BACKGROUND

SHYNESS

Shyness is defined as an as an emotional state, a “discrete emotion” (Izard & Hyson, 1986) and as a personality trait (Cheek & Buss, 1981; Zimbardo, 1977). The oldest documented use of the term shy is as “easy to frighten”. To be shy is to be afraid of people, especially those who are emotionally threatening for some reason: strangers, powerful people, or people of the opposite sex. Shyness is described as a relatively constant tendency to experience tension in the presence of others; it is characterized by inhibition and sense of discomfort in an unfamiliar context (Asendorpf, 1990; Cheek & Buss, 1981). Shyness should not be identified with neuroticism or introversion; it should be treated as an independent dimension of personality (Briggs, 1988).

Shyness is understood as a complex syndrome of symptoms connected with changes in the cognitive, emotional, motivational, and behavioral spheres (Mandal, 2008). Shyness can be identified on the basis of somato-affective symptoms (e.g. blushing, social anxiety), behavioral symptoms (e.g. eye-contact avoidance, avoidance of social interaction, styles of self-presentation), and cognitive symptoms (e.g. anticipation of rejection). Shy individuals experiencing social anxiety experience increased levels of loneliness, and more often display depression symptoms (Dill & Anderson, 1999). According to Carducci and Cheet (2023), shyness includes elevated levels of anxiety (affective/physiological component), excessive negative self-esteem and negative self-preoccupation (cognitive component) in response to real or imagined social interactions that inhibit social activity (behavioral components). There are subtypes of shyness: public and private, situational chronic, and transient (e.g. during periods of changing schools or jobs).

Shy persons have a tendency for negative affect and nonconstructive ways of coping with one’s own emotionality (Eisenberg et al., 1995). Shyness correlates with defensive styles of self-presentation (Bober et al., 2022; Mandal & Wierzchoń, 2019; Schlenker & Leary, 1982), low influence skills (Ericsson, 2018), and Internet addiction (Li et al., 2023), and implies lower relationship satisfaction (Baker & McNulty, 2010; Rowsell & Coplan, 2013).

A significant number of studies have been devoted to children’s and adolescents’ shyness, although shyness is a trait independent of age. There were observed different consequences of shyness in childhood and in adulthood (Zimbardo & Radl, 2023). Their picture differs with respect to gender: shy boys get married and become parents later than bold boys, and achieve professional stability later, while shy girls are more willing than bold girls to follow a traditional family life style, and more often occupied with house-keeping and child-rearing (Caspi et al., 1988).

SELF-ESTEEM

Self-esteem is a reflection of one’s attitude towards oneself (Rosenberg, 1965; Rosenberg et al., 1995), which is relatively stable across the life-span (Baumeister, 1999; Trzesniewski et al., 2003). As a central component of everyday subjective experience, self-esteem plays important psychological functions: it supports tasks and goals, regulates social relations, maintains social position, and deals with mortality salience (Baumeister et al., 2003; Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Leary et al., 1995). Self-esteem is a complex concept which has a global as well as a particular form. The particularity concerns different areas of human functioning. The most frequently mentioned dimensions of self-esteem include: physical attractiveness, vitality, competences, being loved, popularity, leading abilities, self-control, and moral self-acceptance (O’Brien & Epstein, 1988). Self-esteem depends on the subjects’ activity; it reflects their successes and failures in the domains in which their self-esteem is invested (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001).

Crocker et al. (2003) identified seven contingencies of self-esteem: appearance, approval of others, competition, academic achievement, family support, God’s love, and virtue. They noted that generally there are two types of self-esteem contingencies: (a) externally oriented, such as the approval of other people, comparisons with others and the results of competition, physical appearance, academic achievements, and family relationships; and (b) internally oriented, such as moral virtues or God’s love.

SHYNESS, SELF-ESTEEM AND GENDER

Numerous empirical studies show a fundamental role of self-esteem and shyness in the individual’s functioning (Asendorpf, 1990; Cheek & Buss, 1981; Ericsson, 2018; Kernis, 2003; Miller, 1995). At the same time, they indicate that shy individuals have many problems in social functioning, and in establishing and maintaining interpersonal relations (Baker & McNulty, 2010; Doey et al., 2014).

Gender, as one of the central attributes of identity, is significantly linked with self-esteem. Meta-analyses have documented differences in various domains of self-esteem, mostly in favor of men (Gentile et al., 2009; Zuckerman et al., 2016). Gender also differentiates women and men with respect to experiencing shyness, especially in the case of external manifestations of shyness. Women react, more frequently and more distinctly than men, with blushing, eye-contact avoidance and behavioral inhibition (Bruch et al., 1998; Mandal, 2002, 2008). Shyness is more acceptable in women than men, because, according to gender rules, it is perceived as characteristic of women and not of men; men are expected to be ready to perform professional tasks and be more assertive than women. Girls’ and boys’ shyness is evaluated differently by important others: their parents, teachers and peers (Doey et al., 2014; Kingsbury & Coplan, 2012).

CURRENT STUDY

The aim of the current study was to investigate mutual relations of shyness and self-esteem in women. It has been hypothesized that shy women are characterized by lower global self-esteem than bold women. Behavioral inhibition, contributing to the picture of the shy persons’ social functioning, may be a factor significantly disturbing their ability to create their positive self-image. Self-esteem is strongly related to gender, because gender constitutes one of the basic attributes of identity. High self-esteem is significantly more frequently characteristic of men and persons with typically masculine traits (Antill & Cunningham, 1979), while shyness is experienced more intensively by persons with female and undifferentiated gender identities (Bruch et al., 1998; Mandal, 2008).

The study also involves the dimensions of shy and bold women’s self-esteem. One of the fundamental functions of self-esteem is to inform the individuals about the degree of their social acceptance, resulting in building their sense of affiliation (Leary, 1999; Leary et al., 1995). Several studies have shown that individuals with positive self-esteem are more popular and feel greater satisfaction with their relations (Lee & Robbins, 1998; de Bruyn & Van den Boom, 2005). Interacting with others, shy persons often concentrate excessively on their own internal experiences, and on the way their interlocutors perceive them (Pilkonis, 1977). Taking into consideration the fact that shy persons experience social anxiety, one can conclude that other people’s acceptance is highly important for their self-esteem and it probably has an impact on their self-experience.

Establishing and maintaining good social relations constitutes a stereotypically female social role and is fundamental for women’s self-esteem (Eagly & Wood, 2012; Josephs et al., 1992). It was also hypothesized that the dimensions of self-esteem related to women’s relationships and being accepted (being loved, popularity) are more important for shy women than for bold women. Shyness makes the person especially sensitive to other people’s evaluation and their potential rejection. Thus, it may be assumed that shy women’s self-esteem is conditioned to a greater extent by external than by internal factors.

The current knowledge of shyness and self-esteem allows us to assume that shy persons have lower self-esteem than bold persons. This correlation corresponds with patterns of cognitive and emotional functioning displayed by shy persons. However, it has been suggested that as many as 15% of shy persons like their own shyness (Zimbardo, 1977). Perhaps shyness may be positively evaluated by women as a stereotypically female trait. On the other hand, taking into consideration the negative consequences of shyness and the fact that some people consider it to be a neutral trait, one may ponder if there are areas of everyday activity in which shy women evaluate themselves positively, and which of the areas condition their general self-esteem.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

A group of 1020 Polish women, aged 18-73 (Mage = 34.05, SDage = 10.93), took part in the study. 40.9% of the women had completed higher education, 51.7% had completed secondary or post-secondary education, while 7.4% were lower secondary school graduates. 51.3% of the sample reported living in towns with more than 100 000 inhabitants, 30.5% lived in towns with less than 100 000 inhabitants, and 18.2% were rural inhabitants. 49.4% of the examined women were married, 32.5% were involved in an informal relationship, and 18.1% were single.

PROCEDURE

Women were recruited using the snowball method. The group initiating the research comprised women, students of the University of Silesia and other universities of Upper Silesia in Poland. The women first completed the questionnaires themselves and then asked women from their families and friends to complete them. Participation was anonymous, voluntary and free of charge.

MEASURES

Shyness. Shyness was assessed using the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS; Hopko et al., 2005; Polish version: Kwiatkowska et al., 2016; Mandal & Wierzchoń, 2019). The RCBS consists of 13 statements (e.g. “I feel tense when I’m with people I don’t know well”) with the answers from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the current study the reliability was α = .85.

Self-esteem. The Multidimensional Self-Esteem Inventory (MSEI; O’Brien & Epstein, 1988; Polish adaptation: Fecenec, 2008). The MSEI measures global self-esteem, identity integration, defensive self-enhancement and eight components of self-esteem. The eight components of self-esteem are: effectance (competence, power), social self-esteem (likability, lovability), body image (body appearance, body functioning) and self-discipline (moral self-approval, self-control). The scale contains 116 items; e.g. “I sometimes have a poor opinion of myself”, “Most people that know me consider me to be a highly talented and competent person”, “People nearly always enjoy spending time with me”, “I feel that I have a lot of potential as a leader”, “I nearly always feel that I am physically attractive”, “I am sometimes concerned over my lack of self-control”; 1 – it’s not me, 5 – it is me). On all scales, results range from 10 to 50 points; only in defensive self-enhancement results range from 16 to 80 points. The reliability of the subscales was between α = .70 and α = .85 in the current study.

Contingencies of self-worth. The Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale (CSW; Crocker et al., 2003; Polish version: Mandal & Moroń, 2019) was used to measure seven contingencies of self-worth (35 items; 7 × 5 items; 0 – strongly disagree, 3 – strongly agree): appearance (e.g. “My sense of self-worth suffers whenever I think I don’t look good”, α = .52 in the current study), others’ approval (e.g. “I can’t respect myself if others don’t respect me”, α = .55), competition (e.g. “Doing better than others gives me a sense of self-respect”, α = .72), academic competencies (e.g. “Doing well in school gives me a sense of self-respect”, α = .64), family support (e.g. “When I don’t feel loved by my family, my self-esteem goes down”, α = .63), virtue (e.g. “My self-esteem would suffer if I did something unethical”, α = .76), and God’s love (e.g. “My self-worth is based on God’s love”, α = .92). Scores for all contingencies were averaged.

RESULTS

In the group of 1020 women shyness turned out to be negatively correlated with global self-esteem (r = –.58, p < .001). The analysis revealed negative correlations between shyness and likeability (r = –.61), and between shyness and personal power (r = –.56), shyness and academic/professional competences (r = –.55), shyness and lovability (r = –.49) and shyness and body appearance (r = –.49). Shyness was positively corelated with self-worth conditioned by others’ approval (r = .37), God’s love (r = .21), and virtue (r = .08) (see Table S1 in Supplementary material).

The group of shy women and bold women was separated from the research group with the use of the criterion of the 1/2 standard deviation of the sampled mean, i.e. M = 33.41 (min = 13, max = 63), SD = 9.17. Thus, the participants who got an RCBS result equal to or higher than 38 points were described as shy (n = 341), while those who got an RCBS result equal to or lower than 28 points were described as bold (n = 309). Six hundred fifty women were included in the comparative analyses.

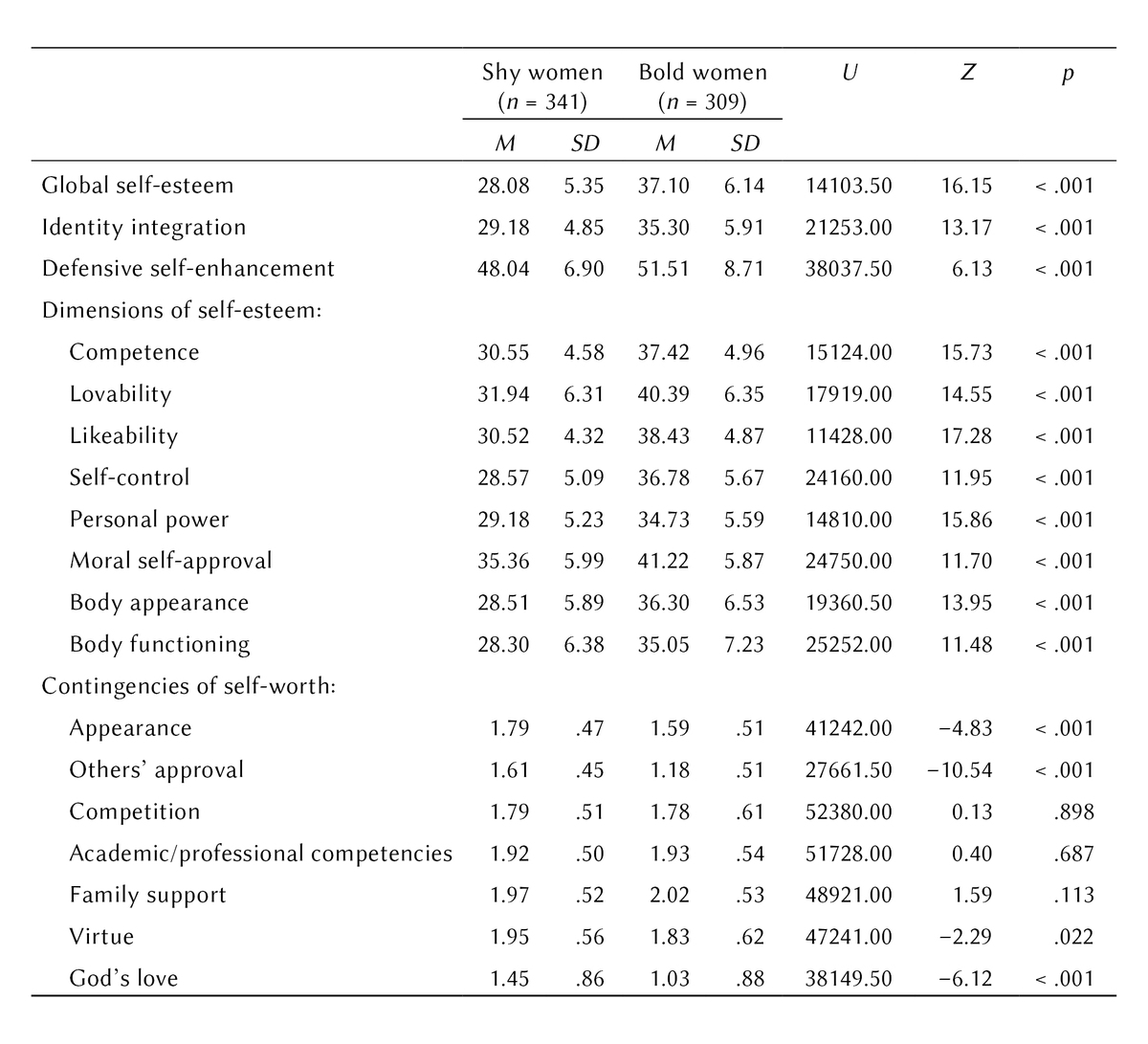

Shy women reported having significantly lower global self-esteem (M = 28.08) in comparison to bold women (M = 37.10, p < .001). Shy women evaluated themselves lower than bold women did in all the dimensions of self-esteem. They also presented a less integrated identity (M = 29.18) than bold women (M = 35.30, p < .001). Shy women also scored lower (M = 48.04) in defensive self-enhancement than bold women (M = 51.51, p < .001).

Shy and bold women alike scored the highest on the scales measuring moral self-approval and lovability, and the lowest on the scales measuring body functioning and body appearance. The study also revealed that both shy and bold women find family support and academic/professional competencies the main contingencies of self-worth, and God’s love was indicated the least.

Among the contingencies of self-worth substantial differences between shy and bold women were observed. Shy women obtained substantially higher scores on appearance (M = 1.79) compared to bold women (M = 1.59), others’ approval (M = 1.61) compared to bold women (M = 1.18), virtue (M = 1.95) compared to bold women (M = 1.83), and God’s love (M = 1.45) in comparison to bold women (M = 1.03, p < .001) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Dimensions of self-esteem and contingencies of self-worth of shy women (n = 341) and bold women (n = 309)

The results of multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis showed (R = .74, R2 = .55, F = 77.00, p < .001) that predictors of shyness in the research group were self-esteem related to likeability (β = –.29), personal power (β = –.29), lovability (β = –.14), body functioning β = –.10), and contingencies of self-worth predictors of shyness based on others’ approval (β = .14), God’s love (β = .12) and academic/professional competencies (β = .07). Age, marital status, relationship length, and place of residence (village, city, large city) were not predictors of shyness. Only women’s education, vocational more than higher education, turned out to be a weak predictor of shyness (β = –.20, p = .030) (see Table 2).

Table 2

Multiple linear regression results. Shyness and self-esteem (N = 1020 women)

DISCUSSION

The study showed that in women there is a strong relation between self-esteem and shyness in women. The results confirmed the hypothesis that shy women have significantly lower global self-esteem than bold women. Shy women also have significantly lower self-esteem in comparison to bold women in all analyzed dimensions. In addition, shy women are characterized by lower identity integration, which indicates that their self-esteem is less coherent, and that they can experience incompatibility or conflict between different components of their self-esteem. Differences were also observed in defensive self-enhancement, which shows that bold women present a greater tendency to control their self-esteem than shy women.

According to the hypotheses, the strongest predictors of shyness turned out to be self-esteem conditioned with interpersonal relations: likability, personal power, lovability and body functioning. It was found that with the decrease in the level of self-esteem in these dimensions of self-esteem the level of shyness increases.

This result may be explained by the importance of the female social role connected with interpersonal interactions. However, it is worth mentioning that social acceptance is perceived as significantly more important for self-esteem conditioning in shy women than in bold women. Shyness, generating failures mainly in establishing and maintaining social interactions, may make this area crucial for the self-esteem of shy women. This, in turn, amplifies shyness and maintains low self-esteem in shy women. It is also possible that a lack of success in interpersonal contacts is related to a lack of success in other activities (e.g. it does not provide the opportunity to achieve success in other areas, and, as a consequence, maintains low self-esteem and shyness).

The results indicating global self-esteem and all componential self-esteem in shy women, especially in likeability, lovability, personal power, body functioning and self-worth conditioned by others’ approval, may be justified in the context of self-esteem functions, where one of the important functions is monitoring of the level of the individual’s social acceptance (Leary et al., 1995). Shyness is related to interpersonal problems and low social skills, which may constitute a significant determinant of self-esteem and a barrier to enhancing women’s self-esteem. The current research results suggest, however, that the positive stereotype of a shy woman and greater social acceptance of shyness in women than in men do not minimize the negative consequences of women’s shyness in global self-esteem and its dimensions. It can be assumed that the interpersonal functioning of shy women is significantly hampered by their shyness.

Contingencies of self-worth related to God’s love was identified as one of the predictors of shyness. Religion is a reference point in the self-esteem of a shy person. Religion constitutes a point of reference in self-evaluation for a shy person. God’s love may provide people with a sense of security and acceptance. Social norms related to religion also determine the framework of interpersonal behavior for women and men.

The research was conducted in Poland, where the majority of the population are religious people – Catholics. In Polish culture, and in the Catholic religion, feminine and family values (e.g. the cult of Mary, the Polish Mother) are highly valued. According to some researchers, Poland can be described as a feminine culture (Boski, 1999). Modesty is a highly valued trait, especially among women in Poland (Dabul et al., 1997), often associated with reserve and shyness. Therefore, modesty fits the image of a shy woman. It can be speculated that the shyness of women may be related to their greater religiousness.

Poland is a more collectivistic than individualistic culture (Boski, 1999). Cultural explanations of shyness suggest that personality factors related to shyness, such as lowered self-esteem of interpersonal competence and rejection expectation, are experienced to a greater extent in collectivist cultures and place greater constraints on individual expression than in Western cultures, which are more individualistic and allow for greater tolerance of individual expression. Cross-cultural comparisons of shyness tend to focus on differences between Western (i.e. the United States) and Eastern (i.e. Asian) countries and report more shyness in Eastern cultures (approximately 60%) than in Western cultures (approximately 40%) (Carducci & Cheek, 2023).

There are some limitations to the study. At first, the research did not analyze the type of interpersonal activity of women in the private (family, friends, partners) and public (school, university, workplace) spheres. It can be speculated that professionally active women are less shy because they have experience in dealing with shyness in the workplace; on the other hand, professionally active women may experience more negative consequences of their own shyness in situations requiring social exposure necessary in professional work. The type of work related to direct contact with people or online work also seems to be important.

Secondly, the degree of acceptance of the traditional female stereotype was not examined. There are probably also generational differences in the acceptance of women’s traditional roles. Women who highly accept traditional female roles may be more positive about their own shyness than women who value less traditional roles. The relationship between shyness and self-esteem in such women may not be so negative.

Thirdly, the research was conducted in Poland, where the majority of the population is religious – Catholics. In future is also worth analyzing the relationship between religiousness and shyness of women in different religions and cultures. It is also important to consider the degree of acceptance of the traditional stereotype of women in different cultures.

Supplementary material is available on journal’s website.