BACKGROUND

Research on national identity recognizes two qualitatively different ways of identifying with the nation. That is, one could either identify in a secure and authentic manner or, conversely, in a non-secure and narcissistic way (hereafter labelled as national narcissism; Cichocka, 2016). Although both of these types of national identity are related to the self-declared attachment to the nation, national narcissism represents a belief about the unparalleled greatness of one’s nation, which is not recognized as it should by others and a view that this nation is superior to others (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Marchlewska et al., 2022). This sense of superiority is reflected in how individuals who narcissistically identify with their nation view members of other nations. That is, they are perceived as worse and hostile (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016, 2020). Narcissistically identifying with one’s nation, however, also predicts hostile attitudes towards one’s own nation. Specifically, individuals scoring high on national narcissism are more prone to conspire against their compatriots and are willing to leave their country for a personal gain (Marchlewska et al., 2020; Molenda et al., 2023). Thus, the question arises whether the declared positive attachment to the nation in national narcissism is a mask compensating for the frustration of different individual psychological needs (Cichocka, 2016), such as low self-esteem or fear of abandonment (Golec de Zavala et al., 2020; Marchlewska et al., 2024). Within the current manuscript, we investigate this issue and stipulate that national narcissism could be interpreted as a superficial self-presentation tactic having little in common with sincere attachment with one’s nation.

PICTURING NATIONAL NARCISSISM

National narcissism could be broadly defined as a grandiose image of one’s national group, associated with a simultaneous conviction that one’s nation does not receive adequate recognition and appreciation from others, and with a sense of superiority towards other nations (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009, 2016). National narcissism is positively related to national identification (including the centrality of this identity, satisfaction with group membership, and ties with other compatriots; Cameron, 2004; Marchlewska et al., 2024) as well as to more generally defined patriotism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). Given this positive relation, to conclude about the unique effects of national narcissism on other outcome variables, researchers include them both within a single model, to control for their shared variance (e.g., Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Marchlewska et al., 2024). For the reasons outlined above, national narcissism is sometimes referred to as excessive love for one’s nation (Marchlewska et al., 2020). However, this love seems to be superficial. While negative perception towards out-groups who are violating the socio-spatial order is typical for the general population (Jaśkiewicz & Sobiecki, 2021), those scoring high on national narcissism actually use their compatriots instrumentally to justify their underlying self-serving motives (Cichocka et al., 2022; Marchlewska et al., 2020). Thus, although those scoring high on national narcissism declare their attachment to the nation, ultimately, such individuals are more likely to act for themselves, not the nation.

It might be therefore asked whether national narcissism predicts acting against a nation only during the threatening situations but is constructive otherwise. To answer, it is necessary to understand how individuals scoring high on national narcissism perceive their surrounding reality. Threats could be either external (i.e., direct and objective) or internal (i.e., perceived and subjective), and individuals could differ in their propensity to detect such threats. For example, individuals scoring high on vulnerable narcissism (which is positively related to national narcissism; Golec de Zavala et al., 2016) are extremely sensitive to any interpersonal threats and interpret the situation as threatening even when it is highly ambiguous (Rogoza et al., 2022b). Existing research also supports the notion that individuals who excessively identify with their group (i.e., narcissistically identify with it) react with aggression towards others even when exposed to imaginary threatening situations (Cichocka et al., 2022; Marchlewska et al., 2019). Thus, sensitivity to threat in individuals high on national narcissism seems to be largely elevated (Cichocka & Cisłak, 2020), to the extent that they tend to indicate many false alarms (i.e., perceiving a non-threatening situation as threatening). As a result, such individuals are constantly searching for imaginary threats (which is expressed, for instance, in a positive association with beliefs in conspiracy theories; Molenda et al., 2023; cf. Marchlewska et al., 2024). Given that they perceive the world in such a highly unwelcoming and predatory manner, the benefits they might bring to their own nation are negligible, if any (Cichocka & Cisłak, 2020).

NATIONAL NARCISSISM VERSUS SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE NATION

Is wearing a t-shirt with a “death to the enemies of the motherland” inscription an indicator of one’s interest in the history of one’s nation? Historical references can be perceived as a way to connect the past and the present in-group members and provide a sense of connection with something larger than oneself (Sani et al., 2008). However, the history of any nation is rarely an endless string of positive events and people, depending on how they identify with their nation, tend to deal with this issue in various ways (Wójcik & Lewicka, 2022). Individuals who view their nation as superior to others tend to see the primary purpose of their nation’s history as enhancing the positive image of their national group, rather than viewing history as a reliable source of factual information about the past (Wójcik & Lewicka, 2022). Such an approach to history was also shown to be connected with support for policies emphasizing in-groups’ achievements, even at the cost of ignoring some important historical events (Główczewski et al., 2022). Thus, not surprisingly, national narcissism was related to the denial of historical facts that may harm the nation’s image (Klar & Bilewicz, 2017) and to idealizing past actions of one’s own nation (Bocian et al., 2021). Hence, it could be postulated that for such individuals, possessing accurate knowledge of history is considered as less important than the desire to present their own group as flawless or superior to others (Golec de Zavala et al., 2020; Marchlewska et al., 2024). Indirect findings supporting this argument can be found in another domain important for the country where national narcissists struggle to accept facts – the realm of politics. Recently, Michalski and colleagues (2023) found that national narcissism was negatively correlated with political knowledge. Thus, the self-declared interest in a topic does not necessarily need to go hand in hand with a motivation to search for facts.

ASSESSING THE ABILITY TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN ACCURACY OF KNOWLEDGE AND BIAS – THE OVERCLAIMING TASK

As mentioned, individuals scoring high on national narcissism have significant deficiencies in the ability to distinguish between real and imaginary threats (Cichocka et al., 2022; Marchlewska et al., 2019), which in terms of the signal detection theory could be labelled as a false alarm (i.e., claiming yes when the signal is absent). Thus, national narcissism should be therefore related to asserting knowledge about concepts that do not exist, which is frequently labeled as overclaiming. Paulhus et al. (2003) developed the overclaiming technique, in which respondents are presented with a range of different items, but some of them are real and some are foils. Each participant is asked to rate their familiarity with each item, and on the basis of the responses provided it is possible to distinguish two different types of indexes: knowledge accuracy and response bias. Accuracy reflects not only the degree to which respondents indicate familiarity with a real item, but also the degree to which participants refrain from claiming familiarity with foils (Paulhus, 2012). In turn, the index of bias reflects the extent to which participants are eager to claim familiarity with all items (real and foils).

Propensity to overclaim knowledge has common correlates with national narcissism. For instance, individuals who overclaim religious knowledge are also more likely to support and engage in religious aggression (Jones et al., 2020), while individuals who score high on national narcissism are more likely to support military aggression (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). Both overclaiming and national narcissism have been found to be positively related to an increased propensity to believe in fake news (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021; Pennycook & Rand, 2018). Furthermore, overclaiming knowledge predicts anti-establishment voting, particularly the radical right (van Prooijen et al., 2019), as does national narcissism (Marchlewska et al., 2017). Thus, there is a considerable amount of evidence to expect that national narcissism will be characterized by a higher tendency to overclaim one’s knowledge, which we assessed in the current study.

CURRENT STUDY

Existing literature suggests that there should be a positive relationship between national narcissism and the tendency to overstate one’s knowledge, particularly in relation to concepts associated with the nation (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021; Jones et al., 2020; Marchlewska et al., 2017; Pennycook & Rand, 2020; van Prooijen et al., 2019). Thus, we expected that national narcissism would be positively related to response bias (H1) and negatively related to knowledge accuracy (H2). Furthermore, although we expected that individuals scoring high on national narcissism might declare their interest in their nation’s history, we expected that such interest would merely be a self-declared and superficial presentation. Thus, we expected that national narcissism would be related to interest in the nation’s history (H3) and that this relation would be effectively reduced to zero by partialing out the shared variance with the actual ability to distinguish between real and foil historical events (i.e., overclaiming, H4). In other words, we predicted that individuals scoring high on national narcissism would hypocritically proclaim interest and knowledge about their own nation. Data used in the current manuscript are available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) project site: https://osf.io/pk5cr/

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

Data for both studies were collected through an online survey (computer-assisted web interviewing – CAWI), conducted by an external research company on a nationwide sample of adult Poles, representative in terms of gender, age, and settlement size. All of the measures presented below were administered in Polish and each participant had the opportunity to quit the session without any consequences, as we did not collect any partial responses. Given the overarching goals of the study, we did not accept any data from individuals who did not declare Polish citizenship. Within the first study, we gathered data from N = 633 participants (53.1% females) aged from 18 to 81 (M = 47.93, SD = 16.52). In the second study, we gathered data from N = 1504 participants (52.3% females) aged between 18 and 96 years (M = 46.10, SD = 16.06).

MEASURES

National narcissism. In both studies, national narcissism was measured using the brief five-item version of the Collective Narcissism Scale, with nation as the reference group (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). Respondents indicated the extent to which they agreed with each of the statements using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Internal consistency estimates were very good in both studies: α1 = .89, α2 = .93.

National identification. In both studies, national identification was measured using the 12-items Social Identification Scale (Cameron, 2004; Polish adaptation: Górska et al., 2020). As previously, participants also rated their agreement with all items using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Internal consistency estimates were very good in both studies: α1 = .86, α2 = .82.

Self-reported interest in national history. It was measured with one item (i.e., “How would you rate your interest in the history of your nation?”) with responses ranging from 1 (i.e., very high, I am interested in almost everything regarding history) to 5 (i.e., none, history does not interest me at all). For presentation of the results, we reverse-coded this scale so a higher score reflected greater self-declared interest in history.

National knowledge overclaiming. Individuals are most likely to self-enhance on ego-relevant topics when they appear more central to the concept of the self; thus, for the purposes of the current study, we modified the overclaiming task (Paulhus et al., 2003; Paulhus, 2012) and asked the participants about the history of Poland and the knowledge about the organization of Polish political system. We developed 30 items, out of which six were foils (for the full list of items, see the OSF project site). Participants were asked to rate the degree of familiarity with each item ranging from 0 (never heard of it) to 6 (very familiar). Next, using the signal detection formulas, we calculated two sorts of common-sense indicators: accuracy (i.e., the ability to distinguish real items from foils) and bias (i.e., the tendency to rate non-existing items as familiar). The whole scoring procedure was based on Jones et al. (2020) and is uploaded to the OSF.

RESULTS

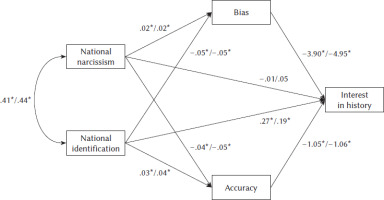

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are presented in Table 1. Across both studies, we found nearly identical results. Specifically, national narcissism was found to be positively associated with national identification. Both national narcissism (supporting H3) and national identification were found to be positively related to the self-declared interest in national history. However, while national narcissism was negatively associated with the ability to distinguish real items from foils, national identification was negatively related to the tendency to claim familiarity with the non-existing items. Next, using the PROCESS macro (model 4, Hayes, 2013) we assessed whether partialing out the variance shared between national narcissism and overclaiming would effectively reduce the strength of the relationship between national narcissism and the self-reported interest in national history. A graphical representation of the tested model is presented in Figure 1. The confidence intervals were based on 5,000 bootstrapped resamples. The analyzed mediation model was significant in both studies (F(4, 628) = 37.72, p < .001, F(2, 1501) = 82.68, p < .001), explaining 19.37% and 9.92% of the variance, respectively. After accounting for the shared variance between national narcissism and national identification, we also found full support for H1 (i.e., national narcissism was positively related to response bias) as well as H2 (i.e., national narcissism was negatively related to knowledge accuracy). Whereas the indirect effects from national narcissism on interest in national history either via accuracy (Study 1 = .04, 95% CI [0.01; 0.07], Study 2 = .05, 95% CI [0.03; 0.07]) or bias (Study 1 = –.09, 95% CI [–0.12; –0.05], Study 2 = –.09, 95% CI [–0.12; –0.07]) were both significant, the direct effect of national narcissism on interest in national history was non-significant in both studies, confirming H4. As for the other estimates, both response bias and knowledge accuracy were in turn positively related to the self-declared interest in history. We also observed one additional significant effect: national identification was positively related to the ability to properly distinguish real items from foils.

Figure 1

Relationship of national narcissism and national identification with interest in national history after partialing out the shared variance with overclaiming

Note. Results from Study 1 and Study 2 are separated by /. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing applied – estimates with p < .01 are marked as significant with *.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of study variables

DISCUSSION

People differ not only in how they identify with their nation (Petrovska, 2023) but also in how they view their nation’s history (Wójcik & Lewicka, 2022). In the current study, we scrutinized this issue, assessing how and why different types of national identity are related to the declared interest in the nation’s history. In line with extant literature, we found that national narcissism and national identification were positively related to one another (Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Marchlewska et al., 2022) and both were positively related to the self-declared interest in national history. Nevertheless, an examination of the relationship between different types of national identity and national knowledge overclaiming revealed that those who narcissistically identified with their nation claimed this interest hypocritically. That is, national narcissism was positively associated with knowledge bias (i.e., claiming familiarity with non-existing events) but also was negatively associated with knowledge accuracy (i.e., claiming familiarity with existing events and refraining from claiming familiarity with foils; Paulhus, 2012). Finally, we demonstrated that the observed relationship between national narcissism and self-declared interest in the nation’s history was reduced to zero when accounting for the shared variance between national narcissism and the tendency to overclaim one’s historical knowledge.

THE SUPERFICIAL CHARACTER OF NATIONAL NARCISSISM

National narcissism is related to an emotional investment in the perception that one’s nation is characterized by unparalleled greatness (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). To maintain such a grandiose image, those scoring high on national narcissism tend not only to idealize the past actions of one’s own nation (Bocian et al., 2021), but also to deny any historical facts that may distort such an exaggerated view (Klar & Bilewicz, 2017), which could be defined in terms of the self-positivity bias (Li & Nie, 2022). This could be interpreted in terms of a black-and-white thinking pattern (Stephens et al., 2021), in which WE are perceived as great, while OTHERS are seen as worse and hostile (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016). The results presented within the current manuscript somewhat question this line of interpretation. That is, if WE were important to those scoring high on national narcissism, they should not only be interested in our history, but they should also exhibit actual knowledge about it. We found, however, that national narcissism was related to overclaiming actual knowledge, which was characterized by higher bias and lower accuracy (Paulhus, 2012). Moreover, knowledge overclaiming explained the observed relationship between national narcissism and interest in national history, emphasizing that those scoring high on national narcissism are interested in THEMSELVES rather than US. In contrast, those who authentically identified with their nation (Cichocka, 2016) not only declared their interest in national history but were also characterized by lower knowledge bias and higher accuracy.

Studies on individual narcissism help to interpret such a paradoxical situation, in which people declare being interested in one’s nation’s history and at the same time possess lower levels of knowledge on that topic. Chen et al. (2021) reported that while individual narcissism was positively correlated with declared interest in politics, it was negatively related to actual political knowledge. Rogoza et al. (2022a) further explained this relation, claiming that while individual narcissism was related to political participation, this relation became non-significant after accounting for self-serving motives. In other words, those scoring high on individual narcissism engage in political life as long as it is beneficial for maintaining their grandiose self. Connecting these findings with the fact that those scoring high on national narcissism are prone to leaving US in favor of THEMSELVES (Marchlewska et al., 2020; Molenda et al., 2023) supports our claim that national narcissism is a superficial self-presentation tactic, driven by a grandiose group image, used to compensate for the vulnerable and fragile self (Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala et al., 2020; Marchlewska et al., 2024).

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Studying narcissistic identification with one’s nation is also important because of the fact that narcissistically identifying with one’s nation is strongly related to the endorsement of populist policies, support of violent extremism, and nationalism (Federico et al., 2023; Jaśko et al., 2020; Marchlewska et al., 2017). Similarly, as in national narcissism, the dominant need underlying violent extremism is the need for personal significance (Kruglanski et al., 2018; Marchlewska et al., 2024). Extremist ideologies could be described in terms of black and white thinking, resulting in a high level of confidence about the rightfulness of the undertaken actions (Stephens et al., 2021). However, are these actions underpinned by knowledge and a deep understanding of the problem? The results reported within the current study suggest that they are not. Although extremists frequently use national symbols to demonstrate their deep attachment to the nation, it appears that this attachment is only a façade. That is, the declared level of attachment towards the nation does not follow knowledge about the nation. Thus, emphasizing that this type of attachment is superficial is important, as those representing nationalistic attitudes tend to usurp the right to use national symbols, deterring a large part of society. This is, for instance, expressed in the results of an experimental study which revealed that exposure to the American flag increased nationalism but not patriotism (Kemmelmeier & Winter, 2008). Therefore, the results regarding national narcissism presented within the current manuscript also help to reveal the processes underlying national narcissism, and as a result, they might help bring the national symbols closer to society.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The main limitation of the current study is that we solely relied on cross-sectional data. Even if application of the tested model (i.e., mediation) may suggest a causal interpretation, we strongly recommend cautious interpretation of these results. In other words, we suggest interpreting the results of the mediation model in terms of regression-based analysis which helped to answer the question whether national narcissism would be related to interest in one’s nation’s history after taking into account its shared variance with overclaiming. Furthermore, the overclaiming task was developed specifically for the purposes of the current study. Although we pre-emptively addressed this issue through replication of our findings, future research might further explore the nature of overclaiming in national narcissism. Future studies might specifically assess whether overclaiming is more present when referring to positive events as compared to negative ones. Perhaps individuals scoring high on national narcissism might be more willing to overclaim knowledge when the presenting stimuli present one nation in a more favorable light while the relation would be weaker when referring to negative events (cf., Bocian et al., 2021; Klar & Bilewicz, 2017). Future research might also consider increasing the generalizability of our findings. The set task was specifically developed for the Polish population, and so we only accepted responses from Poles. While the task cannot be directly translated as it refers to events from the history of Poland, it might serve as a source of inspiration for developing a version tailored for a different nation.