BACKGROUND

Religiosity is perceived as a key factor in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward social issues (Shariff et al., 2016) and plays a pivotal role in shaping prejudices (Brandt & Van Tongeren, 2017). Ambivalent sexism, a form of gender-based prejudice, encompasses both hostile and benevolent attitudes toward women. Hostile sexism entails negative, derogatory beliefs, while benevolent sexism reflects positive yet patronizing attitudes that reinforce traditional gender roles (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Though both contribute to gender prejudice, benevolent sexism is especially insidious, appearing positive yet reinforcing inequalities (Glick & Fiske, 2001). Research shows that it undermines women’s autonomy, enforces gender roles, and affects personal and professional achievements (Dardenne et al., 2007). Ambivalent sexism is also linked to negative outcomes such as reduced support for gender equality (Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2020), acceptance of rape myths (Hill & Marshall, 2018), and violence against women (Gutierrez & Leaper, 2024).

Religion must be understood within a broader social context, considering power dynamics, social structures, and historical changes (Hjelm, 2014). This critical approach suggests that religiosity’s influence on sexism is mediated by how religious institutions and teachings reflect and reinforce societal norms and inequalities. For instance, the selective interpretation of religious texts can be used to justify both benevolent and hostile sexism, thereby contributing to the complexity of gender dynamics within religious communities (Alcidi et al., 2023). Furthermore, members of religious groups display high levels of readiness to deny the group’s wrongdoing (Besta et al., 2014) and to show outgroup negativity towards members of different religions (Jaśkiewicz & Sobiecki, 2022).

Due to associations with various forms of prejudice, a growing body of research has attempted to explore the complex relationship between religiosity and ambivalent sexism, yet yielding varying results. Hence, in this study we conducted a novel systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the relationship between religiosity and ambivalent sexism, with attention to the examined groups.

Previous research has identified mechanisms linking religiosity to attitudes toward women, including traditional gender roles (Glick & Fiske, 2001), moral values (Wood & Eagly, 2002), and social norms (Glick & Fiske, 2001; Wood & Eagly, 2002). However, studies on religiosity and ambivalent sexism show inconsistent results. While some found a positive link between religiosity and both forms of ambivalent sexism (Burn & Busso, 2005), others found no significant relationship with hostile sexism (Hellmer et al., 2018), and one reported a negative relationship with hostile sexism among Jewish men (Gaunt, 2012). This inconsistency led to further investigation. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines ensured a rigorous and transparent methodology (Page et al., 2022). Integrating the results of multiple studies provides a comprehensive and evidence-based assessment of the relationship between religiosity and ambivalent sexism.

DEFINING AND MEASURING RELIGIOSITY

Allport and Ross (1967) defined religiosity as “an individual’s involvement in, commitment to, and expression of religious faith and practice” (p. 4). Similarly, Gorsuch (1988) defined religiosity as an individual’s “degree of involvement in and commitment to religious beliefs, practices, and institutions” (p. 123). These definitions highlight the importance of cognitive (i.e. the mental or intellectual dimensions of one’s religious beliefs and experiences) and behavioral (i.e. observable actions, rituals, practices, and behaviors that individuals engage in as part of their expression) components of religiosity.

Another approach to defining religiosity is rooted in the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity. Intrinsic religiosity refers to an individual’s internal, personal motivations for religious involvement, such as a search for meaning and purpose, and extrinsic religiosity refers to external motivations, such as social status and rewards (Allport & Ross, 1967).

Given the lack of a universally accepted definition of religiosity in scientific literature, inclusion criteria for religiosity measures in the meta-analysis were broad, covering a range of religious beliefs and practices. Measures included assessments of religious attendance, beliefs, and practices. One rigid criterion was set, requiring any scale measuring religiosity to have more than two levels of measurement, avoiding oversimplified distinctions between being a believer vs. a non-believer.

AMBIVALENT SEXISM, RELIGIOSITY, AND FAITH

The ambivalent sexism theory by Glick and Fiske (1996) differentiates two complementary forms of gender beliefs, differentiating into hostile and benevolent sexism. Religious commitment has been linked to endorsing both hostile and benevolent sexism across different faiths (Burn & Busso, 2005; Glick et al., 2016; Hannover et al., 2018; Mikołajczak & Pietrzak, 2014; Taşdemir & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2010). For example, traditional interpretations of the Bible in Christianity have been used to support male dominance in relationships and society (Orme et al., 2017). Similarly, some Islamic interpretations view men as protectors and maintainers of women, limiting women’s mobility and autonomy while granting men more freedom (Mir-Hosseini, 2006).

Shared scripts of Abrahamic religions, including Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, also include teachings about creating men and women as complementary but distinct beings with assigned gender roles (Leavitt et al., 2021). These teachings have been used to justify gendered roles in relationships, family, and society. However, religions may differ in their adherence to teachings. For instance, in Europe, Muslims are more retentive in their levels of religiosity (i.e. subjective importance of religion, service attendance, and praying frequency) than Christians during adolescence (Simsek et al., 2019). Consequently, considerable attention was paid to the diverse religious backgrounds from which the data were collected.

RELIGIOSITY AND GENDER

Significant gender differences in self-declared religiosity are very robust across studies (Schnabel, 2018). Women tend to be more religious than men, regardless of their religious affiliation (e.g. Beit-Hallahmi, 2003; Schnabel, 2018). However, even though women are generally more religious, they are less dogmatic – they show a weaker tendency for rigid adherence to beliefs or principles without considering alternative perspectives or evidence (Schnabel, 2018). Dogmatism’s promotion of inflexible and unquestioning adherence to beliefs likely intensifies gender-based prejudice, potentially widening the gap in sexism levels between genders (Kossowska et al., 2017). Understanding dogmatism could shed light on persistent sexism and its gender differences (Brandt & Van Tongeren, 2017). It might explain why the relationship between benevolent or hostile sexism and religiosity is often weaker among women compared to men (e.g., Davis et al., 2022; Glick et al., 2016; Hellmer et al., 2018; Paynter & Leaper, 2016), as dogmatism upholds traditional gender roles, promotes literal scriptural interpretations reinforcing male dominance, excludes women from leadership positions, controls women’s autonomy, and fosters discrimination against non-conformists, and thus women are less prone to endorse it (Wood, 2019).

METHODS

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

The following eligibility criteria were used to select studies for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis:

The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The study was published in the 21st century (from 2001 to 2023).

The study used a quantitative research design.

The study was conducted on adult participants.

The study used a measure of religiosity that was deemed acceptable for inclusion in the meta-analysis (see the section on Defining and measuring religiosity).

The study investigated the relationship between religiosity and at least one form of ambivalent sexism (hostile or benevolent).

The study provided sufficient statistical information for the effect size to be calculated (i.e. sample size and Person’s r values from zero-order correlation).

Any studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded from the review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

SEARCH AND SELECTION PROCESS

EBSCOhost was employed to search PsycINFO, SocINDEX, and MEDLINE databases for articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 2001 and 2023. The search string “religiosity” AND (“ambivalent sexism” OR “benevolent sexism” OR “hostile sexism”) was selected, as it aligned precisely with the study’s objectives, based on a nomenclature analysis of the literature.

The study selection process was conducted in two stages: title/abstract screening and full-text screening. Two reviewers independently screened retrieved articles to determine their eligibility based on pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of selected articles were also independently reviewed to ensure they met the inclusion criteria.

The extracted data included Person’s r values from zero-order correlations, sample size, population characteristics, measures of religiosity and form(s) of ambivalent sexism, and findings related to the relationship between these constructs.

STATISTICAL PROCEDURE

This systematic review and meta-analysis were registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF). The registration can be accessed at https://osf.io/6dbsp. The data and code are available at https://osf.io/4p5wz/. The studies were coded and entered into RStudio (R Core Team, 2023) using a pre-designed template (an .xlsx file) independently by two researchers and compared to check for any errors. The data were then analyzed using the RStudio package metafor (Viechtbauer, 2010).

Effect sizes for each study were calculated using Fisher’s z-transformed correlation coefficients and aggregated using a random-effects model to accommodate potential heterogeneity. Meta-analyses assessed heterogeneity using Q, I2, and τ2 statistics. A Q statistic p-value below .05 indicates significant heterogeneity. I2 values range from 0% to 100%, with higher values showing greater inconsistency among study effects. Tau-squared (τ2) estimates the variance in true effect sizes across studies, with larger τ2 values suggesting more variability and higher heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2009).

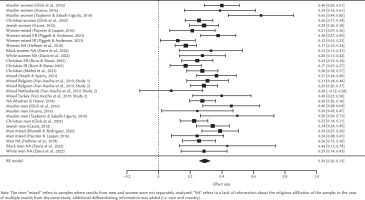

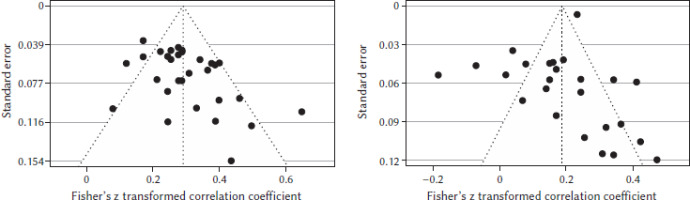

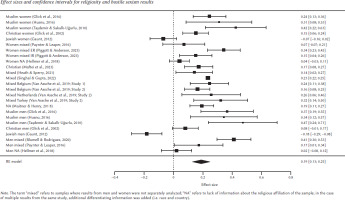

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots (Sterne et al., 2011; Figure 3). The results were presented using forest plots (Figures 2 and 4), which visually display the effect sizes and confidence intervals (CI) for each study, as well as the overall effect size estimate. The effect size estimates were also accompanied by their respective 95% CI and p-values. Procedures were conducted separately for religiosity with benevolent sexism and religiosity with hostile sexism.

RESULTS

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS

Sixteen unique articles met the eligibility criteria, and the total sample size was 8,554 (M = 285.13, SD = 190.65) for the analysis of the relationship between benevolent sexism and religiosity and 30,443 (M = 1217.32, SD = 4580.73) for the analysis of the relationship between hostile sexism and religiosity. Due to a lack of a clear rationale for selecting either an extrinsic or intrinsic religiosity measure and an intention to demonstrate their distinctiveness for this data analysis, both were included, leading to samples from two studies being analyzed twice (Burn & Busso, 2005; Piggott & Anderson, 2023). Publication years ranged from 2002 to 2023.

RESULTS OF SYNTHESES

Table 1 presents the list of studies included in the review and meta-analysis, along with the study details. In the 16 publications, 55 results of correlation between religiosity and forms of ambivalent sexism (30 for benevolent sexism) were registered. Out of 30 correlation results, benevolent sexism had a significant positive correlation 28 times. The remaining two results were not significant:

Table 1

Summary of studies on the correlation of religiosity with gender essentialism, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism

| Citation | Sample | Religiosity | Ambivalent Sexism | Pearson’s r | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blumell & Rodriguez, 2020 | 291 self-identified gay men in the UK (n = 130) and the US (n = 161) with various religious backgrounds | A 12-item revised religious scale (adapted from Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 2004; α = .92) | An 18-item sexism scale (adapted from Ambivalent Sexism Inventory; Glick & Fiske, 1996; HS: α = .94; BS: α = .87) | HS: r = .39*** BS: r = .37*** | Compared to the other results in the table, strong positive correlations with both hostile and benevolent sexism among gay men living in the UK and the US |

| Burn & Busso, 2005 | 398 Christian participants (no information about gender ratio provided) | The Intrinsic/ExtrinsicReligious Orientation Scale-Revised (8 items for intrinsic and 6 for extrinsic; Gorsuch & McPherson, 1989; ER: α = .89; IR: α = .77) | Benevolent sexism with 11 items from Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (α = .83) | IR-BS: r = .17** ER-BS: r = .24** | Extrinsic religiosity had a stronger correlation with benevolent sexism |

| Davis et al., 2022 | Participants were 282 women, of whom 99 were Black women and 183 were White women, and 228 men, of whom 45 were Black men and 183 were White men. No information was provided about participants’ religious affiliations | A single item that asked, “How important would you say religion is to your life?” | Benevolent sexism with 11 items from Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (α = .82) | For Black men: r = .41* Black women: r = .32* White men: r = .28* White women: r = .27* | The strongest positive correlation was among Black men, suggesting that gender and race may be moderators |

| Gaunt, 2012 | Participants were Israeli 826 adults (355 men and 471 women) who identified as Jewish | Indicated on a 4-point scale, labeled as follows: 1 (secular), 2 (traditional), 3 (orthodox), 4 (ultra-orthodox) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .90; BS: α = .84) | Men: HS: r = –.18*** BS: r = .33*** Women: HS: r = –.07 BS: r = .21*** | Among Jewish men religiosity was negatively correlated with hostile sexism. For both genders it was positively linked with benevolent sexism |

| Glick et al., 2002 | Participants were 1,003 randomly selected Catholic adults (508 women and 495 men) from a northwestern region of Spain | A single item that asked if a participant is (a) a nonbeliever, (b) a nonpracticing Catholic, (c) a practicing Catholic, or (d) an adherent of another religious faith | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (HS: α = .83; BS: α = .83) | Men: HS: r = .08 BS: r = .22** Women: HS: r = .15** BS: r = .25** | There were stronger positive correlations with the benevolent form of sexism among Catholics |

| Glick et al., 2016 | The final sample comprised 313 female and 122 male Muslim undergraduates in Turkey | Islamic religiosity was measured with 16 items focusing on both intrinsic and extrinsic religiosities (α = .93) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .86; BS: α = .80) | Men: HS: r = .35*** BS: r = .43*** Women: HS: r = .24*** BS: r = .38*** | There was a stronger positive correlation with the benevolent form of sexism among Muslims |

| Heath & Sperry, 2021 | 141 identified as Christian, 57 were unaffiliated, agnostic, or atheist, 11 were Jewish, 4 were Muslim, 3 were Buddhist, and 31 indicated either “other” or “prefer not to answer” | 6 items based on the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL; Koenig & Büssing, 2010) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .87; BS: α = .79) | HS: r = .14* BS: r = .35*** | There was a stronger positive correlation with the benevolent form of sexism |

| Hellmer et al., 2018 | 1207 respondents from Sweden (851 women and 356 men) but no information about their religious affiliation was given | Duke University Religion Index (DUREL; Koenig & Büssing, 2010; α = .89) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .76; BS: α = .69) | Men: HS: r = .02 BS: r = .25* Women: HS: r = .04 BS: r = .17* | Among participants from secular Sweden only benevolent sexism was positively correlated with religiosity |

| Husnu, 2016 | 157 Turkish undergraduate students (79 women and 78 men), all of whom defined their religious affiliation as Muslim | Islamic religiosity was measured using a single item rating the extent to which participants felt religious | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .74; BS: α = .76) | Men: HS: r = .33** BS: r = .24* Women: HS: r = .30** BS: r = .37** | Among Muslim women there was a stronger positive correlation with benevolent sexism, while among men – with hostile sexism |

| Maftei et al., 2023 | 418 participants (318 women and 100 men) from Romania, which is the most religious country in Europe (> 85% Orthodox Christians; Pew Research Centre, 2018) | The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-15; Huber, 2003) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (ASI: α = .77) | HS: r = .17*** BS: r = .37*** | There was a stronger positive correlation with the benevolent form of sexism among citizens of Romania |

| Maitner & Henry, 2018 | 584 Arab students (217 men and 367 women) but no information about their religious affiliation was given | “I consider myself to be religious”; “I practice my religion on a regular basis”; “I feel strongly about my religious beliefs” (α = .85) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .89; BS: α = .80) | HS: r = .19*** BS: r = .27*** | There was a stronger positive correlation with the benevolent form of sexism among Arab students |

| Paynter & Leaper, 2016 | 330 heterosexual undergraduates (188 women and 142 men) from the US with various religious affiliations | Attendance at religious services was measured using one item (a 1-7 scale) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .90; BS: α = .79) | Men: HS: r = .17* BS: r = .24** Women: HS: r = .07 BS: r = .21** | Among women the correlation with hostile sexism was not significant |

| Piggott & Anderson, 2023 | Participants were 310 mostly Christian US women | The Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale- Revised (8 items for intrinsic and 6 for extrinsic; Gorsuch & McPherson, 1989; α = .87) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (ASI: α = .75) | IR-HS: r = .15 IR-BS: r = .12 ER-HS: r = .33* ER-BS: r = .36* | Among women extrinsic religiosity had a stronger positive correlation with both forms of sexism than intrinsic religiosity |

| Singhal & Gupta, 2022 | 23,185 respondents with various religious affiliations (nationally representative samples from 49 countries) | 3 items from the World Values Survey (Haerpfer et al., 2020) | 3 items from the World Values Survey to measure hostile sexism | r = .23** | A statistically significant positive correlation with hostile sexism in the worldwide representative sample |

| Taşdemir & Sakallı- Uğurlu, 2010 | The participants were 166 (73 men and 93 women) Muslims from Turkey | 14 items to measure people’s belief in essential elements of Islam and the importance of these beliefs in their daily life (α = .83) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .84; BS: α = .81) | Men: HS: r = .44** BS: r = .46** Women: HS: r = .40** BS: r = .57** | The strongest positive correlations with both forms of sexism out of all analyzed data in this systematic review |

| Van Assche et al., 2019 (Study 1) | 227 Belgian adults (176 women) but no information was provided about the declared faith of participants | Religiosity was assessed with five statements (based on Fleischmann, 2010; α = .87) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .84; BS: α = .83) | HS: r = .24*** BS: r = .30*** | Among the mostly irreligious and mostly female Belgian sample benevolent sexism had a stronger positive correlation |

| Van Assche et al., 2019 (Study 2) | 116 Turkish adults (73 females), 99 Dutch adults (70 females), and 522 Belgian adults (398 females) but no information was provided about the declared faith of participants | Religiosity was assessed with five statements (based on Fleischmann, 2010; Turkish: α = .88; Dutch: α = .85; Belgian: α = .89) | Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items, 11 for both hostile and benevolent sexism (HS: α = .83/.89/.84; BS: α = .81/.77/.78) | T: HS: r = .31** BS: r = .38*** D: HS: r = .25* BS: r = .08 B: HS: r = .16*** BS: r = .28*** | Strongest correlations in the Turkish sample, for the Dutch sample the only statistically significant correlation was with hostile sexism |

In an analysis with a U.S. sample size of 310 women, benevolent sexism was not significantly positively correlated with intrinsic religiosity (Piggott & Anderson, 2023).

In an analysis with a Dutch sample size of 99 participants (70 women), benevolent sexism was not significantly positively correlated with religiosity (Van Assche et al., 2019).

Out of 25 correlation results hostile sexism had a significant positive correlation 18 times. The remaining six results were not significant among Jewish women from Israel (Gaunt, 2012), Catholic men from Spain (Glick et al., 2002), both women and men from Sweden (Hellmer et al., 2018), 188 U.S. women (Paynter & Leaper, 2016), and 310 U.S. women (intrinsic religiosity; Piggott & Anderson, 2023). One result was a significant negative correlation among Jewish men (Gaunt, 2012).

Twenty-four zero-order correlation results for single-faith samples were extracted. For Muslim-only samples there were six correlation results with benevolent sexism, all of them positively correlated with religiosity, and six correlation results with hostile sexism that were also positively correlated with religiosity. For Christian samples, there were five correlation results with benevolent sexism and three with hostile sexism. Only the correlation with hostile sexism among Catholic men in Spain was not significant (Glick et al., 2002). For the Jewish-only sample benevolent sexism was positive both for women (z = –.18, 95% CI [–.29; –.08]) and men (z = –.18, 95% CI [–.29; –.08]), while hostile sexism was not significantly correlated with religiosity among women and negatively correlated among men (z = –.18, 95% CI [–.29; –.08]).

There were 38 zero-order correlation results for single-gender samples. Among women, a significant positive correlation between religiosity and benevolent sexism was reported 10 times. The only exception was a study involving mostly Christian women living in the U.S., where this correlation with intrinsic religiosity was insignificant (Piggott & Anderson, 2023). Five significant positive correlations and four insignificant results regarding hostile sexism were found in female samples. Among men, all 10 correlations between religiosity and benevolent sexism were significant and positive. For hostile sexism, five were positive, two were insignificant, and there was one (previously mentioned) negative correlation.

RELIGIOSITY AND BENEVOLENT SEXISM

A meta-analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between benevolent sexism and religiosity. The analysis included 30 correlation analysis results, yielding an estimated effect size of z = .29 (SE = 0.02, p < .001). This effect size indicates a significant positive association between benevolent sexism and religiosity (Figure 2).

The 95% CI for the effect size ranged from .26 to .33. The z-value for the effect size was 16.65, indicating a highly significant relationship (p < .001). These findings provide strong evidence for the presence of a positive relationship between religiosity and benevolent sexism.

Moderate heterogeneity was observed among the studies, with an I2 statistic of 56.44%. This suggests some variability in effect sizes across the included results. The heterogeneity test revealed a significant Q statistic (Q = 67.08, p < .001), indicating that the effect sizes significantly differ among the results.

The between-study variance (τ2) was estimated to be 0.005, suggesting that a portion of the heterogeneity can be attributed to true differences between studies. The H2 statistic, representing the proportion of total variance due to heterogeneity, was 2.30, indicating a moderate contribution of heterogeneity to the overall variance.

Publication bias was assessed using the funnel plot. Out of 30 studies, five were outside the funnel shape (Figure 3), which may indicate the presence of potential publication bias or other sources of bias. However, it is important to consider other factors that could contribute to funnel plot asymmetries, such as heterogeneity or study quality.

The systematic review and results of heterogeneity and funnel plots leaned in favor of testing moderation effects in meta-analysis. However, the inclusion of moderation analysis in the meta-analysis was not feasible due to significant variation among the samples. This variation encompassed factors such as gender division, religious affiliation, and other contributing elements, such as race, measures of religiosity, and cultural backgrounds (Figure 2). Complications arose due to inconsistent reporting across studies, making it challenging to assign meaningful levels to moderators and conduct reliable analysis without risking misrepresentation of actual interactions. The presence of multiple contributing factors further added to the complexity. Given these limitations and the heterogeneous nature of the samples, it was justified to focus on a systematic review for the discussion of possible moderators, rather than attempting moderation analysis.

In summary, this meta-analysis provides robust evidence for a positive relationship between benevolent sexism and religiosity. However, it should be noted that there is moderate heterogeneity among the studies, suggesting that the effect sizes vary to some extent across different studies.

RELIGIOSITY AND HOSTILE SEXISM

A meta-analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between hostile sexism and religiosity. The analysis included 25 results, yielding an estimated effect size of z = .19 (SE = .03, p < .001). This effect size indicates a significant positive association between hostile sexism and religiosity (Figure 4).

The 95% CI for the effect size ranged from .13 to .25. The z-value for the effect size was 6.11, indicating a highly significant relationship (p < .001). These findings provide strong evidence for the presence of a positive relationship between hostile sexism and religiosity.

Substantial heterogeneity was observed among the studies, with an I2 statistic of 90.93%. This suggests considerable variability in effect sizes across the included results. The heterogeneity test revealed a significant Q statistic (Q = 192.77, p < .001), indicating that the effect sizes significantly differ among the studies.

The between-study variance (τ2) was estimated to be 0.02, suggesting that a substantial portion of the heterogeneity can be attributed to true differences between studies. The H2 statistic, representing the proportion of total variance due to heterogeneity, was 11.03, indicating a large contribution of heterogeneity to the overall variance.

Publication bias was assessed using the funnel plot. Out of 25 results, 10 were outside the funnel shape (Figure 5), which may indicate the presence of potential publication bias or other sources of bias. Again, it is important to consider other factors that could contribute to funnel plot asymmetries, such as heterogeneity or study quality.

In summary, this meta-analysis provides robust evidence for a positive relationship between hostile sexism and religiosity. Substantial heterogeneity among the studies suggests that the effect sizes vary widely across different studies.

DISCUSSION

Results of systematic review and meta-analysis confirm the positive link between religiosity and both forms of ambivalent sexism, with benevolent sexism manifesting a stronger positive link with religiosity. However, results vary significantly, which suggests the moderating roles of religious affiliation and gender in the relationship between religiosity and benevolent and hostile sexism. Most of the studies explored this link either among Muslims or Christians. The only study that focused on other religions was conducted on a Jewish sample (Gaunt, 2012), and it was the only study that indicated a significant negative correlation between religiosity and any form of ambivalent sexism (i.e. hostile) out of all analyzed studies. Also, this negative correlation was observed among men (the study also analyzed the results of women, but in this case, the correlation was insignificant).

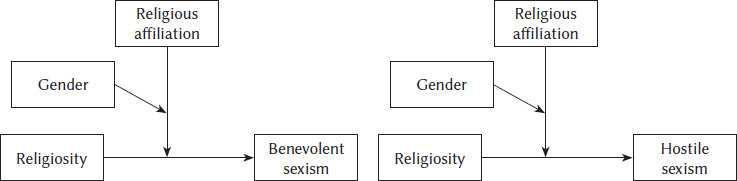

The findings suggest the need for a nuanced, intersectional approach to analyzing the links between religiosity and ambivalent sexism. These links are stronger among Muslims than among Christians or Jews, particularly for Muslim women compared to their Christian or Jewish counterparts. This indicates that religious affiliation and gender may serve as moderators, leading to the proposal of two moderated moderation models (Figure 5). The first model posits that the relationship between religiosity and benevolent sexism is moderated by religious affiliation, with this moderation further moderated by gender. The second model mirrors this structure, with hostile sexism instead of benevolent sexism.

Interesting results also came from a sample of homosexual men living in the UK and the U.S., showing that religiosity was positively correlated with both forms of sexism at similar levels (Blumell & Rodriguez, 2020). Furthermore, one study split analysis based on the race of participants and found that among Black participants, the positive link between religiosity and benevolent sexism was stronger than among White participants (Davis et al., 2022). Such results favor a more intersectional approach to studying links between religiosity and ambivalent sexism.

It is thus vital for future studies to expand their focus beyond examining the link between religiosity and sexism solely within Christian and Muslim contexts. While these two religious affiliations have been more extensively studied than other religious groups, there is a need to explore the relationship between religiosity and sexism across a broader range of religious traditions. By including diverse religious affiliations in research, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and others, a more comprehensive understanding of how different religious beliefs, practices, and cultural contexts intersect with gender attitudes can be obtained. Finally, ambivalent sexism had a stronger positive link to extrinsic than intrinsic religiosity (Burn & Busso, 2005; Piggott & Anderson, 2023).

In conclusion, conducting future studies that link religiosity with benevolent and hostile sexism, while employing an intersectional approach, is essential for advancing the understanding of the complex relationship between religion and gender attitudes. Such research can contribute to the development of more inclusive and informed strategies aimed at promoting gender equality and challenging discriminatory beliefs within religious communities.