BACKGROUND

PERSONALITY AND RESILIENCE

In general, personality psychology deals with identifying specific characteristics of human nature, namely, (1) what makes humans alike, and (2) how humans differ regarding those characteristics (e.g., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness; Hogan & Blickle, 2013). In this regard, researchers showed that resilience is an important individual difference that is responsible for facilitating the adaptation of individuals to their environment (Windle, 2011). Resilience reflects individual difference in how an individual mobilizes his personal and external resources to overcome stressors and trauma (Windle, 2011). As a consequence, researchers tried to identify the factors that contribute to resilience, intending to develop valid psychological interventions that target resilience.

Many authors have concluded that personality traits represent an important category of predictors of resilience (Oken et al., 2015). Individuals high on extraversion, agreeableness, or emotional stability reported high levels of resilience (Oshio et al., 2018). Also, researchers found a positive relationship between openness to experience and conscientiousness on the one hand and resilience on the other hand (Wolf et al., 2012).

We chose the Big Five personality factors as potential predictors of resilience as personality traits reflect broad and stable behavioral predispositions that manifest cross-situationally (Saucier et al., 2014) and predict a variety of adaptive and maladaptive behavior. In this regard, considering that individuals high on the Big Five factors are also high on ego development, and are perceived as mature and fully functional individuals (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008), we consider that they should have adaptive coping styles that are reflected in high resilience. Moreover, considering the nature of self-determination and autonomous orientation (e.g., self-determination being an indicator of ego development), we consider that the Big Five factors should have an indirect effect on resilience through self-determination.

Others perceive people characterized by high extraversion as energetic, dynamic, joyful, cheerful, sociable, and talkative (Burtaverde & De Raad, 2019). Therefore, it can be seen that positive emotions are a core characteristic of extraversion. As such, individuals high in extraversion tend to have adaptive coping skills that help when confronted with negative events. This may be the principal reason why extraversion is positively associated with resilience (Oshio et al., 2018).

Agreeableness is characterized by prosocial behavior and empathy (Lee & Ashton, 2004). It was found that agreeableness is positively related to resilience (Waaktaar & Torgersen, 2010). A possible explanation may be that because agreeable individuals have moral and prosocial values, these values make them motivated to establish and pursue prosocial and humanitarian goals, and they have the necessary personal resources to fulfill them as agreeable individuals are high on ego development (Kurtz & Tiegreen, 2005), making them more resilient.

Conscientious individuals are perceived by others as organized, perfectionist, diligent, and efficient (Saucier et al., 2014). Conscientiousness is positively related to career success and satisfaction (Burtaverde & Iliescu, 2019). Researchers found that conscientiousness is positively related to resilience (Nakaya et al., 2006). A possible explanation may be that individuals high in conscientiousness have satisfied the need for competence, one of the three human basic needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness; Sheldon & Prentice, 2019). Individuals who have the three basic needs fulfilled have problem-focused coping styles (Berzonsky, 2004). This is also the case of people with high conscientiousness (Roesch et al., 2006), which should make them more resilient.

Others describe emotionally stable individuals as even-tempered, calm, patient, and moderate (Saucier et al., 2014). Emotional stability was positively related to life satisfaction and relationship satisfaction (Burtaverde et al., 2018), efficient coping styles (Roesch et al., 2006), and good mental health (Lamers et al., 2012). It was found that emotional stability was positively related to resilience (Nakaya et al., 2006). A possible explanation may be that emotionally stable individuals may have fulfilled the three basic needs, especially the need for autonomy and relatedness, which help them overcome aversive and negative life events. This idea is sustained by the fact that individuals with low levels of emotional stability such as those characterized by borderline personality disorder manifest maladaptive romantic relationships style (fluctuations between idealizations vs. depreciation of the same individual; Drapeau et al., 2012), fear of abandonment (Schmahl et al., 2003), or have suicidal thoughts (Oldham, 2006), which may be an indicator of low resilience.

Others characterize individuals high on openness to experience as creative, curious, innovative, and rebellious (Burtaverde & De Raad, 2019). Openness to experience was related to rebelliousness (Burtaverde & De Raad, 2019). Researchers showed that openness was positively related to resilience (Oshio et al., 2018). A possible explanation of this relationship may be that people high in openness to experience are also ego-resilient and high on ego development (Kurtz & Tiegreen, 2005; Sava & Popa, 2011), and are perceived by others as more independent. Therefore, these individuals establish clear personal goals that should help them develop and invest high levels of energy in pursuing them, making them more resilient in the face of obstacles and negative events.

SELF-DETERMINATION AS AN EXPLICATIVE MECHANISM OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERSONALITY AND RESILIENCE

However, research in the area of personality and resilience is sparse. Researchers have used various personality models as predictors of resilience that were usually chosen subjectively, without a solid theoretical argumentation for choosing one or another personality model. As we already mentioned, various studies have focused on the role of the Big Five personality model (Oken et al., 2015), temperament-based subtypes (Wolf et al., 2012), and disorder-related traits (Amstadter et al., 2016). The direct gap left open by this state of affairs is that we do not have explanatory mechanisms for this relationship.

We propose self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) as a theoretical framework that should explain the relationship between personality and resilience and should contribute to conceptualizing an explanatory mechanism of the relationship. Self-determination theory aims to explain human behavior, which means that it considers people’s experience as the proximal determinant of action (Ryan & Deci, 2008). The theory focuses on how people interpret internal or external stimuli, which gain meaning from their direct or indirect relation to people’s basic psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In this regard, self-determination theory (SDT) differentiates types of motivation along a continuum from controlled to autonomous (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Although there are six mini-theories aimed at explaining the meta-theory of self-determination, in this paper, we will rely on the causality orientations theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). We chose this theory as this is a theoretical model that explains the theory in terms of personality related individual differences (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The authors proposed three types of general causality orientations: the autonomy orientation, the controlled orientation, and the impersonal orientation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). These constructs aim to explain orientations toward the environment and toward one’s own motivations (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Moreover, causality orientations theory may be understood as a theoretical framework that refers to individual differences in ego development (Sheldon & Prentice, 2019), which may be useful to explain the link between personality traits and resilience. For example, impersonal and controlled orientations decreased during the four-year college study period, and autonomous orientations increased for those students who engaged in extracurricular activities (Sheldon & Salisbury, 2017), which may be an indicator of ego development stimulated by the values, behaviors, and attitudes promoted by universities.

The autonomy orientation refers to people who adapt to their environment by perceiving it as a source of relevant information, as they are interested in both external events and their inner experiences. People characterized by autonomy orientation have a great extent of experienced choice with respect to the initiation and regulation of their own behavior. They look for opportunities for self-determination and choice and have an internal locus of causality (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The controlled orientation refers to the degree to which the attention of the individuals is oriented on external contingencies (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In the determination of cognitions, emotions, and behavior, an important role is played by the pressure of initiating and regulatory events. In this regard, they behave in a certain manner because they think they “should,” and they rely on controlling events (e.g., deadlines). In the case of those characterized by controlled orientation, extrinsic rewards (e.g., status, remuneration) are more important in determining their behavior (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The impersonal orientation characterizes those individuals who experience their behavior as being beyond their control (Ryan & Deci, 2017). People high in impersonal orientation perceive themselves as unable to master situations and incompetent. Also, they perceive that the outcomes of the tasks they perform are not related to their behavior.

Self-determination theory assumes that autonomy is not just a psychological need that can be fulfilled more or less by a situation but also a feature of people’s personalities. As such, this theoretical model is conceptually congruent with many influential past theories from the field of personality such as those proposed by Loevinger (1985), Kohlberg (1973), or Erikson and Eriskon (1981). These theoretical models assume that autonomy is an outcome that reflects developmental achievement. When people reach psychological maturity, they learn to differentiate themselves from the social context, be aware of their interests or values as potentially different from the requirements imposed by the environment and contexts, and appropriately express and negotiate resolutions to any conflicts that may arise. Sheldon and Prentice (2019) argued that the three causality orientation types (autonomy orientation, control orientation, and impersonal orientation) should be understood as ego development markers. Researchers showed that autonomous orientation is positively linked with ego development, self-esteem, and self-actualization (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Controlled and impersonal orientations should be understood as low ego development indicators (Sheldon & Prentice, 2019). Further, the ego development of an individual should be reflected in the personality structure, which is best represented by the Big Five meta factors (Saucier et al., 2014). Individuals high on the Big Five traits – extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience – are considered to be high on ego development. Thus, developing toward high levels of emotional stability and higher levels of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and, to a certain degree, extraversion is described as reflecting an arc of socio-emotional maturation in personality development (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008).

As ego development is related to resilience (Leipold & Greve, 2009), we consider that causality orientations would play an important role in the associations between the Big Five personality traits and resilience. Social problems and challenges are successfully resolved if the individual possessed the necessary adaptive coping styles (Leipold & Greve, 2009) that are reflected in high resiliency. Resilience is considered a resource that allows a favorable performance under stress (Weed et al., 2006). Confrontation with an adverse situation will lead to successful outcomes only when the individual possesses the social skills, sufficient emotion regulation competence, and the cognitive flexibility that are necessary to revise initial perceptions of the environment (Brandtstädter, 2006). These features are specific to individuals high on ego development (Leipold & Greve, 2009). Considering that self-determination is an indicator of ego development, we consider that self-determination theory should be useful in explaining the link between the Big Five factors and resiliency, where self-determination should act as a mediator in this relationship.

THE CURRENT STUDY

To sum up, this study aims to test the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and resilience, relying on self-determination theory as an explanatory mechanism. In this regard, we will test the mediation role of self-determination in the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and resilience.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

We used G*Power to determine the necessary sample size to obtain significant effect sizes. The minimum required sample size for an effect size (r) of .25, with α set at .95, and statistical power set at .90, was 130 participants, for the regression analysis. We relied on a community sample that consisted of 252 (Mage = 26.38, SD = 10.17, 62.5% women, 39.5% men) participants voluntarily recruited from various social media platforms, with an age range between 17 and 67 years. All the participants were recruited from Romania, all of them being Romanians. Participants were briefly informed about the aim of the research, and all of them consented to participate. The measures were administered online via Google Forms. The average completion time was 20 minutes.

MEASURES

The Big Five traits were assessed using the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John et al., 2008). The measure consists of 44 items that assess: extraversion (8 items, α = .84; e.g. “I am a talkative person”), agreeableness (9 items, α = .71; e.g. “I am a forgiving person”), conscientiousness (9 items, α = .84; e.g. “I am an organized person”), neuroticism (8 items, α = .88; e.g. “I am worrying person”), and openness to experience (10 items, α = .81; e.g. “I am a person who is curious about many different things”). All the items were scored on a Likert scale with five response options from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Resilience was measured with the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Connor & Davidson, 2003). It consists of 25 items (α = .91) rated on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), e.g. “Able to adapt to change”, “Not easily discouraged by failure”. All the items are summed to form a composite resilience score.

Self-determination was assessed with the General Causality Orientation Scale (GCOS; Deci & Ryan, 1985). The scale consists of 12 vignettes that assess the three main causality orientations: autonomous (α = .78), controlled (α = .73), and impersonal (α = .79). Each vignette has three a priori established scenarios (affirmations), one for each causality orientation. Each scenario is rated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (to a great extent). Therefore, there are 36 items, 12 for each causality orientation.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the correlations between the variables of the research as well as the descriptive statistics. We can see that extraversion was positively related to resilience and controlled orientation and negatively related to impersonal orientation. Agreeableness was positively related to resilience and negatively related to impersonal orientation. Conscientiousness was positively related to resilience and negatively related to impersonal orientation. Neuroticism was negatively related to resilience and positively related to controlled orientation and impersonal orientation. Openness to experience was positively related to resilience and autonomous orientation and negatively related to impersonal orientation.

Table 1

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for all the variables of the study

To test the predictive power of personality traits and causality orientation for resilience, a hierarchical linear regression was used (Table 2). In Step 1, we introduced age and gender to control for the effect of potential confounding demographic variables. In Step 2, we included the Big Five personality traits, and in Step 3, we included the three causality orientations. Controlling for age and gender, we can observe that the Big Five personality traits predicted 57% of the variance of resilience (R2 = .57), the model being statistically significant with F(7, 144) = 27.10, p < .001. Extraversion and conscientiousness were positive predictors of resilience, whereas neuroticism was a negative predictor. Controlling for age, gender, and the Big Five personality factors, controlled orientations added a statistically significant 3% increment in the prediction of resilience (D R2 = .03), the model being significant with F(10, 141) = 21.30, p < .001. Controlled orientation was a significant positive predictor of resilience, while impersonal orientation was a significant negative predictor of it.

Table 2

Hierarchical linear regression on the predictive power of personality traits and causality orientation on resilience

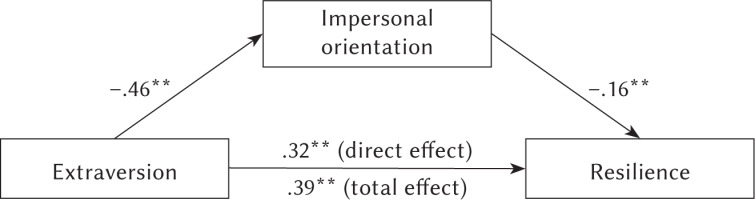

To test if self-determination mediates the relationship between the Big Five personality factors, we used the medmod package for R and Jamovi to perform mediation analysis (see Figures 1-5). We can see that extraversion was negatively related to impersonal orientation (low self-determination) (β = –.46, p < .001). Impersonal orientation was negatively related to resilience (β = –.16, p < .001). Extraversion was positively related to resilience (β = .39, p < .001). Controlling for impersonal orientation, extraversion showed a weaker effect on resilience (β = .32, p = .003), the indirect effect being significant (β = .07, p = .003), which suggests partial mediation.

Figure 1

Mediation analysis for the relationship between extraversion, impersonal orientation, and resilience

Note. **p < .01.

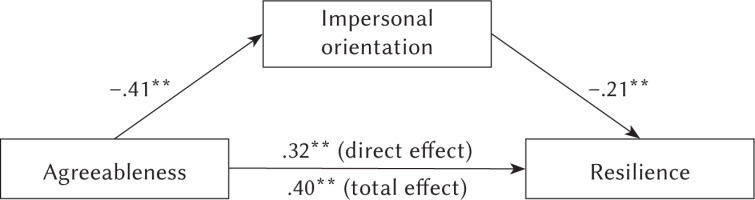

Figure 2

Mediation analysis for the relationship between agreeableness, impersonal orientation, and resilience

Note. **p < .01.

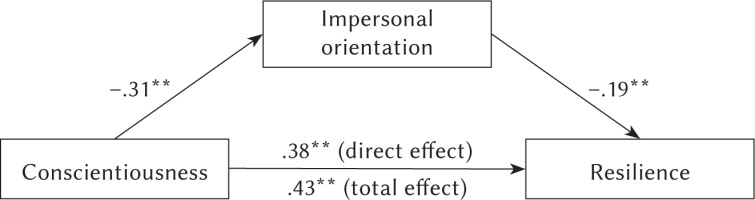

Figure 3

Mediation analysis for the relationship between conscientiousness, impersonal orientation, and resilience

Note. **p < .01.

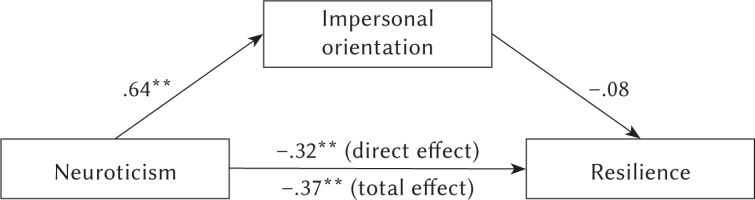

Figure 4

Mediation analysis for the relationship between neuroticism, impersonal orientation, and resilience

Note. **p < .01.

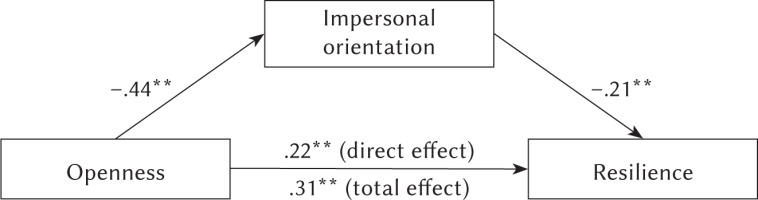

Figure 5

Mediation analysis for the relationship between openness to experience, impersonal orientation, and resilience

Note. **p < .01.

Regarding agreeableness, it negatively predicted impersonal orientation (β = –.40, p = .002). Impersonal orientation negatively predicted resilience (β = –.21, p < .001). Agreeableness positively predicted resilience (β = .40, p < .001). Controlling for impersonal orientation, agreeableness showed a weakened direct effect on resilience (β = .32, p = .008), the indirect effect being significant (β = .08, p = .008), which suggests partial mediation.

As for conscientiousness, it negatively predicted impersonal orientation (β = –.30, p = .004). Impersonal orientation negatively predicted resilience (β = –.19, p < .001). Conscientiousness positively predicted resilience (β = .44, p < .001). After controlling for impersonal orientation, conscientiousness showed a weaker effect on resilience (β = .38, p = .013), the indirect effect being significant (β = .06, p = .013), suggesting partial mediation.

In the case of openness to experience, it was negatively related to impersonal orientation (β = –.44, p < .001). Impersonal orientation was negatively related to resilience (β = –.21, p < .001). Openness to experience was positively related to resilience (β = .31, p < .001). When controlling for impersonal orientation, openness had a weaker effect on resilience (β = .22, p < .001), the indirect effect being significant (β = .09, p = .003), which suggests partial mediation. Impersonal orientation did not mediate the relationship between neuroticism and resilience.

DISCUSSION

The main aim of this research was to investigate the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and resilience, testing the potential mediating effect of self-determination, more specifically, the three types of general causality orientations. We replicated the findings of other research, where the Big Five personality were predictors of resilience (Oshio et al., 2018). In line with other research findings, resilience showed a negative association with neuroticism and positive associations with extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Also, we found that, from the three types of general causality orientations, impersonal orientation partially mediated the relationship between resilience and the Big Five factors, excepting neuroticism.

These findings can be discussed as follows: people high on extraversion were high on resilience. This may be because individuals with high levels of extraversion are high on positive emotions (Burtaverde et al., 2018), which may be a reflection of high ego development, as individuals high on ego development scored high on positive emotions and well-being (Bauer et al., 2011). The high functioning ego may help extraverts to find the energy and adaptive coping skills to solve negative life events they encounter. We also found an indirect relationship between extraversion and resilience through impersonal causality orientation (low self-determination). More specifically, the confidence and social support that characterize individuals high on extraversion could be revealed through low impersonal orientation, which indicates that these people perceive themselves as competent and dare to deal with challenges and obstacles (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Therefore, extraverted individuals should have a better chance of remaining resilient through low impersonal orientation.

Agreeableness was associated with high levels of resilience owing to characteristics such as empathetic, moral, warm, and forgiving (Lee & Ashton, 2004; Saucier et al., 2014) and impersonal orientation mediated the relationship. This finding may be explained by the fact that because agreeable individuals are characterized by moral and prosocial values, these values make them motivated to establish prosocial and humanitarian goals, as they have the necessary personal resources to fulfill them because agreeable individuals are high on ego development (Kurtz & Tiegreen, 2005), making them higher on resilience. Regarding the mediating role of impersonal orientation in the relationship between agreeableness and resilience, we believe that it can be explained by the association between ego development and self-determination (Sheldon & Prentice, 2019). As low impersonal orientation reflects high ego development, individuals with high levels of agreeableness are also high on resilience through low impersonal orientation, because agreeable individuals are also high on ego development.

Individuals high on conscientiousness were high on resilience. This association may be explained by conscientious individuals’ ability to use problem-focused coping styles and high levels of self-control, diligence, and motivation toward accomplishments (Roesch et al., 2006; Saucier et al., 2014). Because, in general, they are successful in what they do (Hill et al., 2014; Burtaverde & Iliescu, 2019), they are resilient through a low level of impersonal orientation. A possible explanation may be that individuals high in conscientiousness have satisfied the need for competence, one of the three human basic needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness; Sheldon & Prentice, 2019). As a consequence, they should be aware of their abilities and feel very effective and capable, even in hard tasks or long-term problems, making them high on resilience.

The last factor associated with resilience was openness to experience. Considering that those high on openness are creative and innovative (Burtaverde & De Raad, 2019), we expect them to stay engaged to find unconventional and unique answers in demanding circumstances that require high resilience. Having extensive knowledge and an analytical tendency helps them in emotional regulation and processing emotional information from a stressful context (Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2014). There was an indirect association between openness to experience and resilience through low impersonal orientation. A possible explanation of this indirect relationship may be that people high on openness to experience are also ego-resilient and high on ego development (Kurtz & Tiegreen, 2005; Sava & Popa, 2011), and are perceived by others as more independent. As ego development is a feature of self-determined individuals (such as those low on impersonal orientation), individuals high on openness to experience establish clear personal goals that should help them develop and invest high levels of energy in pursuing them, making them more resilient in the face of obstacles and negative events.

The findings of this research have practical implications for psychotherapists in their interventions. It is acknowledged that resilience is necessary to choose adaptive coping strategies to overcome stressors and trauma (Windle, 2011). On the one hand, we need to know the individual differences that could stimulate resilience under challenging situations. Consequently, psychotherapeutic programs can be tailored by taking into account the individuals’ personality characteristics, which may reflect important resources of the individuals for the therapeutic process. Being high on traits such as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or openness to experience may offer important information to the psychotherapists regarding the individuals’ ego functioning and resilience.

On the other hand, it could be important for psychotherapists to identify the causes that make some individuals less resilient, as it may help them adapt the therapeutic process to the client’s characteristics. Training clients’ resilience can be more accessible based on their features (i.e., knowing their causality orientation and the extent to which they are self-determined).

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

While this is one of the first studies to propose an explicative mechanism of the link between personality and resilience, there are several limitations as well. Firstly, the sample size was small. This could be an obstacle because a small sample size is associated with low statistical power and increases the margin of error (Coolican, 2017). Further studies may consider collecting larger and more representative samples to replicate and extend the findings of this research. Secondly, our study was cross-sectional, which does not permit us to make causal inferences regarding the relationship between personality and resilience. Thirdly, researchers argued that mediation findings on cross-sectional data might lack ecological validity (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Therefore, further research should test the relationship between personality, self-determination, and resilience, relying on longitudinal designs. Fourthly, some of the resilience characteristics are linked with emotional intelligence in stress responses (i.e., more positive and less negative affect, adaptive strategies to deal with discomfort and adversity; Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2014). Therefore, further studies may take into account emotional intelligence in their design and examine the relationship with general causality orientations, primarily impersonal orientation.

In conclusion, this study showed that individuals high on resilience are also high on extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. It also revealed the impersonal orientation’s partial mediating effect on these relationships. Relying on the low impersonal orientation components (e.g., sense of competence, determination, lack of anxiety, or depression; Ryan & Deci, 2017), scientists and practitioners can enhance resilience by teaching their clients to be more self-determined.