identity complexity mediation. In other words, social identity complexity does not mediate the effect of multiple personality categorization on intergroup attitude. The result might be attributed to the fact that the scores derived from social identity complexity were not accurately addressed by the values measured. That is, the respondents failed to discriminate the overlap between the two in-groups from bidirectional pairing, although the scale was adapted from social identity complexity by Brewer and Pierce (2005), and by Knifsend and Juvonen (2014) which has acceptable psychometric properties in terms of dimensionality and internal consistency. In this study, the scale was composed of questions with perplexing structure, featuring comprehensive difficulty of sets of pair questions. To elaborate, one set of pair questions addressed different levels of critical thinking consecutively. The second question required much more time to meet cognitive sophistication or a higher level of critical thinking than the first one. Example, 1. How many Muslims like (name food)? 2. How many persons who like (name food) are Muslims? Respondents may not be willing to perform these pair processes thoroughly and accurately (Krosnick, 1991), particularly after they have been primed to use little effort in cognitive endeavor on two previous scales: multiple personality categorization (short version), and intergroup attitudes scale (Meyers-Levy, 1989). This results in indiscriminate answers to pair questions leading to increased measurement error and produces lower-quality data. In short, respondents might apply satisficing response strategies on SIC. This is the most important limitation of this study on designing SIC. We suggest that a new design is needed for the assessment of social identity complexity though it did not correspond to the SIC results in Knifsend and Juvonens’ (2014) study.

However, moderation analyses demonstrated that personal values (universalism and tradition) moderated the strength of the relationship between multiple personality categorization and intergroup attitudes. As seen in Figure 2, the results showed that a low level of universalism and tradition values attenuated the relationship between multiple personality category and intergroup attitudes, while the high personal values augmented the relationship. The result supported Schwartz’s (1992) model on personal values that self-transcendence (benevolence and universalism) emphasizes concern for others while self-enhancement (security, conformity and tradition) may diminish empathy towards out-group members to some extent. In addition, the result was consistent with Sagiv and Schwartzs’ (2000) study showing that readiness for social contact with out-group members correlated positively with favoring values of universalism. Overall, the current study’s results are consistent with many studies on the relationship between self-transcendence and conservation values and perception of outgroups (Souchon et al., 2016; Davidov et al., 2008). Items in tradition values from the Short Schwartz’s Value Survey posit respect for tradition, humbleness, accepting one’s portion in life, devotion, and modesty. These characteristics denote expected norms in collective cultures, functioning as desirable for all Thais and Muslims. Particularly, humbleness and modesty in a collective culture have positive connotations inclining one not to make the individual self higher or better than others. As such, it is often expressed in terms of exhortation against an arrogant or haughty attitude and thus may harness negative attitudes to those who are different in socioeconomic aspects to some extent. Also, Buddhism sees humility as a virtue. Buddhist practitioners believe that only a humble mind can lead to the path of enlightenment and liberation (Yu-Hsi, n.d.).

Next, accepting one’s portion in life and devotion to Buddha for Thais and to Allah for Muslims is beneficial to hinder the escalated conflicts between the two groups. That is, the beliefs in destiny from karma and Allah help both groups not to seek revenge from intermittent unrest that sometimes resulted in the deaths of innocent Thais and Muslims. It is not the tradeoff among personal values but rather the favorability of those tradition values in Thai and Muslim culture and universalism that help strengthen intergroup relations.

In summary, the current findings assign primacy to values of universalism and tradition and the multiple personality category over social identity complexity in predicting intergroup attitudes between Thai Buddhist and Muslim students. That is, adopting multiple personality categorization can foster an intergroup attitude among Muslim and Buddhist students. Previous research had shown a reduction in prejudice and negative attitudes through social recategorization (Prati et al., 2015; Paluck & Green, 2009). Thai Buddhist and Muslim students who shared positive multiple traits appear to develop positive intergroup attitudes. In addition, the moderation analyses confirmed the major role of universal and tradition values in regulating the association between multiple personality categories and interpersonal attitudes among Thai Buddhist and Muslim students.

This study has several limitations. The first limitation is the design of SIC as previously mentioned. The difficulty level and clarity of expression of a test item affect the reliability of SIC. Since the test items might be difficult for the group members to understand, it produced scores of low reliability. To remedy this weakness, the items of SIC should be modified to make it easier for respondents to achieve the answer corresponding to a theoretical construct of social identity complex. Also, more items should be added so as to increase its reliability. Secondly, the study should have given more attention to the order of scales handed to participants. The sequence of scales given could affect their answers and consequently the analyses. Thirdly, the sample in this study used students, though they were proportionally random from all faculties in the university. The student sample may interfere with external validity. However, the student sample could be an initial start to explore shared multiple traits between in- and out-groups before extending the research to Thai Buddhists and Muslims in villages, towns, or provinces.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The main contribution of this article is in demonstrating that multiple personality categorization is a variable related to intergroup attitudes. This is the first investigation of multiple personality categorization modified from multiple social identity. The result of Study 1 provided new information on shared multiple traits perceived between Muslim and Buddhist students in troubled southern areas of Thailand. The multiple personality categorization can be used as an alternative variable to foster group cohesion between Thai Buddhist and Muslim students. The results of Study 2 showed a positive correlation between multiple personality categories and intergroup attitudes by the moderating effect of personal values, while it was non-significant through the mediating effect of social identity complexity. Like Study 1, the study may have practical implications for intervention programs that aim to improve intergroup attitudes. We expect that gaining information about the perceptions of one group’s personality towards another will lead to more thoughtful management of problems, for example, the management of trust between different groups in the area, or the cultural activities that require shared space in society. For government policy management, perceiving intergroup personality will help in planning long-term sustainable cooperation which may decrease the risk of ethnic insecurities from personality projection. In other words, the future application of multiple personality categorization will lead to more thoughtful problem-solving in cognitive changes, interventions and policy related to intergroup attitudes among Thai Buddhists and Muslims in troubled southern areas. In short, we suggest multiple personality categorization as a new variable for prejudice reduction together with universalism and tradition values, the latter of which are favorable to the outgroup in collective culture.