BACKGROUND

Descriptive models of personality disorders (PDs) have undergone significant transformation in contemporary times, shifting from categorical models dominated by personality types to dimensional ones, focusing on the level of severity and pathological traits. Traditional categorical models lack empirical support and have limited clinical utility (e.g., Bornstein & Natoli, 2019). There is insufficient evidence for distinct types of disorders through factor analysis, while empirical evidence supports continuity between traits of healthy and pathological personality (Hopwood et al., 2019). Clinicians diagnosing personality types have struggled with nonbinary distributions, excessive comorbidity, and diagnostic heterogeneity, resorting to Not Otherwise Specified categories, which is far from optimal (Bach et al., 2022). While DSM-5 Section II is still an official model for diagnosing PDs within categorical models, both DSM-5 Section III Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2022) propose a reconceptualization of PDs based on common, core features.

In the DSM-5 AMPD and ICD-11 models, the core definition of PDs is refined to encompass impaired functioning in the self and interpersonal domains. In the AMPD, the self domain involves distortions of identity and self-direction, while the interpersonal domain involves distortions in the ability to engage in intimacy, and being empathic (for ICD-11 details see WHO, 2022; Blüml & Doering, 2021). Recognizing the level of personality functioning1 as a condition for PD diagnosis stems, among other reasons, from its strong relationship with psychosocial functioning, allowing for more accurate predictions of clinically significant phenomena. These include psychosocial functioning (Buer Christensen et al., 2020), prognosis regarding treatment effects and dropout rates (Busmann et al., 2019), as well as the risk of harm to self or others (Mulder, 2021), dissociation, or poorer reflective functioning (Bach & Simonsen, 2021). Furthermore, both classifications also allow a fine-grained, individualized personality profile to be provided by incorporating pathological maladaptive personality traits, which are closely aligned with the Big Five model (Chmielewski & Morgan, 2013; Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 2008; see also: Oltmanns, 2021). Personality traits are more closely tied to innate functioning and represent stable individual differences, and are good at capturing specific forms of PDs (i.e., their manifestations, their “flavour”; Sharp & Wall, 2021).

User-friendly methods that are brief, accessible, and concise are essential for screening, large-scale PD research, and clinical assessment. The importance of research based on dimensional models of personality psychopathology is recognized globally and in Poland (Łakuta et al., 2023a, 2023b). There is a continuing need to verify the relevance of these models, especially Criterion A assessment methods, across different countries and cultures (Dereboy et al., 2018).

The Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale (SIFS; Gamache et al., 2019) was developed to assess Criterion A following the AMPD’s publication. It reflects the AMPD DSM-5 conceptualization of personality pathology, covering four elements – Identity, Self-direction, Empathy, Intimacy – and an overall pathology factor. The SIFS can identify general impairments in self and interpersonal domains. It is brief (24 items), has good content validity (Waugh et al., 2021), aligns well with the meta-structure of personality impairment (Sleep et al., 2024), and provides valid estimates for the four Criterion A elements (Gamache et al., 2019). Though based on the AMPD framework, it has also been effective in distinguishing severity levels in the ICD-11 PD model (Gamache et al., 2021a).

Since its introduction, the SIFS has been used in multiple settings (e.g., clinical, community) and with multiple populations (e.g., patients with PD, private practice patients, police officers, pregnant women during the COVID pandemic; e.g., Angehrn et al., 2023; Gamache et al., 2022a, b). It has also been used to study numerous functional, diagnostic, and interpersonal impacts and outcomes (e.g., stalking and physical aggression perpetration, discrimination of severity profiles in patients with borderline pathology; Gamache et al., 2021b, 2023; Leclerc et al., 2022). It is only recently, however, that results for translations and cultural adaptations of the SIFS – which was originally developed in French – were published. Macina et al. (2023) reported, for the German translation of the SIFS, large test-retest reliability and strong correlations with validated personality impairment self-report questionnaires and interviews, but failed to obtain adequate model fits in factor analysis, in contrast with those reported for the original instrument. Samylkin et al. (2023) found that the Russian adaptation of the SIFS demonstrated good criterion and discriminant validity. It effectively differentiated individuals with PD from healthy participants and those with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and showed good sensitivity in assessing the severity of personality pathology.

CURRENT STUDY

The present study was aimed at investigating the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale (SIFS-PL). Our objective encompassed the assessment of the questionnaire’s construct validity (factor structure), reliability, and validity. We anticipated that the SIFS-PL would show similar reliability to the original version and conform to a second-order structure with four elements and an overarching personality impairment factor. We expected that criterion validity, measured by the PID-5, would align with other studies on personality pathology levels, showing high correlations between maladaptive traits and the overall SIFS score, as well as specific domains (e.g., Identity with Negative Affectivity, Self-direction with Disinhibition, Empathy with Antagonism, and Intimacy with Detachment). We also anticipated significant differences between participants with psychological difficulties (PD group and those with depression) and non-clinical community samples, with the SIFS effectively distinguishing between these groups.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study involved 394 adult volunteers from six different samples (detailed information is presented in Supplementary materials). Across all samples, women predominated (83.2%), with an average age of 30.9 years (SD = 9.6).

MEASUREMENT

The Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale Polish Adaptation (SIFS-PL). The Polish adaptation of the Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale (SIFS; Gamache et al., 2019) was used to assess the severity of PDs (Identity, Self-direction, Empathy, and Intimacy). Participants complete a 24-item self-description rated from 0 (does not describe me at all) to 4 (describes me completely accurately). The scale was initially translated, followed by an independent back-translation process, after which feedback was provided by the first author of the original version.

Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5). The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5; Polish adaptation: Rowiński et al., 2019a, 2019b) was used in the clinical PD sample only (sample 6) to assess maladaptive personality traits. The PID-5 is a self-report assessment of 25 facets of personality pathology organized into five domains (Negative Affectivity, Detachment, Antagonism, Disinhibition, and Psychoticism). It consists of 220 items rated on a four-point Likert-style scale from 0 (very false or often false) to 3 (very true or often true) and was adapted and validated in Polish samples by Rowiński and colleagues (2019b). The PID-5 domains are compatible with the trait domain qualifiers included in the ICD-11 framework (Bach et al., 2017).

DATA ANALYSIS

Reliability of the SIFS was tested by Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω (Deng & Chan, 2017).

Construct validity was tested by factor analysis and especially comparing several factor models. We replicated the procedure reported by the authors from the original scale (Gamache et al., 2019) across the entire sample. Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with weighted least squares with an adjusted mean and variance estimator, we calculated data fit indices for five different plausible models, each based on different justified assumptions about the structure of personality impairment: Model 1 – a basic one-factor model, grounded in an approach suggesting the unity of the dimension of PD depth; Model 2 – a two-factor correlated solution with self and interpersonal functioning as factors; Model 3 – a four-factor correlated solution aligning with the theoretical elements of Identity, Self-direction, Empathy, and Intimacy; Model 4 – a second-order orthogonal solution with the four factors loading onto a general personality pathology factor. Such a model aligns closely with the Criterion A AMPD conceptualization, where the four Level of Personality Functioning (LPF) dimensions are indicators of an overarching global dimension of personality pathology; it was also the model retained by Gamache et al. (2019); Model 5 – an exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) bifactor, with all items loading both on the four dimensions and on an overarching general personality pathology factor. We evaluated the global fit of the third-order CFA models using the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Because of the large sample, we did not rely on the χ2 test. We considered CFI values > .90 and RMSEA values < .08 as an acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004). We conducted all factor analyses in Mplus 8.

Criterion validity was tested by (1) correlations of the SIFS with PID-5 in sample 6 and (2) analysis of variance of SIFS across samples 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 (sample 3 was excluded as it closely resembled sample 1).

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND RELIABILITY

Descriptive statistics and reliability results are presented across three levels of analysis: SIFS total score, domain functioning (self and interpersonal impairments), and the four elements (Identity, Self-direction, Empathy, Intimacy). After collapsing all six subsamples, the mean score for the SIFS total was 1.66 (SD = 0.78), while SIFS Interpersonal and Self scores were respectively 1.34 (SD = 0.81) and 1.97 (SD = 0.87; see Supplementary materials Table S2 for details). Regarding reliability at the most specific level of analysis, Cronbach’s α ranges from .68 (questionable value) for the Self-direction subscale to .84 (good value) for Identity, indicating an overall sufficient reliability. Results were good at the dimensional level (α Self = .87 and α Interpersonal = .85), and were excellent (α = .91) for the total scale.

CONSTRUCT VALIDITY

The evaluation of fit indices (Table 1) revealed that the basic one-factor model (Model 1) exhibited unsatisfactory fit to the data. However, the two-factor (Model 2) and four-factor (Model 3) models, as well as the second-order CFA model (Model 4), demonstrated a good fit based on CFI but showed a small misfit in terms of the RMSEA index. The bifactor solution incorporating the four element subscales and one general bifactor (Model 5) exhibited both CFI and RMSEA fully satisfactorily. However, the four scales were not clearly loaded by the intended items because some of the items loaded only the general bifactor. Of note, in the CFA models of this study, no correlations between error terms had to be implemented to enhance model quality, yet the achieved fit is comparable to that obtained by Gamache et al. (2019).

Table 1

Goodness-of-fit statistics for the models estimated on the Polish adaptation of the Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale

[i] Note. CFA – confirmatory factor analysis; CFI – comparative fit index; TLI – Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation; CI – confidence interval. See Supplementary materials for detailed loadings for each model (Tables S3-S7).

CRITERION VALIDITY

Correlations with pathological trait dimensions. We hypothesized that the criterion validity with the PID-5 would mirror findings from other studies investigating the level of personality pathology (severity of PDs), where both Criterion A and Criterion B assessments would exhibit a positive and at least moderate correlation (e.g., Hentschel & Pukrop, 2014; Morey et al., 2022). The hypotheses regarding correlations in the PD group (N = 50) were consistent with expectations (see Table 2). Firstly, all maladaptive domains displayed significant and high correlations with SIFS total (ranging from .43 for Disinhibition to .76 for Detachment), indicating that higher levels of maladaptive traits were associated with more impaired personality functioning. Positive correlations were found with the Interpersonal and Self components, with some figures suggestive of discriminant validity (e.g., Antagonism was correlated with interpersonal functioning at .60 but with the self domain at .30). Secondly, SIFS Identity was strongly linked to internalizing aspects of pathological traits, specifically Negative Affectivity (.67) and Detachment (.75). SIFS Self-direction exhibited a substantial correlation with Disinhibition (.53), SIFS Empathy displayed a notable correlation with Antagonism (.58), while SIFS Intimacy correlated with Detachment (.68). It is relevant to analyse detailed personality facet scores and their associations with the SIFS across various levels (overall score, domains, and four elements). At the facet level, all but Submissiveness evinced significant correlations with at least one SIFS score. Some facets had limited significant correlations (e.g., Attention Seeking demonstrated a significant positive correlation only with Empathy impairment). Conversely, some facets evinced moderate to strong correlations with all SIFS scores (e.g., Perseveration, Withdrawal).

Table 2

Correlations between SIFS dimensions and traits measured with the PID-5 in sample 6 (N = 50)

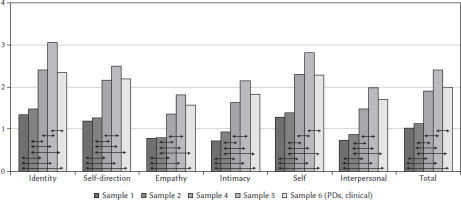

SYSTEMATIC DIFFERENCES IN SIFS-PL SCORES ACROSS SAMPLES

Analysis of variance (Welch’s F) results revealed significant differences among the examined samples 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 (see Table 3). The highest scores across all SIFS subscales were observed in sample 5, which included individuals with a severe episode of depression. The clinical group (PD sample 6) and the group with moderate depression (sample 4) had similar scores, while the non-clinical samples (1 and 2) had the lowest scores across all SIFS levels. Statistically significant differences based on post hoc tests (Games-Howell) are presented in Figure 1. Overall, they indicate that samples 1 and 2 on the one hand, as well as samples 4 and 6 on the other hand, do not significantly differ from each other in any of the subscales. Differences emerge between the clinical and depressive samples in the Identity component, influencing the self domain and subsequently the overall SIFS score. Additionally, each of the non-clinical samples (1 and 2) significantly differed from all other samples across all SIFS dimensions. In sum, each of the four SIFS subscales, the two domains score, and the overall SIFS score all have the potential to differentiate significantly between the examined samples, which is evident especially for samples 4, 5 and 6 vs. other samples.

Table 3

Comparison of samples in regard to differences in total score and SIFS subscales. Descriptive statistics and the result of Welch’s test

DISCUSSION

Firstly, as anticipated, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was excellent for the overall SIFS score and acceptable to good for the four subscales and two domains (self and interpersonal).

Secondly, regarding the hypothesis favouring a four-factor higher order structure, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis allow this hypothesis to be confirmed based on the CFI. The four-factor CFA model (Model 3) represents the theoretical model best aligned with Gamache and colleagues’ (2019) work. One item (item 6) had a problematic loading; Gamache et al. (2019) also reported some underwhelming psychometrics for that specific item, calling into question its inclusion in future works on the SIFS. (See more detailed discussion 1 in the Supplementary materials).

Thirdly, consistent with our hypothesis, the criterion validity of the SIFS as a measure of the level of personality functioning in relation to the PID-5 within a clinical group yielded results similar to those from other studies. All maladaptive traits and the majority of trait facets exhibited significant and strong correlations with both the SIFS total score and the SIFS self and interpersonal domains. In their research, Gamache and colleagues (2019) detected correlations between the SIFS total score and PID-5-SF trait domains in the high to very high range, ranging from .49 for Antagonism to .81 for Detachment. In our clinical sample, the lowest correlation for the total score was .43 for Disinhibition, whereas the highest was .76 for Detachment. The results were also consistent with hypotheses regarding expected correlations between specific SIFS subscales and particular pathological traits. We observed very similar correlation patterns to those reported by Gamache and colleagues (2019), not only for the hypotheses-specific correlations but also in general, as we found moderate to high correlations for the majority of pathological traits and their facets. Other researchers have also demonstrated a strong overlap between the SIFS and the PID-5 (Roche & Jaweed, 2023; Waugh et al., 2021), and that this issue may be somewhat more pronounced for the SIFS in contrast with other personality impairment measures. Improving the discriminant validity of the SIFS should be the focus of future works on the instrument. (See more detailed discussion 2 in the Supplementary materials).

Fourthly, in further investigating criterial validity, we have demonstrated that SIFS scores (total, domains, and elements) can distinguish between community samples, depressive samples, and PD samples. Of note, higher SIFS-PL scores were obtained for the severely depressed group (sample 5), and not for the PD one (sample 6). It is likely that depression in sample 6 co-occurred with PDs. The majority of outpatients diagnosed with depression meet the criteria for at least one type of PD (e.g., 64% – Fava et al., 2002). A strong interrelationship between depression and PDs is also observed in studies using the AMPD. For example, Vittengl and colleagues (2023) noted an empirical overlap between traits and dysfunction as part of the personality in the AMPD most relevant to depression, and they found that trait and dysfunction domains each had unique connections to depression. However, higher SIFS scores for the severely depressed group compared to the PD group may also suggests that the SIFS-PL can be a good index of general severity, but not necessarily only of PD-specific severity. This is in contrast with the claim that Criterion A should reflect PD-specific manifestations (e.g., Morey, 2017) and raises concerns regarding the discriminant validity of the SIFS-PL. However, this issue is far from specific to the SIFS. For instance, Oltmanns et al. (2018) demonstrated, using the same dataset, that a general factor of PD evinced strong correlations (range .70 to .92) with a general factor of personality and a general factor of psychopathology (p factor), suggesting poor discrimination between them.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE STUDIES

Among the limitations of this study, participant selection issues and limited participant information are notable. Data were mainly collected online, except for the clinical sample with PDs (sample 6). Depression severity was assessed via a screening questionnaire, with participants recruited from social media groups, and PD diagnoses in these samples were not examined. The gender distribution imbalance in the samples is another limitation. Since the samples are predominantly composed of women, the validation is primarily applicable to females2. Additionally, comparisons involving sample 6 (PD), which is more gender-balanced than other samples (64% female participants – Table S1, Supplementary materials), should be interpreted with caution. Gender differences in the prevalence of specific PD types are evident, but there are questions about whether these disparities reflect true prevalence or are influenced by assessment bias (e.g., Samuel et al., 2010; Skodol & Bender, 2003). For example, they may be related to tendencies in self-reporting symptoms (e.g., women with BPD are more likely to present with PTSD and eating disorders – Johnson et al., 2003). Samuel and Widiger (2009) also observed that the five-factor model (FFM) showed no sex-related effects on ratings for male and female cases, suggesting that the FFM might be less prone to gender bias. Since it is difficult to obtain a clear picture of gender differences, particularly in self-report measures of PDs, future validation studies of the SIFS should include a gender invariance analysis.

The relationship between SIFS and PID-5 was studied in a small group of 50 individuals, and while findings were consistent with expectations, replication in larger, more diverse clinical cohorts, including inpatient settings, is needed. Additionally, correlations between SIFS-PL and PID-5 might be inflated due to the shared method (self-report questionnaires), highlighting the need for multi-source and multi-method assessments to validate SIFS-PL.

CONCLUSIONS

The preliminary study on the Polish version of the Self and Interpersonal Functioning Scale has shown promising reliability and validity. Studies conducted on Polish samples yielded results similar to those presented in the original SIFS article. The SIFS-PL can be employed in scientific research grounded in dimensional models of PDs, allowing a personality dysfunction assessment (e.g., for screening purposes) in patients in mental health care. It is also worthwhile to further test the SIFS-PL as an assessment tool and to establish its clinical utility in health care settings.

Supplementary materials are available on the journal’s website.

ENDNOTES

There are many ways to name the concept of levels of personality functioning that refer to a similar concept but derive from different approaches, e.g., PD severity, personality impairment, personality pathology, and level of personality organization.

The authors thank the anonymous reviewer for their remark, which we hereby expand upon.