BACKGROUND

Many psychological theories have emphasized the importance of social influence on personal development, which is the process of successive changes taking place within the human psyche. The results of this process are revealed in a given individual’s behavior. The psychological development of any individual person consists of emotional, cognitive, social, moral, and personality aspects. It is most often assumed that the purpose of personal development is to differentiate, organize, and integrate experiences and to achieve internal balance (Bakiera & Stelter, 2011). Interpersonal relationships constitute one of the main factors of this development. Social scientists have attempted to achieve greater specificity by using terms such as social impact, social role, social interactions, or interpersonal relations. All of these refer to how a person lives with and influences others and how he/she is dependent on them. Yet when the social context of personal development is focused on, a certain terminological gap reveals itself as regards the category of the individual who has significant meaning in another person’s psychosocial functioning and whose personality and behavior influence that person’s functioning and development. Thus, the concept of a developmental figure may fill this gap – it refers to an individual who generates a process of developmental changes, i.e., his/her behavior can sustain one’s developmental achievements and/ or change one’s direction of development. Finally, individuals who are not developmental figures do not play a significant role in another person’s development.

Rapid progress in research on life-span development took place after 1980, yet no concepts differentiating interpersonal influence on personal development were introduced. Costa et al. (2019) noted that “traits are important determinants of health, happiness, and generativity; it is worth redoubled efforts to understand how they endure and why they change”, and, it should be added, under whose influence. The influences that determine personality changes come from two general sources, i.e., environmental and genetic. Research has shown that one’s personality changes throughout one’s life cycle via the interaction that takes place between the above influences of the environment and genetics (Baltes & Smith, 2004; Caspi & Roberts, 2001; Funder, 2001; Lerner & Hultsch, 1983). It should also be noted that an individual’s personality is the result of the constant and active interaction that takes place between that individual and his/her social environment. Participating in social interactions allows an individual to satisfy a broad range of human needs – starting with physiological needs in the case of a small child or a disabled person and ending with various psychological needs. Providing for these needs requires the presence of another person. Erikson (1980, 1982) in particular drew attention to the psychosocial aspect of personality development, as he focused on the role played by both society in general and individuals who create significant development circumstances. Perhaps no social group has as great an influence on a person’s development as his/her family, yet relations with teachers, peers, coworkers, sexual partners, and models of leadership are also mentioned as significant relations (Erikson, 1980).

In psychology, the category of the significant other is identified as a key figure in human life. This term was introduced by Harry Stack Sullivan to describe a person whose opinions are of significant meaning for the formation of self-knowledge and identity (Siuta, 2005). I consider interactions with significant others to be pure and deep and to constitute a source of bonds, whereas the influence of developmental figures can also take place in indirect and sporadic contacts. Since I would like to expand on the category of the significant other, which we generally identify with progressive changes, I propose the concept of the developmental figure, as regressive changes and crises can also occur in the development process.

WHO IS A DEVELOPMENTAL FIGURE?

I propose to treat the developmental figure as any individual who shapes the personal development of another person, i.e., this is someone who plays a significant role in someone else’s personal development. How does a developmental figure affect someone else’s development? First, a developmental figure is a source of experiences – those that occur daily, i.e., that are responsible for developmental changes of a cumulative character, and those that are unique, i.e., that constitute turning points in the individual’s development. A developmental figure is a person who contributes to the developmental changes of another person (or of other people). This figure’s influence leaves a permanent trace in a given person’s personality structures and behavior, so without the influence of particular developmental figures a given person’s development would have taken a different course. The presence of these specific figures in a person’s life, as opposed to other figures (persons), defines the specificity of that given person’s individual development.

Developmental figures can be parents, teachers, and caregivers who organize a child’s experiences and give these experiences meaning. They can also be friends with whom a person has long-lasting relationships, although a developmental figure can also be a stranger met only once who, for instance, somehow affects another person’s health, state of possession or his/her previous way of perceiving him/herself. During one’s lifetime, a person is under the influence of various figures who define both the direction and shape of the process of that person’s developmental changes. Most of us are a developmental figure to other, various people, i.e., not only to family members or friends. The greater the scope and strength of the social impact, the more the diversified influence we exert – both in intimate, personal relationships (e.g., with our friends, children) and in formal relations associated with our social roles (e.g., with students, patients). Nevertheless, a configuration is possible where personality development is shaped by developmental figures, but the person him/herself is not a figure to anyone (e.g., a hermit/recluse).

What distinguishes a developmental figure from a person who is not such a figure? First, the intensity, duration, and consequences of the social influence. A developmental figure generates a process of developmental changes, and the entirety of the developmental figure’s influence is not neutral from the point of view of a person’s development. Individuals who are not developmental figures are insignificant to the development of a given person, although relations with them can be (un)pleasant for that individual (e.g., a newly met person on one’s vacation with whom one (dis)likes talking but that person leaves no permanent trace in one’s mind and introduces no developmental changes).

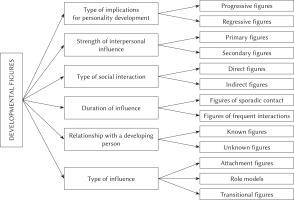

The influence of a developmental figure on the course of another person’s development can take two trajectories: 1) it can modify the existing developmental path (e.g., getting married, which changes one’s current way of functioning), or 2) it can consolidate existing developmental tendencies (e.g., building up a child’s sense of security via the parents’ responsive reactions, or stabilizing a child’s self-esteem via teacher feedback). Both the normative and the atypical course of a person’s development entail being under the influence of a wide group of developmental figures. These figures can be categorized on the basis of various criteria, such as the type of implications they have for personality development, the strength of the influence, the type of social relation, the duration of the influence, the relation to the developing person, and the type of influence (see Figure 1).

CATEGORIES OF DEVELOPMENTAL FIGURES

TYPE OF IMPLICATIONS FOR PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

Progressive developmental figures are people who have a constructive influence on changes in a person’s life, who stimulate and dynamize the course of that person’s development, and who introduce a psychosocial balance. Their influence optimizes development conditions and enables the actualization of a person’s developmental potential. Their pro-developmental influence includes, among others, the following phenomena: support, inspiration, cooperation, control, and demonstrating constructive behavior patterns.

Support is the provision of help in a difficult situation. Someone becomes a figure in someone else’s development because he/she provides a sense of security to that person. This can be done in an emotional, informational, instrumental, material, or spiritual manner. When in contact with a child, what also seems important is evaluative support, which consists in providing feedback to that child regarding his/her behavior. A decisive factor of this support is the quality of the interactions, the aim of which is to reduce the sense of difficulty the supported person might otherwise feel. Another form of progressive influence that developmental figures have on a person is the inspiration they provide, as it encourages one to act (e.g., by intensifying the activity) or directs the person’s actions towards undertaking activities that introduce a new (higher, better organized) level of his/ her functioning. All actions of this kind refer to the phenomenon of social facilitation. The developmental figure, being a facilitator, allows the person to function more effectively, and the figure thus becomes a kind of catalyst for actions that are conducive to a person’s development. As a source of stimulation, the developmental figure plays the role of a guide in the process of one’s learning; for instance, when accompanying a child in his/her play, the developmental figure helps the child seek new ways of using toys and to play in ways that the child might not have known earlier. In turn, in a conversation with an adult, the developmental figure (the adult) can suggest various possible ways of solving a given task. In situations of this kind, this figure does not actively participate in the person’s field of activity but via his/ her actions (e.g., narration, questions, proposals), encourages one to undertake new activities, stimulates that person to increase the efficiency of the actions he/she undertakes, and motivates him/her to achieve more. Another progressive influence is cooperation, in which the developmental figure cooperates with the person when performing a particular action – where the efforts of the two sides are bilateral (centered) and the aim is common. The effects that are achieved together are greater than the results of that person’s individual actions. The cooperation of a child with a developmental figure takes place in an asymmetrical relation, as the adult possesses greater skills than the child. In turn, cooperation in adulthood can be either asymmetrical (e.g., parent – child or superior – subordinate) or symmetrical (e.g., friend – friend, husband – wife). The essence of the developmental figure’s pro-developmental cooperation is the optimal level of his/her sensitivity to the other person’s capabilities. Cooperation is not possible when a person is passive, as it requires decentration, which enables a higher level of performance than when the person acts on his/her own.

The other form of progressive influence is control, which is a situation where boundaries are set for the person’s activity. It consists of exerting influence to make the individual act according to the rules accepted in a given culture or community. Control most often pertains to upbringing situations, thus to the adult–child relation. The adult supervises and makes sure that the rules pertaining to safety, customs, and morality are observed by the child. If a disproportion between the child’s behavior and the norm occurs, i.e., when the child’s actual behavior diverges from behavior that the developmental figure sees as correct, the adult can apply different kinds of sanctions. The role of these sanctions is not only to reduce incorrect behaviors but also to stimulate a gradual transition from external regulation to self-regulation. The essence of this process is one’s internalization of norms and values. The control exerted by the adult often comes up against the child’s resistance and takes the form of negativism on the child’s behalf. As we know, this can mainly be observed between the ages of two and four, and it is associated with the normative crisis of autonomy (Erikson, 1980, 1982). Another period of intensified opposition to adults, particularly to parents, is adolescence, which manifests itself in various forms of teenage rebellion (Oleszkowicz, 2014). In adulthood, personal control is most often inscribed in professional relations and takes the form of formal control (e.g., as regulated by the rules of a given organization). Control in intimate relationships is of an informal character and consists of the exerting pressure of the developmental figure. The last type of progressive influence to highlight here is demonstrating constructive behavior patterns, i.e., presenting behavior that is important from the point of view of a person’s development.

Assuming that regressive changes can also have a developmental value (this happens when they initiate progress), such a form of interpersonal influence in human development also needs to be noted – hence the indication of regressive developmental figures, i.e., people whose influence poses a threat to the successful course of a person’s development. Under their influence, the disintegration of a person’s mental system might take place. Its consequences can ultimately introduce progressive changes, but it can also disrupt the person’s development. The influence of regressive developmental figures basically constitutes a source of experiences characterized by threat, overburden, difficulties, deprivation or trauma. A threat occurs when the developmental figure’s behavior evokes a conviction in a person about an imminent danger to that person (e.g., he/she feels threatened through physical or mental abuse). Overburdening is an influence that generates such an amount and quality of requirements towards the person that it exceeds his/ her capacities (e.g., being overburdened with school or work duties). Difficulties result from the actions the developmental figure takes that introduce various obstacles in the person’s life (and development), such as physical barriers (e.g., a lack of space for learning) or mental barriers (prohibitions, social pressures) – which makes the fulfillment of the person’s developmental tasks either difficult or impossible. The sole effect of the occurrence of difficulties is not synonymous with regress, as difficulties can pose a developmental challenge and can stimulate development. In regressive influence in general there is a level of difficulties that is disproportionate to the person’s resources. Another type of regressive influence is deprivation, where the behavior of the developmental figure may not satisfy the person’s basic needs (e.g., the need for security, acceptance, recognition). Finally, the riskiest form of influence, from the point of view of a person’s development, is the traumatizing influence. These are actions the developmental figure undertakes that introduce extremely difficult situations in the person’s life, and where the person experiences a lack of control over the course of the events (e.g., a car crash, rape). Such events can be caused by individuals who are unknown to the person. The rank of the event and its consequences to the person’s development are such that even a one-time experience with the individual (developmental figure) can have crucial meaning. All forms of physical abuse constitute a significant regressive influence. An example of an extremely negative influence on the part of the developmental figure is parental child abuse, where the adult takes advantage of his/her asymmetrical position in the relationship as it stems from his/her greater strength, power, and skills. The abuse can be physical, psychological, sexual, or economic. The most burdening form of abuse to a child is sexual abuse (Beisert & Izdebska, 2013).

The sole fact of experiencing difficulties, the source of which is the activity of the developmental figure, is not synonymous with a negative impact on the course of development in a person. What is significant is the scale of difficulty, its repeatability, and duration. Permanent regress is a contradiction of development, but temporary regress can be an element of development. What is important is whether there is progress after the regress, so it is important that the regress be of a temporary character.

STRENGTH OF INTERPERSONAL INFLUENCE

On the basis of the strength of interpersonal influence, primary and secondary figures can be distinguished. Primary figures refer to individuals who function in a person’s primary environment, and they are usually members of the family of origin. Secondary developmental figures, on the other hand, influence the person on the basis of patterns formed in the primary environment. A person will come across these secondary figures in kindergarten, at school (teachers, peers), and in the work environment (co-workers, supervisors), but these can also be spouses (partners) in a procreation family.

TYPE OF SOCIAL INTERACTION

Direct and indirect developmental figures can be distinguished based on the type of social interaction. Direct developmental figures are individuals with whom the person comes into direct contact. These are face-to-face or online contacts that are not intermediated by other people. The person’s actions are strictly dependent on these figures’ decisions, e.g., to a child these are the child’s parents, to adults these are friends or partners. In turn, indirect developmental figures are individuals whom the person contacts through other people, through their decisions or directions (e.g., the person’s employer, parliamentarians, authorities, or politicians who introduce legislature regulating how citizens should function in a given country). Both the multiplicity of mediators in the interaction chain and the strength of the influence decide about the person’s level of dependency on a given developmental figure. Both direct and indirect interactions determine the type of experiences a person will go through and, simultaneously, the scope of his/her development. An example in Poland might be the dilemma of a teenage girl who becomes pregnant. Abortion in Poland is generally prohibited, unless the pregnancy is the result of a criminal act or when a woman’s life or health is in danger. Thus, a pregnant Polish teenage girl’s development (and she did not plan to become pregnant at this time) takes place in conditions determined by (previous) decisions of the members of Poland’s parliament – these parliamentarians thus become figures that define the pregnant teenager’s developmental experiences.

DURATION OF INFLUENCE

The duration of a developmental figure’s influence on a person can be divided into sporadic or frequent. Figures of sporadic contacts (or even one-time contacts) are those with whom a person does not interact on a daily basis (e.g., physicians, government employees), and figures of frequent interactions are those a person remains in long-term relationships with (e.g., parents to a child, children to their parents, friends to friends). The strength of the influence is not always in direct proportion to the duration of the interpersonal relation, as sometimes a one-time contact can have key meaning and change the current direction of a person’s development, e.g., a physician might diagnose an illness and prescribe medication that will improve the person’s health or, conversely, a physician’s misdiagnosis might become a source of suffering and physical limitations to a person. In this situation, the physician’s behavior and he/she him-/ herself might contribute to a modification, and sometimes even to a radical change, in a person’s life.

RELATIONSHIP WITH A DEVELOPING PERSON

The above distinction results in a further criterion, namely, the degree to which the developmental figure is familiar to a given person. Here we can distinguish between figures that are either known or unknown to the developing person. The shape of the development also depends on the people a person does not know. This is a wide group of various decision-makers both at a global level (macrosystemic) and at a local level (exosystemic). In particular, the past several years (since 2020) have shown how much people’s development can change after having become infected with the COVID-19 virus. Usually, the source of contact with the virus is unknown, so an unidentified infected individual can also shape the direction of a person’s development.

The last criterion that differentiates developmental figures pertains to the type of impact they have on the developing person. This impact can have a bond-forming, learning, or transitional character.

TYPE OF INFLUENCE

Bond-forming processes are well known in psychology as pertaining to attachment figures, i.e., individuals who evoke strong tendencies in a person who wants to be close to them, particularly in a difficult situation. Bowlby (1988) distinguishes the main attachment figure (e.g., the mother figure/mother) and secondary figures in human development. Factors that decide about who will become an attachment figure are mainly connected with the person’s engagement in interactions and his/her readiness to react to signals. The repeatability of contacts with the attachment figure will lead to the formation of an emotional bond, the foundation of which is one’s being aware that the object of the attachment is available and ready to help, i.e., is the source of a sense of security. Repeated (non-sporadic) contacts with the significant other are crucial for an emotional bond to form. This pertains to both children and adults. Bowlby (1988) notes that although the frequency and intensity of attachment behaviors is the highest in infancy, they do not disappear later in life. In adolescence, attachment behaviors are directed at peers, whereas in early adulthood they are directed mainly at individuals with whom people build intimate relationships (Reis & Patrick, 1996). In late adulthood, they are not only directed at individuals from the same generation but also at representatives of younger generations.

The influence of attachment figures has been described in detail in psychology and continues to be empirically explored. Parents’ responsiveness is a factor that influences the process of shaping the correct bond with a child and reveals a safe style of attachment on behalf of the child (Bowlby, 1988), which will significantly affect the child’s social functioning in later stages of life (Goldberg, 2000). Conversely, the activity of aversive parents will retard the psychological development of a child or will lead to severe psychological disorders in that child (Bakiera, 2016a). Thus, the parents’ actions can stand as a noteworthy predictor of the child’s anxiety and emotional disorders later in adulthood (Chambers et al., 2004). Unfavorable development during pre-parental phases also creates a certain risk, as when parental activity becomes a form of compensation for previous developmental frustrations or failures, it will either limit or impair a child’s functioning.

Mental processes of a different kind are evoked by role models. These are figures who trigger processes of social learning. A role model (from the Latin term modulus – measure, pattern) is a person who has qualities that induce imitation behaviors in the observer (Bakiera & Harwas-Napierała, 2016). Among the role model’s traits or behaviors that are favorable for copying by other people are, first, a high social position, prestige, authority, or the consequences of the model’s actions that are perceived by the observer as positive. A role model is most frequently a person with whom the observer has a strong emotional relationship. Thus, in childhood these are, first, the parents and other caregivers. The behavior of young people is, to a greater degree, also influenced by peers who provide interesting models in the process of identity formation. In adulthood, family members, co-workers, and friends with whom the person spends his/her time have a modeling influence. A role model can manifest an allocentric attitude and can be driven by common good and universal values (e.g., Mahatma Gandhi), but he/she can also be driven by caring exclusively about the quality of his/ her own life, can instigate global conflicts, and negate universal values (e.g., Hitler, Stalin). The influence of a role model takes place through imitation, modeling and identification – all of which are important mechanisms of developmental changes. Functioning, e.g., in a parental role, is subject to strong modeling influences. According to various studies, people who have experienced family violence are less likely to engage in caring for their children and are more often hostile towards them (Gallagher et al., 2009; Levendosky et al., 2006). That is why prevention within this scope should be available to people during pre-parental stages.

The third category of influence as regards developmental figures pertains to periods of transition; in particular this is Levinson’s (1978) concept of the transitional figure who is a mentor who supports the efforts of a young adult in shaping his/her structure of life. The mentor’s activity stimulates, for example, a student’s development by combining activities typical of a teacher, advisor, and guide. According to Levinson, one of the crucial tasks of a mentor is to help define the dream, which constitutes the expected concept of one’s adult life. “A good enough relationship with a mentor” results from a combination of authority and friendship (Levinson, 1978, p. 256), i.e., the student admires the mentor, respects him/her, and is grateful to him/her. Mentors function, therefore, as developmental figures in one’s adult life (Bakiera, 2016b). A mentor is also called “the manager of future generations” (Ponce et al., 2005, p. 1162) because of the role that person plays in shaping the attitudes of the younger generations. The mentor helps the person achieve what he/she would have learned on his/her own but would have done so more slowly, to a poorer degree, or would have failed to have learned anything at all.

The above categories of figures are not disjointed, i.e., progressive figures can be either known or unknown to the developing person and they can have either direct or indirect influence. Analogically, the same applies to regressive figures, as the influence can take place as a result of a one-time interaction with a person from either a primary or secondary environment.

DISCUSSION

This paper deals with how others influence, both via unconscious and conscious means, the formation of an individual’s personality and behavior throughout his/her lifetime. Who then can influence one’s personal development?

Modern social trends have shown that personal development is shaped not only by direct relationships but also by significant online interactions. The contemporary context of human development in Western culture is marked by, among others, processes such as globalization, digitization, and consumerism (Arnett, 2002; Roach et al., 2019; Targowski, 2015; Wani, 2011). These processes have introduced a new specificity of interpersonal relations that affect personal development. It seems that in this context, figures who are either unknown, in indirect contact, or in online contact, and those whom the person contacts sporadically, are extremely important. Globalization and digitalization, in turn, influence the directions of changes in a person’s life not only directly via individuals in direct contact but also via individuals contacted in an intermediate manner online. The emerging globally online social environment has facilitated interpersonal communication. Simultaneously, the promotion of consumer-focused lifestyles and of consumption is also taking place. A significant role here is played by bloggers and vloggers who influence the receivers’ experiences and thus become a new category of significant people. The number of people worldwide who have similar lifestyles, professional ambitions, ways of passing their time, or ways of dressing is constantly rising, as consumerism involves creating or reproducing a particular social identity. Consumers are predominantly influenced by the creators of brands, advertisers, and trendsetters – thus their role in shaping personal development cannot be ignored.

As a result of becoming inhabitants of a truly global village, people acquire similar experiences, discover and identify themselves with similar role models. As pointed out by Harari (2019), consumerism introduces a limitless “sensation market”, i.e., a contemporary person is a consumer of sensations, and this frequently takes place online. For this reason, what seems to be important is the influence Internet users, bloggers, trendsetters, and online retailers have, as these are figures who did not previously interfere in the development of human beings in the 20th century (or did so but only to a small extent), when developmental figures were, first and foremost, family members and those who possessed power.

The conditions of human development in the 21st century have radically changed. Currently, the value of the past is decreasing, i.e., it is ceasing to be a sign-post for social and individual development. The dynamics of current changes that are taking place and the variety of possibilities also influence the future, thus making it difficult to predict. Rapid changeability as a feature of the environment a person lives and develops in, particularly culturally, makes it difficult to indicate what will constitute adaptation to one’s life 10, 20, or 30 years from now. This has consequences for the actions of educators, i.e., individuals who are responsible for updating the developmental potential of young people. Interpersonal pro-developmental actions, including education, have lost their landmark, which until recently was an average, predictable, future environment to live and develop in. Determining the boundaries of developmental equi-potential has thus become extremely difficult. Also, indicating the figures who influenced and shaped an adult’s development requires more caution in formulating hypotheses than simply pointing to parents as mainly responsible for a person’s development. The past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic (as of 2023) have shown, moreover, that development can change its direction dramatically as a result of contact with a COVID-19-infected individual. The consequences of this infection can have, surprisingly, a pro-developmental character and can result, for instance, in one gaining knowledge on how to improve one’s immunity or on habits regarding hygiene, or in caring more about one’s interpersonal relations, but also in re-evaluating one’s sense of life. Focusing on pro-health behavior is a frequent and natural consequence of realizing the fragility of one’s life and when confronting real or symbolic death (TaubmanBen-Ari & Findler, 2005). Yet experiences associated with the COVID-19 pandemic can also disrupt a person’s development, e.g., via a significant decrease in his/her trust in healthcare, the death of a loved one, or difficulties in a relationship with a partner.

Previous research (e.g., Farber et al., 1995; Seibert & Kerns, 2009; Trinke & Bartholomew, 1997; Umemura et al., 2018) has focused mainly or even exclusively on the impact of basic attachment figures. Adding the category of the developmental figure will thus make it possible to expand analyses of interpersonal impact to include people who actually shape human development in childhood and adulthood, and it will allow one to be cautionary to not indicate parents as those solely influencing one’s personal development.

The concept presented here broadly recognizes people who determine one’s personal development. A person who generates a process of developmental changes is not only an attachment figure (which was often taken into account in previous studies). Thus, the category of developmental figure may broaden the spectrum of variables included in psychological research; however, it should be noted that developmental figures are not arbitrary contextual factors affecting a person’s development, as the difference between the inanimate and personal factor of development is fundamental. As a developmental figure, a person influences others in a twofold manner, i.e., the person can control him/herself and choose his/ her actions – all of which will constitute a pro-developmental factor; or the person can limit or hinder the development of others.