BACKGROUND

Insomnia is a widespread and serious disorder that interferes with the normal functioning of a significant portion of society. Bhaskar et al. (2016) reported that the prevalence of insomnia in the general population may be between 10% and 30%, perhaps even as high as between 50% and 60%. Cunnington et al. (2013) drew attention to the consequences of insomnia, such as fatigue, cognitive functions disorders, mood changes, weakening of motivation, work absenteeism and increased risk of road accidents due to falling asleep behind the wheel. Additionally, insomnia can contribute to social withdrawal and loneliness (Ben Simon & Walker, 2018), social stress and problems in close relationships (Gordon et al., 2017), as well as depression and anxiety (Taylor et al., 2005).

According to Pavot and Diener (1993), satisfaction with life (SWL) derives from the degree to which a person’s perception of their life aligns with their expectations. Degree of SWL, therefore, is based on a self-assessment of one’s own life, with higher levels indicating greater compatibility between subjective assessment and the ideal. Insomnia was associated with changes in SWL scores in a number of clinical group studies. For example, some studies demonstrated that insomnia was associated with lower levels of SWL after mild traumatic brain injury (Agtarap et al., 2021); in people living with HIV/AIDS (Rogers et al., 2020); and, to a greater extent, in people suffering from psychological problems (e.g., depression, insomnia, stress/anxiety) compared to people suffering from somatic diseases (e.g., cancer, migraine) (Vázquez et al., 2015). The relationship between insomnia and SWL has also been demonstrated in studies of nonclinical groups, namely Hong Kong high school students (Chan et al., 2018) and American adults (Karlson et al., 2013).

Numerous researchers have pointed out that insomnia is comorbid with somatic and mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder (Hertenstein et al., 2019; Sivertsen et al., 2021). Both Lombardo et al. (2018) and Rissanen et al. (2013) emphasized that people who assessed their mental health as poor also had low levels of SWL, irrespective of income differences, general health and gender. Furthermore, the relationship between mental health indicators and SWL appears to be bidirectional. Fergusson et al. (2015) demonstrated that SWL affects mental health, and, conversely, mental health affects SWL levels. According to Guney et al. (2010), SWL levels should be taken into account as a moderating factor in mental health research.

As mentioned earlier, both insomnia and SWL levels may be associated with mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. Such an association may also suggest a relationship between the affective temperaments described by Akiskal and Akiskal (2005) that are responsible for mood disorders – that is, depressive, cyclothymic, hyperthymic, irritable and anxious – and insomnia and SWL. While the relationship between affective temperament and insomnia has been shown in several previous studies (Deguchi et al., 2017; Oniszczenko et al., 2019; Toyoshima et al., 2021), the association between affective temperament and SWL remains unclear.

Affective temperaments are biologically determined, and stable personality traits determine a person’s mood and the predisposition to develop affective disorders (Rovai et al., 2013). A depressive temperament is associated with low energy and motivation levels and aversion to engaging in activities related to arousal. People with a cyclothymic temperament are predisposed to develop bipolar disorder and possess fluctuating energy levels, self-esteem and social relationships while at the same time being highly creative. An irritable temperament is associated with over-reacting to stimuli, becoming easily angry and resorting to violence. A hyperthymic temperament manifests as a primarily optimistic attitude toward life, sensation seeking, and high activity in everyday life (Kwapil et al., 2013). People with an anxious temperament tend toward constant mental and physical tension and rumination (Vazquez & Gonda, 2013).

In a previous study, we found that certain affective temperaments (cyclothymic, anxiety and hyperthymic) were directly and indirectly related to the symptoms of insomnia and that level of energy as a component of mood mediated this relationship (Oniszczenko et al., 2019). In the current study, we aimed to reaffirm the relationship between affective temperaments and insomnia and to determine whether affective temperaments are associated with SWL and whether SWL can mediate the relationship between affective temperaments and insomnia. We hypothesized that (1) affective temperaments were associated with SWL, and (2) SWL, due to its relative stability compared to mood, may mediate the relationship of affective temperaments and insomnia and that a high level of SWL may reduce the risk of insomnia.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study involved 497 participants aged 18 to 67 years (M = 29.19 years, SD = 9.47 years), including 435 women and 62 men. The minimum sample size sufficient for the study aims was 385 (α = .05, power = 0.95). Table 1 presents sociodemographic details of the study participants.

Table 1

Sociodemographic variables in the studied sample (N = 49/)

PROCEDURE

All participants were recruited from the general population via an online recruitment platform. The sole inclusion criterion was that participants be at least 18 years old. Prior to beginning, all participants were informed through an online message that the study was anonymous, voluntary and they could withdraw from it at any time without giving a reason and that commencing the study served as providing informed consent. This research procedure was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Warsaw, Faculty of Psychology (ref: 1-11-2021).

MEASURES

The Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego Autoquestionnaire. The Polish version of the Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego Autoquestionnaire (TEMPS-A; Akiskal et al., 2005; Borkowska et al., 2010) was used to diagnose affective temperaments. This self-reporting questionnaire contains 110 items (109 for men) and a yes/no response format scored on a scale of 1 to 10. Cronbach’s α coefficients for individual scales in the study sample were as follows: depressive α = .77, cyclothymic α = .84, hyperthymic α = .82, irritable α = .80 and anxious α = .88.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale. The SWL level was assessed by the Polish version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985; Jankowski, 2015). The SWLS comprises 5 items with a 7-point scale, ranging from 7 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in the studied sample was .89.

The Athens Insomnia Scale. The Polish version of the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS; Soldatos et al., 2000; Fornal-Pawłowska et al., 2011) was used to assess the level of insomnia symptoms in the studied sample. The AIS contains 8 items scored from 0 to 3. Higher values indicated a higher level of insomnia symptoms. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale in the studied sample was .85.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM’s SPSS 27 Statistics software. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to estimate the effect of affective temperaments and SWL as predictors of insomnia symptoms. The PROCESS macro for SPSS version 3.5 was applied for the mediation analysis (Model 4) (Hayes, 2018). Additionally, the bootstrapping procedure (5,000 sample draws, 95% confidence intervals) was used to estimate the direct and indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between variables. SWL correlated negatively with insomnia symptoms. Depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments correlated positively, but hyperthymic temperament correlated negatively with insomnia symptoms. Hyperthymic temperament correlated positively with SWL, but depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments correlated negatively with SWL.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and Pearson r correlations for the study variables (N = 49/)

Table 3 provides the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. Different levels of SWL caused most of the variance in insomnia symptoms (17%), and the presence of cyclothymic and anxious temperaments increased the variance by 13%. Together, SWL and cyclothymic and anxious temperaments cause 30% of the variability in insomnia symptoms (with an effect size of f2 = 0.43).

Table 3

Hierarchical regression analysis of the satisfaction with life and affective temperaments as predictors of insomnia in the whole sample (N = 49/) with variance inflation factor (VIF)

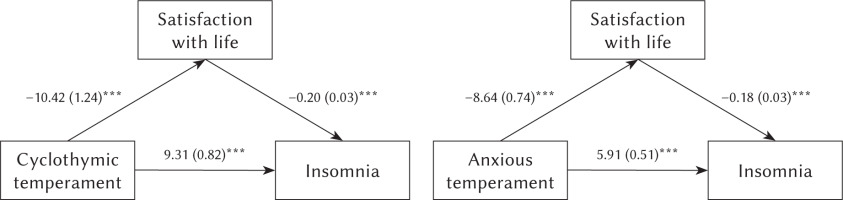

Two independent analyses of mediation with a bootstrapping procedure were performed using SWL as a mediator first between cyclothymic temperament and insomnia, and then between anxious temperament and insomnia. The first analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of cyclothymic temperament on insomnia in relation to SWL (effect = 2.11, SE = 0.41, 95% CI [1.36, 2.99]). The second analysis showed a significant indirect effect of anxious temperament on insomnia through SWL (effect = 1.55, SE = 0.30, 95% CI [0.99, 2.18]). Figure 1 shows individual pathways in the mediation analyses.

Figure 1

Relationship between cyclothymic and anxious temperaments and insomnia symptoms as mediated by satisfaction with life

Note. The mediating effect of satisfaction with life in the relationship between cyclothymic temperament and insomnia (left) and in the relationship between anxious temperament and insomnia (right). Unstandardized coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

The results of correlation analysis reaffirm the relationships between affective temperaments and insomnia as we have previously shown (Oniszczenko et al., 2019). In this study, two correlation coefficients between cyclothymic and anxious temperaments and symptoms of insomnia stand out from other correlation coefficients between affective temperaments and insomnia (see Table 2). These results are in line with the general characteristics of affective temperaments. As Vázquez and Gonda (2013) have indicated, people with cyclothymic temperaments are characterized by considerable variability in terms of sleep: “alternating from reduced need for sleep to hypersomnia” (p. 22). Similarly, “people with a predominantly anxious temperament, typically characterized by constant tension, inability to relax, uncontrolled worry and irritability” (p. 69), may also be at risk of insomnia (Akiskal, 1998).

We also confirmed the association between affective temperaments and SWL. Depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments were negatively correlated with SWL (see Table 2). However, this result requires further explanation using a behavioural-genetic hypothesis.

Pavot and Diener (2008) showed that SWL level is associated with depression as well as neuroticism, a risk factor in common mental disorders, including anxiety and depression (Jeronimus et al., 2016). Guney et al. (2010) also confirmed the association of SWL with anxiety. Moreover, as this study has shown, the association of SWL levels with depression and anxiety also suggests an association between SWL levels and affective temperaments.

Another underlying cause of the association between affective temperament and SWL may be the strong positive correlation between the four affective temperaments and neuroticism, as demonstrated in two previous studies (Blöink et al., 2005; Oniszczenko et al., 2019). We hypothesise that affective temperament and neuroticism play similar roles in regulating an individual’s mental health. Significantly, neuroticism and SWL may share genetic and environmental bases. As demonstrated by Sadiković et al. (2019), common genetic and environmental factors explained the phenotypic correlation between neuroticism and SWL. Similar results were obtained by Røysamb et al. (2018), who demonstrated a genetic correlation between anxiety and depression as components of neuroticism and SWL as well as between activity and positive emotions as components of extraversion and SWL. Likewise, Nes et al. (2013) detected both genetic and environmental correlations between major depression and SWL.

In addition, our results showed a negative correlation between SWL and insomnia symptoms (see Table 2). This result confirmed our hypothesis and suggests that a high SWL level may help to reduce the symptoms of insomnia. Furthermore, this result corroborated previous findings on the relationship between sleep and SWL. For example, Ness and Saksvik-Lehouillier (2018) established that sleep quality and variability of sleep (i.e., unstable bedtime and waking up time) were associated with SWL among university students. Shin and Kim (2018) confirmed that sleep quality is a good predictor of SWL among undergraduate students. Nauman et al. (2019) found that anxiety and insomnia as mediators of work stress and SWL may decrease levels of SWL. Paunio et al. (2009) observed that both poor sleep quality and sleep length diminished SWL levels. Finally, Kim et al. (2021) reported that elderly people with a high level of SWL also exhibited fewer sleep problems.

It is worth noting that some molecular genetics research data suggest that affective temperament, SWL, and insomnia share a genetic basis, thus explaining their phenotypic correlations observed in our study. For example, according to Rihmer et al. (2010), depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious temperaments are strongly associated with the serotonergic system, while hyperthymic temperament is strongly associated with the dopaminergic system. Similarly, Lachmann et al. (2021) confirmed the association of polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR with satisfaction, but only with respect to housing, leisure and family life, not as an indicator of overall SWL. The relationship between 5-HTTLPR and SWL was previously confirmed by De Neve (2011). Furthermore, Deuschle et al. (2010), Huang et al. (2014) and Lind and Gehrman (2016) confirmed the relationship between 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and insomnia. In one study, Kovacic-Petrovic et al. (2019) revealed the association of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and insomnia in a group of non-depressive veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Associations between 5-HTTLPR and all our study variables suggest a common genetic background.

Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that SWL and two affective temperaments – cyclothymic and anxious – were good predictors of insomnia. Mediation analysis showed that affective temperament may both directly and indirectly influence symptoms of insomnia. SWL is an important mediator between affective temperament and insomnia, confirming our hypothesis. According to Diener et al. (2012), positive feelings and absence of negative feelings contribute to an increase in SWL. Meyer et al. (2004) confirmed the relationship between major depression and anxiety disorders and SWL levels in the German adult population. Comorbidity was correlated with low level of SWL in the study sample. It can therefore be assumed that the low intensity of affective temperaments related to mental disorder will foster a reduction of negative feelings and an increase in positive feelings, thereby promoting higher SWL levels and contributing to better mental health, including the reduction of insomnia symptoms.

Finally, we would like to mention the limitations of our study. Although relatively large, the majority of our sample were women and participants with higher education, which makes generalizing the results problematic. We did not control for factors relevant to the diagnosis of the variables under study, such as existing mental disorders or diseases, or history of medical procedures related to mood. In addition, the cross-sectional design of our study significantly limits the possibility of assessing the causal relationships between study variables.

CONCLUSIONS

Regardless of these limitations, our study reaffirmed associations between affective temperaments and insomnia and showed that affective temperaments are also associated with SWL. Cyclothymic and anxious temperaments can influence the symptoms of insomnia directly and indirectly as mediated by SWL.