BACKGROUND

Volunteerism is a process that intends to be helpful and to benefit other people or ideas, is undertaken out of free will and by choice, often serving personal motives, needs, and values (Omoto & Packard, 2016). It is often performed within an organization, without expectation of any remuneration (Snyder & Omoto, 2008). Despite volunteers sometimes getting benefits, such as recognition or personal development opportunities, or even small material rewards, the volunteer effort does not stem from either reward expectation or a punishment avoidance tendency (Omoto & Packard, 2016). To call an action “volunteerism”, no pre-existing relationships between the person and the beneficiary should be present, which might lead to obligations to offer help (Musick & Wilson, 2007; Snyder & Omoto, 2007). Rarely is volunteerism a single act; usually it is based on continuous devotion of effort and time (Wilson, 2000). Volunteerism can be performed in a wide variety of settings (Yeung, 2017), and sometimes the volunteering contexts and activities performed by a single person can vary. The voluntary actions may however be researched generally, beyond the context of performed voluntary action, as a form of real-life devotion of time (Bussell & Forbes, 2002) to a prosocial or other noble cause. As such, it has been investigated in recent research, e.g., Kee and colleagues (2018) or Maki and colleagues (2016).

Many organizations rely on volunteers to perform their activities successfully (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al., 2015). Therefore, it is very important to work to diminish the number of dropouts from this activity (Dwiggins-Beeler et al., 2011). Management of issues surrounding volunteer commitment might be especially vital for organizations whose volunteers are young (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al., 2015). Volunteer motivations differ across the lifespan (Boling, 2005); therefore, investigating the potential correlates of volunteer engagement taking into account a specific age group is worthwhile. Young volunteers are not commonly investigated in volunteerism research (which is especially discussed for those between 15 and 24 years of age, Francis, 2011; Shields, 2009). They are however a special group of volunteers. Young volunteers tend to be less loyal to the causes and institutions they serve than other age groups (Hustinx, 2001; Rehberg, 2005; Shields, 2009), and they potentially have more time to spend on volunteering (Freeman, 1997). Shields (2009), in a review of the existing body of research, found that young volunteers prefer volunteering especially when improving the everyday lives of less fortunate people in local communities, when the outcomes of their work are tangible and when they can perceive that they make a difference. Young adults also tend to expect benefits from their volunteerism, e.g., financial or career benefits. However, their volunteer activity promotes volunteering in later life (Janoski et al., 1998). It is pointed out that the survival of nonprofit organizations in the long term relies on the sustained engagement of the young adults of today (Shields, 2009). Prosocial behaviors might have linkages to successful attainment of developmental tasks of early adulthood (for a review see Nowakowska, 2020a), and volunteering can be helpful in e.g., seeking relationships and affiliation within the peer group, finding meaning in life as well as enhancing career prospects. It is thus important to understand why this age group decides to become volunteers and to continuously engage so that organizations and their managers can establish effective, persistent relationships with them.

EMPATHY, ALTRUISM, AND VOLUNTEERISM

Empathy is a feeling of caring for others as a response to a perceived lack of welfare, and difficulties of others (Batson et al., 1988; Davis, 1996). It is a form of emotional activation (Dovidio, 1991). Empathy has two dimensions: affective (empathic concern and personal distress) and cognitive (perspective taking) (Davis et al., 1999; Lauterbach & Hosser, 2007).

Empathy is a source of moral development and it influences decision making (Lönnqvist et al., 2011; Silfver et al., 2008). It can be, for instance, important to predict deliberate engagement in situations in which people in need might be encountered (Davis et al., 1999). There is also evidence that empathy predicts whether an observer would provide help when confronted with a request to do so (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987). Empathic dispositions may also be linked to volunteering (Penner et al., 2005; Stolinski et al., 2004), including time spent volunteering and length of experience with volunteerism (Penner & Finkelstein, 1998) or activism and positive expectations regarding volunteerism (Barraza, 2011; Davis et al., 2003).

The empathy-altruism hypothesis (Batson et al., 1991, 2015) suggests that empathy evokes altruistic motivation to benefit the person to whom empathic feelings are directed. Helping, however, is a result of this interaction when it is perceived as possible, more positive than having another person help or not acting. Therefore, Batson’s theory understands helping as leading to positive outcomes for the helper (distress reduction, gaining rewards). However, the ultimate goal is to help another person in need, not to increase one’s own welfare.

Altruism is defined as behavior performed out of free will, motivated neither by avoidance of aversive stimuli nor reward anticipation (Carlo, 2006; Carlo et al., 1991). An act can be considered altruistic when meeting several criteria: (1) voluntary initiation by the helper, (2) intention of helping others, and (3) performed without expectation of reward from external sources (Sharabany & Bar-Tal, 1982).

Evidence for the empathy-altruism hypothesis can be found in numerous studies (Edele et al., 2013; Farrelly & Bennett, 2018; Klimecki et al., 2016; Pavey et al., 2012). Among the dimensions of empathy, empathic concern, which is an affective response to the feelings of a distressed person (Davis et al., 1999), is an especially important predictor of altruistic behaviors (Dovidio et al., 2006; Pavey et al., 2012). A similar pattern was observed for perspective taking (Persson & Kajonius, 2016).

Altruism as a trait predicts volunteer behavior (Mowen & Sujan, 2005). However, research based on tools other than self-reports (e.g., social value orientation – SVO – measures based on decomposed games) is still scarce. A decomposed game is a task in which a person chooses how to split resources (e.g., points, money) between oneself and another person (Messick & McClintock, 1968) and is used to assess SVOs, typically perfectly competitive to perfectly prosocial/altruistic (Murphy & Ackermann, 2014). Available data show that altruistic sharing behavior measured by a form of a decomposed game, a dictator game, was predicted by affective empathy (Edele et al., 2013). Additionally, McClintock and Allison (1989) found that SVO measured by a decomposed game can predict prosocial behavior in real life, such as volunteering as a research participant. Prosocial-oriented people spent more time volunteering than individualists or competitors.

However, it needs to be noted that the hypothesized link between empathy and altruistic behaviors may not always be present, especially when ecologically valid measures of altruistic behaviors are employed. For instance, Lönnqvist and Walkowitz (2019) suggested that compared to the control group, when empathy was manipulated, dictators felt greater empathy toward the unknown recipient of the money, but it did not affect the split of the money. Other experimental research by Farrelly & Bennett (2018) found that when empathic feelings were induced in participants, they spent more time on a quiz platform to help a real-life charity (donate grains of rice), but, when anger was also induced, the effect of empathy was not present. It suggests that when some other conditions are met, the linkage between empathy and altruistic behavior might be different than hypothesized by the empathy-altruism hypothesis. It would be interesting to examine whether the hypothesized positive link between empathy and altruism measured with an ecologically valid tool exists within a particular population of active, real-life volunteers. Volunteers, although probably high on empathy and altruism, perform a special form of helping – based on the devotion of time and efforts, and driven by both self- and other-oriented motives (Bussell & Forbes, 2002).

CURRENT STUDY

The aim of the current study is to find out whether the relationships between empathy and altruism are different in non-volunteers and people who volunteered in the last year. Based on the existing literature on volunteering, it was hypothesized that (H1) volunteers are higher on trait empathy and altruistic SVO than non-volunteers. Personality traits that foster helping might be antecedents of volunteer engagement (Omoto & Snyder, 1995) and may develop thanks to it as well as reinforcing this engagement (for a review of individual changes that can occur as a consequence of volunteerism, see Mateiu-Vescan et al., 2020). People, in general, tend to choose actions congruent with their personality traits (Snyder & Ickes, 1985), and volunteerism can be viewed as an emanation of high empathy and altruistic SVO in their real life. Interestingly, high and low committed volunteers are found not to differ in terms of their altruism or empathy (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al., 2015). Thus, in the current study, volunteers who were active in the last year, regardless of the frequency of their activity (at the same time, their engagement is relatively recent and can be considered a fresh experience), are compared to people who were not engaged in volunteerism in the last year. The rationale for taking into account volunteers who were active within a year prior to the study is that such an approach makes it possible to involve people who have been involved relatively recently. It is worth noting that some kinds of volunteering require action in a particular season or time (e.g., in the case of fundraising), but the engagement of a volunteer is recurrent (every year); thus, taking into account volunteers from a period of a year preceding the study makes it possible to take into account people who choose such seasonal activity, but exclude those who potentially opted out of the activity and/or their experience is more difficult to recall.

Empathy and altruism are positively associated (Batson et al., 2015) in studies in the general population. Although affective empathy predicts altruistic values better than cognitive empathy, both of the empathy forms can be hypothesized to predict altruism (Persson & Kajonius, 2016). For altruism, abundant data are available for altruism measured through self-report, language-reliant tools, which lack ecological validity and carry the risk of social desirability bias (Dziobek et al., 2008; Van Lange et al., 2007). Tools characteristic for game theory assess altruism at the behavioral level under defined, laboratory conditions (Edele et al., 2013), serving as standardized, reliable, and valid measures (Murphy & Ackermann, 2014). For volunteers, the linkage between empathy and altruism might not necessarily be present, especially when a decomposed game is used as an operationalization of altruism. Decomposed games are based on the allocation of resources (usually money) between oneself and another person (Murphy et al., 2011). Taking into account the conceptual difference between forms of helping – volunteerism (more long-term-oriented, requiring an effort) and sharing money (more short-term-oriented, requiring less personal effort) – it might be hypothesized that the relationship between empathy and altruism as measured by the SVO decomposed game measure might not be observable among volunteers. For instance, in a recent study by Nowakowska (2021), altruistic SVO was not related to frequency of volunteering in the year preceding the study. Moreover, research by Jasielska and Rajchert (2020) indicated a lack of significant correlation between SVO as measured with a decomposed game and communion, as well as a significant negative relationship between SVO and agency. Empathy displays positive correlations with communion as a personal attribute (Laurent & Hodges, 2009) and communal goals (Findley & Ojanen, 2013), which could suggest that empathy, similarly to communion orientation, could have no significant relations to SVO (Jasielska & Rajchert, 2020). It is worth noting that agency pertains to profitability to the self, whereas communion pertains to profitability to others (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007). However, both agency and communion predict interest in prosocial actions (Gebauer et al., 2014). Volunteering is a communion-oriented action requiring a sense of agency (feeling capable of doing work for the well-being of others, and real devotion of time and own work), profitable to both the self and others (MacNeela, 2008). In the light of the knowledge about SVOs measured by decomposed games and the characteristics of volunteer work, the question remains whether empathy can still significantly relate to SVO in volunteers. According to the literature review, no previous research has explored a potential moderating role of volunteerism participation in the relationship between empathy and altruistic SVO captured with a behavioral measure, such as a decomposed game. Given the exploratory nature of the study, a research question was posed (RQ1), whether volunteerism participation acts as a moderator between empathy and altruistic SVO.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

In total, 305 females (75.9%) and 97 males (24.1%) aged 18-35 (M = 23.23, SD = 3.65) took part in the study. A power analysis performed using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007, 2009) indicated that such a sample size enabled one to detect the effect of a partial R2 increase of .05 (α = .05) with a power of .97.

Non-volunteers. The non-volunteer group consisted of 224 participants aged 19-35 (M = 23.55, SD = 3.59), 164 females (73.2%) and 60 males (26.8%). Regarding the place of residence, 45 (20.1%) participants lived in a village, 53 (23.7%) in a town with less than 100 000 inhabitants, 40 (17.9%) in a town with 100 001-499 999 inhabitants, and 86 (38.4%) in a town with more than 500 000 inhabitants. Regarding education, 1 participant (0.4%) had finished high school, 115 (51.3%) BA studies, 75 (33.5%) MA studies, 31 (13.8%) PhD studies, and 2 (0.9%) reported other education status. Regarding experience with volunteering prior to the last year, 84 participants (20.9%) had never been volunteers in their lifetime, and the other 140 (34.8%) had not volunteered in the last year.

Volunteers. The volunteer group consisted of 178 participants aged 18-34 (M = 22.84, SD = 3.71), 141 females (79.2%) and 37 males (20.8%). Regarding place of residence, 32 (18.0%) lived in a village, 35 (19.7%) in a town with less than 100 000 inhabitants, 31 (17.4%) in a town with between 100 001-499 999 inhabitants, and 80 (44.9%) in a town with more than 500 000 inhabitants. Regarding education, 3 (1.7%) participants finished primary school, 2 (1.1%) vocational school, 1 (0.6%) high school, 104 (58.4%) BA studies, 44 (24.7%) MA studies, 23 (12.9%) PhD studies, and 1 (0.6%) reported other education status. Regarding volunteering frequency in the last year, 85 (47.8%) engaged had volunteered once or twice, 50 (28.1%) several times, 8 (4.5%) once a month, 13 (7.3%) 2-3 times a month, 10 (5.6%) once a week, and 12 (6.7%) more often than once a week.

For the volunteering fields, the volunteers could mark multiple pre-defined contexts in which they serve (medicine, education, ecology, local community service, office work, culture, charity), and/or write down other forms in which they engage. 28 participants (15.7%) were volunteers in the field of medicine, 64 (36.0%) in education, 23 (12.9%) in ecology, 55 (30.9%) in serving their local community, 14 (7.9%) in office work, 33 (18.5%) in culture, 100 (56.2%) in charity, and 19 (10.7%) in other forms of volunteerism.

MEASURES

The study was part of a larger project. Analyses based on the same dataset but focusing on different study variables and testing different research hypotheses will be reported elsewhere. The whole set consisted of questionnaires in the following, non-randomized order: demographic survey, Social Value Orientation Slider Measure (Murphy et al., 2011; Polish: Nowakowska, 2020b); Empathy Quotient-Short (Wakabayashi et al., 2006; Polish: Jankowiak-Siuda et al., 2017) and three additional questionnaires (measuring time perspectives, coping strategies and impulsivity) which are not part of the current analysis. In randomly selected places within the survey, three questions controlling attention were placed: “This question controls your attention. Mark (a defined option)”.

Social value orientation. SVO angle was computed based on 6 primary items of Social Value Orientation Slider Measure Version A (Murphy et al., 2011) with Polish instructions prepared by Nowakowska (2020b). A Social Value Orientation Slider Measure is a decomposed game. Each of the items is a continuum of forms of resource allocation (the resource is described as money). The participant has to choose the most preferred resource allocation between oneself and a fictitious “other”. Results obtained in this measure are computed with an algorithm (in the current study an automated computation algorithm for SPSS approved by the authors of the measure and shared by Baumgartner, n/d, was employed), resulting in an SVO angle – a continuous measure taking negative (from –16.26) to positive (to 61.39) values. The higher the angle value is, the more altruistic is the SVO. Apart from continuous measurement, the measure has cutoff scores enabling the participants to be classified into the four most commonly observed SVO types.

Empathy. Empathy was measured using the Polish adaptation of the Empathy Quotient-Short (EQ-Short; Wakabayashi et al., 2006; Polish: Jankowiak-Siuda et al., 2017). It is a self-report, unidimensional, 22-item scale with items such as “I really enjoy caring for other people”; “Other people often say that I am insensitive, though I don’t always see why”. Participants answered on a scale of 1 (definitely not) to 4 (definitely yes). Some items are reverse coded. The authors of the Polish version suggest computing a general score through summarizing given answers. Due to the lack of missing data, such a form of general score computation was employed. The reliability of the scale in the current study was α = .85.

PROCEDURE

The study was questionnaire-based and conducted online in February 2020. The materials and procedure conformed to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki with later amendments and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at The Maria Grzegorzewska University in Warsaw (consent no. 206-2019/2020 issued on February 19, 2020).

The survey was anonymous. The information about the survey was put on social media, in student, city, and local groups across Poland. The study was described as a “Study about decision making and reacting in everyday situations”, and the research question as “whether and how young adults engage in volunteerism, make decisions and perceive themselves”. Participants aged 18-35 were invited to take part, both those who had engaged in volunteerism and those who never had. The participants were not remunerated. Data were saved by the survey system only when a participant filled out the whole questionnaire set without missing data.

During preliminary analyses, it was assessed whether participants fit the inclusion criteria – being aged 18-35 and whether they answered all attention check questions (see Measures section) correctly. Data from 442 participants were complete and saved by the system; however, only 402 people matched the inclusion criteria and were taken into account for the analyses presented below.

IBM SPSS 25.0.0.2 for Windows was used to test the hypotheses. The main hypotheses were tested using regression with bootstrapping (bootstrap samples N = 5000) with the PROCESS 3.2.01 macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). Effect sizes were computed using Psychometrica.de (Lenhard & Lenhard, 2016).

MATERIALS AND DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The study materials and data are openly available in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/fp6n2/).

RESULTS

Regarding SVOs, based on cutoff scores of SVO angle, among non-volunteers, 2 (0.9%) were classified as competitive, 32 (14.3%) as individualistic, 188 (83.9%) as prosocial, and 2 (0.9%) as altruistic. Among volunteers, 18 (10.1%) were classified as individualistic, 157 (88.2%) as prosocial, and 3 (1.7%) as altruistic.

Table 1 presents Pearson’s correlations between continuous variables from the study, descriptive statistics, and results of the test of intergroup differences between non-volunteers and volunteers.

Table 1

Correlations between variables, means, standard deviations in the sample and within groups (non-volunteers and volunteers) and results of test of intergroup differences

Data from Table 1 suggest that in non-volunteers, empathy was positively related to altruistic SVO (r = .18, p < .01), whereas in volunteers it was negatively related to altruistic SVO (r = –.28, p < .001). Non-volunteers and volunteers differed significantly in their empathy (U = 17324.00; p = .024) and SVO (U = 17682.50; p = .049), with volunteers exhibiting higher levels of these traits than non-volunteers. Non-volunteers were also significantly older than volunteers (U = 16767.00; p = .006).

In the subsequent step, a moderation analysis with bootstrapping was performed, predicting altruistic SVO with empathy as an independent variable and participation in volunteerism in the last year as a moderator. Table 2 presents details regarding the model’s validity. Coefficients are given with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

Table 2

Model predicting altruistic social value orientation based on empathy and volunteerism in the previous year

| Variable | B [95% CI] | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathy | .30 | .10 | 2.85 | .005 |

| [.09, .50] | ||||

| Volunteerism | 19.19 | 3.88 | 4.95 | < .001 |

| [11.56, 26.81] | ||||

| Empathy × Volunteerism | –.73 | .16 | –4.51 | < .001 |

| [–1.05, –.41] | ||||

| R2 | .06 | |||

| F(3, 398) | 8.36 | |||

| p | < .001 |

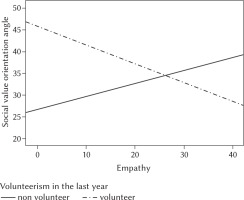

The model was a good fit for the data, F(3, 398) = 8.36, p < .001, accounting for 5.9% of variance in altruistic SVO. Empathy (B = .30, 95% CI [.09, .50]) and volunteerism in the previous year (B = 19.19, 95% CI [11.56, 26.81]) were significant predictors of altruistic SVO. Volunteerism participation in the previous year appeared to be a significant moderator of the relationship between empathy and altruistic SVO (B = –.73, 95% CI [–1.05, –.41]). For non-volunteers, the higher the level of empathy was, the higher was the level of altruistic SVO, whereas for volunteers, the relationship was inversed. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship.

Figure 1

Relationship between empathy and altruistic social value orientation in non-volunteers and volunteers

For exploratory purposes, a correlation analysis between empathy and altruism was also performed separately in the group of participants who never volunteered in their lifetime (N = 84) and who volunteered, but not in the last year (N = 140). In both groups the correlation was not statistically significant (r = .17, p > .05 and r = .15, p > .05, respectively). The Kruskal-Wallis H test also indicated that three groups (people who did not volunteer in their lifetime, volunteers in a lifetime, but not in the last year, and volunteers in the last year) differed significantly in empathy (H(2) = 8.21, p < .05; people who did not volunteer in their lifetime had the lowest empathy and volunteers in the last year had the highest empathy), and in altruistic SVO (H(2) = 10.37, p < .01; people who did not volunteer in their lifetime had the lowest empathy and volunteers in the last year had the highest empathy).

DISCUSSION

The aim of the current study was to explore the potential differences between volunteers in the last year and non-volunteers in the relationships between empathy and altruistic SVO.

First, it should be noted that the majority of both non-volunteers and volunteers were classified as a prosocial SVO type. However, consistent with the previous literature, volunteers were significantly more empathetic and altruistically oriented than non-volunteers. Volunteerism is a form of sustained, helping behavior (Penner, 2002; Wilson, 2000). Continued engagement, which sometimes involves significant emotional workload, is more likely for people who have personality dispositions to do so – for instance, empathy and altruism. This is in line with findings of the importance of role identity in volunteer engagement (Finkelstein et al., 2005; Marta et al., 2014). Believing that volunteerism is congruent with one’s personality, preferences and moral norms enhances engagement in it. Being empathic and altruistic – and therefore understanding other people and being keen to share resources with them – might also boost sustained volunteerism.

Volunteerism participation in the previous year appeared to be a moderator of the relationship between empathy and altruistic SVO. For non-volunteers, the relationship was similar to the well-established assumptions regarding the fostering role of empathy in altruistic behaviors. It corresponds to the empathy-altruism hypothesis, stating that empathy fosters altruistic behaviors (Batson et al., 2015). However, it needs to be noted that when people who did not volunteer in their lifetime and people who volunteered in their lifetime, but not in the last year, were taken separately, the correlation between empathy and altruistic SVO was non-significant. Thus, the positive correlation observed in the joint group of people who did not engage in volunteering in the last year should be treated with caution. Further research on empathy and SVO measured with a decomposed game in the general population is required.

For people who were engaged in volunteerism in the last year, the relationship between empathy and altruism was negative. This is an unexpected result which is worth further exploration. The moderation analysis indicated that the higher the altruistic SVO was, the lower was the empathy of a volunteer. This result may stem from the fact that SVO is measured as an inclination toward dividing money between a person and an imagined “other”. Although volunteerism and sharing are both forms of prosocial behaviors, they are significantly different. Volunteerism implies long-term, personal costs (time, own resources, continuous engagement, and working in person, most often with no significant remuneration), whereas sharing money is a form of instant, instrumental help, and, as measured in a decomposed game, does not require much effort – the participant just has to divide the amount of money. Furthermore, knowing the realities of people or issues to which volunteers devote their time, they might be less keen to share money (instant help). It might stem from a conviction that might be present among volunteers that long-term help can be more fruitful than instant, instrumental sharing (e.g., sharing money, as in the altruistic SVO measure employed in the present study), especially with unknown people. Moreover, the game did not specify the money recipient – it was simply a “stranger”. Given that no information was provided about that, volunteers, who realize their empathy in their work, might have been reluctant to share money. This could be an example of moral licensing – deriving confidence from past moral behavior when violating one’s own moral standards (Merritt et al., 2010). Moral licensing could appear given the order of questionnaires – first, the participants recalled being a volunteer or not and then answered the SVO measure and empathy questionnaire. It is also worth noting that people are more inclined to charitable giving to reduce deficits than to support growth of others (Jasielska et al., 2019). Thus, volunteers in the current study, who reduce deficits by choosing to be a volunteer, might have been reluctant to share (even imagined) money when they did not know whether their help was really needed for someone or only promoted the accumulation of their goods.

It is also possible that for volunteers, a low altruistic tendency is a form of coping with heightened empathy, which is an emotional response. Heightened sensitivity to the emotional distress of others, as well as taking others’ perspective, might be a burden and stressor (Udipi et al., 2008), with which volunteers need to cope. Limiting altruistic behaviors in domains other than volunteerism, for instance, decreased readiness to share financial resources with others, might be a form of such coping. Granting more resources in the SVO measure to oneself while being highly empathic, as was observed among volunteers, might also be a form of displaying a conviction that one deserves a reward for being active in the real-life volunteering context. This is in line with findings regarding the role of narcissism in volunteering. Narcissism might predict engagement in prosocial behaviors, especially those that are publicly visible (Konrath et al., 2016). It was speculated that narcissistic people are sensitive to the vulnerability of other people to take advantage of it, and so they enjoy helping others to become a “hero”. Narcissism is also connected to heightened egoistic (e.g., more career-oriented and less humanitarian) motivations to volunteer (Brunell et al., 2014; Konrath et al., 2016). It is possible that in the current study engagement in volunteering was associated with narcissistic tendencies, which in turn resulted in a negative link between empathy and altruistic SVO; however, studies employing a direct measure of narcissism are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

It should also be noted that volunteerism, regardless of the abovementioned trait of narcissism of the person who engages in it, is not necessarily a purely altruistic action. Numerous researchers note that an interplay of egoistic and altruistic motivations plays a role in volunteerism engagement (Bussell & Forbes, 2002; Hartenian & Lilly, 2009). Therefore, empathy, which enhances the tendency to help others and sustain volunteer activity, might not necessarily be associated with altruistic behaviors in volunteers, whose main motivations are for instance career-related or are a response to social pressure to volunteer (see Brunell et al., 2014).

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

The study has several limitations that should be addressed in further investigations. The study by design focused on a specific age group, acknowledging the importance of developmental period in volunteer engagement (Boling, 2005), but limiting the conclusions to the group of young adults. The volunteers were not analyzed separately according to their volunteer focus, which is a method employed by other researchers in the field (e.g., Maki et al., 2016), and has several strong points (such as capturing more “general” patterns which might be applied to people who are actively performing volunteerism). However, exploring the observed pattern in subgroups of volunteers (e.g., volunteers caring for people, educational volunteers, volunteers working with animals, separately) and including a scale for measuring volunteer motivation would enable a more in-depth exploration of the reasons for a negative association between empathy and altruistic SVO in volunteers.

Furthermore, the used empathy measure does not differentiate between affective and cognitive aspects of empathy, which makes it impossible to investigate the possible differences between patterns of linkages between affective/cognitive empathy and altruistic SVO. The altruistic SVO measure employed in the current study operationalizes altruism as an inclination toward sharing money resources, which is a form of helping that is different from devoting time to others without remuneration, as volunteerism is. Exploring the observed pattern with different operationalizations and interpreting the findings according to the features of used instruments will extend knowledge about the differences between volunteers and non-volunteers in their expression of prosocial personality traits. In light of the results, it is also advisable to continue research on various groups of volunteers, including additional variables, such as narcissism or motivations to volunteer.

The design of the study was cross-sectional, obtained from a single study, making it impossible to interpret the findings as determinants or results of volunteer engagement, and serving as an exploratory and pilot study for further investigations. The data are derived from Caucasian participants from a developed, European country. Exploring the patterns of relationships between empathy and altruism in different cultures would be of value in future research. Moreover, the study was conducted online, but data gathered from randomly selected groups on social media cannot be considered representative for the whole population of young Polish adults. Furthermore, women greatly predominated within the sample, which makes it impossible to identify potential gender differences in the investigated constructs among non-volunteers and volunteers.