BACKGROUND

A STUDY OF EVIL – THE DARK TRIAD AND INCLINATIONS TO MALEVOLENT BEHAVIOURS

The Dark Triad (DT) traits have become the most popular model of socially malevolent personality traits, comprising traits of subclinical narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Whereas all traits share the similarities of callousness, duplicity, and self-aggrandizement (Moshagen et al., 2018), each trait contains some unique characteristics. Narcissism describes a heightened sense of self-importance and grandiosity (Raskin & Hall, 1979); Machiavellianism describes a tendency to achieve long-lasting goals through strategic manipulation (Christie & Geis, 1970); and psychopathy describes impulsive and thrill-seeking behaviours (Hare, 1985).

Whereas there were attempts to reduce these traits to a common denominator, evidence from behavioural and experimental studies oppose these claims. For instance, Machiavellianism is a stronger predictor of soft and hard manipulation tactics in the workplace, while psychopathy is a stronger predictor of using punishment threats to achieve goals (Jonason et al., 2012). Furthermore, while psychopathy is linked to the neglect of potential costs, which decreases performance in strategic games involving resource control, Machiavellianism is connected to higher performance in resource control tasks because of greater strategic decision-making (Curtis et al., 2021). Thus, the debate regarding the redundancy of the DT is far from settled, raising the need for more nuanced research.

UNPACKING THE DARK TRIAD: A SIGNIFICANT PREDICTOR OF DARK TRAITS

The meaning of the common core of the DT and, thus, a hypothetical redundancy of the traits within DT, have recently been a debated topic. Such notions became a part of the discussion regarding the redundancy of the Dark Triad itself, especially considering similarities between the DT and other personality traits.

Previous suggestions included low agreeableness (Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006), low honesty-humility (HH; Lee & Ashton, 2005), or callousness and interpersonal manipulation (i.e., factor 1 psychopathy; Jones & Figueredo, 2013). In Paulhus and Williams’s (2002) DT paper, they identified low agreeableness as the only shared Big Five correlate among DT traits. Also, research found that all the DT traits load positively onto one factor, characterized by low agreeableness (Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006). It supports low agreeableness as a candidate for the common core of DT traits (Stead & Fekken, 2014). In the same vein, Vize et al. (2021) found that the latent correlation between the dark core and agreeableness was almost perfect (–.90). However, this general dark core served as an explanation not only for DT traits but also those understood as dark by many researchers on the topic (e.g. incivility, immorality, or domineering), providing rather indirect evidence towards agreeableness as the common core of the DT.

Lee and Ashton (2005), on the other hand, discovered that the shared variance of the DT is well-approximated by low HH, i.e., all DT traits were more strongly negatively correlated with HH than any of the Big Five traits, and correlations amongst the DT traits were better explained by the facets of HH than by the Big Five. Lee et al. (2013) corroborated this conclusion as they found that the common variance of the DT was highly saturated with HH and that both the DT and HH predicted relevant criterion variables that were not well predicted by the Big Five. Book et al. (2015) provided evidence suggesting that while both agreeableness and HH explain variance in the DT core, HH better captures the construct. Also, Hodson et al. (2018) found that the latent correlation between the DT core and HH was nearly perfect (r = –.95), with Aluja et al. (2022) documenting similar patterns of associations in cross-cultural studies.

Despite the strong evidence for the overlap between HH and the latent DT, some research has shown that this is not the full picture. For example, Moshagen et al. (2018) extracted a more general dark factor from a variety of socially aversive personality traits (including the DT) and found that it incrementally predicted relevant criteria over the effect of HH, indicating that even though HH offers substantial coverage of a more general dark core, it is not comprehensive. Also, McLarnon and Tarraf (2021), by studying DT traits, found that the relationship between HH and the DT core was weaker than or equal to the relationship between HH and the specific Machiavellianism factor, providing evidence against the notion that the DT core represents the inverse of HH. Moreover, Hilbig et al. (2020) found that the general dark factor showed differential and much stronger coverage of socially aversive psychopathologies than HH (or agreeableness), indicating that HH may not be equivalent to a general dark core. Research by Horsten et al. (2021) implied that the dark factor of personality (D) and low HH overlap strongly, but the dark core and low HH appear to be functionally and nomologically distinct. The core outperformed HH in predicting aversive traits, low HH better explained variance in pretentiousness, and the dark personality factor explained incremental variance over low HH in distrust-related beliefs and empathy. Hilbig et al. (2022) suggested that one trait may not be enough to statistically explain any dark core. It is broader than any one particular dimension within models of basic personality structure, because it includes a wider range of behaviours than any one basic personality trait. Dian et al. (2023) found that negative campaigning in elections is predicted more strongly by agreeableness and dark traits. When estimating a model including basic and dark traits, the effect of HH disappears, while the influence of agreeableness and DT traits remains significant. This suggests that the ability to predict dark personality traits is highly context-dependent for HH, DT, and other traits, supporting the idea that simplifying any dark core to one trait is impossible.

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated the possibility that the core of the DT does overlap with HH or agreeableness but is not equivalent to them (Schreiber & Marcus, 2020). In line with that, Scholtz et al. (2022) provided evidence that, although agreeableness, HH, and DT are strongly related to antagonistic traits, the DT is the most stable representation of antagonism. Hence, personality traits, such as HH, agreeableness, and DT, may encompass different features of antagonism (affective, behavioural, and cognitive, respectively), but only the DT contains most of them. When interpreting the relationship between HH and DT, one also needs to acknowledge that the HH and DT constructs stem from different traditions; while HH was derived to be a construct that is relatively orthogonal from other basic traits, DT may reflect various aspects of the HEXACO model.

Overall, there is little agreement in the literature regarding what the DT core represents. For the time being, the strongest candidate appears to be HH. However, this verdict needs further investigation.

VENGEFUL INCLINATIONS AND THE DARK TRIAD TRAITS

As the DT traits are described as socially aversive (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), they also share vengeful inclinations (Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2020). Revenge is a destructive behaviour attempting to restore one’s threatened self-image through getting payback for a perceived transgression to restore moral balance (McCullough et al., 2001). Accompanied by benevolence (i.e., kind-heartedness and forgiveness) and avoidance (i.e., building distance between victim and transgressor), it constitutes the three common post-transgression responses used to negotiate and/or re-establish a relationship after interpersonal disagreement (McCullough & Hoyt, 2002).

A recent study emphasized the role of DT in predicting revengefulness (Rebrov et al., 2022), with Machiavellianism and psychopathy being weakly to moderately but consistently associated with vengeance (Giammarco & Vernon, 2014). The role of narcissism is less straightforward, with weak and positive (Brown, 2004) or non-significant correlations (Giammarco & Vernon, 2014). It may be explained by the fact that grandiose narcissism comprises agentic (i.e., assertive self-enhancement through self-promotion) and antagonistic facets (i.e., entitled self-defence, exploitation, and arrogance). Whereas the former is typically studied in the context of the DT, it is the latter that is more strongly connected to Machiavellianism and psychopathy (Trahair et al., 2020). Studies emphasize that only the antagonistic facet predicts vengeance (Fatfouta et al., 2015, 2017). Thus, although the relationship between narcissism and vengeance is not obvious, it seems that all of the DT traits are connected to vengeance, suggesting that vengeance may be important in understanding dark personality traits in general.

Yet, we may also assume that HH is associated with revengefulness. Several studies showed that a higher level of HH correlated with lower preferences for vengeance (Lee & Ashton, 2012), which is understandable given that HH is conceptualized as governing one’s reluctance to exploit others (Ashton & Lee, 2007). Also, research found a consistent, positive link between HH and prosocial behaviours (Zhao & Smillie, 2015), e.g., altruism (Thielmann & Hilbig, 2014). At the same time, HH is more reflective of active cooperation (i.e., an inclination for fairness vs. exploitation), while agreeableness is more reflective of reactive cooperation (i.e., forgiveness, vs. revengefulness; e.g., Hilbig et al., 2016). Hence revengefulness may be a promising construct in potentially disassociating HH from the DT core, as this trait is conceptually more closely related to competing candidate constructs for defining the DT core.

CURRENT STUDY

Our study aimed to assess the overlap and distinctiveness of the latent DT from HH. Previous research has been sceptical regarding the DT’s incremental value as it is seen as redundant and adds little to traditional personality models (Muris et al., 2017). Hodson et al. (2018) supported this claim, demonstrating that the latent correlation between the DT and HH is nearly perfect. However, conclusions derived from that research seem to be premature.

First, Hodson et al. (2018) employed only one method of DT assessment, i.e., the Short Dark Triad (Jones & Paulhus, 2014). While practically useful, this measure might be less appropriate than standalone measures because it insufficiently addresses the multidimensionality of the DT traits (Back et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2009). The second limitation concerns the lack of construct validity evidence. Undoubtedly, a near-perfect correlation is evidence of constructs’ overlap. However, claims about the constructs’ redundancy should be supported by disproving sameness through testing of conceptual differences, such as the strength of their relations to other constructs, which allows one to analyse a deeper level of construct validity and more nuanced understanding of the investigated constructs.

Thus, in our study, we aim to overcome both limitations. We employ multidimensional measures of narcissism and psychopathy and a standalone measure of Machiavellianism. Furthermore, we assess the relations between the DT, HH, and revengefulness. We expect to find a significant and strong negative correlation between the DT and HH composite scores and a stronger relationship between DT and HH latent scores. Thus, we expect that the link between the DT and HH will emerge regardless of the method used (H1). Still, given the differences between these constructs, we expect to find divergence in how they relate to revengefulness. As there is a substantial overlap between DT and revengefulness, we expect that DT will be more strongly related to revengefulness than HH (H2).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The sample consisted of 677 participants aged 18 to 55 years old: 551 women (Mage = 22.57, SDage = 4.31), 111 men (Mage = 23.66, SDage = 5.32), and 15 non-binary people (Mage = 24.67, SDage = 3.42). Participants were anonymous Polish residents recruited using snowball sampling via social media. The present study was part of a larger data collection and was not pre-registered.

MEASURES

Revengefulness. Revengefulness was measured as a strategy for coping with interpersonal transgressors using the Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Inventory (TRIM; McCullough et al., 2006).

Narcissistic admiration and rivalry. Narcissism was assessed using the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ; Back et al., 2013).

Machiavellianism. To assess Machiavellianism, we used the MACH-IV (Christie & Geis, 1970).

Psychopathy. Psychopathy was measured with the shortened Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TRIPM-41; Patrick, 2010).

Honesty-humility. The HH dimension of the HEXACO was measured with the HH subscale of Polish Personality Lexicon (Szarota et al., 2007).

Further information about all measures, data, and statistical codes are provided on the OSF page: https://osf.io/v2rmz/?view_only=6307c63ddf4e48179fd0efb3f096b86c

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

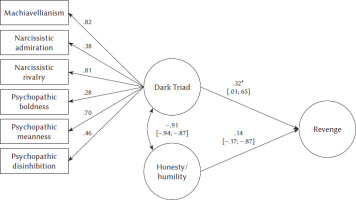

We computed a composite score of the DT as a mean of the six scales described above and a composite score of the HH. To test the hypotheses, we used structural equation modelling. The model included confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models for each scale (including DT, HH, and Vengefulness). Also, we modelled second-order DT latent variables out of the scales estimated from the CFA. Finally, we regressed vengefulness on DT and HH.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are presented in Table 1. The correlation between the DT and HH composite score equalled r = –.71 [–.75; –.67], p < .001; and thus was within the expected range, supporting H1. The tested SEM model was well fitted according to RMSEA (.050 [.049; .051]), but poorly according to χ2(6545) (17540.53, p < .001) and CFI (.655). The correlation between latent variables was considerably higher and approached unity (ρ = –.91, p < .001).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and zero-order relations between study variables

As shown in Figure 1, which presents the structural part of the model, despite the extremely high correlation between the latent DT and HH, only DT was uniquely related to revengefulness after accounting for its shared variance with HH, thus supporting H2.

DISCUSSION

In the study, we examined the link between the DT and HH, demonstrating that these dimensions are highly correlated and replicating the results of Hodson et al. (2018) using a broader array of measures. Our results support a strict conceptual overlap between both dimensions (e.g., Muris et al., 2017), proving that the shared variance between these traits is more considerable when analysed as latent factors. This finding supports the idea that the dark traits exemplify a more general behavioural inclination to maximize one’s gains regardless of the costs, accompanied by the belief that they are truly justified (Moshagen et al., 2018). As such, the dark factor (Hilbig et al., 2020) shapes malevolent traits of normal personality (e.g., low HH) and those associated with psychopathology.

However, although the dark core represents some commonalities of the aversive aspects of human nature, it is impossible to simplify it into an essential personality dimension. Our study provides evidence for this notion by presenting significant divergence in the relations between DT, HH, and revengefulness. That is, the higher level of DT traits favours a higher revengefulness, and HH predicted only a lower proneness to exact revenge. Hence, despite the strong relationship between DT and HH, both traits seem to behave differently when other psychological dimensions are considered.

Indeed, the DT predicts revengefulness in aspects of daily life, e.g., romantic revenge for infidelity (Brewer et al., 2015) or vengeful road behaviours (Wiesenthal et al., 2000). Although HH was shown to predict vengeful behaviour (Lee & Ashton, 2012), our results suggest that the DT might play a greater role in explaining them.

Our results raise some questions regarding the nature of the dark core of the DT traits. Consistent with Hilbig et al. (2020), the dark core of personality seems to be somehow distinct from HH, accounting for variance in antagonistic or exploitive traits beyond this basic personality trait. Therefore, contrary to the interpretation by Hodson et al. (2018), despite great overlaps between the DT and HH, the DT cannot be reduced to the low pole of HH. In line with Horsten et al. (2021), we claim that latent DT and HH overlap yet function differently and remain nomologically distinct. While the HH dimension was derived inductively from lexical studies and tended to reflect (theoretically) orthogonal dimensions of basic personality structure, the DT is composed of several aspects of the HEXACO. As such, it is associated with its personality dimensions (Schreiber & Marcus, 2020). Thus, although HH and DT share some features, they do not represent the same construct and play different roles in determining aversive traits. Most importantly, the two traits do not share the exact extent of disutility infliction towards others and justification of malicious behaviours, which are evident for a higher pole of DT and may not necessarily be present in the case of low HH. The present study has both strengths and limitations. The main strength is that it overcomes the weaknesses related to the previous research by Hodson et al. (2018), i.e., the employment of the singular method of assessment of the DT and the lack of evidence of construct validity. Also, our study replicates the important findings on overlap between DT and HH in a large, non-WEIRD (white, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) sample (Henrich et al., 20101).

Yet, the sample itself may also present some limitations. First, the sample comprised Polish residents, with a very high over-representation of women and relatively young participants, which may impair the generalizability of the results. Thus, we recommend caution while formulating conclusions about other populations, suggesting further replication of our findings.

The second limitation is the use of snowball sampling. While it is a widely used and both cost- and time-effective sampling method (Leighton et al., 2021), its drawback lies in the limited scope of social networks accessible through such techniques, i.e., only members who share networks can participate. Thus, its final composition may demographically diverge considerably from the population of interest (Kendall et al., 2008). Also, as we used social media channels (e.g., Facebook) for recruitment, the sample composition may share the disadvantages of all online-recruited samples, i.e., respondents’ younger age, prosperousness, with predominantly female participants and lack of minorities (Moseson et al., 2022). In the case of our sample, the limited representativeness is mirrored in the presence of young participants. Yet, the possible discrepancies might be more far-reaching, demanding more research to corroborate the results obtained in our study.

Third, all measures were self-report measures. Hence, we recommend investigating the structure of the DT using other methods, such as a multi-method approach.

Regarding statistical analyses, it must be noted that the fit indices of the tested model were mixed, i.e., suggesting both good (i.e., RMSEA) and poor model fit (i.e., CFI), with several possible reasons for such results. First, we did not introduce any post-hoc modifications into the model (i.e., correlated residuals). Second, some of the used measures (e.g., MACH-IV) are well known for their unstable factorial structure, which may impact the overall fit to the model. Finally, in a model with a large number of variables, the CFI tends to be artificially low (Kenny & McCoach, 2003). Thus, considering all these limitations together, the fit indices should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, there are some limitations regarding measures. Using the lexical dimension extracted from the Polish language is meritorious, adding a novel aspect to the debate regarding conceptual overlap between certain personality traits. Regardless, Szarota et al. (2007) clearly suggested that the “Polish” HH dimension is not identical to the English version (although their correlation was substantial), as not all original words had “perfect” translations into Polish, being similar than rather identical to the original personality descriptors. It may cause problems with the comparison of the results acquired in other research.

The present study demonstrated that the DT (composite and latent) and HH (composite and latent) are almost perfectly correlated. Despite these high correlations, the DT and HH differ considerably in predicting revengefulness. Therefore, our findings indicate that even though the overlap between these dimensions is exceptionally high, suggestions that they are equivalent are premature.

ENDNOTE

1 We assumed that a WEIRD country is characterized by five features: (1) affiliation to Western culture; (2) higher quality of education; (3) higher industrialization; (4) higher economic development; and (5) democratic government. Thus, despite Poland being predominantly well educated, with an ever-growing industrial and economic development, it is part of an Eastern or Middle-Eastern (not Western) cultural background. Also, even though, for now, Poland remains democratic, the struggles within its political system are significant (in terms of democracy and the rule of law erosions; e.g., Drinóczi & Bień-Kacała, 2021).

Supplementary materials are available on the journal’s website.