BACKGROUND

Psychological flexibility (PF) is understood as an ability “to contact the moment as a conscious human being more fully, as it is, not as what it says it is, and based on what the situation affords, persisting or changing in behaviour in the service of chosen values” (Hayes et al., 2013, p. 188). PF is perceived as a latent construct composed of six basic dimensions, which leads to good health and living a satisfying life which is values-oriented regardless of the inner (private) experiences. The six components of PF (Hayes et al., 2016) are: (1) defusion – an ability to create nonliteral, non-evaluative contexts that diminish the unnecessary regulatory functions of cognitive events (thoughts); (2) acceptance – an ability to intentionally adopt an open, receptive, and flexible posture with respect to moment-to-moment experience; (3) self as context – an ability to see inner experiences as distinct from consciousness as such, and thus not necessarily a threat; (4) contact with the present moment – an ability to attend to what is present in a focused, voluntary, and flexible fashion, linked to one’s values and purposes; (5) awareness of one’s values as chosen, verbally constructed consequences of dynamic, evolving patterns of activity (Wilson & Dufrene, 2009); (6) committed action – an ability to develop patterns of effective action linked to chosen values.

Previous research has provided a lot of evidence in favour of the usefulness of the PF construct (Gloster et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2012; Ruiz, 2010) which was proved to mediate change processes in the therapy of most mental disorders and chronic pain (Doorley et al., 2020).

Although PF associations with different psychological variables have been tested extensively (Doorley et al., 2020), only a few studies have focused on the relationship between PF and temperament and their common role in experiencing stress, development of psychopathology or living a satisfying life. Data on the relationships between temperament, PF, and other criteria can help to improve the process of PF development. Temperamental traits describe the speed and intensity of emotional and behavioural reactions, including the speed of learning new and unlearning emotional and behavioural reactions. People with higher briskness, plasticity or mobility may be more psychologically flexible as they adapt to changing circumstances more easily. In the case of emotional sensitivity, one can expect a negative relationship with PF. From the research carried out so far we know that people differ in terms of their preferred action and cognitive styles and that these preferences are related to their temperament (Matczak, 1982; Strelau, 1974). Thus tailoring the psychological intervention processes to the temperament of individuals may positively affect the effectiveness of PF development within psychological interventions.

So far, the research on the relationship between PF and temperament has been limited to Gray’s (1991) BIS/BAS concept of temperament, some aspects of PF and psychopathological symptoms as a dependent variable. BIS is a neuropsychological system related to punishment and avoidance and is responsible for balancing the behavioural activation system (BAS). The BAS in turn is related to sensitivity to reward and approach motivation. In the research done by Pickett et al. (2011) positive associations between BIS sensitivity, experiential avoidance (EA; an aspect of psychological inflexibility) and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms were observed. The mediating effect of EA as well as mindfulness and acceptance processes was also found in the relationship between BIS and social anxiety (Panayiotou et al., 2014) and between BIS and psychological distress (Hamill et al., 2015). To the author’s knowledge, these are the only studies assessing the temperament–PF (or its aspects) relationships.

The level of perceived stress is a strong risk factor for the development of psychiatric disorders and poor health (Li & Hasson, 2020; Thoma et al., 2021). According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), the state of stress is a consequence of a person–environment interaction in which the person perceives environmental demands as exceeding their resources and coping possibilities. One of the aims of psychological interventions is to reduce the level of perceived stress in order to lead to psychopathology reduction and to higher well-being. Both PF and temperament show strong relationships with the level of perceived stress and functioning under conditions of different stimulative value. Higher PF was shown to be linked to better psychological health (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010) as well as lower stress and distress (Kent et al., 2019; Tavakoli et al., 2019; Waldeck et al., 2017). Wersebe et al. (2018) found that an increase of PF leads to a decrease in stress during the psychological intervention, whereas Gloster et al. (2017) found that PF was a moderator of the relationship between daily stress and mental health level. In the case of temperament, it is directly understood as an important moderator of the level of perceived stress, coping strategies as well as the consequences of functioning under particular stress levels (Heszen-Niejodek, 2002; Strelau, 2008). Individual temperamental traits or their combination (especially those which determine the level of emotionality – the speed and intensity of emotional reactions, i.e. neuroticism, harm avoidance, emotional reactivity, negative emotionality, behavioural inhibition, see Zawadzki & Strelau, 2009) are significantly associated with experienced stress levels, as well as with mental and somatic health.

As the relationship between PF, temperament and perceived stress has not been established directly so far, it was decided to include all these variables in one study. Given the above findings, it was hypothesised that PF will play the role of a partial mediator between temperamental traits and the level of perceived stress. The hypothesis was tested in a local community sample.

REGULATIVE THEORY OF TEMPERAMENT

It was decided to operationalise temperament according to the regulative theory of temperament (RTT). The RTT defines temperament as basic and relatively stable personality traits that specify one’s possibilities of stimulation processing (Strelau, 2008) and postulates that temperament manifests itself in the formal characteristics of behaviour which may be described in terms of temporal and energetic traits, different among people and relatively stable for the same person. These traits are present from early infancy, common for people and animals, and are biologically determined, but still are subject to change during ontogenesis. According to the RTT, temperament plays a crucial role in regulating the relationship between the human and the environment as it determines one’s possibilities of external stimulation processing and preferred ways of stimulus regulation, which is of great importance in stressful situations.

The RTT distinguishes seven temperamental traits (Cyniak-Cieciura et al., 2018): briskness (BR; a tendency to react quickly and maintain a high tempo of performed activities), perseveration (PE; a tendency to continue and/or repeat behaviour after cessation of stimuli which evoked this behaviour), rhythmicity (RT; regularity of time intervals between homogeneous reactions, which manifests in eating and sleeping habits as well as a driven lifestyle), activity (AC; a tendency to undertake highly stimulative behaviours or to supply external stimulation through one’s behaviour), emotional reactivity (ER; a tendency to react intensely to emotion-generating stimuli), endurance (EN; an ability to maintain adequate reactions in situations demanding long-lasting and highly stimulative activity), and sensory sensitivity (SS; an ability to react to sensory stimuli of low stimulative value and to detect minor differences between sensory stimuli values).

It was decided to follow the RTT approach for numerous reasons. Firstly, the tradition of research based on this theory is long and temperamental traits or their combinations were found to be risk factors for the development of various mental disorders and somatic illnesses, especially of somatic symptoms (Fruehstorfer et al., 2012), burn-out syndrome (Korczyńska, 2001), depression (Pragłowska, 2011), autism (Pisula et al., 2015), posttraumatic stress disorder (Rzeszutek et al., 2015; Zawadzki & Popiel, 2012), personality disorders (Zawadzki et al., 2012) and alcohol abuse (Miklewska & Miklewska, 2000). Secondly, the RTT distinguishes many traits, among which emotional reactivity was proved to be consistently strongly related to both symptoms of psychopathology and somatic symptoms (Strelau, 2008), and briskness to the effectiveness of psychotherapy (Popiel & Zawadzki, 2013). Finally, the research based on RTT has already delivered useful information about the temperament moderating role in preferred action style, cognitive style and in people’s functioning under different conditions.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 254 people – 133 women (52%) and 121 men (48%) aged 18-93 (M = 44.54, SD = 16.79) from the local communities – were recruited to the study. Most of them (n = 97, 38.2%) had a secondary educational level, 67 people (26.4%) had a higher educational level, 73 (28.7%) had vocational education, and 15 (5.9%) had primary education.

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted between 6th June and 5th July 2020. Participants were recruited directly by as many as 13 pollsters who followed the designated criteria for the gender, age, and education. Each pollster contacted about 20 people from their immediate and more distant social circles (friends of friends). The only exclusion criterion was being less than 18 years old. The pollsters left the paper versions of questionnaires to the participants and received them back at the agreed date (usually within a few days). Each participant was paid remuneration in the amount of PLN 50 for participation in the study. All the participants signed an informed consent form. The whole procedure was accepted by the local institutional review board.

Obtained data were analysed by calculating Pearson’s r bivariate correlations as well as by conducting linear regression and path analyses. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 23 and AMOS v. 23. The power of the analysis was checked using G*Power.

MEASURES

The Formal Characteristics of Behavior-Temperament Inventory – revised version (FCB-TI(R); Cyniak-Cieciura et al., 2018) was used to measure temperamental traits, i.e. briskness (BR), perseveration (PE), rhythmicity (RT), activity (AC), emotional reactivity (ER), endurance (EN), and sensory sensitivity (SS), with a 4-point Likert response scale (1 – definitely do not agree, 2 – do not agree, 3 – agree, 4 – definitely agree), and 15 items per scale (apart from rhythmicity – 10 items). Cronbach’s α in this study was .85 for BR, .74 for PE, .85 for RT, .86 for AC, .87 for ER, .86 for EN and .77 for SS.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire. Psychological flexibility (PF) was measured by the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011) in the Polish adaptation by Kleszcz et al. (2018). This one-dimensional tool includes 7 items and a 7-point Likert-like scale (1 – never true, 2 – very seldom true, 3 – seldom true, 4 – sometimes true, 5 – frequently true, 6 – almost always true, 7 – always true). Cronbach’s α was .89. Its cross-cultural psychometric equivalence to the original version was established and proved satisfactory (see Kleszcz et al., 2018).

Perception of Stress Questionnaire. The level of perceived stress was assessed with the original Polish tool – the Perception of Stress Questionnaire (KPS; Plopa & Makarowski, 2010). It includes 27 items assessed on a 5-point scale (1 – true, 2 – mostly true, 3 – hard to say, 4 – mostly untrue, 5 – untrue) and measures three content scales (Emotional Tension, External Stress and Intrapsychic Stress) and a Lie scale, as well as a general indicator of perceived stress, calculated as a sum of points in all three content scales. The latter was included; Cronbach’s α was .92.

RESULTS

HANDLING THE MISSING DATA

Based on Mazza et al. (2015) recommendation, the scales’ results were calculated based on the subjects who responded to all of the items. Then the number of missing cases was calculated and Little’s MCAR test was done. The percentage of missing cases did not exceed 5% with the exception of the perceived stress scale (12.6%, n = 32) and PE (5.1%, n = 13) and the number of extreme cases was small (maximum of 4 extremely low results of the PE scale). Little’s MCAR test result indicated that missing data were completely at random (χ2 = 180.08, df = 195, p = .771). Based on the recommendations of Tsikriktsis (2005) it was decided to use a pairwise deletion technique in all the analyses presented below.

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND POWER ANALYSIS

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The values for skewness and kurtosis were between –1 and +1 for all the variables. The post-hoc power analyses revealed that all the analyses had strong power > .95 (with a medium effect size of .15 and α error probability of .05).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between measured variables

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TEMPERAMENTAL TRAITS, PERCEIVED STRESS, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL FLEXIBILITY

Pearson’s r bivariate correlation analyses revealed significant relationships between PF and perceived stress (moderate and negative), PF and ER, PE (both moderate and negative), BR and EN (both weak and positive), stress and ER, PE (both moderate and positive), EN (moderate and negative) as well as BR (weak and negative). The results are presented in Table 1.

Linear regression analyses revealed that among temperamental traits only ER and PE were significant predictors of PF (F(7, 224) = 9.42, p < .001), explaining 22.7% of variance. ER, PE and AC were significant predictors of the level of perceived stress (F(7, 203) = 16.22, p < .001), explaining 35.9% of variance. Among temperamental traits ER was the strongest predictor of both PF and perceived stress (with β = .40 and β = .34 respectively). In order to test whether PF is a significant predictor of stress beyond and above temperamental traits and whether it can be assumed as a significant mediator between temperament and perceived stress, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with temperamental traits included in the first step and additionally the PF included also in the second step. Adding PF to the model increased the level of explained variance to 46.2% (ΔR = 10.4%) and the model was statistically significant (F(8, 202) = 21.71, p < .001). Standardized coefficient values of ER and PE were lowered after the inclusion of PF (β = .34 vs. β = .20 for ER and β = .23 vs. β = .16 for PE, with β = –.13 vs. β = –.15 for AC being almost the same). The results of regression analyses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Results of the hierarchical regression analyses: temperament as predictors of PF and stress as well as temperament and PF as predictors of perceived stress level

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TEMPERAMENTAL TRAITS AND STRESS – THE MEDIATING ROLE OF PSYCHOLOGICAL FLEXIBILITY

The results suggested partial mediation between perceived stress and ER and PE through PF. In order to directly test it, path analysis with the maximum likelihood estimation method (ML) was performed. Three temperamental traits – significant predictors of stress (AC, ER and PE) – were included. The model fit was ascertained using the reference values for the main fit indices (Hooper et al., 2008): the chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistic (p >. 05), the comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.95), and the root-mean-square of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08).

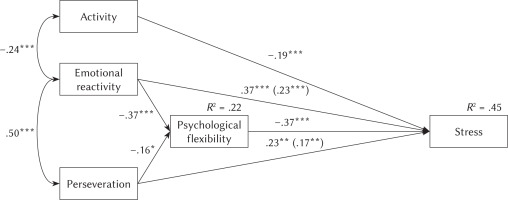

The results of path analysis revealed that the relationships between temperamental traits and perceived stress are complex, with AC predicting the level of perceived stress directly and with ER and PE being partially mediated by PF. The model proved to fit the data well (χ2(2) = 2.53, p = .282, CFI = .998, RMSEA = .032, 90% CI [.000, .133]) and explained 22% of the variance of PF and 45% of the variance of perceived stress. Standardized path coefficients as well as direct and total effects are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Relationships between temperamental traits: activity, emotional reactivity and perseveration, psychological flexibility and the level of perceived stress (χ2(2) = 2.53, p = .282, CFI = .998, RMSEA = .032, 90% CI [.000, .133])

Note. Standardized path coefficients are presented. In the case of emotional reactivity and perseveration the total effects are presented outside the parentheses and the direct effects are presented inside the parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the relationships between PF, temperamental traits, and perceived stress and to test whether PF mediates the relationship between temperamental traits and perceived stress. The obtained results generally support the hypothesis.

Regarding the relationships between PF and temperament, higher PF was associated with lower emotional sensitiveness and perseveration, higher physical endurance and speed of action. Thus PF was found to be related to two traits determining the capability of stimulation processing (ER and EN) and two traits loading the higher-order mobility factor (PE and BR). Given the theoretical definitions of temperament dimensions, the first two traits seem responsible for the aspect of being more or less sensitive to emotion-generating stimuli, and the latter two traits seem responsible for the aspect of flexibility. Two of these traits, those associated with the emotionality and the duration of emotional and behavioural reactions (namely ER and PE), were significant predictors of PF. Thus PF is related to the intensity and duration of emotional and physiological states caused by external stimulation. The results referring to temperamental traits and PF are consistent with those obtained previously by Hamill et al. (2015), Panayiotou et al. (2014) and Pickett et al. (2011), although the measured constructs are differently operationalized.

PF was not linked to AC, which is probably because activity understood from a temperamental perspective relates to the need of stimulation, whereas action included in the conceptualization of PF is a general values-oriented activity regardless of its stimulation value. Biological rhythms reflected in temperamental traits as well as sensitivity to sensory stimuli were not found to be related to PF.

In the case of the relationships with perceived stress, higher reactivity to emotion-generating stimuli and perseveration as well as lower physical endurance, activity and speed of action were associated with higher levels of perceived stress. Thus higher stimulation processing capability and lower mobility were related to being more prone to stress, which is consistent with the results obtained previously (Cyniak-Cieciura & Zawadzki, 2019; Strelau & Zawadzki, 2005; Waszkowska, 2009; see also Strelau, 1996, 2008 for a summary). From all temperamental traits as many as three were found be significant predictors of perceived stress: AC, ER and PE.

Finally, people of higher PF, and therefore those who are less stuck in unhelpful thinking processes (e.g. ruminations) with less avoidance of unpleasant thoughts, emotions and values-oriented activities, develop lower levels of perceived stress. This is consistent with findings obtained by Kent et al. (2019), Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam (2020) as well as Tavakoli et al. (2019). PF proved to be a significant predictor of perceived stress above and beyond temperamental traits.

It was found that PF serves as a partial mediator of the relationship between ER and PE with perceived stress, whereas AC is related to perceived stress independently from PF. Taking into account the strong biological background of temperamental traits (Trofimova & Robbins, 2016) it may be assumed that aspects of stimulation processing capability (ER) and of mobility (PE) lead to the development of PF, which together with temperamental traits (and possibly also with other factors) impacts the way people feel their everyday stress. However, temperament may lead to the development of PF not only through biological factors, such as the genetic background, making individuals more or less able to adapt to different circumstances and deal with internal reactions such as thoughts, emotions and physiological symptoms. It may also influence the PF through the process of education (as temperament is related to intelligence and educational achievements), modelling by significant people (as the educational process may be more or less adjusted to one’s temperamental needs) and accumulation of life experience (as temperament impacts the choice of activities, and occupation).

Reciprocal effects may also be considered. People with a lower level of ER and PE feel emotions to a lesser extent, are less moved by stressful situations, feel emotions and their physiological symptoms briefly, and engage in more stimulating activities. As probably their experiences are richer, both their temperament and PF may be reinforced. There is strong evidence that PF is subject to change under specific psychological interventions. Temperament in turn, even though it is characterised by quite a strong stability over the life-span, is also subject to some change under long-lasting experiences even of less stimulating value (Eliasz, 1981) or under short-term but intensive experiences (e.g. trauma, see Zawadzki & Popiel, 2012).

People with higher levels of ER and PE may have difficulty with developing PF, which (possibly alongside other factors) makes them more prone to stress. What we know from the previous findings is that the level of PF acquired within specified psychological interventions is higher among people with a higher baseline level of PF (Hooper & Larsson, 2015), which is not a very optimistic fact for those with lower PF and a combination of less friendly temperamental traits. On the other hand, data from temperamental research suggest that even people who are more reactive and have lower capability of stimulation processing still may function at an optimal level if only the stimulation level is within the optimal range for them and they are allowed to follow their preferences in terms of action style (Strelau, 1974). Further research may then focus on determining whether tailoring the psychological interventions and/or the external environment more to temperamentally determined preferences of people will result in higher development of PF and thus lower levels of perceived stress (or other criteria).

PF is a significant factor contributing to the feeling of stress even if other factors of a more biological background are included. The results suggest that PF has a possible temperamental background, especially in traits which are related to the strength with which the emotions are felt and to how long they are processed. This is worth testing in a longitudinal study and also using more complex operationalization of PF, including direct measurement of all six PF skills. It is possible that some of the PF skills (such as acceptance, defusion or contact with the present moment, which directly relate to acceptance/avoidance of emotions, sensations or emotion-generating thoughts) have a stronger temperamental background than others (such as awareness of one’s values, which is probably a more cognitively than emotionally based process; see Hayes et al., 2016; Wilson & Dufrene, 2009).

The research including temperamental traits and PF together with perceived stress or related variables allows us to deepen our understanding of factors influencing the perception of stress, including factors with documented biological origin (and therefore more difficult to change) and those that are more easily modified as a result of an intervention. It also contributes to our understanding of who is more likely to feel stress and experience its consequences and how to prevent or counteract these consequences. Finally, it may contribute to the research on adjustment of psychological interventions to one’s characteristics and needs (a personalized approach to therapy; see Hayes & Hofmann, 2018).

The most important limitation of this study relates to the fact that it was unintentionally conducted in the COVID-19 pandemic period. As the direct influence of the pandemic challenges could not be controlled in this study, this needs to be kept in mind when considering the study results. It is possible that dealing with usual, everyday stress which affects the population in a rather stable and random manner may bring different results. On the other hand, although the study was carried out in a specifically stressful period, the range of the dependent variable was not elevated (the analysis of the distribution of the perceived stress and difference in means suggest that the group perceived a lower level of stress than the average of the normative sample: t(118) = –4.00, p < .001 for women and t(102) = –6.40, p < .001 for men). The normative sample deliberately included people exposed to objectively strong stressors (such as people with specific occupations). This may also be the case, as the study was conducted in a period when the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was cancelled in most areas of Poland, just after the first wave of the pandemics, which turned out to be relatively weak, compared to other countries at that time. Still, the generalization of the results requires replicating the study with the additional inclusion of a measure of objective stressors, including those connected to the pandemic, if this is still relevant.

It is also worth mentioning that the study was based on a specific operationalization of temperament. It is worth replicating its results using at least Cloninger’s theory (as its dimensions were related to the change in therapy and frequently used in clinical studies; see Kampman & Poutanen, 2011; Perugi et al., 2018; Purper-Ouakil et al., 2010) or Robbin’s functional ensemble temperament model (Trofimova & Robbins, 2016), as it directly relates temperament dimensions to biological mechanisms, so it may directly deliver proof of a biological background. At the same time, the results suggest that PF cannot be perceived as the only mediator between temperament and perceived stress – there is a place for other mediators, such as cognitive factors (self-efficacy beliefs) or coping strategies. Also, other significant mediators of change in psychological interventions (such as cognitive restructuring, the level of metacognitions) may be included in further research. Finally, research done on clinical samples with different dependent variables, e.g. the level of psychopathological symptoms or well-being measures, is needed. The other limitations of the study include the restriction to a population from one country (Poland), an unrepresentative sample, and cross-sectional intergroup comparisons.