BACKGROUND

Psychologists emphasize the importance of positive work-related psychological mechanisms affecting employees’ health and performance. They indicate that a change-capable, competent employee is able to cope with the demands of the job and support the growth of the organization (Robledo et al., 2019). However, in some types of organizations, such as prisons, due to their administrative-formal nature, it is more difficult to notice and promote autonomous employee initiatives adopted to increase work efficiency among orders, service orders, and rigid procedures of conduct. The Prison Service is a hierarchical and formalized formation, confronting officers with stressful events, often threatening life and health. Prison work is one of the most difficult and demanding professions. It is characterized by the authoritarian nature of the superior-subordinate relationship, demanding duties, performed with exposure to dangerous behavior of prisoners or the requirement to have special skills to take care of mental well-being despite the hardships of the service. Psychological literature on prison work mainly emphasizes work environment deficits, restorative conditioning (Sygit-Kowalkowska et al., 2017), and the theme of work psychopathology. A review of articles on work psychology in leading American journals contained information about negative effects of working in prisons. Prison officers (PO) are responsible for rehabilitation, education and management of inmates, maintaining security and order in prisons, exposing themselves to mental health disorders (Obidoa et al., 2011). Being with inmates isolated from society because of their crimes usually means working with demoralized, aggressive people with negative attitudes towards others, which puts serious mental burdens on officers and raises the risk of diseases, increased irritability, feelings of tension, depression, and addictions. Polish literature on the subject reveals the same facts (Sygit-Kowalkowska et al., 2021). The costs incurred by prison staff are visible, despite the fact that selected candidates with very good psychophysical health are admitted to the Prison Service. Prison officers make attempts to cope with the job demands by using personal resources to enhance their own effectiveness and engagement. It is important to support them in their efforts to build positive relationships at work and adapt organizational policies to daily tasks, to increase the level of meaning of work, quality of life, satisfaction (Piotrowski, 2012) and well-being, which are positive mechanisms of adaptation to work conditions. These issues are close to positive psychology, which emphasizes that work can be a source of happiness, sense of meaning, personal development and self-realization for a person (Kasprzak et al., 2017). Focusing on improving POs’ competencies, building resources, commitment, and shaping pro-social behaviors for enhancing the sense of fulfillment at work seems to be an innovative direction for training the staff of the Polish prison system, as evidenced by this study. The analysis according to the Job Demands-Resources Model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) is quite a popular approach to behavior at work. According to this, work behaviors are derived from a specific game of resources and demands. The job demands-resources theory (JD-R theory) groups factors in the work environment into two categories: demands and resources, determining how they interact with individual well-being and functioning at work. Demands, also called requirements, are the physical, psychological, social, and organizational aspects of work that create the need for physical or psychological effort to cope with them. Resources help to achieve goals, cope with demands, stimulate development and learning. Researchers (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) highlighted work resources such as autonomy, availability of feedback, social support, development opportunities (Piotrowski et al., 2020a) and personal resources (personality traits, sense of efficacy, self-esteem, optimism). This article focuses on the relationship between personal resources understood as personality traits of prison officers and types of applied job transformation strategies – job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), work engagement and work well-being (Schmutte & Ryff, 1997).

The term personality includes ways of behavior that are typical of a person and that are universally revealed in any life and situational context. One of the most popular concepts of personality is the Five Factor Model of Personality (FFM), in which a “trait” is understood as a predisposition for a person to behave in a certain way (Porczyńska-Ciszewska & Kraczla, 2017). The basic dimensions of personality are formed by neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The neuroticism dimension denotes the intensity of negative emotions experienced and straddles the poles of adjustment and emotional imbalance. High neuroticism scores indicate vulnerability to emotions and low self-esteem, while low scores indicate self-confidence. Extraversion refers to an individual’s typical social interactions, activity level, energy, and ability to feel positive emotions. High scores indicate a person who is assertive, more confident, and seeks interaction with people, while low scores are associated with seeking solitude. Agreeableness indicates an attitude toward others in terms of compassion and cooperation. Low scores of agreeableness mean suspicion, competitiveness, and challenging. High scores of agreeableness mean naive and submissive. Conscientiousness refers to action, perseverance, diligence, and compliance (DeYoung et al., 2007). Openness is the search for new experiences and their value, tolerance for novelty, and cognitive curiosity, which is related to intellect as a synonym of mind (Czarnota-Bojarska & Andersz, 2020). The FFM is the dominant approach to the basic dimensions of personality in the literature, but it raises doubts among many researchers, and criticism from theoretical and methodological positions mainly concerns the number and structure of the personality factors extracted. In this study the structure of personality stems from different research traditions (lexical and psychometric), which show a certain coherent picture of the five basic dimensions of personality: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability (vs. neuroticism), and intellect or openness to experience (Strus et al., 2011). This study used a description of personality traits established by a team of researchers led by Cieciuch (Topolewska et al., 2014). Higher levels of work engagement were observed in connection with higher level of extraversion, positive correlations with conscientiousness and negative correlations with neuroticism (Langelaan et al., 2006). Another result of the research on personality at work is highlighting the associations of conscientiousness with engagement, indicating extraversion and openness to experience as less significant predictors of it (Akhtar et al., 2015). This is partially supported by other results showing that emotional stability and conscientiousness independently accounted for most of the variance in work engagement, suggesting that employees who are engaged in their work are more emotionally stable, socially proactive, and achievement-oriented (Roberts et al., 2005). In other analyses, extraversion and agreeableness have shown weak relationships with engagement (Chirkowska-Smolak & Grobelny, 2015). Meta-analyses of the associations of personality traits with job functioning show that job performance is not fostered by neuroticism, and conscientiousness is associated with job performance (Czarnota-Bojarska & Andersz, 2020). The reason for the inconsistencies in research reports may be that a person’s behavior at work depends on the interaction between his or her personality and the work environment in which he or she has opportunities to express attitudes, values, and use competencies. These inconsistencies point to the need for further research on the relationship of personality traits with behavior and well-being at work, with particular attention to the demands of the prison work environment. It is interesting to see how officers behave at work in the conditions of a specific, formalized environment, where self-expression, expression of opinions, and use of personality-determined ways of doing things face organizational barriers, yet employees take actions to improve their work. It is therefore particularly important to examine the key phenomena postulated by positive work psychology: job crafting, job involvement, and feelings of well-being.

Job crafting (Tims & Bakker, 2010) is a form of building work engagement through active participation of the employee in shaping the work environment according to his/her needs. Job crafting consists in adjusting aspects of work to personal needs and capabilities, in which the employee takes over the responsibility for feeling good at work by restoring the sense of work meaning related to the tasks performed. The first step of a successful job crafting strategy is to change tasks, e.g. “it is I who can find my way, I don’t have to wait for my supervisor’s help...” (Roczniewska & Bakker, 2016). To define the phenomenon of job crafting, Tims and Bakker (2010) use the JD-R model, indicating that four types of actions are taken to foster person-job fit, job satisfaction, job meaning, and engagement: increasing structural job resources, increasing social job resources, increasing challenging demands, and reducing impeding demands. The feedback between job resources and personal resources is the essence of job transformation (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), as employees with access to sufficient job resources can increase job demands without suffering negative psychological consequences. When demands make it difficult to achieve job goals, employees engage in activities that reduce demands to match their resources. Conversely, when job demands are too high, employees can increase resource levels through feedback or by actively seeking the support of others (Tims & Bakker, 2010), which results in maintaining an appropriate level of work motivation (Salanova et al., 2010). To balance job demands and resources with personal abilities and needs, employees engage in job crafting, which results in increased satisfaction and reduces the risk of burnout and increases employee performance and productivity (Tims et al., 2013, 2015). The employee, as a result of job crafting, creates optimal work conditions (physical or cognitive changes made to the task or the relationships between elements of his or her job) to increase engagement and a sense of meaning in what he or she does (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Job crafting encompasses three areas of modification: tasks, relationships, and perception of work. Task modification (task job crafting) refers to changing the number, scope, and type of job tasks to make more use of one’s strengths. Relational job crafting refers to changes in the quantity and quality of interactions with others. It involves increasing/reducing the frequency of contact and rearranging work to reduce the intensity of toxic friendships that make little contribution to daily work functioning, but often require extra time and commitment. This is especially important when performing work under pressure, such as in the prison industry. In contrast, transforming relationships or tasks can occur after a prior redefinition of the goal and its meaning for the employee (cognitive job crafting), as a result of changing beliefs about work (Rogala & Cieślak, 2019). Job crafting is therefore a product of employee dispositions (e.g., curiosity, flexibility), situational and organizational conditions (e.g., autonomy), and job characteristics (e.g., task difficulty). Job task interdependence decreases the frequency of job crafting because it implies less freedom to organize one’s work, whereas job freedom increases job crafting because employees perceive more opportunities as fitting (van Wingerden et al., 2017). Therefore, with respect to personality traits, one would expect a relationship between extraversion and conscientiousness with increasing structural and social resources and with increasing demands (Kooij et al., 2017), hence H1: There is a relationship between personality traits and job crafting.

H.1.1. The higher the extraversion, the higher the intensity of job crafting.

H.1.2. The higher agreeableness, the higher the intensity of job crafting.

H.1.3. The higher the conscientiousness, the greater the intensity of job transformation.

H.1.4. The higher the emotional stability, the greater the intensity of job transformation

H.1.5. The higher the intellect, the greater the intensity of job transformation.

Work engagement is an important mediating mechanism between work environment conditions and employee behavior (Czarnota-Bojarska, 2010), which involves attitudes toward work, giving with passion and dedication, creating bonds between employees and the organization, intensifying attention and time spent thinking about work, intensity of role fulfillment, amount of effort put into work, and intellectual and emotional engagement in the organization (Piotrowski et al., 2020a). Engaged employees are motivated to devote energy to perform work tasks; hence researchers (Bakker et al., 2011) defined work engagement as a positive, satisfying, affective-motivational state of work-related well-being. Work engagement is related to initiative, higher job performance, commitment to the organization, innovation, higher goal orientation, organizational citizenship behavior, creativity and sharing of knowledge with coworkers (Piotrowski et al., 2020b). It has a negative impact on absenteeism and turnover intention and is a negative predictor of health problems. Thus, the attitude or behavior of work engagement is desirable within the prison service. Related studies reported health consequences of workplace bullying, and, as we know, the prison environment contains negative phenomena. According to Schaufeli and Bakker (2010), work engagement involves dedication to the organization, especially emotional, and the manifestation of behavior directed toward increasing the organizational effectiveness, hence the distinction between three components of engagement: vigor, absorption, and dedication. Vigor is understood as persistence, energy, and willingness to put effort into work, having meaning between the demands of work and resources in coping with difficulties. Absorption is the state of being focused on work with loss of time control, efficiency, and the ability to cope with difficult situations and solve problems more efficiently, which in turn translates into a reduction of tension at work. Dedication occurs when an employee cares about work; finds it important, purposeful, inspiring, and challenging; and feels pride in the tasks at hand. The following job resources are positively related to commitment: skills, learning opportunities, support from coworkers and supervisors, and performance feedback (Salanova et al., 2010). In relation to personality traits, engagement is related to activity and energy for action, while at the same time it fits into the more active and energetic aspects of personality such as neuroticism and extraversion. People who are independent in their choices, actively shaping their living environment, and initiating change, are more successful in increasing work engagement (Seibert & Kraimer, 2001). In the FFM, each component of engagement is associated with slightly different personality traits. First, one can assume the existence of a relationship of high dynamism and energy in behavior between extraversion and vigor, where the intensity of extraversion co-occurs with higher levels of vigor, and even more interesting is the demonstration of this relationship in prison workers, as a specific occupational group, where one can expect a relationship of vigor with conscientiousness and agreeableness. Conscientious employees will be more dedicated, exemplary, and will put more energy into their work. Emotional stability, which promotes better functioning, will correlate positively with vigor. Preoccupation, understood as forgetfulness and absorption, will be related to conscientiousness. A negative relationship between extraversion and preoccupation can also be expected, because more extraverted workers are mobile, change activities and tasks, need social contacts, and thus find it more difficult to be deeply involved in the current task. Conscientious workers are more likely to apply themselves to their work, and hence can be expected to have a higher level of dedication. At the same time, it can be assumed that agreeableness will be associated with higher levels of preoccupation, where this assumption is based on the important role of cooperation and friendliness in task completion. Emotional stability does not seem to be conducive to preoccupation, which requires losing distance from work. Dedication will be associated with conscientiousness, because in defining this trait it is emphasized how much importance the employee attaches to their duties. Agreeableness is another personality trait that can be suspected to be related to dedication, because agreeing with the priorities set by the organization and tending to identify with the organization will lead to stronger dedication to work. A characteristic of extroverted workers is their high need for stimulation, so work that is stimulating (challenging, which is what prison work is) will generate an increase in the dimension of dedication in prison workers (Xanthopoulou et al., 2013). Considering the fact that personality traits are revealed regardless of the situation, we have grounds to formulate H2: There is a relationship between personality traits and work engagement.

H.2.1. The higher the extraversion, the higher the work engagement.

H.2.2. The higher the agreeableness, the higher the work engagement.

H.2.3. The higher the conscientiousness, the greater the work engagement.

H.2.4. The higher the emotional stability, the higher the work engagement.

H.2.5. The higher the intellect, the higher the intensity of work engagement.

The concept of well-being refers to the beneficial elements of the situation in which a person finds themselves and refers to a person’s assessment of life involving cognitive judgments and emotional responses to events (Czerw, 2017). It is a construct that includes elements of: positive emotions (happiness and satisfaction with life), absorption, meaning (a sense of belonging to something we recognize as greater than ourselves and willingness to serve it), positive relationships with people, and achievement. It is an evaluation of one’s work life in relation to the content of work and the work environment, related to a sense of meaning in work and the value of work, which touch on self-image, life and functioning as an employee, and less on a positive emotional balance. A higher level of well-being is associated with job satisfaction, a sense of security and belonging to a group or organization, a sense of value, opportunities for development and self-actualization, and reductions in stress and its health consequences, costs associated with employee turnover, and sickness absenteeism; it also makes it easier to implement change and innovation (Czerw, 2017). Researchers point to the existence of several dimensions of well-being: the psychological dimension (job satisfaction, self-esteem and capabilities), the physical dimension (physical job security, health care) and the social dimension of well-being, referring to the quality of relationships with other people, trust, social support and cooperation (Grant et al., 2007). The impact of well-being on organizational performance (Jain et al., 2009), stress management, and job burnout has been confirmed (Jones et al., 2010). Regarding the relationship between personality traits and well-being, it has been pointed out that happy people are characterized by certain constant psychological features. A relationship of well-being has been shown with scores of neuroticism-emotional stability, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, self-esteem, activity level, and sense of mastery over one’s destiny. The highest levels of well-being at work and in life are achieved with compatibility with values and the ability to realize one’s own potential, which may be biased by the value judgments of the personality and well-being scales, but after eliminating the influence of the value effect, the Big Five remains a significant predictor for all dimensions of well-being examined (Schmutte & Ryff, 1997).

Thus, we conclude that despite difficult situational factors, prison officers with higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness will experience greater well-being, and those who are unstable (neurotic) will experience less well-being. In the case of conscientiousness, the relationship may be more complicated, i.e., situational factors that make it difficult to perform at high levels will moderate the relationship between this personality trait and feelings of well-being because strong barriers will prevent them from being conscientious. Here, employees may engage in activities that increase job resources, which would enable them to feel well-being, and one such strategy is job crafting. This leads us to formulate hypothesis H3: There is a relationship between personality traits and well-being in prison workers.

H.3.1. The higher the extraversion, the higher the level of well-being.

H.3.2. The higher the agreeableness, the higher the level of well-being.

H.3.3. The higher the conscientiousness, the greater the level of well-being.

H.3.4. The higher the emotional stability, the greater the level of well-being.

H.3.5. The higher the intellect, the greater the level of well-being.

There exists a relation between job crafting, work environment, performance, and the adaptability of officers, who are able to enhance crafting behavior for a healthy balance of work resources and challenges through flexible and creative coping with problems and unpredictable situations in prison. This may provide evidence that organizational perception is an extremely important variable affecting the development of individual employee performance at work, similarly to well-being. Expanding opportunities for autonomous participation of employees in decision-making to improve their work and take care of their well-being and the ability to influence their own career path and professional development influences the improvement of the ability to cope with prison work by using engagement and job crafting strategies. The role of organizational support here appears to be a key factor in initiating job crafting and work engagement to achieve officers’ career goals (Park et al., 2020). This study aimed to explain psychological determinants of job satisfaction in terms of organizational structure, specifically, among penitentiary staff working in various prison departments. In this study, the impact of personality traits and proactive job crafting strategies, strategies for increasing engagement and well-being were also analyzed. Furthermore, the authors attempted to answer the following study questions:

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Two hundred and eighty prison officers (PO) of Polish Prison Service in total, aged 22 to 52 (M = 36.60, SD = 5.59), participated in the study; 26% were women. Participants were differentiated according to the work corps and departments: 39% were assigns (n = 109), 37% (n = 103) were non-commissioned officers and 24% were from the officers’ corps (n = 68). Participants’ length of work did not exceed 15 years (M = 14.17, SD = 6.08); years of work in the Prison Service not exceeded 10 years (M = 9.80, SD = 4.54). Detailed information concerning participants is presented in Table 1. Sociodemographic data did not statistically significantly affect the evaluated variables. The study was accepted by the Polish Prison Service policy makers. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (decision: KEBN 38/2021). Prison officers’ randomized recruitment was conducted using the pen-and-paper method. The study was voluntary and anonymous. Before participation, each individual received the information on the purpose of the study and its procedure and gave their informed consent to participate. The procedure involved completing surveys on personality, job crafting, work engagement, well-being and a sociodemographic questionnaire prepared for this study’s purposes.

Table 1

Characteristics of participants (N = 280)

MEASURES

Given the nature of the respondents’ work environment and the selection of variables, in the study we used a set of questionnaires with proven psychometric values: the IPIP-BFM-20, the Job Crafting Questionnaire, the Workplace Well-being Questionnaire, the UWES-9 and the authors’ questionnaire.

International Personality Item Pool – Big Five Markers-20 (IPIP-BFM-20). The “personality” variable was measured using the IPIP-BFM-20 (Topolewska et al., 2014), the short questionnaire for measuring the Big Five. It is a shortened version of the IPIP-BFM-50 in Goldberg’s lexical model, where, based on the FFM in the Polish sample, it indicates a more culturally appropriate intellect, which is related to openness. The questionnaire contains 20 items in five subscales: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect. Respondents answer on a five-point scale. Cronbach’s α for the subscales was: extraversion .78, agreeableness .71, conscientiousness .75, emotional stability .70, intellect .65.

Job Crafting Questionnaire (PP; Roczniewska & Retowski, 2016), selected for its good psychometric indices, measures the level of job crafting. It contains 21 items in four subscales: increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, increasing challenges and avoiding demands. Respondents answer on a five-point scale. Cronbach’s α for the whole questionnaire is .78, and for the subscales: increasing structural resources .83, increasing social resources .67, increasing challenges .84, and avoiding demands .75.

The Workplace Well-being Questionnaire (KDMP; Czerw, 2017) contains 44 items in four subscales: positive organization, job fit and development, positive relationships, and contribution to organization. Respondents answer on a seven-point scale. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the whole questionnaire is .92 and for the subscales: positive organization .90, job fit and development .93, positive relationships .93, contribution to organization .91.

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) measures work engagement. It consists of 9 statements, rated on a seven-point scale in relation to three subscales: vigor, absorption and dedication. Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient for the whole questionnaire is .94 and for the subscales: vigor .92, dedication .93, absorption .94.

PROCEDURE

The surveys were collected when respondents participated in mandatory skills training in Szkoła Wyższa Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości in Warsaw. The measurements were administered to the participants in one session by the researchers. Before participation, the researchers informed the participants about the purpose of the study, procedure, anonymity of the results, and they received consent to participate. A total of 280 prison officers were asked to fill in and completed the data sets; 11 participants data were rejected due to incorrect completion of questionnaires.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s r correlation coefficients and multiple hierarchical regression analysis with the backward method, preferred in order to eliminate suppressor effects (Field, 2013), were conducted via SPSS 25.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

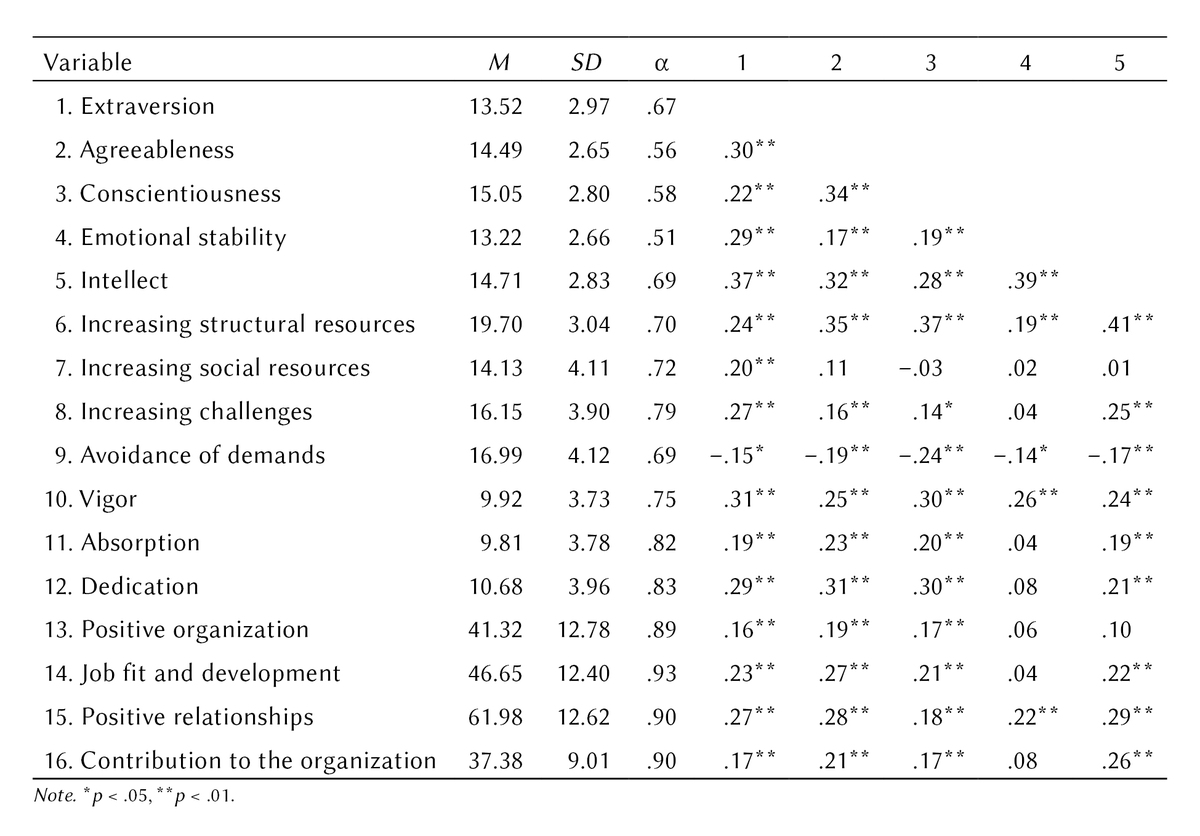

In the first step correlation coefficients were calculated for all variables (Table 2). The data from the correlation analysis showed interesting relationships between the explanatory variables, but these were not described due to the discussion of the regression analyses used with semi-particle correlations (ra(b,c)) as a more advanced statistical method indicating more accurately the strength of the relationship between the variables.

Table 2

Correlations and descriptive statistics for all the variables of the study

The regression equations of the associations of personality traits and job crafting strategies presented in Table 3 proved to be statistically significant; however, the amount of variance explained only for increasing structural resources was significant (26%; F = 20.20, df = 5, p < .001). This job crafting strategy is significantly explained by intellect (β = .28, p = .001, ra(b,c) = .24), conscientiousness (β = .22, p = .001, ra(b,c) = –.21), and agreeableness (β = .19, p = .01, ra(b,c) = .16). In all of these cases, their higher trait intensity is associated with a higher score for using strategies to increase these resources. 10% of the variance in the use of the increasing challenges strategy was explained by personality traits (F = 6.91, df = 5, p < .001). Here again, in both cases, higher levels of extraversion and intellect are associated with higher levels of strategy use (β = .21, p = .01, ra(b,c) = .19 and β = .19, p = .01, ra(b,c) = .16, respectively). For this analysis, it is worth noting one more relationship that, although it did not reach the level of standard statistical significance, carries interesting information. This concerns the trait emotional stability, whose higher intensity (β = –.11, p = –1.69, ra(b,c) = –.09) is accompanied by a lower level of use of the strategy of increasing challenges, so it can be inferred that stable people try not to increase the demands of their work. The regression equation for the strategy of avoiding requirements explains only 7% of the variance, but carries important content, as only the trait conscientiousness is significant (β = –.17, p = .01, ra(b,c) = –.16), and the results indicate that conscientious prison workers are less likely to lower their level of requirements at work than their less conscientious colleagues. The least amount of variability was explained in the equation whose explained variable was the strategy of increasing social resources (4%; F = 3.37, df = 5, p < .001), indicating a relatively strong influence of other, non-personality variables. The only personality trait significantly associated with this strategy is extraversion (β = .22, p = .01, ra(b,c) = 20). Employees with higher intensity of this trait improve their work situation by increasing social resources. The regression equations recorded in Table 4 explaining the variable work engagement using personality traits proved to be statistically significant and the magnitudes of explained variance for vigor (17%; F = 12.2, df = 5, p < .001) and dedication (16%; F = 11.8, df = 5, p < .001) proved to be more significant than absorption (8%; F = 5.8, df = 5, p < .001). Vigor is significantly explained by conscientiousness (β = .18, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .17), extraversion (β = .18, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .16), emotional stability (β = .14, p < .05, ra(b,c) = .13) and agreeableness (β = .10, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .09). In all these cases, their higher intensity is associated with higher scores on the vigor scale. Slightly less, 16%, of the variance in the variable dedication was explained by personality traits. In this case, the intensity of the variables conscientiousness (β = .20, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .18), extraversion (β = .19, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .17), and agreeableness (β = .18, p < .05, ra(b,c) = .16) were associated with higher levels of dedication. The analysis shows that agreeable and conscientious employees are more dedicated to their work, care about their work, and see the purpose of the difficult tasks they perform. In Table 5, the regression equations of the relationships of personality traits and well-being at work were found to be statistically significant and the amount of explained variance was highest (14%; F = 9.75, df = 5, p < .001) for the variable positive relationships followed by job fit and development (11%; F = 7.83, df = 5, p < .001). For positive relationships, the relationship was shown by agreeableness (β = .17, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .15), extraversion (β = .13, p < .05, ra(b,c) = .11), and intellect (β = .17, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .13). Agreeableness and extraversion were significant for job fit and development (β = .17, p < .01, ra(b,c) = .16 and β = .13, p < .05, ra(b,c) = .12, respectively). For contribution to the organization (8%; F = 5.74, df = 5, p < .001), only intellect was found to be significant (β = .20, p < .001, ra(b,c) = .17). The trait agreeableness explained the least (4%; F = 3.36, df = 5, p < .01) of the variance in the positive organization variable (β = .12, p < .05, ra(b,c) = .11). More agreeable employees rated the positivity of the organization higher.

Table 3

Coefficients of regression equations explaining job crafting by personality traits

[i] Note. **p < .01, ***p < .001; df = 5. The semantic aspects are as follows: increase structural resources (ZZSTR), increase social resources (ZZSP), increase requirements (ZW), avoid challenges (UW). The personal dispositions are as follows: extraversion (E), agreeableness (U), conscientiousness (S), emotional stability (SE), intellect (I).

Table 4

Coefficients of regression equations explaining work engagement by personality traits

Table 5

Coefficients of regression equations explaining work well-being by personality traits

[i] Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; df = 5. The semantic aspects are as follows: positive organization (PO), job fit and development (DIR), positive relationships (PR), contribution to the organization (WWO). The personal dispositions are as follows: extraversion (E), agreeableness (U), conscientiousness (S), emotional stability (SE), intellect (I).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the direct relationship between personality traits and job crafting, work engagement, and work well-being of prison officers. It was found that personality traits influenced behavior at work in the prison officer population (Peral & Geldenhuys, 2020) and helped to understand what is the importance of personal resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) in the process of reducing the demands of the work environment, building engagement and well-being through the use of job crafting strategies. In relation to job crafting (H1), the key personality traits influential in increasing structural resources were agreeableness, conscientiousness, and intellect. Agreeableness is important when required to perform work that requires high levels of social interaction (Peral & Geldenhuys, 2020) to be caring and emotionally supportive, and so was engagement extraversion, as confirmed by the results. Conscientiousness and intellect have been shown to be of key importance in increasing structural resources, productivity and efficiency at work, as employees are able to redefine the purpose of their own work, to be punctual, well organized, careful and accurate, which consequently makes prison work more meaningful. A higher level of conscientiousness results in a decrease in the avoidance of demands, the logical reason for which is the persistence in giving of oneself everything at work and the desire to perform the task at a satisfactory level without seeking facilitation. Extraversion and intellect are important in terms of engaging in interpersonal relationships, extra tasks, and helping behaviors (Tims et al., 2015). Emotional stability did not show any relationship with job crafting, although a tendency to experience negative emotions and behaviors could be expected when exposed to high job demands, but this may be related to the outcome of prison recruitment and selection procedures eliminating emotionally unstable individuals. Additionally, strict procedures and procedure manuals (Mansell et al., 2006) may have the effect of limiting employees’ expression of emotional instability, resulting in a lack of discernible relationship. This bodes well in the context that this work requires efficiency and emotional adjustment rather than impulsivity and vulnerability. The important trait that emerged as most relevant to job crafting appeared to be intellect, which in the FFM would be openness to experience or what is also known as culture or creativity. It is all about open-mindedness because with intelligence, employees have broad interests and imagination and by liking to explore new things, they are able to support themselves with job transforming strategies. Another study (Bakker et al., 2012) confirmed that even in the harsh organizational conditions of a prison, personality influences the type of work behaviors and is the antecedent of job crafting behaviors. In relation to work engagement, extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness were found to be key determinants of greater work engagement in deep activities. This explanation accentuates the assertiveness, responsibility and trustworthiness of these individuals and their greater focus on their professional duties than on emotion regulation. This tendency can be explained by the rather individualistic and reserved nature of the work of the Polish prison officer population, based on formal rules (Mróz & Kaleta, 2016). Officers are less effusive in professional interactions and less likely to express positive emotions because they experience positive affect less often, and they value tasks more than relationships and sharing feelings at work. Employees who are more engaged have more to lose than those who are less invested in their own work. They invest energy, time, and want to accomplish more, so they are more committed to mobilizing additional resources not to lose what they have already accomplished, so they are not eager to be effusive in relationships, but rather task-focused, which would confirm the results. Studies that have confirmed the relationship between vigor and openness to experience (represented by intellect in this study) may indicate an increased willingness to engage in work tasks while focusing on seeking new experiences and treating work responsibilities as an opportunity for growth (Mróz & Kaleta, 2016). Therefore, emotional stability, shown in the study to be important for vigor, appears to be beneficial to work effort because it allows for greater flexibility and approachability in responding to the needs of supervisors and inmates. Agreeableness, on the other hand, was found to be protective for negative expressions of lack of work engagement, while it is not significant for positive work engagement (Tims et al., 2015). Extraversion, agreeableness, and intellect have been shown to be key to occupational well-being, especially in terms of building positive relationships. It has been confirmed that if employees perceive the work environment as positive, though challenging, they readily draw on individual resources such as well-being (Shuck & Reio, 2014). Intellect influenced the variable contribution to the organization, while extraversion and agreeableness influenced fit with job demands and mentally and physically demanding aspects of work. Other empirical studies indicate a direct, sustained and chronic influence of neuroticism and extraversion as innate predispositions to experience happiness, to a lesser extent an indirect and reactive, i.e., reinforcing influence of situational factors only (Porczyńska-Ciszewska & Kraczla, 2017). Our study confirmed the effects of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness on well-being and the weak relationship of intellect with organizational contribution. This is consistent with the model of Costa and McCrae, who argue that there are associations of enduring personality traits (extraversion, neuroticism) with well-being, causing a tendency to perceive and evaluate events in such a way that reality appears better. The analyses showed a significant indirect effect of subjective well-being for the relationship between penitentiary unit type, active coping, as well as avoidant behaviors and work engagement in the Polish group. Closed prison officers more often reported higher subjective well-being. Work engagement is a complex psychological phenomenon (Piotrowski et al., 2020b). In our study, these traits were not found to be significant, indicating that the work situation in a prison-type organization is different. Instead, agreeableness and conscientiousness were found to be related to the relational components of the well-being model, which are related to the desire for certain events with positive or negative coloring. Well-being is constructed by events that enhance the sense of satisfaction, satisfying relationships with others, and tasks well performed and opportunities for growth (Porczyńska-Ciszewska & Kraczla, 2017). Autonomy, pressure, organizational structure, opportunity for self-expression, and co-worker trust subjectively interpreted by employees resulted in employees making decisions about how hard they would work, how satisfied they would be, and how engaged they would be with the organization based on their interpretation of the workplace atmosphere. Autonomous participation in decision-making improves POs’ work and takes care of their well-being and the ability to influence their own career path and professional development. An increase in employee engagement and well-being is unlikely to occur with a negative overall perception of the organization, shown by other research, where experiencing a positive work environment has been shown to broaden task-related thought processes and have strong implications for engagement (Shuck & Reio, 2014). If employees experience and interpret their work positively (Brown & Leigh, 1996), then they believe that their engagement and personal contributions matters. Furthermore, if they feel that the organization is supportive of their work and well-being, they increase their job tasks and have a greater willingness to seek additional resources and modify the cognitive boundaries of their work. This job crafting behavior provides inspiration to become more engaged, to devote more energy and attention to work, and to make changes in the way they work to meet the demands of the dynamic prison work environment. When employees experience autonomy in creating their own work environment, their propensity to modify existing work behavior also increases, and with them, engagement increases. This study was based on self-reports and was carried out in a single organization, which limits the interpretation and generalization of the results. The study was limited by being reduced to a single measurement, which in the future can be diversified, e.g. with reports of systematic psychoeducational job crafting training as a strategy for building engagement. It may result in better well-being (de Devotto & Wechsler, 2019), because analysis of Polish POs showed that they possess the personal and professional competencies for effective performance of professional tasks (Gordon, 2014), and at the same time, they do not fully use the potential they possess. Therefore the results of such training of this difficult dispositional group may in the future provide interesting material for gender, corps, years of work determinants of POs’ behavior at work in prisons or for mediation-moderation analyses of the job crafting effect, in relation to the components of engagement, well-being, job satisfaction, sense of work, achievement motivation, and coping stress for a comprehensive demonstration of the relationship of the components of positive psychology.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study showed how personality traits affect the behavior of prison officers in the workplace. Prison officers with high agreeableness and conscientiousness were found also high on work engagement, job crafting, and well-being. Extraversion, conscientiousness and intellect determined the type of job crafting strategies. Extraversion and conscientiousness were important for building work engagement and well-being at work. The influence of intellect was also found to be significant.

Personality generates a certain and individual model of prison officers’ behavior, and in particular agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion and intellect influence the performance of daily tasks. Job crafting, work engagement and well-being are also a certain set of work behavior.

In the case of job crafting, the analysis showed that more agreeable, conscientious, and extroverted officers are more likely to use proactive job crafting strategies of seeking resources in relationships with colleagues, in the organization, or in creating new challenges and reorganizing tasks, thus making their work more meaningful and engaging.

Extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness were found to be key determinants of work engagement in deep activities. This explanation accentuates the assertiveness, responsibility and trustworthiness of these individuals and their focus on professional duties rather than on emotion regulation.

Job crafting behavior provides inspiration to become more engaged, to devote more energy and attention to work, and to make changes in the way they work to meet the demands of the dynamic prison work environment. This finding is consistent with current scientific reports on this subject.

There is a need to further develop knowledge of POs’ work, considering the differences and similarities of the penitentiary systems of the countries in which they serve.