BACKGROUND

From the moment of our birth, we are confronted with numerous problems, big and small, throughout the course of our lives. How we respond to life crises can be shaped by both our genetic characteristics and environmental factors. In particular, the family environment influences our earliest life memories, our perception of problems, and our coping mechanisms (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). Although challenges are common throughout life, this study specifically focuses on the period of emerging adulthood (Buhl & Lanz, 2007), which is considered an intense and stressful period, especially in terms of taking on responsibilities and making decisions regarding adult life. The main reason for this situation is that young adults strive to form an independent identity during adolescence and when they move to higher education they have to make vital decisions and often have to solve daily problems on their own. Additionally, they are faced with many painful decisions and troublesome processes that will affect their future lives, such as making the right career choice, getting a job related to the profession they have chosen, creating autonomous living conditions independent of their parents upon graduation, and choosing a spouse. Distress tolerance is thought to play an important role in fulfilling all these and similar requirements.

Distress is a concept that encompasses all emotional states and indicates whether they can be controlled (Brown et al., 2005). Distress tolerance is defined as the capacity to evaluate, experience, and persevere through negative psychological situations (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Distress can occur as a result of cognitive or physical processes but is experienced as an emotional state. Distress tolerance is among the findings of many psychological conditions such as personality disorders, anxiety, depression, alcohol and substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder, relationship disorders, and suicide, and it emerges as a key concept that is aimed to be increased in all psychotherapy theories (Beck et al., 1988; Hayes et al., 2004). Four characteristics have been defined in relation to distress tolerance (Simons & Gaher, 2005): 1) individuals with a low threshold for tolerating distress describe distress as unbearable; 2) the individual’s lack of acceptance of distress, feeling ashamed of being distressed, and seeing his/her own coping skills as inferior to those of others when evaluating being distressed; 3) the individual’s quick and excessive efforts to avoid negative emotions; and 4) if it is not possible to avoid these negative emotions, in the presence of distressing emotions, all attention is directed to them, and functionality decreases significantly. The commonality of these four characteristics of distress tolerance is how the individual perceives distress emotionally and cognitively and how she/he reacts accordingly. The evaluation of a situation as distress and the perception of the severity of the distress are shaped by personal experiences.

The impact of previous experiences, especially childhood experiences, on individuals’ self-perception and interpretation of events and the world is an area addressed in almost all psychological theories. The psychoanalytic approach emphasises that the three basic areas of individual and social development – love, trust, coping with negative emotions and positive evaluation of sexuality – are determined in the first six years of life and that later adulthood is built on these foundations (Corey, 2008). The psycho-social development theory, which is based on Freud’s theory, explains individuals’ perceptions of themselves as beings worth loving, their confidence in themselves and the world they live in, their sense of autonomy and initiative, and their ability to perceive themselves as strong enough to cope with the problems they encounter in their personality development through childhood experiences. In this regard, attachment theory offers a broad perspective on the impact of childhood experiences on an individual’s adult life. According to this theory, the quality of the relationship established with the caregiver creates internal working models of the world, life, and the individual himself/herself. Childhood is considered a critical period in which these schemas are affected by experiences (Bowlby, 1985). Individuals who have peaceful and happy experiences, who are supported in infancy and childhood, and whose emotional and psychological needs are met, learn that they are valuable, that they can trust people, and that they can love and be loved.

Considering that individual differences affecting developmental outcomes result from the interaction of genes and environmental factors, it is a fact that individuals may react differently to the same behaviours of others related to childhood memories. Therefore, the distinction is how that behaviour is interpreted by the individual, not how people behave in the face of a problem. The quality of the relationship that families establish with their children, how they make the child feel, how the family solves their own problems, and their ability to approach problems are also internalized by the child (Bandura, 1988; Tahiroğlu et al., 2009). Internal working models have a determining effect on what kind of information individuals will direct their attention to, how they will interpret events in the world, and what they will remember and forget (Hayes et al., 2004). If internalizations are healthy, the person learns that life difficulties are surmountable and external obstacles can be overcome, shaping their ability to cope with distressing situations (Epstein & Meier, 1989). In short, it can be stated that our ability to make sense of and cope with the problems we face in adulthood is a result of our sense of self internalised in childhood and our emotional and cognitive inferences about the world we live in.

The first memories of childhood are processed as emotional information since the cognitive structure has not yet matured and shapes the individual’s belief patterns about both themselves and the world (Çalışır, 2009). Over the following years, the influence of these beliefs persists and has an impact on the person’s ability to make sense of and react to distressing situations (Brown et al., 2005). The ability to process emotion-related stimuli in the formation and use of thoughts and behaviours is explained by the concept of emotional intelligence (Mayer et al., 2004, 2008). Today, many studies on this subject have proven that the neural mechanisms underlying social and emotional information processing are interconnected and that the entire brain system is affected by emotions (Hajcak et al., 2009). Therefore, it would not be wrong to say that our emotions and thoughts are intertwined in our behaviour of perceiving the events we experience as distress or coping with them.

Emotional intelligence is the ability to appraise one’s own and others’ emotions, to discriminate among them, to control these emotions by regulating them, and to cope with problems effectively (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). This study was based on the four-dimensional model of Mayer and Salovey (1997). The purpose of using this model is to examine the moderating role of emotional intelligence dimensions (appraisal of own emotions, appraisal of others’ emotions, regulation of own emotions, and regulation of others’ emotions) in the effect of childhood memories of happiness and peace on distress tolerance. The reason for this is that it is very difficult to distinguish Salovey and Mayer’s dimensions of emotional intelligence from each other (Pekaar et al., 2018). Although it is difficult to distinguish between the dimensions, a person’s self-oriented emotional intelligence plays a more effective role in individual mental-physical health (Martins et al., 2010), while competencies in the dimensions of appraising and regulating the emotions of others play a greater role in interpersonal problems and social events (Joseph & Newman, 2010; Kobylarczyk & Ogińska-Bulik, 2018). For example, when faced with an interpersonal problem, the individual must appraise the emotion generated by the event, be able to distinguish their senses, and regulate their emotions, while in the attempt to find a correct solution to the problem, the ability to correctly appraise the other person’s emotions and influence the other person’s emotions will come into play. This study aimed to determine the relationship between childhood peace memories, emotional intelligence, and distress tolerance, which play a key role in coping with life difficulties, as well as the mediating role of the four dimensions (appraising own emotions, appraising others’ emotions, regulating own emotions, and regulating others’ emotions) of emotional intelligence in this relationship. By determining the mediating role of the dimensions, a clear distinction can be made regarding the emotional processes that play a mediating role in the relationship between variables. The results obtained in this study will serve as a source for new research and preventive and interventional studies.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The research group consists of individuals who are in emerging adulthood and continuing their higher education. The purposive sampling method was used to determine the study group. The aim of using this method is to obtain qualified data suitable for the purpose of the study. Accordingly, the research sample consisted of students who attended undergraduate and associate degree programmes at Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, located in the south of Turkey, who continued their higher education outside their home province, were unemployed, economically reliant on their families, and were single. The study involved 570 student participants, and after eliminating incomplete and invalid data, 538 valid surveys were analysed. The research group consisted of 426 female students (79.2%) and 112 male students (20.8%) aged between 19 and 27 years. 251 (46.7%) of the participants were enrolled in associate degree programmes and 287 (53.3%) were enrolled in undergraduate programmes.

MEASURES

Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness Scale (EMWSS). The EMWSS was developed by Richter et al. (2009) to evaluate individuals’ perceptions of their positive childhood memories. Turkish adaptation and validity and reliability studies of the scale were conducted by Akın et al. (2013). The EMWSS is a one-dimensional, 5-point Likert type scale consisting of 20 questions. The scale allows for scores between 20 and 100 with no reverse coded items. Increasing scores signify elevated levels of happiness and peaceful childhood memories. The internal consistency reliability coefficient of the scale is .93. (Akın et al., 2013). The high reliability coefficient of the Turkish form of the EMWSS indicates that the reliability is at a sufficient level.

Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS). Developed by Simons and Gaher (2005), the Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) is a 5-point Likert-type scale consisting of 15 items to measure individual differences in the capacity to endure distress. The Turkish adaptation of the scale and validity-reliability analyses were conducted by Sargın et al. (2012). While the original scale consists of four dimensions, the Turkish version consists of a total of three dimensions: tolerance, regulation, and self-efficacy. The scale’s internal consistency coefficients were .90 for the tolerance dimension, .80 for regulation, and .64 for the self-efficacy dimension. The overall score from the scale was used in this study, and the internal consistency reliability coefficient for the total score of the scale was .89.

Rotterdam Emotional Intelligence Scale (REIS). The scale developed by Pekaar et al. (2018) was adapted to Turkish by Tanrıöğen and Türker (2019). This 28-item, 5-point Likert type scale consists of the dimensions of appraising one’s own emotions, appraising others’ emotions, regulating one’s own emotions, and regulating the emotions of others. The internal consistency reliability coefficients of the scale were .91 for the dimension of appraising one’s own emotions, .91 for appraising the emotions of others, .89 for regulating one’s own emotions, .93 for the dimension of regulating others’ emotions, and .94 for the overall scale.

DATA COLLECTION

In the data collection process, the personal information form, the Emotional Intelligence Scale, Distress Tolerance Scale, and Early Memories of Warmth and Safeness Scale prepared via Google Forms were distributed electronically to the students who volunteered to participate in the study through their counsellors. Information and consent forms about the study were presented to the students electronically.

DATA ANALYSIS

To begin with, descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients and correlation analyses were completed using SPSS 26. Afterwards, a multiple mediation model was analysed to test the hypothesis that emotional intelligence dimensions (self-focused emotion appraisal, other-focused emotion appraisal, self-focused emotion regulation, and other-focused emotion regulation) act as multiple CIPP-00836-2023-01 mediators between early warmth and safeness memories and distress tolerance. PROCESS Model 4 was used to test the hypothesised multiple mediation model with 5,000 bootstrap samples. Early memories of warmth and safeness (X), the dimension of emotional intelligence (M), and distress tolerance (Y) were entered into Model 4 (Hayes, 2018).

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Distress tolerance was positively correlated with early memories of warmth and safeness (r = .23, p < .001), other-focused emotion appraisal (r = .18, p < .001), self-focused emotion regulation (r = .21, p < .001), and other-focused emotion regulation (r = .16, p < .001). Moreover, early memories of warmth and safeness was positively correlated with self-focused emotion appraisal (r = .29, p < .001), other-focused emotion appraisal (r = .15, p < .001), self-focused emotion regulation (r = .24, p < .001), and other-focused emotion regulation (r = .20, p < .001). On the other hand, distress tolerance was not significantly associated with self-focused emotion appraisal (r = .08, p > .05). Descriptive statistics, correlations, and Cronbach’s α values are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and reliabilities for the study variables

MULTIPLE MEDIATION ANALYSES

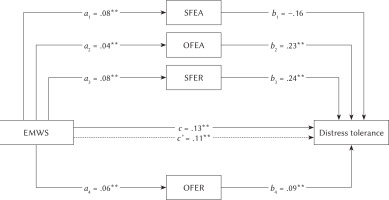

Applying PROCESS model 4, we tested whether the dimensions of emotional intelligence mediate the relationship between early memories of warmth and safeness and distress tolerance (see Table 2 and Figure 1). The results indicated a significant total effect (path c; without mediator) of early memories of warmth and safeness on distress tolerance (β = .13, t(538) = 5.42, p = .001, 95% CI [.08; .17]), significant direct effect (path c′; with mediator) (β = .11, t(538) = 4.34, p = .001, 95% CI [.06; .16]).

Table 2

Path coefficients of the model

Figure 1

The multiple mediation model

Note. **p < .001; EMWS – early memories of warmth and safeness; SFEA – self-focused emotion appraisal; OFEA – other-focused emotion appraisal; SFER – self-focused emotion regulation; OFER – other-focused emotion regulation.

The results also revealed that early memories of warmth and safeness was associated with higher other-focused emotion appraisal scores (path a2; β = .04, p = .001) and self-focused emotion regulation (path a3; β = .08, p = .001) and these, in turn, were positively associated with distress tolerance (path b2, b3; β = .23, β = .24, p < .05, respectively). Lastly, early memories of warmth and safeness did not have any significant indirect effects through self-focused emotion appraisal (β = –.01, 95% CI [–.03; .00) and other-focused emotion regulation (β = .01, 95% CI [–.01; .02) on distress tolerance.

DISCUSSION

The results of the study revealed a statistically significant and positive relationship between the independent variable of childhood memories of warmth and safeness, and the dependent variable of distress tolerance total score. In other words, the distress tolerance and emotional intelligence (in all dimensions) of individuals in emerging adulthood who perceive their childhood as peaceful and happy are significantly higher than those of individuals who did not feel happy and peaceful in their childhood. Although the examination of the literature did not reveal any studies examining the relationship between childhood memories of warmth and safeness and distress tolerance and/or emotional intelligence, several studies focusing on understanding the relationship between childhood maltreatment and/or traumatic experiences and distress tolerance were found. For example, Berenz et al. (2018) examined the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and distress tolerance in their study and concluded that increased negative childhood experiences result in decreased distress tolerance. In another study with a similar sample, the relationship between childhood maltreatment and various mental problems (PTSD, depression, anxiety, and alcohol use) and the mediating role of distress tolerance (DT) in this relationship were examined, and the results of the study showed a positive relationship between the reporting rate of childhood maltreatment and mental problems, while DT was found to have a high mediator effect, and that the increase in DT was effective in reducing the incidence of mental problems (Robinson et al., 2021). Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between childhood traumatic experiences and various psychopathological disorders (post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and suicidal tendencies and behaviours) and DT (Rette et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2021). Although all the findings from this study indicate a positive relationship between childhood maltreatment and all mental disorders discussed, the relationship between distress tolerance and childhood maltreatment was negative and significant, aligning with the finding of a positive and significant relationship between high scores in childhood peaceful memories and DT. Individuals who have their needs for love, belonging, and trust fulfilled in childhood and experience a happy and peaceful childhood are better able to tolerate challenging situations in adulthood with greater ease and health. Based on this finding, it can be concluded that the experiences internalized during childhood are a strong predictor of the ability to be resilient in the face of troublesome situations encountered in the emerging adult period.

The second important finding obtained in the study is the significant and positive relationship between childhood memories of warmth and safeness and all dimensions of emotional intelligence (self-focused emotion appraisal, other-focused emotion appraisal, self-focused emotion regulation, and other-focused emotion regulation). Upon examination of the literature, it was found that although there have been no studies that examined the relationship between feeling happy and peaceful in childhood and emotional intelligence, many studies have examined the effects of childhood maltreatment and childhood traumatic experiences on emotional intelligence. For example, Schwartz (2016) examined the relationship between emotional intelligence scores of negative childhood experiences and social-cognitive deficiencies and found that emotional intelligence scores decrease in connection with the frequency and severity of emotional traumatic experiences and domestic maltreatment experiences in childhood and that deficiencies in social-cognitive functions are positively related. When other studies in this field were examined, it was found that individuals who experienced maltreatment in childhood had deficiencies in the ability to recognize the emotions of others (Pajer et al., 2010; Shenk et al., 2013). Brain imaging studies examining the impact of childhood maltreatment on brain regions involved in adult social interaction and its neurological effects on emotion recognition and general intelligence development have found that individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment show atypical neural responses to emotional facial expressions and a reduction in the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory (Taylor et al., 2006). These data are consistent with the finding of a significant and positive relationship with all dimensions of emotional intelligence, which has a positive effect on human relations and the mental health of individuals who perceive childhood as peaceful and happy.

When the relationship between distress tolerance and emotional intelligence dimensions was examined, it was found that the relationship was positive and significant with all dimensions (self-focused emotion regulation, other-focused emotion appraisal, and other-focused emotion regulation), except for self-focused emotion appraisal. Although there is no study in the literature investigating the relationship between distress tolerance and emotional intelligence dimensions to the best of our knowledge, one study was found addressing the relationship between emotional intelligence dimensions and subjective stress, as emotional intelligence can be considered a social skill that controls stress and affects a person’s ability to cope with demands and environmental pressures. This study examined the relationship between subjective stress reactions, task performances, and emotional intelligence dimensions, and the results revealed a significant negative relationship between subjective stress and the self-focused emotion appraisal dimension of emotional intelligence, which is consistent with the results of our study (Pekaar et al., 2019). However, in the same study, a significant negative relationship was found between subjective stress and self-focused emotion appraisal of emotional intelligence, which is different from our study (Pekaar et al., 2019). In the literature, self-focused emotion appraisal is defined as paying attention to one’s emotion and understanding it accurately without changing the effect of the emotion. The reason for not finding any relationship between distress tolerance and self-focused emotional appraisal in this study may be that the sample group was evaluated in terms of distress tolerance scores, not stress or a problem situation.

When the multiple mediation model was tested, it was found that childhood memories of happiness and peace have a direct, highly positive effect on the distress tolerance of individuals in emerging adulthood. Moreover, it was concluded that while self-focused emotion regulation and other-focused emotion appraisal dimensions of emotional intelligence played a significant positive mediating role in this effect, self-focused emotion appraisal and other-focused emotion regulation did not play any mediating role. When the literature was examined, no study testing the mediating effect of the emotional intelligence dimensions (self-focused emotion appraisal, self-focused emotion regulation, other-focused emotion appraisal, and other-focused emotion regulation) in the concepts addressed in this study was found. The results showed that the self-focused emotion regulation and other-focused emotion appraisal sub-dimensions of emotional intelligence have a high-level mediating role in the relationship between childhood memories of happiness and peace and distress tolerance. This finding is parallel to the finding that negative experiences in childhood have a negative effect on psychological resilience, as demonstrated in various studies (Cyniak-Cieciura, 2021). We believe that the study results will contribute to new research in terms of understanding which emotional intelligence dimension specifically has a high-level mediating role in the relationship between childhood memories of happiness and peace and DT and understanding the working mechanisms underlying emotional intelligence.

LIMITATIONS

The fact that this study covers young adults between the ages of 19 and 27 and that the sample consists mostly of women may limit the generalisability of the findings in terms of demographic homogeneity. The cross-sectional design of the study conducted with university students in emerging adulthood also constitutes a limitation. Longitudinal studies considering different age groups and demographic homogeneity and studies to support the effect of dimensions are needed. It is also necessary to examine cross-cultural differences. The quantitative methodology used in this study is another limitation. Therefore, qualitative studies are recommended.

CONCLUSIONS

This study emphasizes the importance of a healthy and happy childhood in emerging adulthood with the finding that happiness and peace experienced during childhood have a direct and positive effect on the DT and emotional intelligence dimensions, which play an active role in psychological well-being and the ability to cope with problems. This study corroborates research that detected the negative effects of childhood traumatic experiences and/or child maltreatment, which are widely addressed in the literature. In this respect, this study offers a different perspective on the development of preventive and interventional programmes regarding parent education in the future. Another contribution of the study is that it clarifies the emotional intelligence dimensions that have a direct mediating effect on the relationship between memories of childhood peace and DT. These findings will serve as a valuable resource for future research and aid counsellors and psychotherapists in developing preventive and interventional programmes. The study focused on the period of emerging adulthood, during which individuals commonly encounter difficulties and obstacles in achieving their future goals. Future research should utilize a longitudinal design that includes various age groups, including childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, to clarify and acquire further information on this subject.