BACKGROUND

When we speak about personality, we put into words the way we function interpersonally and our individual differences, understood as our collection of thoughts, behaviours, and emotional patterns (Allport, 1961). Since this definition, several models of personality have been developed to cover and explain these patterns of behaviour.

On the one hand, there is a theory whose main objective is to explain and describe the “dark” personality, that is, the malevolent personality. This construct of aversive personality is called the Dark Triad and is composed of a set of three traits that Paulhus and Williams (2002) described to form it: Machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism. Although each of the traits describes individual antisocial characteristics that lead to different negative outcomes, the three of them have some similarities, building this model of aversive personality (Muris et al., 2017). More specifically, Machiavellianism can be defined as a cunning and deceitful way of behaving in which such individuals pursue only their own goals without thinking about the means used to achieve them, mainly manipulating others by exploiting them as mere resources (Fehr et al., 1992). Those with high scores in narcissism are self-centred people with grandiose feelings of superiority to others, a high sense of entitlement and often attention seeking (Raskin & Hall, 1981). The last trait is psychopathy, which differs from the clinical idea of psychopathy, is characterized by callous personalities with low morality and almost no empathy, who look for activating activities even if this implies antisocial behaviours (Hare, 1999).

On the other hand, Eysenck and Eysenck (1975) developed the PEN model to describe the spectrum of common patterns of thinking and behaving. This model – “the Big Three” – is also composed of three traits of personality: neuroticism, extraversion, and psychoticism. Neuroticism, as opposed to emotional stability, describes a pattern of high affectivity, trait anxiety, and mood instability, which is related to impulsivity and risk-taking (Peters et al., 2020). Extraversion, as opposed to introversion, describes a person with a tendency to interact with the environment while relating to other people and externalizing their emotions and feelings. And finally, psychoticism, the opposite of warm-heartedness, is the most antisocial trait as described by Eysenck. It is characterized by a lack of empathy, aggressiveness, and hostility to others, implying risky behaviours in the pursuit of arousing sensations. Following these descriptions, it can be inferred that the construct of psychoticism is the most closely related to the Dark Triad personality (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Some authors even consider psychoticism to be the same construct as psychopathy (e.g., Kajonius et al., 2016).

After Eysenck developed his model of personality, other authors attempted to cover and explain all the possibilities of personality. These are mainly the Five-Factor (FFM; Goldberg, 1993) and the HEXACO (Ashton & Lee, 2001) models of personality. Although these new models of personality conceptualize personality in a more complex way, the PEN model is still used due to its simplicity and the fast application of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised-Abbreviated (EPQR-A; Francis et al., 1992; Pineda et al., in press). Additionally, the EPQR-A presents a “lie” or a sincerity scale, that measures the bias to “fake good” as a sincerity scale.

In this context, another question arises: are people with malevolent traits sincere? Based on the literature, it seems important to consider social desirability when examining undesirable behaviours and personality traits, such as drug use, unethical behaviour or malevolent personality traits, as it is more likely that people who score high on these behaviours or traits may manipulate their responses to present themselves as more socially desirable (Althubaiti, 2016; Andrews & Meyer, 2003; Echeburúa et al., 2011; Rogers et al., 2002; Spaans et al., 2017; Vigil-Colet et al., 2012). Therefore, it seems relevant to ask whether people with Dark Triad traits are sincere or whether, given their deceptive and manipulative nature, these people would present themselves as more desirable when responding in a self-report (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). There is extensive research investigating the links between the Dark Triad and the other two models of personality (FFM and HEXACO; Kayiş & Akcaoğlu, 2021; Muris et al., 2017; O’Boyle et al., 2015). Moreover, some research has investigated the connections between the three-factor theory of personality and antisocial behaviours (e.g., Cale, 2006). But there is hardly any research linking the Dark Triad itself with this “Big Three”. Furthermore, the literature on this area reaches different conclusions (Mohammadzadeh & Ashouri, 2018; Pineda et al., 2020).

THE PRESENT STUDY

Therefore, with this investigation we aim to clarify the connections between these important models of personality, including the analysis of sincerity, and considering measurement error using structural equation modelling (SEM). According to the nature of the constructs of each personality trait from the models and previous studies, we expect that all the Dark Triad traits will present significant positive connections with psychoticism since this trait is described as the most antisocial one from the PEN model of personality, psychopathy being the most related to it because of their similarities (Mohammadzadeh & Ashouri, 2018). Taking into consideration that narcissism is a trait that presents multiple dimensions (i.e. vulnerable and grandiose narcissism), we consider that it will be related to neuroticism due to their similarities in high sensitivity, as well as to criticism from other people (Curtis & Jones, 2020). We do not have any predictions regarding Machiavellianism, besides the previous one linking it with psychoticism due to its antisocial nature (Mohammadzadeh & Ashouri, 2018).

Regarding the additional measure of the EPQR-A, the sincerity scale, we anticipate that people with high scores in the three Dark Triad traits will obtain higher scores on this scale. We expect this result as a consequence of their lack of concern about what other people think of them, only manipulating their image and thus the answers given in a questionnaire when there are specific objectives or purposes to be achieved (Carré et al., 2020; Fehr et al., 1992; Hare, 1999).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The participants for this study were recruited for three years, from 2017 to 2019. From a large sample of 4584, N = 2385 met the inclusion criteria (being older than 18 years old and having completed the study measures), 1727 were women (72.4%) and 658 men (27.6%), with an average age of 28.98 (SD = 10.39), most of them Spanish (85.45%) or South American (12.70%) and highly educated (without basic studies 0.15%, primary school 8.99%, high school or vocational training 28.64%, university studies 62.13%).

PROCEDURE

The recruitment was conducted using a convenience sampling method on the Internet, through social media such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and other similar sources. The database is submitted to a public repository. The study received ethical approval from the University Bioethics Committee (approval number DPS.JPR.04.16).

MEASURES

Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (DTDD). The DTDD (Jonason & Webster, 2010) is a questionnaire that measures narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy with four items per trait, twelve in total. Participants answer the items on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale applied was the Spanish translation of the Dirty Dozen (Pineda et al., 2020). For our sample, the internal consistency values were α = .82, ω = .83 for narcissism; α = .77, ω = .79 for Machiavellianism; and α = .64, ω = .60 for psychopathy.

Abbreviated form of the Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQR-A). The EPQR-A is a personality test developed by Francis et al. (1992) from the original EPQ (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975) and adapted to Spanish by Sandín et al. (2002). This questionnaire measures three personality traits (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, and psychoticism) and uses one validity scale (i.e., sincerity) divided into 24 items with dichotomic yes/no answers. The internal consistency values for our sample were α = .75, ω = .71 for neuroticism; α = .83, ω = .84; for extraversion; α = .46, ω = .50 for psychoticism; and α = .56, ω = .52 for sincerity.

DATA ANALYSES

Two programs were used to analyse the data: SPSS version 23 to obtain the descriptive statistics and the bi-variate correlations, and R for the structural equation modelling to obtain the confirmatory factor analysis, the path model and the ratio of variance accounted for in the Dark Triad scales by the EPQR-A. The structural equation modelling was performed with the Lavaan package. To estimate parameters, we used the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) procedure because it presents high accuracy and is specially developed for ordinal data, not starting with the assumption of normality in the distribution.

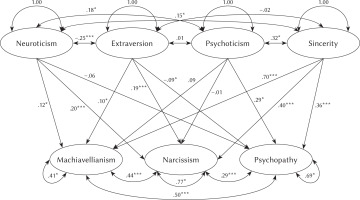

The path model (Figure 1) was developed including the two models of personality and paths from the Eysenck model to the Dark Triad. The fit indices that we used for fit interpretation were the comparative fit index (CFI), normed-fit index (NFI), goodness-of-fit statistic (GFI), the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The model fit would be considered good if SRMR was equal to or less than .05 (acceptable until .08), RMSEA equal to or less than .08, CFI greater than or equal to .95, GFI greater than or equal to .90, NFI greater than .90 and a non-significant χ2 due to the sample size.

Figure 1

Structural equation modelling of the EPQR-A predicting the Dark Triad

Note. EPQR-A – abbreviated form of the Revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Before carrying out the analyses mentioned here, a t-test was performed to analyse the possible differences between the means on the scales between participants of Spanish origin and participants of South American origin (country variable). As a result, only slight differences were obtained for the Machiavellianism and psychopathy subscales. For this reason, it was considered appropriate to consider it as a single sample and not to carry out the subsequent analyses separately. We believe that the lack of difference between means might be due to the difference in sample size and to the fact that the question on country referred to the country of origin and not to the country of current residence.

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available at https://osf.io/35kqb/ (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/35KQB).

RESULTS

Bivariate analyses were conducted to investigate the correlations between the Dark Triad traits, Eysenck’s major traits, and the scores of the sincerity scale of the EPQR-A instrument, as well as with sociodemographic variables (gender and age) (Table 1).

Table 1

Means (standard deviations) and correlations between the Dark Triad, the PEN model of personality, sincerity and sociodemographic variables

Regarding the connections between Eysenck’s three major traits and the Dark Triad, our predictions are supported by positive correlations between neuroticism and narcissism and, although not expected, Machiavellianism. Moreover, the correlational analysis shows connections between psychoticism and the three Dark Triad traits, psychopathy having the closer connection and narcissism the smaller one. Extraversion shows a significant negative connection – although very small – with psychopathy. In addition, and interestingly, the three Dark traits present strong and significant relationships with the sincerity scale of the EPQR-A.

After the correlational analyses, we conducted SEM to avoid, as stated before, measurement error and ensure that the connections between the measures taken were specifically as hypothesized and not due to other interactions. The SEM shown in Figure 1 presents quite a good fit (χ2 = 1102.74, DF = 573, RMSEA = .020, SRMR = .051, CFI = .979, GFI = .984, NFI = .958).

After adding the structural paths to the SEM, the sincerity scale from the EPQR-A turns into a predictor of the scores in the Dark Triad, β = .36 for psychopathy, β = .40 for narcissism, but being the highest for Machiavellianism with β = .70. Nevertheless, these are not the only noticeable connections of our path model; both narcissism and Machiavellianism are predicted by neuroticism and extraversion, with a β of .20 and .19 for narcissism and a β of .12 and .10 for Machiavellianism; psychopathy appears to be related to high scores on psychoticism (β = .29), as expected, but low on extraversion (β = -.09).

The ratios of variance accounted for in the Dark Triad scales by the EPQR-A were R2 = .58 for Machiavellianism, R2 = .23 for narcissism, and R2 = .28 for psychopathy (mean, R2 = .36).

DISCUSSION

Although the three-factor theory of personality (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975) remains one of the most important models of personality and it is still used thanks to its simplicity in the traits compared with the Big Five or the HEXACO, there is barely any investigation linking these three supertraits of personality (i.e. extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism) with the antisocial model of personality, the Dark Triad composed by Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Even though the PEN model does not capture the whole variance of the Dark Triad, it has shown the following connections between their assessed traits. Machiavellianism presents its main connection with neuroticism, similarly to the results of Mohammadzadeh and Ashouri (2018), which may be explained by the anhedonic and alexithymic moods, and characteristics of those people with high scores on Machiavellianism and neuroticism (Cale, 2006; Fehr et al., 1992). Also, as expected (Pineda et al., 2020), people with high scores in narcissism display a neurotic personality, probably because of some similar personality tendencies (i.e., high sensitivity to criticism or low tolerance to frustration); moreover, in accordance with Mohammadzadeh and Ashouri (2018), extraversion is also related to narcissism, presumably because of the tendency of those people with high scores in narcissism to show their greatness as well as their necessity to be accepted, going so far as to perform good deeds for others (Cale, 2006; Raskin & Hall, 1981; Trahair et al., 2022). As anticipated, psychopathy was predicted by high scores in psychoticism, which is a normal result due to the similarity of these two constructs (Mohammadzadeh & Ashouri, 2018; Pineda et al., 2020). However, this does not imply a perfect correlation, fuelling the discussion about whether they are or are not the same construct (Kajonius et al., 2016). Also, even if the relationships are weak or non-significant, the slight tendency in people with higher scores in psychopathy to be introverted and emotionally stable could be explained by their difficulties to socialize mediated by their lack of interest and ability to understand and share others’ feelings, in combination with their usually low anxiety levels (Hare, 1999).

An additional finding of this investigation is the tendency of the Dark Triad personalities to be sincere in their answers or, in other words, to exhibit low social desirability. Partially in line with Kowalski et al. (2018), the results we obtained show that those people with high scores in the Dark Triad traits do not place special importance on the image they project, accepting behaving in ways sometimes considered as socially undesirable. Our findings differ from the results obtained by Kowalski et al. (2018) for the narcissism trait; while they found a positive association between this trait and the social desirability variable, our results suggest the opposite. This difference as well as the direct association between the other two Dark Triad traits and the sincerity scale might be explained by the nature of the items of the sincerity scale that has been used. Some examples of these items are: “Have you ever taken advantage of another person?” and “Have you ever wanted to help yourself more than to share with others?”. These items were developed to assess the acceptance of some antisocial tendency that is believed to be present in almost everybody, thus presenting some similarities with the items of the Dark Triad.

These results do not run counter to the deceptive nature of the Dark Triad (Baughman et al., 2014). This might be explained by the fact that in this situation, respondents do not obtain any benefit from modifying the image given, which in another situation with such benefits would also imply a distortion in the Dark Triad questionnaire answers. Interestingly, the trait most related to the sincerity scale is Machiavellianism, which is characterized by being associated with the use of manipulative strategies, for example, modifying the answers given in a questionnaire depending on the context (Fehr et al., 1992). Perhaps, in a forensic assessment context, people with high scores on these traits are more likely to be biased in their assessment and appear more socially desirable (Echeburúa et al., 2011; Spaans et al., 2017).

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

One of the limitations of our study concerns the instruments used. First, the Dark Triad, although it presents good reliability coefficients, can be considered as an exploratory or screening measure due to its simplicity. It has also been attacked due to some mismeasurements at the core of the Dark Triad (Kajonius et al., 2016). Hence, the use of other more specific measures for each Dark Triad trait would be ideal.

On the other hand, the sincerity scale of the EPQR-A might not be optimal for this measurement since it was developed as a validity scale with a significant antisocial burden. Moreover, the reliability values of this scale are low, which is another limitation of this study. Therefore, it would be interesting to further investigate the sincerity shown in these personalities with different instruments and, furthermore, to include sincerity items to generate more objective measures for assessing these traits. Finally, the psychoticism scale also has low internal consistency values, which may also explain why it did not correlate more strongly with Dark Triad psychopathy.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, even though there is extensive research linking the Dark Triad with other models of personality such as the Big Five or the HEXACO (Muris et al., 2017; O’Boyle et al., 2015), the relationship between another well-established model of general personality, the PEN model, was not specifically covered. Hence it is relevant to map the links between Eysenck’s model and the Dark Triad, because of the importance of this latest model for predicting antisocial or conflictive behaviours (Muris et al., 2017). And although the supertraits of the PEN model of personality cannot capture the whole variance of the Dark Triad traits, it shows relevant connections.

Finally, the sincere answers given by people with high scores in the Dark Triad traits might have some implications. Taking into consideration the deceptive and manipulative nature of the Dark Triad (Baughman et al., 2014), these results would imply that these traits could be mismeasured in some contexts. Additionally, given these results, the idea arises that, perhaps, high scores on dark traits lead to these people not giving as much importance to how others see them. It also raises the possible idea that we have only detected people with high scores on dark traits who, in turn, are more sincere. Perhaps people with such traits who are insincere were not detected in this study. Therefore, this suggests that further efforts should be considered to develop more objective measures to assess Dark personalities, such as implicit, indirect, task-based, or forced-choice personality assessments, as well as to include scales measuring social desirability in self-reported assessments (e.g., Fronczyk & Witkowska, 2020; Santacreu & Hernández, 2018).