BACKGROUND

Prosocial behavior, expressed in voluntary actions that benefit others, is a foundation of social life (Keltner et al., 2014). It includes a range of activities such as helping, sharing, caring, comforting, and donating (Laguna et al., 2022), which are beneficial to society, especially in threatening situations such as those caused by war. It is therefore important to better understand the mechanisms that stimulate such behavior, and emotions play a crucial role in this (van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022).

Previous studies have described the emotional benefits of acting prosocially and the intrapsychic costs of failing to do so (see Keltner et al., 2014), but much less is known about how the experience of specific emotions influences people’s prosocial behavior, and yet “the role of emotions in regulating prosocial behavior remains imperfectly understood” (van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022, p. 80). To fill this gap, we examine the role of pride in stimulating prosocial behavior.

Pride is usually considered a positive emotion felt in response to personal achievement (Dickens & Murphy, 2023). As there are generational shifts nowadays, with increasing emphasis on achievements, self-interest, and decreasing concern for others (Twenge et al., 2012), a better understanding of the role of pride in prosocial behavior is of societal importance in a rapidly changing world. We present two studies examining the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior, a correlational study conducted in a natural situation of dealing with war, and a laboratory experiment manipulating the level of pride. Consequently, we extend the limited empirical evidence on the role of pride in social interactions.

PRIDE AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Emotions are motivational factors that stimulate individual behavior and predict the choice, intensity, and persistence of actions, including prosocial actions (van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022). The historical focus on negative emotions has recently shifted to an interest in the emotions people experience when socializing, loving, relaxing, or achieving a vital goal (Chung et al., 2022). The exploration of positive and social emotions may be particularly important in explaining prosocial actions (e.g., Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020). Positively valenced emotions have been recognized as drivers of prosocial behavior, increasing the likelihood of adaptive behaviors such as sociability (Diener et al., 2015) and stimulating prosocial goal realization (Laguna et al., 2022).

Pride is typically conceptualized as a positively valenced, self-conscious, discrete emotion (e.g., Chung et al., 2022; Dickens & Murphy, 2023; Mercadante et al., 2021). Self-conscious emotions, including pride, require both self-reflection (e.g., “Is this event important to me?”) and self-evaluation (e.g., “How does this event make me feel about myself?”) (Chung et al., 2022). Discrete emotions are theorized to be evolutionarily adaptive, helping people achieve physically and socially important goals (Chung et al., 2022; Keltner et al., 2014). Discrete emotions, particularly those that are social in nature (van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022), are considered crucial to how people relate to themselves and others. Pride occurs when there is an opportunity for reward and is subjectively experienced as pleasurable (Chung et al., 2022), accompanied by feelings of being strong, confident, daring, and fearless (Watson et al., 1988). When a person feels proud, they are likely to have achieved a personal goal and attribute their positive feelings to the effort they put into something they value. Tracy and Robins (2007) proposed that pride consists of two facets – authentic pride and hubristic pride – but the conceptualization and especially the measurement of these two facets has recently been questioned (Dickens & Murphy, 2023). As Dickens and Murphy (2023) pointed out, pride should be captured as an emotion of positive valence, felt in response to the success that the person attributes to himself or herself, and hubristic pride does not meet these criteria. Therefore, our research is based on conceptualizing pride as a positive, self-conscious, discrete emotion that can be identified with the authentic facet distinguished by Tracy and Robins (2007).

Research has shown that pride is an important motivator in social life. It is experienced when adhering to social norms and expectations (Sabato & Eyal, 2022). It encourages people to continue the valued behavior (see Tangney et al., 2007) and is an internal reinforcement to motivate moral behavior (Pascual et al., 2020). It also induces people to incur short-term costs to obtain long-term rewards and motivates or reinforces behaviors that are valued in a social group (Williams & DeSteno, 2008, 2009). Pride (operationalized as authentic pride) is also positively correlated with adaptive personality traits such as agreeableness, extraversion, or conscientiousness (Dickens & Robins, 2022; Ding & Liu, 2022).

Rare studies of the relationships between pride and prosocial behavior generally show their positive associations. Moral pride has been shown to be positively correlated with prosocial behaviors, such as helping others or behaving fairly toward others, especially when accompanied by empathy (Ortiz Barón et al., 2018). Employees who felt pride were more likely to help their colleagues at work (Kim et al., 2018), and leaders’ authentic pride was positively related to their prosocial behavior (Michie, 2009). One form of prosocial behavior is volunteering; it increases one’s sense of pride, and increased pride, in turn, leads to a greater willingness to volunteer (Septianto et al., 2018). Some studies suggest that feelings of pride are positively correlated with prosocial behavior, such as generosity (see Tangney et al., 2007), and positively influence the decision to donate, but not the amount donated (Paramita et al., 2020). However, not all studies provide evidence of positive associations between pride and prosocial behavior. For example, the results of two studies by Etxebarria et al. (2015) were contradictory: one study confirmed the hypothesis that pride experienced after performing a prosocial behavior increases the intention to perform another prosocial action, while the second study did not support this hypothesis – children who recalled situations in which they experienced moral pride did not show a greater intention to engage in prosocial behavior than those who recalled neutral situations. Despite some progress, empirical evidence on the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior is mixed and limited, which does not guarantee firm conclusions regarding the role of this emotion, especially in stimulating behavior toward others (see van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022). In addition, some of the previous studies have relied on declared prosociality. To provide new evidence for the role of pride in actual prosocial behavior, we conducted two studies: a correlational study in natural settings and a laboratory experiment.

CURRENT RESEARCH

In two studies, we examined the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior, intending to capture actual behavior. In Study 1, we looked at helping Ukrainian refugees in Poland (the neighboring country) at the beginning of the war in Ukraine in 2022. Pride equips a person with the ability and psychological resources to help others (Dickens & Robins, 2022; Ding & Liu, 2022), and the level of sharing behavior is higher in volunteers than in non-volunteers (Nowakowska, 2022). In addition, people are more likely to volunteer because volunteering gives them a sense of pride (Hart & Matsuba, 2007), and an increased sense of pride increases their willingness to volunteer (Septianto et al., 2018). Based on this and the explanations provided in the previous section, we hypothesized that:

H1: There is a positive relationship between pride and prosocial behavior expressed in helping Ukrainian refugees.

Pride can activate people’s motivation to engage in behaviors that are highly valued by others and to conform to social norms (Tangney et al., 2007). Studies suggest that pride increases moral actions (Hart & Matsuba, 2007; Tangney et al., 2007; Tracy & Robins, 2007), and proud individuals are more likely to donate and may believe that doing so will improve their social status, as charitable behavior is considered noble (Griskevicius & Kenrick, 2013). Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H2: The experience of pride increases prosocial behavior.

STUDY 1

This study analyzed the relationship between pride and helping behavior for refugees from Ukraine who left their country as a result of Russia’s aggression that began on February 24, 2022. It tested hypothesis H1.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

The on-line survey was targeted at Polish-speaking adults in Poland. The link to the survey was shared on social media on March 4-11, 2022, during the second week of the armed conflict in Ukraine. The average daily inflow of refugees to Poland at that time was 115.9 thousand people (SD = 60.45 thousand)1. The questionnaire reached 923 people, 365 of whom provided complete answers.

PARTICIPANTS

The survey included 365 people (74.8% women) aged 16-34 years (M = 22.58, SD = 3.99). Respondents lived in a city with 101,000 to 500,000 inhabitants (30.7%), a village (29.3%), a city with more than 500,000 inhabitants (18.1%), a city with 21,000 to 100,000 inhabitants (15.6%), or a city with up to 20,000 inhabitants (6.3%). They had secondary education (53.7%), higher education (34.5%), primary education (9.6%), or vocational education (2.2%). More than half of the respondents (57%) identified themselves as religious believers.

MEASURES

Pride. To measure pride, the Self-assurance subscale from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson et al., 1988) expanded version (PANAS-X), Polish adaptation (Fajkowska & Marszał-Wiśniewska, 2009) was used. It contains six adjectives (e.g., proud, confident). Respondents answered to what extent they had felt these emotions in the past week on a five-point scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). The reliability of the scale was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha α = .87.

Prosocial behavior was measured by the question: “Since the beginning of the armed conflict in Ukraine (2/24/2022), have you been involved in helping Ukrainian refugees?” with two response options (yes, no). Time spent helping was measured by the question: “In total, how many hours did you spend helping Ukrainian refugees in the last week?” with five answers: less than 1, 1-3, 4-6, 7-9, and more than 12.

DATA ANALYSIS

Statistics on the distribution of the variables were analyzed, and correlation analysis was performed to verify hypothesis H1. For the relationship between pride and involvement in helping (measured on a nominal scale), the correlation ratio eta coefficient (η) was used. For the relationship between pride and time spent helping (measured on an ordinal scale), the Kendall rank correlation coefficient tau-b (τb) was used.

RESULTS

Involvement in helping activities was reported by 269 people (73.7% of the sample). Of these, 90 people reported spending 1 hour per week helping, 101 people 1-3 hours, 49 people 4-6 hours, and 19 people 7 or more hours. For pride, the mean was 2.74 (SD = 0.82).

The results of the correlation analysis showed a weak association between pride and involvement in helping (η = .22) and a statistically significant positive but weak correlation between pride and the number of hours spent helping (τb = .21, p < .001). Thus, hypothesis H1 was confirmed – the more intensely a person experienced pride, the more often they engaged in helping Ukrainian refugees and the more time they spent on those activities.

A moderator analysis was conducted to test whether additional variables influence the relationship between pride and involvement in helping. Moderators such as sex (female/male), religiosity (non-believer/believer), and place of residence (cities up to 100,000/over 100,000) were tested. Model 1 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) was used. Each of these variables was a non-significant moderator2. This shows that the results are generalizable to men and women, non-believers and believers, and adults living in small and large cities.

STUDY 2

This study tested hypothesis H2 with respect to two indicators of prosocial behavior: the amount of money donated to charity and the number of leaflets taken to help recruit for the study.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PILOT STUDY

The purpose of the pilot study was to test the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation (see the Procedure section below). The study involved 40 students (76.2% female) aged 19-24 years (M = 20.83, SD = 1.25) randomly assigned to two groups. In the experimental group, participants were asked to recall a situation in which they felt pride; in the control group participants were asked to recall the room they were in, and to describe the memory (handwriting, at least 5 lines, a method often used to induce emotions, e.g., Maslej et al., 2020; Śmieja-Nęcka et al., 2022). The level of perceived pride was then measured using the PANAS-X scale (the same as in Study 1). The mean level of pride in the experimental group (M = 3.92, SD = 0.74) was significantly higher (t = 4.80, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.54) than in the control group (M = 2.51, SD = 1.09). Thus, the manipulation proved to be effective.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were 82 students (57.3% female) aged 18-26 years (M = 21.30, SD = 1.71) from universities in Lublin, Poland. Most came from rural areas (42.7%) and cities with 101-500,000 inhabitants (26.8%), the rest from cities with 21-100,000 inhabitants (13.4%), up to 20,000 inhabitants (12.2%), and over 500,000 inhabitants (4.9%). The majority of respondents (80.5%) identified themselves as religious believers.

PROCEDURE

Information about the experiment was disseminated through social media and leaflets. Students were informed about the compensation of PLN 20 for participation. Only (1) students, (2) aged 18-30 years, and (3) not studying psychology in their 2nd or higher year were enrolled. Those who met these three criteria chose a convenient time to visit the university laboratory.

Before the experimental manipulation, the experimenter randomly assigned the participant to an experimental or control condition using an electronic device and asked them to perform tasks presented on a monitor. The experimenter then left the room and the participant began the survey by giving informed consent to participate in the experiment and was informed that he/she could opt out at any stage of the experiment. Each participant also filled in some questions (e.g., concerning demographics), and then was asked to complete a task on a piece of paper, writing at least 5 lines of text. In the experimental group, the definition of pride was presented and participants were asked to close their eyes and recall a situation in which they felt pride. If they recalled several situations, they were asked to focus on one and empathize with the emotions that accompanied the event. In the control group, the participants were given the task to look around the room they were in for one minute, trying to remember as many details as possible, and then, without looking around again, to recall and describe the room. After writing down the text, participants from both groups answered on a computer questions about the difficulty and vividness of the memory and completed the PANAS-X scale, describing the emotions they felt at that moment.

After completing the task, participants were instructed to inform the experimenter who entered the room and gave the respondent a reward of PLN 20 in nominal value: PLN 1, 2, 2, 5, 10. Then the experimenter announced that we were collecting money for the needy and showed the charity box next to the computer. Then, under the pretext of forgetting the leaflets, they left the room (to leave the participant alone to decide about the donation). After about 30 seconds, the experimenter returned with a box of leaflets, saying that we needed help to reach more respondents and that the participant could take some. The participant decided whether to take the leaflets and how many to take.

After the participant left, the experimenter recorded the amount of the donation, the number of leaflets taken, and the number of lines of text written by the respondent.

OPERATIONALIZATION OF VARIABLES

Prosocial behavior was operationalized as (1) the amount of money the respondent donated to a charitable organization and (2) the number of leaflets taken to help the experimenters reach more potential respondents.

The independent variable was an experimental manipulation, the recall of an event in which the respondent experienced pride (or a room, in the control condition). The Self-assurance scale of the PANAS-X, described in Study 1, was used to measure the effectiveness of the manipulation. Reliability α = .90.

The vividness of the memory (“How vivid was the memory you recalled?”) and the difficulty of recall (“How difficult was it for you to recall it?”) were also controlled in the experiment, with responses provided on a 5-point scale (1 – not at all clear, 5 – very clear, and 1 – very difficult, 5 – very easy, respectively).

DATA ANALYSIS

First, the effectiveness of randomization was tested by comparing the experimental and control groups in terms of demographics. Next, the effectiveness of the experimental procedure was tested by examining whether the groups differed in terms of experienced pride, as well as vividness of memory, difficulty of recall, and length of text written. The independent samples t-test was used to verify hypothesis H2.

RESULTS

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

The experimental and control groups were not significantly different in terms of sex ratio (χ2(1) = 3.17, p = .389), place of residence (χ2(4) = 6.45, p = .168), education (χ2(2) = 1.73, p = .421), being a believer (χ2(1) = 3.17, p = .075), or age (t = –1.46, p = .150). This means that randomization was effective.

Next, differences between groups were tested for the formal aspect of their memories. The analysis showed no statistically significant difference in vividness of recall (t = 1.58, p = .059), difficulty of recall (t = 1.49, p = .140), or number of lines of text written (t = 0.77, p = .444).

A significant difference was observed in the level of pride felt after writing down the memory (t = 3.75, p < .001, d = 0.83). A higher level of pride was recorded in the experimental group (M = 23.78, SD = 4.06) than in the control group (M = 19.67, SD = 5.68), indicating that the experimental manipulation was highly effective.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING

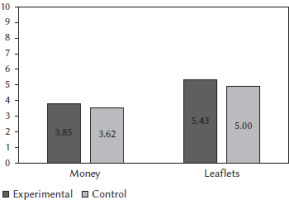

The effects of pride on prosocial behavior were tested for each of the two operationalizations. Regarding the amount of money donated to charity, people in the experimental group donated a total of PLN 154, while people in the control group donated a total of PLN 152. There was no significant difference in the amount of money donated (t = 0.22, p = .826) between the experimental group (M = 3.85, SD = 4.66) and the control group (M = 3.62, SD = 4.80). The emotional state induced by the manipulation had no effect on the amount donated (Figure 1). In addition, the dependent variable was transformed into a dichotomous variable (no donation/a donation). The analysis also showed no difference between groups (χ2(1) = 0.09, p = .759).

Regarding the number of leaflets taken, the experimental group took a total of 217 leaflets, while the control group took 210 leaflets. The analysis showed no significant difference (t = 0.37, p = .714) between the experimental group (M = 5.43, SD = 5.72) and the control group (M = 5.00, SD = 4.71; Figure 1). In addition, after dichotomizing the dependent variable (took no leaflets/took at least one leaflet), no difference was observed between groups (χ2(1) = 0.01, p = .942).

Figure 1

Average values of the amount of money donated to charity and the number of leaflets taken to help recruit for the study in the experimental and control groups

All of these analyses indicated that experiencing experimentally evoked pride did not affect prosocial behavior. Hypothesis H2 was therefore rejected.

DISCUSSION

In two studies, we examined the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior, intending to measure actual behavior, not declared prosociality, and ensuring high ecological validity. The results of Study 1 showed a weak relationship between pride and involvement in helping Ukrainian refugees who left their country as a result of Russian aggression in 2022, and a positive but weak relationship between pride and the number of hours spent helping. In experimental Study 2, the level of pride was manipulated by recalling an event in which the person felt this emotion (recalling the room in the control condition); the effectiveness of this manipulation was confirmed in a pilot study. The results showed that the experimental and control groups did not differ in the amount of money they donated to charity and the number of leaflets they picked up to help recruit for the study.

The results of Study 1 supported hypothesis H1, indicating that pride is correlated, albeit weakly, with helping behavior and the number of hours spent helping. Similarly, a previous study found that experiencing pride was conducive to spending more time volunteering (Hart & Matsuba, 2007). This suggests that pride is related to time dedicated to helping. Independent of the main analyses, Study 1 provided unique information about the involvement of Poles in helping Ukrainian refugees during the first weeks of the war.

However, the results of Study 2 did not support hypothesis H2, as the experience of pride had no effect on prosocial behavior. Paramita et al. (2020) found that pride positively influenced the decision to donate, but not the amount donated. This justified the decision to dichotomize the charitable donation variable in Study 2 but still did not support hypothesis H2.

Therefore, the results of our two studies are not consistent. The differences between the results of the correlational study and the experimental study may be due to the different methodologies and contexts in which the studies were conducted. Study 1 referred to a real-life situation in which individuals could engage in helping people – refugees escaping their country – behavior performed recently, within a specified period of time. Study 2 was conducted in laboratory settings that, despite efforts, may have seemed artificial, but it measured actual behavior, not declarations. These differences in methodology may have affected the results. Inconsistencies in the results of the two studies were observed also by Etxebarria et al. (2015), who used a similar emotion elicitation method as in Study 2. It is likely that effects of pride on prosocial behavior depend on the context and the type of prosocial behavior being assessed. Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that the correlation observed in Study 1 indicates an increase in pride after, rather than before, prosocial behavior, as observed in other studies indicating that volunteering gives people a sense of pride (Hart & Matsuba, 2007), which in turn increases their willingness to volunteer (Septianto et al., 2018). This suggests that further research is needed to better understand the effects of pride.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This study has several limitations that provide opportunities for future research. From a theoretical perspective, it is worth reconsidering the causal direction of the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior. In Study 1 we looked for correlations, and in Study 2 we tested the effects of evoked pride on prosocial behavior. However, it is likely that pride results from prosocial acts (Hart & Matsuba, 2007) or that they form a virtuous cycle. Further research is needed to test such effects.

Our research also has some methodological limitations. The first limitation is the demographic characteristics of the participants. Both studies included young people (up to 34 years of age). Research suggests that altruistic motivation increases with age (Sparrow et al., 2021), as does the tendency to conform one’s behavior to social norms (Knoll et al., 2017). Age-related access to resources (e.g., having one’s own money or home) may be important for prosocial behavior (Sparrow et al., 2021), and it can be hypothesized that older people would be more involved in helping than younger, which is worth considering in further research. In addition, the majority of respondents in Study 1 were women, which may be due to the fact that women are generally more likely to participate in psychological research. On the other hand, in Study 2, where the gender ratio was balanced, the participants were students. Thus, in future research, it would be advisable to ensure a more diverse composition of the sample.

Second, the measure of the number of leaflets taken in Study 2 may have been biased as some respondents reported that they would not take the leaflets because they had already sent their friends the link to the recruitment survey they received on social media. Nonetheless, this measure yielded the same results as the charitable donation measure. Further research will need to refine this method, although it is a useful way to target more participants.

Third, due to limited funding for rewarding participants (PLN 20 each) in Study 2, we were able to recruit a limited number of people. The post hoc power analysis (α = .05, f = .25; calculated using G*Power) showed that this study had a power of (1 – β) = .60. A larger number of participants could potentially result in statistically significant differences; however, this is not likely given the very small differences observed in this study between the mean levels of the dependent variables in the experimental and control groups (see Figure 1). To rule out this possibility, future studies will need to ensure a larger amount of money for experiments with financial rewards for participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Many questions remain to be answered. Nonetheless, the two studies presented here provide new evidence on the role of pride in actual prosocial behavior and extend the limited understanding of the role of pride in social interactions (van Kleef & Lelieveld, 2022). Despite the association between pride and engaging in helping others, experiencing pride does not reinforce the actual help. The inconsistent results of our research suggest that further studies are needed to better understand the relationship between pride and prosocial behavior.