BACKGROUND

Contemporary adolescents, also known as Generation Z (National Chamber Foundation, 2012), are an important group of consumers due to the role they play in today’s economy. The latest marketing reports (GfK, 2018) indicate that they spend more money, and exert a bigger influence on the choice of many products and services for the entire household. The materialistic lifestyle seems to be an integral part of modern life for teenage consumers (Twenge & Kasser, 2013). Unfortunately, greater materialism among teenagers is also associated with addiction to new technology (Gentina & Rowe, 2020), compulsive buying (Islam et al., 2017), emotion dysregulation (Estévez et al., 2020), and depression (Mueller et al., 2011). In adolescence, building one’s own identity is the most important developmental task (Erikson, 1968) and, for young consumers, material goods serve as a source of power by helping them to build their position within their peer group (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008), as self-image communicators, as a way to compensate for the deficiencies of self-image (Chaplin & John, 2007; Chaplin et al., 2014; Wicklund & Gollwitzer, 1981), and for the protection of one’s image (Munichor & Steinhart, 2016).

Although most studies treat adolescents as a homogeneous group, research on age differences in the materialistic behavior of adolescents indicates there is an age effect during this period in their lives (Gentina & Rowe, 2020). Research has shown differences regarding the use of and attitudes towards material goods as they may be related to self-esteem, which change during adolescence (Chaplin & John, 2007, 2010; Zawadzka & Lewandowska-Walter, 2016). Furthermore, younger adolescents have higher levels of social conformity to norms and need more social support compared to late adolescents (Berndt, 1979). Therefore, we are interested to ascertain whether adolescents differ in their consumption habits depending on the stage of their development.

Notwithstanding the above observations, much of the research indicates a dependence between materialism and the role of material goods in building the concept of oneself (Lee et al., 2020; Razmus et al., 2020); however, little is known about this among adolescents. Therefore, we applied the moderated mediation model to investigate this association and the underlying mechanisms between materialism and BESC among Generation Z students.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

FROM MATERIALISM TO BRAND ENGAGEMENT

The prevailing literature on marketing points to the huge role played by materialism in consumer decisions (Goldsmith et al., 2012). While materialism has been intensively debated since the 1990s (Sabah, 2017), its role in the lives of adolescents has seldom been studied (e.g. Chaplin & John, 2007, 2010; Gentina & Rowe, 2020; Zawadzka & Iwanowska, 2016; Zawadzka et al., 2018).

Materialism is defined from several different perspectives. The two main approaches to interpreting materialism see it either as a personality trait, i.e., the importance a person attaches to their possessions (Belk, 1984), or as a value system in which possession is at the center of everything (Richins & Dawson, 1992). Shrum expands these concepts and argues that it helps consumers to shape and maintain their identity (Shrum et al., 2014).

Materialism among adolescents includes the need to buy things, the enjoyment of possessions, and the desire to acquire and secure money for purchases (Goldberg et al., 2003). Previous studies on teenagers have shown that materialism contributes to excessive consumption and impulsive purchases, and is a predictor of compulsive buying behavior (Islam et al., 2017). Research also shows that adolescents rejected by their peers demonstrate a higher level of materialism than peers who are accepted in the group (Jiang et al., 2015), and that adolescents whose self-concept is particularly unstable are especially prone to sourcing and consuming items to impress others (Chaplin & John, 2007).

The modern term corresponding to materialism is brand engagement in self-concept (BESC). Materialism is a broader global construct and means assigning excessive importance to the possession of material goods (Belk, 1984; Flynn et al., 2016; Richins & Dawson, 1992). In turn, according to Sprott et al. (2009), BESC is a consumer’s tendency to differentiate themselves by integrating a brand with their self-concept. This global disposition is an important individual variable that characterizes consumers. The BESC shows consumers along a continuum from the lowest end, where brands are unimportant to their sense of self, to the highest end, where they identify strongly with brands.

The concept of BESC, also important for researchers and practitioners (Razmus et al., 2017), constitutes a niche area in the broader context of brand (Ismail et al., 2021).

The evidence contained in the literature is scarce regarding the relationship between brand engagement and specific marketplace behaviors (Flynn et al., 2016); however, studies show a significant positive correlation between BESC and attitudes toward shopping among genders (Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2012). Taking certain brands into account in one’s own self-concept is, therefore, a consequence of the desire to build and maintain an appropriate image (Razmus et al., 2017). Thus, we can formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: Materialism is positively correlated with BESC.

FROM MATERIALISM TO CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION

Like materialism, conspicuous consumption (CC) refers to a behavior in which an individual shows wealth by purchasing and consuming luxury goods (Trigg, 2001). CC is also often defined as the tendency of consumers to show their social status and self-image through the visually observable products they consume (Chipp et al., 2011). Therefore, the basic motivation to purchase visible goods is prestige (Belk, 1988; Wu et al., 2017), and it follows that the satisfaction with the product often results from the reaction of recipients and not from the actual use of the product (Shao et al., 2019). There are relatively few studies that set out to analyze the relationship between psychological factors and attitudes towards conspicuous consumption during adolescence (Velov et al., 2014). Studies have identified materialism and CC as being related but also as different theoretical constructs (Podoshen et al., 2011). The accumulation of material goods is the essence of materialism, whereas demonstration of one’s possessions is the defining element of consumption (Velov et al., 2014). Conspicuous consumption is especially attractive to materialists interested in the symbolic meaning of products (Richins, 1994) and materialistic values have a significant impact on CC orientation (Podoshen et al., 2011).

Several studies have linked materialism to symbolic consumption (Prendergast & Wong, 2003), as well as CC (Segal & Podoshen, 2013), suggesting that highly materialist consumers tend to buy expensive products more ostentatiously than low-materialist consumers (Wu et al., 2017). The association between materialism and CC is also confirmed by the results of research on luxury goods (Chan et al., 2015). Furthermore, as it is well known that teenagers closely follow their peers, it is very likely that they pay attention to the way they are perceived by others (Brown & Lohr, 1987). For young people, the acquisition of expensive goods and services is often used as a tool for gaining social recognition (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008).

Some researchers explicitly posit materialism as an antecedent of the level of a brand’s integration into consumers’ self-concept (Rindfleisch et al., 2009). Thus, conspicuous consumption, as a more specific behavioral pattern than materialism, may be at least partially a consequence of this materialism.

Therefore, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H2: Materialism is positively associated with conspicuous consumption.

FROM CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION TO BESC

Research indicates that one of the factors mediating between materialism and BESC might be so-called status consumption or conspicuous consumption (Flynn et al., 2016; Rehman et al., 2019). In terms of meaning, status consumption and conspicuous consumption are similar phenomena (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004); therefore, the relationship between conspicuous consumption and BESC can be understood as analogous with the relationship between status consumption and BESC.

The inclination to consume for prestige stems in part from materialism (Kasser, 2002; Lertwannawit & Mandhachitara, 2012), and results in other market behaviors such as using brands to build self-concept and the social self. Brands can represent attributes important to a particular group, and their purchase stems from the desire to achieve a desired image within a certain reference group (Goldsmith et al., 2012). The relation between status consumption and BESC is, therefore, positive (Goldsmith et al., 2012).

However, conspicuous consumption and BESC differ conceptually and evolve from very different motivations. In the case of BESC, the consumer uses branded goods to enhance the perception of themselves and to create their own image, whereby brands do not have to be prestigious. Conspicuous consumption, on the other hand, refers to the image that people present to others. Previous studies suggest that status consumption mediates the relationship between materialism and BESC in adults (Flynn et al., 2016; Rehman et al., 2019), and we can therefore expect CC, although different from status consumption, to be linked to materialism and BESC. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3: Conspicuous consumption has a positive impact on BESC and mediates the relationship between materialism and BESC.

THE ROLE OF TEENAGERS’ AGE

One of the most important developmental tasks for adolescents is shaping their own identity, so it can be expected that young consumers who want to develop their self-esteem will become more involved with brands (Hsiech & Chang, 2016), because when adolescents choose certain brands they try to express their identity (Autio et al., 2016). Brands help to develop the self-concept in young consumers and social groups (Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer, 2013). Experimentally, Goldsmith et al. (2012) and Flynn et al. (2011) found that BESC levels are higher in adolescents than in adults. Chaplin and John (2005) found that the importance of brand association increases with age, along with an increase in the depth of connections. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H4: Age is associated with BESC.

The effect of age at different stages of adolescence is not well known (Hong et al., 2019). Understanding the importance of tangible goods for self-concept emerges around the same time as teenagers experience decline self-esteem (ages 12-13; Chaplin et al., 2014; Robins et al., 2002). In late adolescence (ages 15-18), material possessions play a lesser role which is associated with improved self-esteem (Chaplin et al., 2014; Zawadzka & Lewandowska-Walter, 2016) and a more realistic self-concept, so adolescents no longer need to use as many coping strategies as possible (McCarthy & Hoge, 1982). Their repertoire of strategies to enhance self-esteem and manage the experiences they communicate to others is also bigger (Chaplin & John, 2007; McCarthy & Hoge, 1982). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H5: Age negatively moderates the relationship between CC and BESC.

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

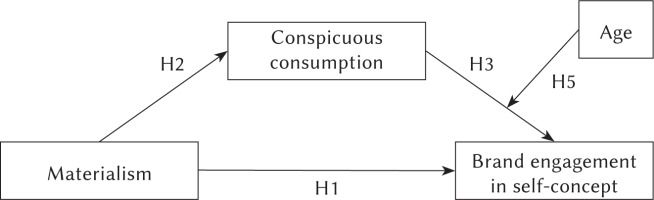

Hypotheses formulated from the cited research literature on materialism indicate that higher adolescent materialism leads to higher conspicuous consumption of products and brands. We propose a moderated mediation model, where conspicuous consumption partially mediates the relationship between materialism and BESC, with age moderating the relationship between conspicuous consumption and BESC (Figure 1).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study group consisted of 581 students aged 13 to 17 (M = 15 years, SD = 1.42), 51.6% of whom were girls. As many as 75.4% of the students received pocket money (Me = PLN 200). 2.6% of teenagers described the financial status of the family as poor, 67.6% as middle-class, 28.2% as wealthy and 1.6% as very wealthy. The examined sample enables the identification of correlations in the population of at least r = .10 with a probability of 1 – β = 0.80 (one-tailed test).

PROCEDURE

The first step was to obtain ethical approval from the ethics committee at the appropriate university. We also contacted the schools to obtain consent for data collection. All students whose parents consented to the study and who themselves agreed to participate were included in the study.

The data were collected through individual interviews. Before responding, the respondents were trained by the researcher to use the Likert scale. The scale was printed separately in A4 format, and the subject had it in front of them during the examination. The study was conducted without financial gratification and participants were assured of anonymity.

Out of 5 product categories, the interviewer chose one category that was familiar to the respondent (see Table 1). The respondent was then given the names of the brands in the selected category on individual cards, from which he or she initially chose the ones he or she knew. The researcher then selected the brand for the study. The researcher’s choice was dependent on previous surveys, i.e., brands were chosen that were less frequently selected by previous respondents. This procedure ensured that an even number of respondents per brand was maintained.

Table 1

Categories and brands considered by respondents (%)

In the next stage, a vivid image of one of the selected brands was induced. The respondent’s task in this stage was to imagine a typical user of the brand in question, after being instructed to do so.

The survey started with the Youth Materialism Scale (YMS), Conspicuous Consumption Scale, and the BESC Scale. Next, participants answered questions about socio-demographic data.

MEASURES

Materialism. We measured teenagers’ materialism using the 10-item YMS scale from Goldberg et al. (2003), Polish adaptation (Zawadzka & Lewandowska-Walter, 2016). The scale measures materialism, defined as the desire to purchase products and brands, the desire to have goods and money to purchase them, and to have a job that provides the ability to purchase. The reliability of the scale in the present study sample was α = .81

Conspicuous consumption. To measure conspicuous consumption, we used the scale of Souiden et al. (2011), self-translation, which consists of five items (e.g. “I purchase branded accessories because they make me gain respect”). Cronbach’s α reliability in this study was α = .92.

Brand engagement in self-concept. BESC (Sprott et al., 2009) was measured with the Polish version of the scale (Razmus, 2012), which includes 4 items in its shortened version. Cronbach’s α reliability of the scale was α = .87.

MODEL ESTIMATION

A moderated mediation model (Figure 1) was tested by using the Hayes (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 14) with the mean composite scores on the items for materialism, CC, and BESC. The analysis assessed (1) the effects of materialism on BESC, (2) the effects of materialism on CC and (3) the effect of CC on BESC (as moderated by age). The 95% bias-corrected confidence interval from 5000 resamples was generated by the bias-corrected bootstrapping method to evaluate the statistical significance of the correlation and effects.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

The descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables materialism, conspicuous consumption and BESC are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s r correlations

Inspection of the correlations shows that materialism is positively correlated with conspicuous consumption (boot 95% CI = [0.56, 0.67]) and positively correlated with BESC (boot 95% CI = [0.31, 0.47]). The correlation findings also reveal that conspicuous consumption is significantly correlated with brand engagement in self-concept (boot 95% CI = [0.46, 0.60]). In addition, age was negatively related only to conspicuous consumption (boot 95% CI = [–0.17, –0.01]).

MODERATED MEDIATION

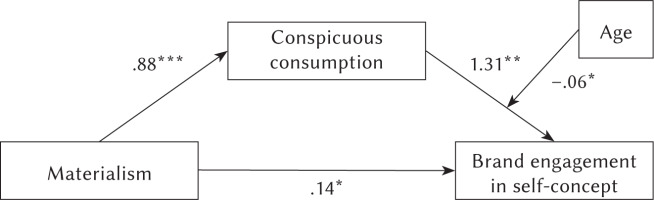

The next step was mediation and moderation analysis. The results (Figure 2) showed that materialism positively predicted conspicuous consumption (95% CI = [0.79, 0.97]) as well as BESC (95% CI = [0.02, 0.26]). Conspicuous consumption (95% CI = [0.58, 2.04]) and age positively predicted brand engagement in self-concept (95% CI = [0.01, 0.35]). The interaction of conspicuous consumption and age negatively predicted brand engagement in self-concept (95% CI = [−0.10, −0.01]), indicating that age significantly moderated the mediating effect of conspicuous consumption. In Figure 2, the results of the PROCESS macro are illustrated.

Figure 2

Moderated mediation model

Note. N = 581. Unstandardized coefficients are presented. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

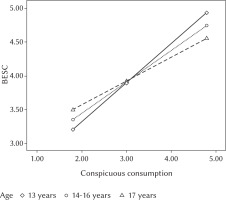

Figure 3 presents the BESC as a function of conspicuous consumption in different age groups. Conditional indirect effect analysis revealed that the indirect effect was more significant for early adolescents (13 years), effect = 0.51, bootSE = 0.07, boot 95% CI = [0.36, 0.66], than for those in middle adolescence (14-16 years), effect = 0.41, bootSE = 0.05, boot 95% CI = [0.31, 0.51] and late adolescence (17 years), effect = 0.31, bootSE = 0.06, boot 95% CI = [0.19, 0.43]. This means that conspicuous consumption mediates the relationship between materialism and BESC in each age group of teenagers, and the power of mediation declines with age.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to investigate the relationship between materialism and adolescents’ brand engagement in self-concept and to identify the potential mechanism of the way in which materialism would predict BESC. As expected, the results demonstrated a positive correlation between materialism and BESC, the mediating effect of CC, and the moderating effect of age.

THE CORRELATION BETWEEN MATERIALISM AND BESC

The results indicated that materialism positively predicted adolescent BESC, which was consistent with previous research within the adult consumer group (Flynn et al., 2016; Goldsmith et al., 2012). Our study shows that the more materialistic teenagers are, the more likely it is that they will construct themselves through brands. Choosing or using specific brands can be interpreted as shaping identity (Autio et al., 2016). Young people are looking for a way to build their identity, and brands can play a large part in this (Sirchuk, 2012).

THE MEDIATING ROLE OF CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION

The finding that materialism predicted adolescent BESC through the mediating effect of CC was consistent with Kasser’s (2002) conceptualization of materialism, defined as a desire for goods and attributes ensuring status. However, the search for status is only one dimension of materialism (Belk, 1988). Brands have symbolic meaning and can be used to build one’s image within a group (Goldsmith et al., 2012). Thus, consumers’ signs of status may be explained, among other things, by valuing materialistic behavior (Flynn et al., 2016). The propensity for conspicuous consumption is partly driven by materialism (Lertwannawit & Mandhachitara, 2012) and subsequently drives other market behaviors, including brand engagement.

THE MODERATING ROLE OF AGE

The results illustrated that age moderated the relationship between conspicuous consumption and BESC, which confirms the assumption that adolescents, depending on their development stage, have different approaches to their materialistic behavior (Gentina & Rowe, 2020). Specifically, for early adolescents, the mediating role of conspicuous consumption was stronger than for middle and late adolescents. These results confirm certain tendencies in teenagers’ materialistic behavior. In late childhood and early adolescence (12-13 years of age), the level of materialism increases along with a decrease in self-esteem. At this stage teenagers develop market knowledge, concepts and ideas related to brands (John, 1999), and these changes are accompanied by consumption. Adolescents also acquire certain goods to belong to a specific social group (Auty & Elliott, 2001). In addition, social belonging, the need for peer support, and higher conformity to social norms are characteristic of younger adolescents (Berndt, 1979). They use material goods to shape their identity and gain prestige (Belk, 1988) as well as to fulfill needs in terms of individualization and social interaction, personalization and group membership (Chan et al., 2013). Teenagers use brands to create their image by purchasing the brands used by their peer groups to gain their approval (Auty & Elliott, 2001).

On the other hand, research has shown that in the period of late adolescence (16-18 years of age), the level of conspicuous consumption decreases, which is associated with a lower need for brand engagement in self-concept. During this time, older adolescents gain greater personal autonomy, become more realistic as regards their own conceptions, and feel better in the social setting, so they need fewer management strategies to overcome low self-esteem (McCarthy & Hoge, 1982).

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The present research is not without certain limitations. First, the research is based on materialism patterns in Polish adolescents, which limits the cultural generalizability of the results. The second limitation is its cross-sectionality, which does not allow conclusions to be established on cause-and-effect relationships. In the future, a longitudinal study would be required to assess the mutual influence of the variables analyzed in the study.

The results indicate that adolescents who are high on the materialism scale build their self-image through the brands whose products they consume. Future research should compare these results with the results of an analogous analysis of older consumers, e.g., in early adulthood. Moreover, future research could analyze how brand image influences the creation of self-concept, i.e., which characteristics are desirable, and which are undesirable for teenagers.

IMPLICATIONS

Answering the question as to what makes young people use brands to shape their self-concept is intriguing, but also important for a wider audience – parents, teachers, therapists, scholars, and market researchers. The results of the research indicate that materialism and ostentatious consumption may be related to building one’s self through brands, which is particularly evident in younger adolescents, and may be related to a drop in self-esteem at this stage of life (Chaplin & John, 2007).

The study was designed to show general trends among teenagers, and so it was conducted in the context of 5 product categories and 50 brands. The use of different categories of products consumed in public allows for a wider range of generalizations of the findings. For these categories, we see that younger teenagers who are oriented towards ostentatious consumption are also more materialistic, which leads them to construct themselves through brands. So, brands that emphasize prestige and position themselves as more luxurious may reinforce these effects, which in turn may lead to greater consumption of these brands.

From a psychological point of view, it is important to support and build among adolescents various strategies to meet their own needs and build self-concept in order to reduce the risk of over-attachment to material goods and the consolidation of this tendency as a way to build self-esteem. Being aware that materialism is linked to the construction of self through brands can highlight the importance of helping teenagers to also develop their identity based on other values and deeper, more interpersonal relationships.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its limitations, the study is an essential step in uncovering the mechanism of BESC by pointing out that materialism could positively predict adolescent brand engagement in self-concept directly and indirectly through conspicuous consumption. Age acts as a moderator and the mediating effect of CC between materialism and adolescents’ BESC is stronger in the case of younger adolescents.