BACKGROUND

For more than two years, the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been the most serious health challenge in the world. In addition to its physical health risks, it had a severe impact on the mental and social functioning of people around the world. Fear of infection and its related complications can negatively affect the well-being of many people and contribute to less effective daily and professional functioning (Jasiński et al., 2021). The well-being of many people was influenced by the fear of a previously unknown disease and its possible transfer to the family, the constant uncertainty of the situation and the lack of control over what could happen. Risk perception associated with the disease and the fear of COVID-19 are among the many variables affecting the mental health of people during the current pandemic (Dymecka et al., 2023a). Kondratowicz et al. (2022) found that remote work was related to lower perceived stress and greater job satisfaction among office and industry workers in Poland. However, the effect of COVID-19 risk perception on workers such as teachers, who usually work in-person with bigger groups of people, is not clear. Li and Yu (2022) found in their meta-analysis that for many teachers in the West, work satisfaction deteriorated during COVID-19. The key to understanding the difference between those results may lie in the interplay between the perceived risk of COVID-19 contagion and Polish teachers’ burnout degree (see also Sygit-Kowalkowska, 2023) – a relation that will be analysed in the current paper.

PERCEIVED RISK AND FEAR OF COVID-19

Risk perception is the personal view on vulnerability, the likelihood of getting infected or being at risk of illness (de Zwart et al., 2009). Risk perception is the person’s assessment of how harmful the consequences of the threat would be to the valued objects if the threat occurred. Previous studies indicated that the perceived risk was negatively associated with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic (Krok & Zarzycka, 2020). Since teachers in Poland at the beginning of the second wave of the pandemic worked in-person, they were exposed to a greater risk of infection due to contact with a large number of people (Cori et al., 2020). This may have influenced their subjective chance of becoming infected, which in turn may increase their fear of COVID-19. Outbreaks of contagious diseases such as COVID-19 lead to fear, which can be defined as a state of uneasiness or apprehension that results from the anticipation of a real or perceived threatening event or situation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people were also afraid of serious health complications related to COVID-19, hospitalization and long quarantine, related to themselves and their families. The increased level of fear of COVID-19 may result from the threat and risk perceived by a given person. An additional factor that increases fear is the awareness of having other, coexisting diseases that predispose to a more severe course of COVID-19 (Cori et al., 2020).

TEACHERS’ WORK DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

During the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to healthcare workers, education workers were particularly affected. At first, distance learning methods were introduced in Poland. After loosening the restrictions at the beginning of the 2020/21 school year, many teachers returned to the traditional form of teaching. In September and October 2020, the media reported increasing numbers of infected teachers as well as fatalities. In this professional group, studies observed fear of infecting oneself and transferring a possible disease to the family, which could lead to many negative psychological and social consequences (Dymecka et al., 2023a). New professional challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic could also contribute to work overload and additional stress for teachers (Li & Yu, 2022). The consequence of these symptoms may be a reduction in their well-being, which also translates into functioning in the professional sphere (Dymecka et al., 2023b). Teachers working in-person were more exposed to the disease, and those working remotely were forced to change the style of their work. The need to move to distance learning has left many teachers with additional fears and new responsibilities. All of this could lead to the occurrence of occupational burnout syndrome (Bakker & Demerouti, 2018; Walczak & Vallejo-Martin, 2021).

OCCUPATIONAL BURNOUT

Teachers are a professional group, which is especially at risk of professional burnout (see Sygit-Kowalkowska, 2023). Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal and emotional stressors at work. It is also sometimes defined as a state of fatigue and frustration resulting from dedication to a given activity, case, task or person that did not bring the expected result. Maslach distinguished three components that make up the burnout syndrome (Maslach et al., 2001). The first one is emotional exhaustion, i.e. a feeling of emotional overload, exhaustion, and lack of energy. It is associated with many physical ailments, such as headaches and sleep problems. The second element is depersonalization, i.e. a negative attitude towards colleagues or pupils. It involves treating other people indifferently, impersonally, and even contemptuously. The third component of burnout is the lack of a sense of personal achievement, i.e. a negative assessment of one’s work and professional skills (Tucholska, 2003). All of those aspects of occupational burnout can negatively affect employees’ job satisfaction (Bakker & Demerouti, 2018; Jasiński et al., 2021).

JOB SATISFACTION

Job satisfaction is an emotional reaction of pleasure or burden to the performed professional duties (Loher et al., 1985). It is a fairly stable feeling over time, depending on many variables such as values, individual preferences or experience (Judge et al., 2000). Job satisfaction depends on factors related to professional activity and life outside work (Hulin, 1969). People who feel satisfied with their professional role have a sense of success and positively assess their professional duties. They believe that their work brings joy and allows them to meet their basic psychological needs (Walczak, 2018). A person who is satisfied with their work performs their duties better, more effectively and is more successful at work. Consequently, employee satisfaction is a key element both in terms of personal well-being (Rice et al., 1980), and in the context of the good functioning of the organization (Taris & Scherurs, 2009). When considered as a general emotional evaluation, job satisfaction balances the interplay between the positive and negative properties of one’s current work state (see Walczak & Vallejo-Martin, 2021). Consequently, it is an optimal end measure of affective and environmental work consequences.

THE CURRENT STUDY

During a pandemic, people experience many negative emotions. This leads to an increase in the level of stress (Dymecka et al., 2023b), which is one of the most important causes of occupational burnout (Bakker & Demerouti, 2018). Stress caused by the sense of danger during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with an increased sense of occupational burnout (Jasiński et al., 2021). It can therefore be assumed that the feeling of being at risk of becoming infected during the COVID-19 pandemic can affect the level of teachers’ occupational burnout while lowering their job satisfaction. Research shows that the feeling of danger and fear of infection are negatively associated with life satisfaction (Dymecka et al., 2023a), and people dissatisfied with their life situation have a low level of job satisfaction (Rice et al., 1980). It can therefore be assumed that teachers who are concerned about COVID-19 will be less satisfied with their work. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers experience stress as a result of changing the form of teaching. Not having the right equipment for distance learning, lack of knowledge about modern technologies, as well as the need to meet new requirements cause an increase in the level of stress in many teachers. E-learning requires teachers to spend more time on their work, which can make them feel tired and overloaded. It can be assumed that the need to change education from traditional, direct contact in classrooms to distance contact with the use of technological solutions, as well as the prolonged occurrence of such a situation, may contribute to an increase in the level of occupational burnout.

Job satisfaction and burnout are negatively correlated with each other (Park & Shin, 2020). Studies have shown that all three elements of occupational burnout were mediators between job level and job satisfaction (Kim et al., 2017). During a pandemic, people felt threatened, many people had limited interpersonal contacts, and remote work can lead to a feeling of loneliness, all of which could make them feel emotionally exhausted. As anxiety and insecurity increase, emotional exhaustion increases, leading to less job satisfaction. Moreover, changing working conditions and the lack of personal contact may contribute to depersonalization, which is also associated with the level of job satisfaction (Erdal et al., 2021). Therefore, it can be concluded that occupational burnout can mediate the relationship between fear of COVID-19 and teachers’ job satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

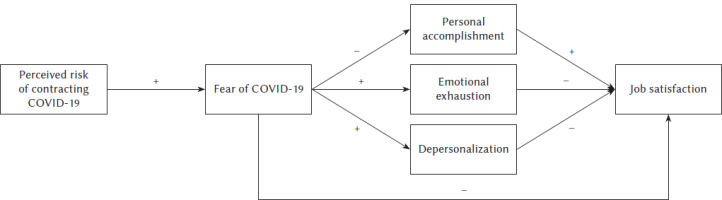

Taking all of the above into consideration, we decided to test the following model of relationships between risk of contracting and fear of COVID-19, occupational burnout and job satisfaction in Polish teachers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

STUDY DESIGN AND PROCEDURE

The presented study was conducted between November 2020 and February 2021. Data collection was done via the Internet due to the prevailing epidemiological situation. Study participants completed surveys using the Google Forms platform. No personal information or email addresses were collected. A link to the survey was posted on social media groups dedicated to teachers and also sent to the secretariats of the selected educational institutions with a request to forward them to teachers working in a given institution. Due to the fact that the study consisted of several questionnaires, all scales were preceded with instructions and a description of each scale. After completing the survey, the respondents were able to express their opinions about the study in which they participated – none of the respondents expressed a negative opinion about the formulated survey. All study participants were informed about the purpose of this study, the anonymity of the survey and that they could discontinue taking part in it at any time without giving any reason. All respondents gave informed consent to participate in this study.

PARTICIPANTS

Three hundred fifty-two teachers (316 women and 36 men), aged between 22 and 68 (M = 43.26, SD = 9.50), participated in this study. Most of the respondents were married teachers, living in cities, working in primary schools and teaching science and humanities-related subjects. In the studied sample, 252 people worked remotely, 41 in-person and 59 were hybrid workers. The preference for remote work was reported by 55% of the respondents. The exact characteristics of the studied sample of Polish teachers are presented in Table S1 in Supplementary materials.

MEASURES

Risk of contracting COVID-19. The Risk of Contracting COVID-19 Scale developed by Krok (2020) was used. It consists of 11 items on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It was developed based on Grothmann and Reusswig’s (2006) concept. It measures participants’ perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 with items such as: “I’m worried that I won’t be able to protect myself from infection”. A higher score on the Risk of Contracting COVID-19 Scale reflects a greater perceived probability of contracting the coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 disease. The questionnaire is characterized by good reliability (in this study, Cronbach’s α = .93).

Fear of COVID-19. The fear of COVID-19 was measured by the Polish FOC-6 scale (Dymecka et al., 2021). It consists of 6 items on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). It measures participants’ perceived fear of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease with items such as: “I am afraid of losing my life due to coronavirus infection”. A higher score on FOC-6 reflects a greater perceived fear of COVID-19. FOC-6 is characterized by good reliability (in this study, Cronbach’s α = .88).

Occupational burnout. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach et al., 1997) adapted by Pasikowski (2000) was used. It consists of 22 items on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). It measures participants’ occupational burnout with items such as “I feel emotionally exhausted because of my work”. It consists of 3 subscales: emotional exhaustion (9 items), depersonalization (5 items), and professional achievement (8 items). A higher score represents the greater intensity of a given sphere. MBI is characterized by good reliability (in this study, Cronbach’s α = .77-.93).

Job satisfaction. The Brief Job Satisfaction Scale (BJSS; Judge et al., 1994, 1998) in the Polish adaptation of Walczak and Derbis (2015) was used. It consists of 5 items on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It measures participants’ perceived job satisfaction with items such as: “I feel fairly well satisfied with my present job”. A higher score on BJSS reflects greater job satisfaction. The presented scale is characterized by good reliability (in this study, Cronbach’s α = .84).

RESULTS

We decided to apply the path analysis approach to verify the hypothetical model. We verified the relationships between the tested variables using Pearson’s r correlation. The analysis showed that the risk of contracting COVID-19 was positively related to fear of COVID-19 and emotional exhaustion. Moreover, fear of COVID-19 was negatively related to personal accomplishment and positively related to emotional exhaustion. Fear of COVID-19 was not significantly correlated with depersonalization and job satisfaction in the studied sample of Polish teachers. Lastly, all three dimensions of occupational burnout were significantly related to job satisfaction. For more detailed information, see Table 1.

In the next step, we decided to analyse the formulated model of the relationships between risk of contracting and fear of COVID-19, occupational burnout and job satisfaction in Polish teachers. The values of skewness and kurtosis did not show large asymmetry in the distributions of the tested variables. Mahalanobis distance (MD) values did not indicate the inclusion of outliers in the model that could affect its properties (see Table 1). On this basis, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method was used to verify the hypothesized model.

Table 1

Results of Pearson’s r correlation, path analysis and sensitivity power analysis (N = 352)

[i] Note. Assumed model fit threshold values – CFI > .950; TLI > .950; SRMR < .080; RMSEA < .060 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). In the alternative model, error covariances were set between burnout subscale errors. Measurement invariance was tested between two groups: teachers who preferred remote work (n = 192) and those who preferred stationary work (n = 160). *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Initially, the model did not achieve an acceptable fit (see Table 1; Hu & Bentler, 1999). To improve its properties, statistically insignificant paths were removed. It did not significantly improve the properties of the tested model. Based on modification indices, error covariances were set between the occupational burnout subscales. After that modification, a good fit was obtained (see Table 1).

An alternative model is presented in Figure 2. The risk of contracting COVID-19 was a positive predictor of fear of COVID-19. There was no direct relationship between fear of COVID-19 and job satisfaction. This relation was mediated by two scales of occupational burnout: personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion. All three subscales of occupational burnout were significant predictors of job satisfaction, explaining 53% of its variance. Emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment were responsible for most of the job satisfaction explained variance. Multicollinearity was not observed in the tested model (see VIF coefficient values in Figure 2).

To verify the versatility of the obtained model, we decided to test whether we could detect any measurement invariance violations (see Gerymski, 2021). Due to the inequality and small sample size in most of the tested potential grouping categories (see Table S1 in Supplementary materials), it was decided to test the model only between two groups: teachers who preferred remote work (n = 192) and those who preferred in-person work (n = 160). The analysis showed that configural, metric and scalar invariance were not violated (see Table 1). It means that the tested model can be interpreted in the same way in both indicated groups.

Lastly, since we did not calculate the required sample size before starting the study, we decided to perform sensitivity power analysis (see Lakens, 2022). While maintaining power at the level of 80%, this study was not able to detect small effect sizes lower than ρ = .15 and ƒ2 = .04 (see Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The current research aimed to verify the model showing the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19, occupational burnout and job satisfaction in Polish teachers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. It also aimed to verify whether individual aspects of burnout play a mediational role between the fear of COVID-19 and job satisfaction.

In our study, the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19 was positively related to fear of COVID-19. This means that our study participants with a greater risk of becoming infected had a greater fear of COVID-19. The risk perception of COVID-19 could be greater in people who assess the probability of infection as higher, which could be associated with more frequent contact with people while performing their professional duties (de Zwart et al., 2009). Fear of COVID-19 could contribute to increased tension, which in turn would develop the occupational burnout syndrome (Erdal et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting changes in teaching have contributed to the high levels of stress, fatigue and exhaustion among teachers (Śliż, 2020). The relationship between fear and burnout has been confirmed in many studies during the COVID-19 pandemic in a group of teachers (Carreon et al., 2021; Westphal et al., 2022). New situations (such as changing an in-person work environment to a remote one) may accumulate with other stressors and lead to exhaustion of a given person, favouring the development of occupational burnout syndrome.

In our study, fear of COVID-19 and depersonalization were not significantly related. This means that teachers who were afraid of the disease did not have a negative attitude towards their environment. Depersonalization in teachers is related to treating students indifferently, impersonally, and distantly (Tucholska, 2003; Park & Shin, 2020). During the pandemic, other variables could have influenced this approach to students, such as distance learning, lack of personal contact or the need to reconcile remote work with home responsibilities. Most likely, these factors could have contributed more to the increase in depersonalization than the fear of infection itself. On the other hand, our study showed a negative correlation between the fear of COVID-19 and a sense of personal achievement. A person afraid of COVID-19 could have a lower sense of personal achievement. People who fear the disease may feel a great deal of tension and be much more preoccupied with a pandemic situation than with their work and success. In addition, many of the situations in which teachers could take pride in performing their work and the sense of achievement during a pandemic have been severely reduced. Due to COVID-19-related restrictions and remote work, teachers likely had fewer sources from which they could derive satisfaction. For example, many student competitions were not held, so it was more difficult to observe the educational successes of the teachers’ students. All these circumstances, along with the fear of COVID-19, could have contributed to a reduction in the sense of personal achievement.

The current study shows that fear of COVID-19 is associated with two dimensions of burnout – emotional exhaustion and a sense of personal achievement. All elements of occupational burnout were related to studied Polish teachers’ job satisfaction. Two dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion and a sense of personal achievement) mediated between fear of COVID-19 and teacher satisfaction. The feeling of danger during a pandemic related to the feeling of fear, contributing to increased tension and exhaustion, could make teachers develop the syndrome of professional burnout, which in turn can reduce their job satisfaction. This means that emotional exhaustion and a sense of personal achievement mediated the effect of fear of COVID-19 on job satisfaction. On the other hand, depersonalization, although acting as a predictor of job satisfaction, did not act as a mediator between fear of COVID-19 and job satisfaction. Fear of COVID-19 manifests itself primarily at the level of the individual, which in turn makes the interpersonal element of burnout (depersonalization) less perceptible. It is worth emphasizing that teachers working remotely could have contact with their students all the time, which is reflected in the lack of relationship between the fear of infection and depersonalization. At the same time, this contact is qualitatively different and to a large extent worse than direct contact, which is reflected in the observed relationship between depersonalization and job satisfaction. Unfortunately, this study does not provide any data to confirm this relationship.

Our study showed that emotional exhaustion and a sense of personal achievement were the strongest predictors of job satisfaction. A burned-out person, feeling emotionally exhausted and tenser, will perceive their job as less satisfactory (Kim et al., 2017). Worse relationships with students and a lack of personal contacts can also cause depersonalization, which leads to lower job satisfaction (see Park & Shin, 2020). Our study revealed a positive relationship between the sense of personal achievements and job satisfaction. It could indicate that people who achieve success at work are more satisfied with it. It has been confirmed in previous studies (Kara, 2020; Kim et al., 2017).

LIMITATIONS

The major limitation of the present study is its cross-sectional nature. Although previous research supported the adoption of the present hypothesis, the epidemiological situation significantly limited the potential for pre-post data collection, which would be best suited to verify the hypothesized relations. Additional limitations include the gender disproportion in the respondents, which is quite typical for the teaching profession in Poland. On top of that, there was a limited possibility to compare different forms of a teacher’s work environment, as most of the respondents worked remotely. In future studies, it would be beneficial to analyse the level of burnout and job satisfaction in teachers after the pandemic ends.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study showed a relationship between the risk perception of COVID-19, occupational burnout and job satisfaction in Polish teachers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Polish teachers were a group that was very affected in terms of the performance of professional duties during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were at risk of falling ill during in-person work and had to adapt quickly to changing forms of work during successive waves of the pandemic. Many of them could feel a high risk of contracting and fear of COVID-19, similar to that of healthcare workers, which contributed to their occupational burnout and therefore job satisfaction. We found that two dimensions of burnout (emotional exhaustion and a sense of personal achievement) mediated between fear of COVID-19 and teachers’ job satisfaction. Investigating the relationships that occur between the described variables is of particular interest during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results obtained in the study may contribute to the understanding of the effects of the pandemic for the professional group of educators. The obtained results may be an indication for further analyses of occupational burnout and job satisfaction and may serve as an inspiration to discover the factors that protect against the development of burnout syndrome and a decline in employee satisfaction. Research in the field of occupational psychology can be particularly useful at a time when we are dealing with changes in the form of work, which have been largely driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary materials are available on the journal’s website.