BACKGROUND

Citizenship activity (civic behaviours) is understood in various ways in the literature. Traditionally, citizenship activity reflects the relationship between a person (citizen) and the state/nation (Kennedy, 2006). It expresses a rather low level of civic engagement and mainly refers to the notions of civic virtues, duty or obligations (Wong et al., 2017; Zalewska & Krzywosz- Rynkiewicz, 2018). In a narrow modern approach, citizenship activity reflects the relationships between an individual and everyday life. It is called “active citizenship” and means the individual’s involvement in personal and social affairs, expressed in conventional political participation (e.g. party membership), non-conventional political participation (e.g. protesting), and civic participation (e.g. helping others) (Klamut, 2015; Lewicka, 2005; Torney-Purta, 2003). Nowadays, it also includes political and civic online participation (e.g. Kennedy et al., 2021; Stefani et al., 2021). It refers to the notions of rights, participation and engagement (Torney-Purta, 2003; Wong et al., 2017; Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2018), and many contemporary studies focus on active citizenship as the most desirable because it expresses the greatest civic commitment.

However, the role and adaptive function of different levels of civic engagement may vary depending on the culture, on socio-economic (Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2017), historical and political context (Kennedy et al., 2018; Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2018). Therefore, a broad model of citizenship activity is needed (Barret & Brunton-Smith, 2014; Ekman & Amnå, 2012; Kennedy, 2006, 2018; Theiss-Morse, 1993; Tzankova et al., 2020; Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011, 2018), in particular covering both traditional and narrow contemporary approaches, as well as knowledge of the factors influencing various civic behaviours.

Zalewska and Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz (2011, 2018) proposed such a broad model of citizenship activity, inspired by Kennedy’s (2006) concept. In it, civic activity is understood as a multidimensional construct, consisting of two approaches (traditional and narrow modern) and three forms of civic engagement expressed in a wide range of behaviour categories: passive (national identity and patriotism), semi-active (loyalty and voting), and active (social, political, change-oriented and personal activity).

This model was the basis for extensive research on the forms of civic engagement and the dimensions of citizenship behaviours among children and adolescents. Their results showed that the dimensions of civic behaviours depend on factors at the macro (cross-cultural – Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2017, 2018), mezzo (demographic and social variables – Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2018; Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011) and micro levels – psychological characteristics (Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2020; Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011; Zalewska & Wiśniewska, 2020) and personal experiences, e.g. well-being (Zalewska & Zawadzka, 2016).

However, these findings come from a group that has limited formal civil rights. It seems important to know the typical profile of citizenship activity and factors determining various civic behaviour of young citizens who already have civil rights and can decide about manifestations of their citizenship. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine such a profile and psychological factors (micro perspective) – personality constructs (self-esteem and social skills) and personal experiences (emotional, social and psychological well-being) – as correlates and predictors of citizenship activity dimensions in young citizens aged 19-25 (emerging adults – Arnett, 2000). Such knowledge may be useful for citizenship promotion policies aimed at increasing the propensity to take up various forms of civic activity, as all these variables can be modified through deliberate influences and interventions.

THE BROAD CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY MODEL

The broad model of citizenship activity proposed by Zalewska and Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz (2011, 2018; Zalewska & Nosek, 2020) encompasses a traditional approach expressed in two forms of citizenship engagement (passive and semi-active) and a narrow modern approach (active citizenship) represented by 4 dimensions of behaviours.

Passive citizenship – behaviours expressing attitudes towards the state/nation

National identity. It denotes a sense of belonging to a nation and an expression of symbolic patriotism (Parker, 2009). National identity manifests itself in behaviours expressing a positive assessment and respect for the national values, history, myths and symbols – a flag, coat of arms or national anthem (Kennedy, 2006, 2018).

Patriotism. It is associated with a sense of national pride, also known as glorification or blind patriotism (Parker, 2009). It manifests itself in more extreme behaviour than national identity – expressing readiness to defend one’s own state in the case of external threats (joining the army to defend independence) and sometimes in supporting beliefs that one’s own nation is better than others, taking the form of nationalism or outright hostility towards other groups (Kennedy, 2018).

Semi-active citizenship – behaviours expressing acceptance of the social order and institutional trust

Voting. Conscious voting in elections requires some more interest and involvement in social matters (seeking information in order to make the right choice) than passive citizenship, but it is less than in the case of political activity. Voting also has different predictors (citizenship knowledge and institutional trust) than other manifestations of political activity (affective social trust and a sense of self-efficacy) (Barrett & Brunton-Smith, 2014).

Loyalty. It manifests itself in daily behaviour expressing respect for state institutions, observance of the law and rules, and honest daily work. Such behaviours, like voting, depend on social knowledge and institutional trust (Wojciszke, 2015) and are also attributes of the civic virtues (Wong et al., 2017; Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2018).

Active citizenship – behaviours expressing the greatest civic engagement

Political activity. It means active involvement in politics and includes legal and constructive forms of political activity: intentions of joining a party or running for election, participation in authorities, representing local government, supporting a party or party leaders. Conventional political activity as understood by Kennedy (2006, 2018), Ekman and Amnå (2012) or Stefani et al. (2021) differs from this category because it includes voting as well.

Change-oriented activity (action for changes). It is also called non-conventional (Barrett & Brunton-Smith, 2014) or extra-parliamentary political activity (Ekman & Amnå, 2012; Stefani et al., 2021). It manifests itself in protesting, striving to control authorities and changing the existing order, both legal (protesting, signing petitions, participating in demonstrations) and illegal, such as blocking traffic, occupying buildings, or painting graffiti.

Social activity. It includes participation in charity campaigns, voluntary activities for the environment or groups of people called a social movement (Kennedy, 2006) or voluntary activities (Kennedy, 2018). Additionally, it manifests itself in participation in the life of the local community, building and maintaining its identity (Barrett & Brunton-Smith, 2014; Ekman & Amnå, 2012; Klamut, 2015; Lewicka, 2005; Stefani et al. 2021).

Personal activity oriented to self-development. It includes behaviours aimed at increasing one’s knowledge, skills and abilities, and controlling one’s own development and learning, striving for financial independence, developing creativity, and entrepreneurial ideas. These behaviours can increase contributions to the community and are associated with self-regulation and individualistic values (Kennedy, 2018).

A PROFILE OF CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY IN EMERGING ADULTS

According to Arnett (2000), socio-cultural changes in highly developed countries have shaped a new phase of development, which occurs between adolescence and early adulthood and is associated with a long period of education and gaining a social position. People aged 18-25 (even up to 29) are not financially independent, and they have no children or a permanent job. They have a sense of instability and being “in between”. Like adolescents, they do not show much interest in socio-political issues and focus mainly on themselves, looking for their own identity and life goals, with the conviction that they still have many possibilities (everything is still possible). They delay adulthood, the development of mature attitudes and involvement in professional, family and civic obligations (Arnett, 2016).

PERSONALITY CONSTRUCTS AND CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY

The five-factor theory of personality (FFT; McCrae & Costa, 2008) includes two levels of personality constructs: biologically conditioned dispositions (basic personality traits, intelligence and abilities) at level 1 and characteristic adaptations at level 2. Characteristic adaptations are socio-cognitive personality constructs (e.g. values, attitudes, competences and skills, beliefs about oneself and the world). “They are characteristic because they reflect the enduring psychological core of the individual, and they are adaptations because they help the individual fit into the ever-changing social environment” (McCrae & Costa, 2008, pp. 163–164). They express individual differences that are shaped in the course of the lifespan by basic traits, external factors (sociocultural, situational) and personal experiences connected to biographical elements (activities, behaviours, emotions). They can be modified by intentional social actions and interventions and are more closely related to behaviour than traits, since the FFT suggests that characteristic adaptations together with external factors may directly predict biographical elements (e.g. behaviours, emotions, subjective states). In the present study characteristic adaptations are represented by self-esteem and social skills.

SELF-ESTEEM AND CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY

Self-esteem is a general positive or negative attitude towards the Self (Rosenberg, 1965). It expresses self-respect, confidence in one’s own values and skills, and is positively related to how people perceive their achievements, abilities, intelligence, and popularity. It is positively associated with life satisfaction and other beliefs about oneself (optimism and hope for success – e.g. Łaguna et al., 2007, a sense of self-efficacy, internal locus of control – e.g. Bono & Judge, 2003), and four personality traits, excluding neuroticism, with which it is negatively associated (e.g. Anglim et al., 2020; Bono & Judge, 2003). These four traits (conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and openness to experience) are positively associated with various dimensions of citizenship activity (KrzywoszRynkiewicz et al., 2020). Self-esteem determines motivation, choice of goals, persistence in implementation and, above all, undertaking various activities (Łaguna et al., 2007; Rosenberg, 1965), so it probably facilitates active citizenship.

SOCIAL SKILLS AND CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY

Social skills means proficiency in understanding social rules and planning action strategies in order to effectively influence other people in social situations and achieve the intended goals (Argyle, 1994). According to Matczak (2007), social skills are competences acquired in the course of the lifespan through social interactions (at home, at school, at work) that help to cope with specific situations. They also depend on biologically conditioned dispositions (intelligence, personality and temperament traits). Based on the classification of difficult situations presented by Argyle (1994), Matczak (2007) distinguished the basic social skills that determine the effectiveness of behaviour in three types of real social situations:

Social skills in intimate situations (SS-I). They are needed in close contacts with relatives and professionals, associated with disclosure to the partners of the interaction (e.g. confiding in them or providing support). They are based on personal trust and include non-verbal communication skills, the application of the principles of good communication (active listening, and revealing oneself), and the ability to reward (Argyle, 1994; Matczak, 2007).

Social skills in situations of social exposure (SS-E). They are required in situations where a person is a potential object of attention or evaluation of other people (Matczak, 2007). These situations are very stimulating, demanding and stressful; they can be interpreted as difficult and threatening. Skills in social exposure situations mean that in judgmental situations, the person achieves goals without excessive psychological and psychophysiological costs (Argyle, 1994; Matczak, 2007). They are related to the desire to protect or increase self-esteem, and to build and maintain a specific identity.

Social skills in situations requiring assertiveness (SS-A). They are needed in situations when there is a conflict of interests, beliefs or needs, values, and rights (Argyle, 1994; Matczak 2007). Assertive skills means taking actions consistent with one’s own interests (achieving one’s goals or fulfilling needs, including defending one’s rights, expressing beliefs, feelings and thoughts) without unnecessary fear, and at the same time without violating the rights of others (Matczak, 2007).

Considering the definitions of civic dimensions and specific social skills, it can be assumed that skills in exposure situations will play a key positive role in all types of civic activity, and the two other social skills will be related mostly to personal activity.

WELL-BEING AND CITIZENSHIP ACTIVITY

Well-being is a polysemic phenomenon and may be considered from several perspectives. From the perspective of understanding the essence of happiness, the hedonic (seeking pleasure from any source and avoiding pain and displeasure) and eudaimonic (striving for self-discovery and self-realization, optimal functioning) aspects of well-being are distinguished (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Both of these aspects can be assessed on the basis of objective indicators (e.g. assessment of someone’s happiness or satisfaction by others, clinical diagnosis of mental health) or self-report measures. Moreover, self-report measures may reflect a subjective, objective or a mixed approach to well-being depending on the assessment criteria (Veenhoven, 1988). In the subjective approach, the well-being assessment is based on one’s own criteria (hedonic or eudaimonic), mostly not disclosed in the study (e.g. Pavot & Diener, 1993). In an objective or normative approach, criteria associated with living conditions (e.g. income), social life or personal characteristics (e.g. virtues, values) are strictly defined by theories or researchers (e.g. Keyes, 1998; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). In the mixed approach, subjective and objective criteria are taken into account (e.g. Karaś et al., 2014; Keyes, 2002; Veenhoven, 1988).

Some contemporary theories try to integrate different aspects and approaches into well-being (e.g. Seligman, 2002). One of them is proposed by Keyes (2002; Keyes & Waterman, 2003), who presented a three-dimensional (emotional, psychological, and social) concept of well-being. Emotional well-being represents a subjective approach and hedonic aspect, and means positive feelings, happiness and positive attitude towards one’s life. The objective approach and eudaimonic aspect (striving for self-actualization and optimal functioning) is represented by two dimensions: psychological and social well-being. Psychological well-being means functioning well as a person and consists of six components from Ryff’s model (e.g. Ryff & Keyes, 1995): self-acceptance, personal growth, autonomy, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and environmental mastery. Social well-being means functioning well in a social context and includes five components (Keyes, 1998): social integration, social acceptance, social actualization, social contribution, and social coherence.

Among adults, the three well-being dimensions are related to personality traits, self-esteem, personal control, optimism, volunteering and other socially desirable behaviours (Keyes & Waterman, 2003). In longitudinal studies, well-being depends on activity in society, but also well-being dimensions, especially social well-being, foster and support productivity and the desired social behaviours, including volunteering (Keyes & Waterman, 2003; Son & Wilson, 2012). There is also evidence that well-being in the subjective approach (happiness or life satisfaction) makes people more active and involved in the environment, more venturesome and sensitive to other people (Veenhoven, 1988), and more prone to take up personal and prosocial activity (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005), especially volunteering (Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Among teenagers it allows one to predict three dimensions of citizenship: passive, personal, and social activity (Zalewska & Zawadzka, 2016). Among emerging adults all citizenship dimensions are related to life satisfaction (Zalewska & Nosek, 2020). Thus we can expect that well-being (emotional, psychological, and social) will be positively related to citizenship.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

The aim of the study was to answer the following questions:

Q1. What is the profile of citizenship activity in emerging adults?

Q2. What are relationships between civic activity dimensions and psychological factors: 1) self-esteem and 2) social skills as personality constructs, and 3) three dimensions of well-being as personal experiences?

Q3. What psychological factors are significant predictors of specific civic activity dimensions and what is the contribution of personality constructs, and the additional input of three well-being aspects in predicting citizenship dimensions among emerging adults?

Based on the theoretical and empirical premises presented above, the following hypotheses were formulated – one for question Q1 and three for question Q2 (question Q3 remained open):

H1: Emerging adults will manifest the highest level of personal activity, a lower level of passive and semi-active citizenship, and the lowest level of the other dimensions of active citizenship (social, change-oriented, and political activities).

H2.1: Self-esteem will be positively related to the dimensions of active citizenship.

H2.2: Social skills will be positively related to the dimensions of citizenship activity: skills in exposure situations (SS-E) with all dimensions, but assertive skills (SS-A) and skills in intimate situations (SS-I) only with personal activity.

H2.3: Well-being (emotional, psychological, and social) will be positively related to citizenship.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were 140 emerging adults (50% men) from Poland, aged 19 to 25 (M = 22.39, SD = 1.70): 47 employees in manufacturing companies, 27 working students, and 66 non-working students (from faculties other than psychology, e.g. pedagogy, law). The vast majority (90%) were at least 21 years old and had all civil rights, including standing for election. Most of them (51.4%) came from small towns (up to 20,000), where 53% of the Polish population lives.

PROCEDURE

The research was carried out in groups, at universities (with the consent of lecturers) and production plants (with the consent of the superiors) in November 2018 to February 2019.

The study was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research at SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities. Before the study we received informed consent from all participants.

MEASURES

The Multidimensional Self-esteem Inventory (MSEI) by O’Brien and Epstein (1988) in the Polish adaptation (Fecenec, 2008) was used to assess general self-esteem. This subscale includes 10 items (e.g. “How often do you feel really pleased with yourself?”) with a 5-point answer format from 1 (almost never) to 5 (very often). The reliability index of the measurement in the study group was high – Cronbach’s α = .80.

The Social Skills Inventory (SSI; Matczak, 2007) was used to measure social skills in three types of situation: intimate (SS-I; e.g. “Ask your neighbour for help in the event of a breakdown in the apartment”), social exposure (SS-E; e.g. “Take the floor at the workers’ meeting”), and demanding assertiveness (SS-A; e.g. “Make colleagues aware that their loud conversations are disturbing your work”). This inventory includes 60 diagnostic items (out of 90) with the question “How well do you do the indicated activities?” and 4-point answers: definitely good, not bad, rather poor, definitely bad. The Cronbach’s α indices in the examined group were satisfactory: .74 for SS-I, .80 for SS-E and SS-A.

The Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF; Karaś et al., 2014) consists of 14 items. Each item contains the question: “How often during the past month did you feel…” with a 6-point answer format (0 – never, 1 – once or twice, 2 – about once a week, 3 – 2 or 3 times a week, 4 – almost every day, 5 – every day). The Cronbach’s α indices in the examined group were high: .86 for social (e.g. “that people are basically good”), and .92 for emotional (e.g. “happy”) and psychological (e.g. “that you liked most parts of your personality”) well-being.

The Citizenship Behaviour Questionnaire-30 – general version (CBQ-30; Zalewska & Nosek, 2020). It is a modified version of the Citizenship Behaviour Questionnaire (Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011) that consists of 30 items with 4-point answers (definitely no, probably no, probably yes, definitely yes). It allows one to assess the general citizenship activity (α = .91) and 6 citizenship dimensions: passive (e.g. “Is the Polish flag an important symbol for you?”), semi-active (e.g. “Do you intend to vote in elections?”) and 4 types of activity – political (e.g. “Are you a member of a political party, and if not, do you intend to join a selected party?”), change-oriented (e.g. “Do you participate in any actions or campaigns to defend the interests of certain groups of people?”), social (e.g. “Do you participate in any activities or actions for material help to other people?”), and personal (e.g. “Do you try to solve your problems independently?”). The alpha indices for the dimensions were satisfactory, ranging from .74 to .90.

DATA ANALYSIS

After calculating the descriptive statistics, a series of Student’s t-tests for the dependent sample were performed to determine the profile of civic activity. Next, the relationships between all variables were examined using Pearson’s r correlation. Finally, two steps of hierarchical regression analyses were designed to find significant predictors and determine the contribution of personality constructs, and additional input of three well-being aspects in predicting citizenship dimensions. Before the regression analyses, Harman’s single factor test for all items was executed. Its result (22.6% < 50%) showed that there was no problem with a common method bias.

RESULTS

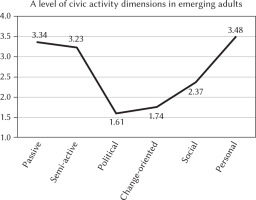

The profile of citizenship activity is shown in Figure 1. The results of the Student’s t-tests for the dependent sample showed that the level of each citizenship dimension differed from the level of the other dimensions (Table 1). Emerging adults manifested the highest level of personal activity, lower but high levels of passive and then semi-active citizenship, a lower and rather moderate level of social activity, even less involvement in change-oriented activity, and the lowest level of political activity. That profile is fully consistent with hypothesis H1. Effect sizes for 11 differences were large (Cohen’s d > 0.8) and for differences between personal activity and the other dimensions of active citizenship were very large (≥ 1.3).

Table 1

Differences between the dimensions of citizenship – results of Student’s t-tests for the dependent sample (N = 140)

Results of correlation analyses (Table 2) partly confirm hypothesis H2.1 – self-esteem was positively related to political, social, and personal activity, but not associated with change-oriented activity. It was additionally related to passive citizenship. They mostly confirm hypothesis H2.2 – skills in intimate situations and assertive skills were positively related only to personal activity (as expected), but skills in social exposure were related not to all, but to four dimensions: political, social, and personal activity, and passive citizenship. Hypothesis H2.3 has full confirmation only for social well-being, which was positively related to all dimensions of citizenship activity. Emotional and psychological well-being were positively related to passive citizenship, social, and personal activity.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlations between examined variables (civic behaviour dimensions, self-esteem, social skills, and well-being) (N=140)

According to Cohen (1992), correlation values of .1 ≤ r < .3 reflect small effects, values of .3 ≤ r < .5 reflect medium effects, and values of r ≥ .5 reflect large effects. Taking these guidelines into account, the results showed positive moderate effects for the relationships of personality constructs with personal activity, for the relationships of well-being aspects with personal and social activity, and for the relationship of social well-being with political activity. All other significant correlations reflected positive small effects.

All civic behaviour dimensions were positively correlated (moderate to large effects) except personal activity (Table 2), which was not associated with semi-active citizenship and the other dimensions of active citizenship. Its relationship with passive citizenship was weak. Also all psychological factors were positively intercorrelated (moderate to large effects); the strongest effects were found for intercor-relations between social skills (.69-.82) and between well-being aspects (.67-.83).

Results of hierarchical regression analyses showed that each dimension of civic activity was differently predicted by a set of analysed psychological factors (see Table 3). Passive citizenship was explained only by personality constructs (about 10% of its variance), and the only significant and positive predictor was skills in social exposure situations. For semi-active citizenship, social and personal activity, personality constructs explained more of their variance (23%, 16%, and 26%) than well-being aspects (4%, 12% and 7%, respectively). For semi-active citizenship and social activity, significant positive predictors were skills in situations of social exposure and social well-being, and the negative predictor was assertive skills. For personal activity significant positive predictors were self-esteem and psychological well-being and the negative predictor was social well-being. For political activity personality constructs explained much less of its variance (9%) than well-being aspects (25%); positive predictors were self-esteem, skills in social exposure situations, and social well-being, and negative predictors were assertive skills and emotional well-being. The set of psychological factors did not significantly explain change-oriented activity, although social well-being was its only significant predictor.

Table 3

Personality constructs (self-esteem and social skills) and well-being as predictors of civic activity dimensions – results of hierarchical regression analyses (N=140)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the typical profile of citizenship activity (differences between dimensions) and psychological factors – personality constructs (self-esteem and social skills) and personal experiences (emotional, social and psychological well-being) – as correlates and predictors of citizenship activity dimensions in emerging adults, young citizens aged 19-25, who already have civic rights and can take up all forms of civic activity. Differences between dimensions were tested with Student’s t-test for the dependent sample and all relationships were tested using Person’s r correlations. Hierarchical regression analyses were used to find significant predictors and to determine the contribution of personality constructs and well-being aspects in predicting each dimension of civic activity.

THE PROFILE OF CIVIC ACTIVITY

The results of Student’s t-tests for the dependent sample fully confirm hypothesis H1. Emerging adults manifested the highest level of personal activity, a lower but still high level of passive, and then semi-active citizenship, and much lower involvement in active citizenship related to socio-politic issues – rather moderate in social activity, lower in change-oriented activity and the lowest in political activity. Although they already have civic rights their profile of civic activity was similar to that of adolescents in Poland (Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011) and other countries (Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz & Zalewska, 2018). Their high level of passive citizenship means that they also displayed a rather strong national identity (contrary to opinions about the crisis of civic identity – Krzywosz- Rynkiewicz & Zorbas, 2020) and patriotism, which partly may result from Polish cultural factors and the growth of national ideas in some European countries, including Poland. Emerging adults, like adolescents, can be described as “politically excluded” (Bently & Oakley, 1999) because they show very little interest in social and political issues. Instead, they focus on their own needs and priorities, protecting individual interests. Important differences between emerging adults and adolescents were found in the citizenship activity intercorrelations. Among adolescents political and change-oriented activities were weakly intercor-related and weakly associated with social activity, and not related to the other intercorrelated dimensions (Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011). Among emerging adults all civic behaviour dimensions were positively correlated except personal activity, which was the most important and independent of the others – only weakly related to passive citizenship. According to Szafraniec (2011), young people do not believe in the effectiveness of the fight for social change, so they look for the best opportunities to achieve their own goals. However, a fairly high level of semi-active citizenship may indicate that emerging adults in Poland during the study period (November 2018 to February 2019) accepted the existing social order and showed quite high loyalty (respect for state institutions, law and rules), and felt no need to get involved in socio-political activity, like adolescents in high-HDI (Human Development Index) countries (Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz et al., 2017). Arnett (2000, 2016) argues that their strong self-concentration and low involvement in professional, family or civic duties reflect their difficulties in achieving independence, maturity and social position in highly developed countries. This interpretation is consistent with the results indicating the significant role of psychological factors in civic activity.

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN EXAMINED PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS AND CIVIC ACTIVITY DIMENSIONS

Correlational analyses partly confirm all the other hypotheses (H2.1-H2.3). Generally, their results are similar to those obtained previously among adolescents. Higher self-esteem (H2.1) and skills in social exposure situations (H2.2) were related to higher active citizenship (political, social and personal activity) and passive citizenship. Among adolescents, these dimensions were associated with hope for success as another socio-cognitive personality construct conducive to undertaking various activities and challenges, as well as persistence in pursuing goals (Zalewska & Wiśniewska, 2020).

As regards well-being (H2.3), higher emotional (happiness and satisfaction) and psychological well-being (striving for self-realisation) were associated with higher passive citizenship, social, and personal activity, and these dimensions were predicted by the general subjective well-being of adolescents (Zalewska & Zawadzka, 2016). Zalewska and Nosek (2020) found that all citizenship dimensions of emerging adults were related to life satisfaction. In this study a higher level of all the dimensions was associated with higher social well-being (optimal social functioning). That result is consistent with findings that social well-being in particular fosters and supports desirable social behaviours (Keyes & Waterman, 2003). However, it may also mean that civic activity facilitates social well-being, as the correlation approach does not allow for conclusions about the direction of dependence, and social activity (Keyes & Waterman, 2003) or volunteering (Son & Wilson, 2012) may have a positive impact on subsequent social well-being.

All significant relations between analysed psychological factors and dimensions of civic activity were positive, weak or moderate, and different for various dimensions. Only personal activity correlated with all examined personality constructs and well-being aspects.

SELF-ESTEEM, SOCIAL SKILLS AND WELL-BEING AS PREDICTORS OF CIVIC ACTIVITY DIMENSIONS

Each civic activity dimension was differently predicted by the set of examined psychological variables. Interestingly, passive and semi-active citizenship, and social and personal activity, which refer to behaviours commonly accepted as manifestations of a “good citizen” (Zalewska & Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, 2011), were explained to a higher degree by personality constructs (characteristic adaptation reflecting the individual core of individuals – McCrae & Costa, 2008) than by well-being aspects. The reverse was the case for the least manifested political activity – its variance was explained by personality constructs much less than by well-being aspects.

The relationships in regression analyses differed from those revealed in correlational analyses. Some relations became insignificant (e.g. between self-esteem and passive citizenship or social activity) – these correlations probably reflected the common effects with other variables. Moreover, simultaneously controlling all variables in regression analyses revealed suppression (Tzelgov & Henik, 1991) – then standardized coefficients for skills in social exposure increased and assertive skills negatively predicted semi-active citizenship, and social and political activity. That means that greater assertive skills can make people more self-centred and egoistic, hindering them from engaging in certain civic behaviours. Similarly, when effects of all variables were controlled, social well-being (experiencing optimal social functioning: integration, contribution, growth, acceptance, and coherence) negatively predicted personal activity, and emotional well-being (experiencing happiness) negatively predicted political activity. Their negative effects were not visible in correlations (see also Oishi et al., 2007; Zalewska & Nosek, 2020), because they are strongly associated with other variables that influence these activities positively.

When the effects of all examined variables were controlled, an important positive role of three variables in predicting dimensions of civic activity among emerging adults was revealed. Higher self-esteem favoured personal and political activity, higher skills in social exposure situations (functioning well in judgmental situations) favoured the manifestation of all forms of citizenship: passive, semi-active and two types of active citizenship – social and political. In turn, higher social well-being conditioning optimal social functioning was conducive to taking up behaviours representing a semi-active form and three types of activity, while inhibiting personal activity. These results indicate that in promoting and increasing civic activity of emerging adults it is necessary to recognise, support and strengthen their self-esteem, skills in exposure situations and social well-being, as all these variables are its significant predictors and can be modified by deliberate influences and interventions.

LIMITATIONS

This study has some limitations. It includes emerging adults living in Poland, and the results may differ in samples with other cultural and socioeconomic characteristics. The data have been gathered by self-reports only. The correlational nature of the study does not allow one to make conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships. The statistical analyses used only considered linear relationships and are not resistant to outliers. Finally, other variables that were not included in this study may affect the explained variables.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Despite its limitations, this study provides new knowledge on the profile of civic activity and the relationships between activity dimensions and psychological factors – first, because they were tested in emerging adults, young citizens aged 19-25 who already have civil rights and 90% of them can engage in all forms of civic activity and decide on manifestations of their citizenship; second, because it examined psychological factors as correlates and predictors of civic activity dimensions, while controlling the influence of all factors.

Though emerging adults already have civil rights, the results showed that their civic activity profile is similar to that of adolescents – they declared the highest level of personal activity, a lower but still high level of passive, and then semi-active citizenship, and much lower involvement in active citizenship related to socio-politic issues. Also, like among teenagers, particular dimensions of citizenship are differently related to psychological factors. Moreover, the correlations with personality constructs and well-being are also similar to those observed among adolescents. These results call for further research on the profile of civic activity and relationships between citizenship dimensions and psychological factors in emerging adults in different cultural and economic contexts to test the universality of the results.The data filled the gap and provided deeper insight into the examined relationships than ‘zero-order’ correlations among emerging adults. They indicate that self-esteem and skills in social exposure situations (as personality constructs) and social well-being are important positive predictors of their propensity to engage in various forms of civic behaviour if all variables are controlled. These results may be helpful for emerging adults who wish to increase their contribution to society, as well as for professionals in citizenship education and policies promoting citizenship activity of young people (emerging adults and adolescents, because they are similar), pointing out that increasing citizenship activity requires deliberate influences and interventions to support and strengthen their self-esteem, social skills in exposure situations and social well-being. Thus, also various factors and interventions that can develop self-esteem, skills in social exposure situations and social well-being of young people may be subject to further research to increase their citizenship activity.

Additionally, longitudinal studies (also including other personality constructs, personal experiences, and objective indicators of civic activity) are needed to better understand the “psychological factors – citizenship dimensions” relationships, as they may be reciprocal. Knowledge of the effects in longitudinal studies will provide clues as to which interventions (directed at the growth of personality constructs, personal experiences or civic activity) will lead to the most positive changes in all variables.