BACKGROUND

CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION

The term ‘conspicuous consumption’ was used by Veblen (1899/1994) to describe a socially developed strategy for status enhancement. In this approach, the acquisition and display of expensive, luxury products operate as external signals of prestige due to the perceived social equilibrium between price and status. Higher-income groups use luxury goods to maintain their position and to enhance differences between them and the rest of the social strata. In turn, lower-income groups aspire to the living standard of higher-income groups and need the relevant goods to signal their position. Ordabayeva and Chandon (2011) demonstrated that increasing equality of material possessions or income in a social group reduces conspicuous consumption for people at the bottom of the distribution in a cooperative social context only when individuals do not care about the position. In turn, individuals with a low economic position who care about their status try to ‘keep up with the Joneses’ and spend a larger proportion of their budget on status-conferring consumption. Visible consumption of luxury products enables individuals to boost their status (Amatulli et al., 2015; Charles et al., 2009; Friehe & Mechtel, 2014; Kaus, 2013; Khamis et al., 2012; Kim & Jang, 2014; Mazzocco et al., 2012; O’Cass & McEwen, 2006; Ordabayeva & Chandon, 2011; Rucker & Galinsky, 2009; Saad & Vongas, 2009; Truong et al., 2008). Moreover, nowadays the nature of conspicuous consumption has become more discreet. It is not only wealth but taste that has gained in importance (Berger & Ward, 2010). Individuals with exclusive taste but less money might exhibit their uniqueness through product selection and usage (Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2010).

Data demonstrated that propensity to conspicuous consumption is rapidly growing in emerging countries (Podoshen et al., 2011; Souiden et al., 2011; Zhang & Wang, 2019). It occurs more in individualistic cultures than in collectivist cultures (Souiden et al., 2011). Furthermore, the acculturation of consumers towards western culture drives them to purchase the luxury of western fashion (Das & Jebarajakirthy, 2020). Poland is a developing country and individualistic as well. The luxury goods market in Poland is still increasing. In comparison with the previous year, its total value increased in 2019 by 5.4%. Luxury and premium cars are the largest segment, and hotel and spa services are among the fastest growing segments of the luxury goods market (KPMG, 2020).

NARCISSISM AND CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION

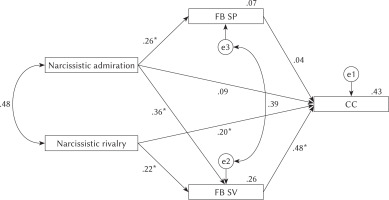

The concern for social status underlying conspicuous consumption is closely connected with a preoccupation with the public image, which is especially important for narcissistic people. The research focuses on relationships between narcissism, self-oriented activity on Facebook and conspicuous consumption. In recent years, the study of narcissism has shifted toward viewing subclinical levels of narcissism as points along a continuum. In most studies, narcissism is considered as a personality trait and measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Terry, 1988). In the present study, we focused on grandiose narcissism and treated it as a multidimensional construct as proposed by the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept (NARC; Back et al., 2013). The NARC is a multi-dimensional self-regulatory process model that distinguishes between two dimensions of grandiose narcissism: narcissistic admiration by self-enhancement and narcissistic rivalry driven by self-defence. The purpose of this research was to establish the direct impact of both narcissistic strategies on conspicuous consumption. Furthermore, we also examined the indirect impact of narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry on conspicuous consumption through self-oriented activity on Facebook.

Narcissism is a complex multifaceted phenomenon that refers to a normally distributed personality trait characterised by grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy (APA, 2013). Within this broadly defined construct exist two or more forms of narcissism, mainly referred to as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. The former is closely connected with grandiosity, arrogancy, envy, entitlement, aggression, and dominance. The latter is regarded as hypersensitive to criticism, a shy individual with a low tolerance for attention from others. The grandiose narcissistic individual is more likely to regulate self-esteem through overt self-enhancement and denial of weaknesses than a vulnerable narcissistic person (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller & Campbell, 2008; Russ et al., 2008; Wink, 1991).

Narcissism, conceptualized as a trait and widely measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), ranges on a continuum (Raskin & Terry, 1988). Its extreme intensity considered pathological is associated with a low level of mental health (Brown et al., 2009; Dixit et al., 2015; Sedikides et al., 2004). Furthermore, Ackerman et al. (2011) demonstrated that the NPI is composed of three distinct dimensions: Leadership/Authority, Grandiose Exhibitionism, and Entitlement/Exploitativeness. The last two dimensions, particularly Entitlement/Exploitativeness, are generally linked to maladaptive outcomes. The first dimension, characterized by perceived leadership abilities and social potency, is associated with adaptive results (Ackerman et al., 2011).

Back et al. (2013) described two distinct but inter-related strategies of grandiose narcissism: narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry; both serve to maintain a grandiose self. The NARC distinguishes different affective-motivational, cognitive, and behavioural domains of strategies. Striving for uniqueness (affective-motivational domain), together with grandiose fantasies (cognitive domain), triggers charmingness (behavioural domain), whereas striving for supremacy (affective-motivational domain) and devaluation of others (cognitive domain) induces aggressiveness (behavioural domain). Agentic narcissistic admiration driven by self-enhancement is mainly adaptive and links to the need to be unique. Antagonistic narcissistic rivalry driven by self-defence relates to the fear of self-status and hostility towards others. The purpose of narcissistic admiration is to gain social recognition and narcissistic rivalry is to prevent social failure. Narcissistic admiration reflects the extent to which an individual believes she/he is special and wants to be admired, whereas narcissistic rivalry reflects the extent to which an individual wants to be better than others. In line with the NARC assumptions, people differ in their propensity to maintain grandiose self-narcissism, and the extent to which they use narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry as well (Back et al., 2013).

Narcissists, to maintain a grandiose self, to get admiring responses from others, and to boost their status, may be prone to purchasing high-status goods. Flaunting material possessions allows them to communicate the uniqueness of the owner, arouse admiration and jealousy, and preserve an exaggerated self-image and power self-esteem (Sedikides et al., 2007). Narcissistic individuals may be prone to over-consumption because they seek products that help boost their self-esteem. Research indicates that narcissistic individuals may prefer expensive, luxury, exclusive, new, and flashy products (Pilch & Górnik-Durose, 2017; Sedikides et al., 2007). Cunningham-Kim and Darke (2011) found that people with high scores on the narcissism scale were more likely to choose prestigious products than those with low scores. The research also demonstrates that narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry are important predictors of a vain consumer style (Martin et al., 2019). Narcissists are also more likely to purchase rare products (Lee & Seidle, 2012). Lee et al. (2013) demonstrated that narcissists reported a great inclination to purchase products to satisfy their need for uniqueness. In particular, more narcissistic participants rated products that permit them to distinguish themselves from wearers more favourably than did less narcissistic participants. Furthermore, narcissists were more likely to buy an exclusive limited edition of the product and would be willing to pay a higher price for it (Lee et al., 2013). The need to be unique, as well as the need to demonstrate status and the need to be similar to significant others, is also responsible for the propensity to conspicuous consumption (Amaldoss & Jain, 2008; Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2006, 2010; Kastanakis & Balabanis, 2012, 2014; Leibenstein, 1950; Niesiobędzka, 2017; Tsai et al., 2013; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). The need to be unique underlies the snob effect and is associated with the search for unusual, original, and unique products. The desire to be fashionable and the need to belong to, and be approved by, aspirational groups are responsible for the bandwagon effect and manifest themselves in the search for fashionable products used by significant others (Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). Lambert et al. (2014) have shown that contrary to consumers with low scores on narcissism, consumers with high scores do not build and preserve deep and permanent relations with specific products and brands. Narcissists use products and brands, like other people, instrumentally to achieve specific goals. Their relationships with people and brands tend to be agentic and liquid. Narcissists express loyalty to brands as long as they bolster self-esteem, display desirable self, and strengthen their social position (Lambert et al., 2014). Narcissism is particularly prevalent among younger generations, such as millennials and generation Z consumers (Foster et al., 2003), that is, consumers who, by 2025, are projected to account for 45% of the global personal luxury goods market (Solomon, 2017).

SOCIAL MEDIA AND NARCISSISM

Nowadays, the capability of communicating consumption has substantially increased. Social media have become a primary arena for displaying goods and confirming an individual’s position within a status system. They provide a setting encouraging comparison in many domains because users constantly receive information about others, what they do, and how they present themselves. Furthermore, online interaction makes socially visible consumption easier than face-to-face interaction since it does not require the acquisition of luxury products but only displaying them as expensive.

Research demonstrated that social media activity intensity depends on age. The frequency of Facebook use is negatively related to age (McAndrew & Jeong, 2012). Younger Facebook users more often engage in photo activities, group interaction, seeking personal information (Ozimek & Bierhoff, 2016), and disclose more personal information than older users (Christofides et al., 2012). Furthermore, younger individuals are more prone to addictive social media use than older people (Andreassen et al., 2012, 2017).

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter establish a perfect milieu for status enhancement activity and provide vast opportunities to craft an idealised self through explicit and implicit cues, to include the most favourable information about oneself as well as the most attractive profile photo and other posted photos. Moreover, social media allow individuals to obtain quick social recognition from a very broad audience and to verify their self-image. It also enables entire control of self-image by filtering the information about oneself that the individual wishes to disseminate. The properties of social media used to facilitate strategic self-presentation are well recognised by narcissists. The literature demonstrates a positive relationship between narcissism and the intensity of social media usage (Davenport et al., 2014; Moon et al., 2016; Ryan & Xenos, 2011; Singh et al., 2018; Taylor & Strutton, 2016; Walters & Horton, 2015). Narcissists are often compulsive social media users (Andreassen et al., 2017). They profoundly engage in self-promotion activities on Facebook: often update their profile and profile picture (Carpenter, 2012; Panek et al., 2013), more frequently insert photos of only themselves (Bergman et al., 2011; McCain & Campbell, 2018; Mehdizadeh, 2010), and post photos emphasising their physical attractiveness (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; McCain & Campbell, 2018) and the attractiveness of their activities (McCain & Campbell, 2018). Moreover, a high level of narcissism is associated with the number of friends on Facebook (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Carpenter, 2012) and willingness to accept invitations from strangers. Narcissists are also more prone to regard social media as a crucial source of knowledge about themselves. As Carpenter (2012) demonstrated, for narcissists, it is important to know if anyone is saying anything about them on Facebook. Narcissism is also a significant predictor of the proportion of selfies on an Instagram account, the frequency of selfie postings (Moon et al., 2016), and the amount of time spent editing Instagram photos (Singh et al., 2018).

THE CURRENT STUDY

To the authors’ best knowledge, no studies have investigated the relationship between narcissistic admiration, narcissistic rivalry, self-oriented activity on social media, and conspicuous consumption. In line with previous research, we assumed positive relationships between both narcissist strategies and conspicuous consumption. Narcissistic admiration leads to social status-seeking consumption as a result of striving to be unique and grandiose fantasies (H1). In turn, striving for supremacy, supported by thoughts of devaluation of others, underlying narcissistic rivalry, strengthens the propensity to conspicuous consumption (H2). In line with the results of previous studies, we also expected that both strategies oriented towards the maintenance of a grandiose self would be positively related to self-oriented activity on Facebook. Narcissistic admiration intensifies the frequency of self-promoting and self-verified behaviours because such self-centred, attention-seeking activity enables one to maintain beliefs regarding being superior and unique, and allows for gaining social recognition (H3, H4). The purpose of narcissistic rivalry is to prevent social failure, and thus self-promotion and self-verified activity on Facebook would reduce the fear of self-status. Therefore, we assumed that narcissistic rivalry would intensify self-oriented behaviours on Facebook (H5, H6). Self-oriented behaviours on Facebook by strengthening propensity to upward comparison would also have a significant impact on conspicuous consumption. People demonstrate their luxury lifestyle and status by displaying glamorous brands, extraordinary holidays, and the foods they consume (Efendioglu, 2019). Heavy social media users have more opportunities to make comparisons with others, so they would display their lifestyle including their belongings to a greater extent than less frequent social media users. Previous studies have established that a higher frequency of daily social media usage is associated with a stronger propensity to conspicuous consumption (Thoumrungroje, 2014, 2018; Wai & Osman, 2019). Furthermore, the more people are involved in self-promotion activity on social media, the more they are prone to consume conspicuously (Widjajanta et al., 2018). In line with previous research, we assumed that self-oriented behaviours on Facebook would strengthen the propensity to conspicuous consumption (H7, H8).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The sample consisted of 323 young adults ranging from 19 to 26 years of age (M = 22.78, SD = 2.02), including n = 165 women and n = 158 men. All participants were Facebook users.

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted on a sample recruited from an online panel (Computer Assisted Web Interview conducted by the Polish Nationwide Research Panel). In the first step, participants were given a consent form that described their rights as research participants. The online survey began with a basic demographic item, then participants were asked to complete the Conspicuous Consumption Scale (CCS; Chung & Fischer, 2001), the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ; Back et al., 2013) and the questions regarding Facebook use (Carpenter, 2012). Participants received points for participating in the study and could exchange points for rewards or donate to charity after collecting the appropriate number of them. The data were collected over a two-week period, from 5 December to 19 December 2018.

MEASURES

Conspicuous consumption. To measure conspicuous consumption, the Conspicuous Consumption Scale (CCS) proposed by Chung and Fischer (2001) was used. The scale consisted of four items. Respondents assessed the extent to which they agree with each item on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (agree definitely). Conspicuous consumption scores were obtained by calculating the average score for each participant, such that higher scores indicated a greater propensity to conspicuous consumption. The reliability of the CCS in the study was excellent, α = .92.

Narcissism. Narcissism was evaluated through the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ; Back et al., 2013). NARQ consists of 18 items and measures two parts of grandiose narcissism: narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry. Items were scored on a scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 6 (agree completely). Mean scores were computed for narcissistic admiration and rivalry. A higher score indicated greater intensity of narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry. The reliability of the narcissistic admiration subscale in the study was α = .85, and the reliability of the narcissistic rivalry subscale was α = .87.

Self-oriented activity on Facebook. To measure self-promotion and self-verified activity on Facebook we used two questionnaires proposed by Carpenter (2012). Self-promotion activity (FB SP) was measured through four items (e.g. updating own profile, posting photographs of oneself). Participants estimated the frequency with which they engaged in these behaviours using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (several times a day). Self-verified behaviours on Facebook (FB SV) were also measured through 4 items (e.g. willingness to check opinions or any information about oneself). Participants assessed the extent to which they agree with each item on a five-point scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (agree completely). Mean scores were computed for self-promotion and self-verified behaviours on Facebook. The reliability of the questionnaire to measure self-promotion activity on Facebook in the study was satisfactory, α = .79, and the reliability of the questionnaire to measure self-verified behaviours was α = .85.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

An a priori G*Power 3.1 (Mayr et al., 2007) analysis was conducted to determine the suitable sample size. We used the suggested higher power criteria of .95 and a critical significance level of α of .05 to identify a medium effect size of f2 = .15. The total number of variables is 5. G*Power analysis with the above-mentioned parameters would demand a sample of at least 129 participants.

In the first step, mutual relationships between variables were examined with Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Next, structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to search for relations between variables using the AMOS program. Model parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood method (MLM). To assess the model’s proper adjustment to the data, the following indices were used: goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and relative chi-square (χ2/df). GFI ≥ .90 and CFI ≥ .95 values indicate good and adequate adjustment of the model to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values of χ2/df < 2 also suggest a good fit of the model to the data. RMSEA values < .08 can also be interpreted as a good fit to the data (Byrne, 2016; Kline, 2015).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and values of Pearson’s correlation coefficients. The correlation analysis showed significant positive relations between conspicuous consumption and two dimensions of narcissism: admiration (r = .42, p < .001) and rivalry (r = .43, p < .001). A strong positive correlation appeared between self-verified activity on Facebook and conspicuous consumption (r = .61, p < .001). There was also a positive relationship between conspicuous consumption and self-promotion behaviours on Facebook (r = .29, p < .001). Narcissistic admiration positively correlated with both self-promotion (r = .26, p < .001) and self-verified activity on Facebook (r = .47, p < .001). There also significant relationships between narcissistic rivalry and self-verified activity on Facebook (r = .38, p < .001), whereas the relationship between narcissistic rivalry and self-promotion behaviours on Facebook was insignificant (r = .07, p = .209) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between variables

| CC | N admiration | N rivalry | FB SP | FB SV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N admiration | .42** | ||||

| N rivalry | .43** | .48** | |||

| FB SP | .29** | .26** | .07 | ||

| FB SV | .61** | .47** | .38** | .43** | |

| M | 10.50 | 31.56 | 27.66 | 9.04 | 10.77 |

| SD | 4.10 | 6.84 | 7.81 | 3.25 | 3.55 |

A structural equation modelling analysis was used to examine in detail the directed and indirect relationships between narcissistic admiration, narcissistic rivalry, self-promotion activity, and self-verified activity on Facebook and conspicuous consumption. The first tested model included seven paths representing the eight hypotheses. The model fit was unacceptable, χ2(1) = 61.95, p < .001, χ2/df = 61.95, RMSEA = .443 (90% CI [.353, .540]), GFI = .93, AGFI = .01, CFI = .84. In the second tested model, we included the covariance between self-promotion activity, and self-verified activity on Facebook. The tested model involved six regression paths. The relationship between narcissistic rivalry and self-verified activity on Facebook was insignificant, so this path was excluded from the model. The second tested model turned out to fit the data very well, χ2(1) = 1.46, p = .226, χ2/df = 1.46, RMSEA = .038 (90% CI [.000, .016]), GFI = .998, AGFI = .973, CFI = .999.

The relation between narcissistic rivalry and conspicuous consumption was significant (β = .20, p < .001), contrary to the relation between narcissistic admiration and conspicuous consumption (β = .09, p = .099). Narcissistic rivalry related positively to self-verified activity on Facebook (β = .22, p < .001), the strongest predictor of conspicuous consumption in the group of young adults (β = .48, p < .001). The relation between narcissistic self-promotion activity on Facebook and conspicuous consumption was non-significant (β = .04, p = .383). Furthermore, a significant positive association was found between narcissistic admiration and self-promotion activity on Facebook (β = .26, p < .001) and self-verified activity on Facebook (β = .36, p < .001). The standardized indirect effect of narcissistic rivalry on conspicuous consumption was .10, and the total was .31. The standardized indirect effect of narcissistic admiration on conspicuous consumption was .19 and the total effect was .27. Figure 1 presents standard path indicators: standard regression indicators for one-way arrows and correlation indicators for two-way arrows. In total, narcissistic admiration, narcissistic rivalry, and self-verified activity on Facebook explained 43% of conspicuous consumption variance. In turn, narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry altogether explained 26% of self-verified activity on Facebook variance, and merely .07% of the variance of self-promotion activity on Facebook.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to explore relationships between narcissistic strategies, self-oriented activity on Facebook, and conspicuous consumption. Empirical support was found for the assumption that conspicuous consumption was predicted by narcissistic rivalry. The fear of self-status and hostility towards others lead narcissistic individuals towards status-conferring consumption. This finding is in line with previous reports that demonstrated the propensity of narcissistic individuals to consume expensive, luxurious, exclusive, and flashy products (Cunningham-Kim & Darke, 2011; Lee et al., 2013; Lee & Seidle, 2012; Pilch & Górnik-Durose, 2017; Sedikides et al., 2007). Surprisingly, the relationship between narcissistic admiration and conspicuous consumption was non-significant. The results of the study demonstrated that engagement in expensive, luxury consumption to signal one’s status predominantly serves narcissists to prevent social failure. The more individuals want to be better than others, the more they flaunt material possessions.

Although the direct impact of narcissistic admiration on conspicuous consumption was non-significant, this strategy influenced signal status consumption through self-verified behaviours on social media. Narcissistic admiration related positively to self-verified activity on Facebook, the strongest predictor of conspicuous consumption in the group of young adults. Striving for uniqueness together with grandiose fantasies enhanced the tendency to obtain feedback from other Facebook users, and to a lesser extent the frequency of self-promotion behaviour on Facebook. Self-promotion behaviours on Facebook appeared to be non-significant predictors of conspicuous consumption. The standardized indirect effect of narcissistic admiration on conspicuous consumption was .19 and the total effect was .27. When narcissistic admiration increased by 1 standard deviation, conspicuous consumption increased by .27 standard deviations, of which .08 standard deviations resulted from the direct effect of narcissistic admiration.

Empirical support was found for the assumption that narcissistic rivalry affects conspicuous consumption via self-verified activity on Facebook. Narcissistic rivalry was positively related to the propensity to regard Facebook as a source of knowledge about oneself, but to a lesser extent than narcissistic admiration. The standardized indirect effect of narcissistic rivalry on conspicuous consumption was .10, and the total was .31. When narcissistic rivalry increased by 1 standard deviation, conspicuous consumption increased totally by .31 standard deviations, whereas .21 standard deviations resulted from the direct effect of narcissistic rivalry. Furthermore, contrary to narcissistic admiration, narcissistic rivalry did not significantly influence either of the examined self-oriented activities on Facebook. Narcissistic rivalry was only related to self-verified activity on Facebook, and was not related to self-promotion activity on Facebook.

The study also provided empirical support for previously established positive relationships between narcissism and self-oriented activity on Facebook (Bergman et al., 2011; Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Carpenter, 2012; McCain & Campbell, 2018; Mehdizadeh, 2010; Panek et al., 2013). The obtained results demonstrated that narcissist admiration strengthens the tendency to regard Facebook as a ‘social mirror’. This finding suggests that narcissist engagement in control of self-image on Facebook is due to gaining social recognition to a greater extent than to preventing social failure. Social media properties that facilitate strategic self-presentation mainly recognise narcissists driven by self-enhancement. Narcissists driven by self-defensive engagement only engage in self-verified activity, i.e. checking comments about themselves on Facebook. Narcissistic rivalry was unrelated to self-promotion behaviours on Facebook: updating the profile and profile picture, posting self-related photos, and tagging posts and photos. One plausible explanation for this non-significant result is that the fear of social failure may inhibit more active establishment of self-image.

The results of this study demonstrated that self-verified activity on Facebook was the strongest predictor of conspicuous consumption. The tendency to check for comments about oneself on Facebook by strengthening the propensity to upward comparison encourages the acquisition and display of glamorous, luxury products, and brands. Contrary to previous research, this study did not show a positive relationship between involvement in self-promotion activity on social media and propensity to consume conspicuously. Self-promotion and self-verified behaviours on Facebook fall under the umbrella of self-oriented activity, but they are distinct. The latter is passive activity focused on monitoring information about oneself created by others. The former includes active behaviours oriented towards providing diverse information about one’s self. Self-disclosure does not automatically lead to favourable impressions. It requires strategic decisions on which information about one’s self to disclose, and how to do so, in alignment with the preferred image. Engagement in self-promotion requires continual data updating, posting attractive photos and riveting posts that catch others’ attention, while conducting self-verification. Research indicates that more and more people are falling into the trend of ‘passive Facebooking’, i.e. a decrease in the activity of users of the service, such that only 52% of Facebook users consider themselves active. The remainder rarely share posts, do not comment, and at most view the activity of others, and therefore we did not observe a significant relationship between involvement in self-promotion activity on Facebook and propensity to consume conspicuously.

Currently, the largest increases in the number of activities are recorded by services such as Instagram (Davenport et al., 2014; Halpern et al., 2016; Krause et al., 2019; Lee & Kim, 2020; Widjajanta et al., 2018). Widjajanta et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between conspicuous consumption and Instagram usage, whereas we focused on activity on Facebook. This study indicates that different functions of social media should be identified. Currently, Facebook performs communicative and informative functions, while Instagram’s functions can be described as promoting. Instagram is a space where individuals can present themselves to others and create their ideal image. It allows you to control your profile, interact with chosen people and, above all, advertise yourself and show your success to a wide audience. In this regard, researchers point out that Instagram has a real impact on increasing or decreasing self-esteem. Studies demonstrate that, on the one hand, it does not affect our mood much, but on the other hand, our mood very much depends on how we use it. The best indicator is whether we view or actively participate in Instagram (Krause et al., 2019; Lee & Kim, 2020).

The study has limitations that may point to interesting paths for future research projects. First, the study was completely self-report and cross-sectional and, as in all correlational studies, we cannot determine causality between the main constructs. Therefore, we suggest that future research in this area should employ the experimental method to manipulate narcissism. Also, a longitudinal study should be helpful to evaluate causal relationships between variables. Given the limited number of studies on relationships between narcissistic strategies, self-oriented activity on social media and conspicuous consumption, we believe it is valuable to explore relationships between these variables. Second, the respondents of our study were at the age of emerging adulthood, that is, people with lower earnings than the national population (Poland; Central Statistical Office, 2019). On one hand, young people have fewer disposable earnings to consume, but on the other, they are an attractive target for luxury product manufacturers, i.e. consumers who are projected to account for 45% of the global personal luxury goods market by 2025 (Solomon, 2017). In the study, we did not ask participants to estimate their subjective socioeconomic status (SES), a variable that might influence the result of the study. Thus, the study should also be conducted with older adults and with measurement of the perceived annual income, and investigate differences in the relationships of the variables studied. Future research should examine whether the results hold for all age groups and groups with different SES backgrounds. Perhaps the consistency in age may be considered an advantage, due to the significant association between social media activity intensity and age. Young people more often use Facebook, and engage in a wider range of activities, including self-oriented activity, than older users (Christofides et al., 2012; McAndrew & Jeong, 2012; Ozimek & Bierhoff, 2016).

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that there is a positive influence of the narcissistic strategies on conspicuous consumption through the self-oriented activity on Facebook. This shows that narcissistic rivalry directly affects the propensity to conspicuous consumption and likewise narcissistic admiration affects self-verified activity on Facebook. The involvement of Facebook usage in this manner increases the acquisition and display of expensive, luxury, glamorous products as external signals of prestige and status.