BACKGROUND

In the twenty-first century, global societies face various demographic issues, one of which is the increasingly mobile population. The immigrant flows of the past four decades have created large immigrant communities in Europe and North America, and the trend continues. This change at the global level is reflected in community and neighborhood changes (Abubakar et al., 2018; Clark, 2006). A majority and growing proportion of the world’s population lives in urban areas. The share of the world’s population living in urban areas is expected to increase from 55% in 2018 to 60% in 2030 (United Nations, 2018), making the creation of a healthy urban environment a policy priority.

Living in urban areas has been linked with a higher risk of mental disorders, and more than a century of research confirms higher risk of most mental disorders among persons living in urban versus rural areas (Faris & Dunham, 1939; Galea et al., 2005; Galea & Vlahov, 2005; Mair et al., 2008). Some theorize that for people, as for most animals, overpopulation and overcrowding are the main causes of violence (Biles, 1975), which can lead to heightened anxiety and a sense of uncertainty in the population. However, more research is needed to explain negative attitudes, aggression, and xenophobia among some residents of urban areas.

Anxiety and uncertainty can sharpen sensitivities in urbanites. One of these sensitivities is known as urban socio-spatial disorder sensitivity (UDS), which describes individuals with a higher sensitivity to the social aspects of living in the city, specifically, sensitivity to violation of the socio-spatial order in urban settings. In previous research, higher scores on the Urban Socio-Spatial Disorder Sensitivity Scale (UDSS), which is composed of two subscales – Space Intrusion (SI) and Place Transgression (PT) – predicted negative feelings towards a target person behaving according to the definition of SI (the unwelcome presence of a certain category of people such as beggars and homeless individuals) and predicted negative emotions toward a person violating norms of behaviors and meanings assigned to a place (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017).

The construct of sociospatial disorder sensitivity is built on Douglas’s (1984) anthropological idea of ‘matter out of place’. Douglas suggests that separation, cleansing, isolating, or suppressing transgression all serve the same purpose: they systematize experience, which is, in its nature, disordered. Douglas’s (1984) assumptions were extended by Bauman (1997), who described a ‘dream of purity’ and focused on how entire social groups have been classified as dirty and contaminated. Addressing the problem of dirt in social reality and using the definition of dirt as an ‘out of place’ object, he shows that the ‘pollution problem’ of the world inhabited by people has appeared quite often. It takes different forms – among others, the form of intrusive neighbors who are regarded as not suitable as neighbors or as not fit for this world. The opposite of purity – impurity, blot, defect, dirt – arises when objects are found in a place unlike the one originally designed for them in the schema of imagined order, in which case actions taken against them, such as deportation, are found to be justified and rational.

People who are sensitive to space intrusion may endorse negative attitudes toward immigrants and refugees in their community since they see them as disruptors of the social order. Humans tend to have a strong need to create their identity based on labels (gender, nationality, etc.), and a change in one of these labels can result in cognitive dissonance and restorative actions. Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), the main premise of which is that a person’s sense of who they are is based on their group membership(s), identifies people’s need to affiliate with a group that is perceived as successful and, by doing so, to improve their self-image by trying to enhance their self-esteem. This process results in in-group favoritism and biased aversion towards the out-group. People who have learned to systematically distrust all outsiders and who associate themselves only with people within their echo chamber base their identity on their membership within a certain group while developing prejudice against members of other groups. Urban disorder sensitivity was found to be related to autochthony and local identification, while autochthony was positively associated with prejudice towards immigrants (Gattino et al., 2019).

Social psychology has proven the existence of a relationship between preferences for various forms of structure (considered to be either a personal trait or a trait activated in a given situation) and prejudice, stereotyping, and depreciation of people from out-groups. These forms of structure include the need for structure (Landau et al., 2004; Schaller et al., 1995), the need for cognitive structure (Bar-Tal & Guinote, 2002), the need for cognitive closure (Roets & Van Hiel, 2011a, 2011b) and sensitivity to the violation of symbolic self-boundaries (Burris & Rempel, 2004).

In this paper, we assume that perceiving a wide range of people as violating the socio-spatial order in the city will be related to a stronger preference for homogeneous social structure. This means that a stronger preference for order, structure, and predictability in the social world, which we think is reflected in the Space Intrusion (SI) subscale of the UDSS, will allow the prediction of more aversive reactions towards the idea of people of another race, ethnicity or religion settling in the neighborhood. Instead of using conventional measures of prejudice, we decided to ask participants about the urban context – first about the neighborhood and then about particular objects in the city. In our opinion, this better reflects the dynamics of relationships and the willingness to meet the outgroup in the city. For this reason, we based our questions on the Social Distance Scale (Bogardus, 1933), adapted to the urban context.

SPACE INTRUSION AND OUTGROUP NEGATIVITY

Space intruders are people who are perceived as not belonging to the place where they are. Their behavior is irrelevant, but generally, although not exclusively, they belong to a stigmatized social group such as beggars or homeless people. A space intruder can be anyone who does not belong to the ‘tribe’. Hence, the appearance of a person who is not an expected or desired user of a given place can be said to violate the socio-spatial order. The term out of place is used interchangeably.

Auestad (2018) defines prejudice as characterized by ‘symbolic transfer’ (transfer of a value-laden meaning onto a socially formed category and then onto individuals who are deemed to belong to that category), resistance to change, and overgeneralization. Overgeneralization and ‘symbolic transfer’ lead to stereotyping and cognitive laziness. Refugees and immigrants are often victims of stereotyping (Bradley-Geist & Schmidtke, 2018; Dimitrova et al., 2017; Murašovs et al., 2016; Riyadi & Widhiasti, 2020). People’s resistance to change in the urban environment may become apparent when the public space becomes occupied by unexpected people, which can violate the safe and predictable physical world of an individual and thus cause anxiety and disrupt the feeling of comfort in the physical world that comes from routines (Burris & Rempel, 2004).

In Study 1A, we would like to show the specificity of the SI construct in relation to right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) and social dominance orientation (SDO). Numerous studies (Asbrock et al., 2010; Duckitt & Sibley, 2007; Jarmakowski-Kostrzanowski & Radkiewicz, 2021; Roccato & Ricolfi, 2005) have shown that RWA and SDO independently predict generalized negativity to out-groups and moral condemnation of harming animals. The dual-process model of prejudice (DPM – Duckitt, 2006) proposes that RWA expresses the motivational goal of group security and order, whereas SDO expresses the motivational goal of group power and dominance. Thus, threatening social situations characterized by high levels of uncertainty may increase authoritarianism. Conversely, social dominance may increase when the social world is seen as a competitive jungle over power and status. Both RWA and SDO are based on worldviews beliefs and are partially context-dependent.

There are some similarities between UDS and RWA. High RWAs are more motivated to protect societal stability and order. High UDS are expected to be more vulnerable to order violation signals in urban settings. RWA is related to more negative attitudes toward social groups perceived as deviant, and the SI subscale of UDS predicted anxiety and contempt toward the unwelcome presence of certain categories of people in urban settings (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017). We assume that similarly to RWA (Jugert et al., 2009), epistemic motives such as the personal need for structure may underlie the UDS construct. However, we expect that compared to RWA, and especially SDO, UDS will be a stronger predictor of environmental distance measured as the extent to which individuals are motivated to avoid interaction with out-groups in urban settings. Our line of reasoning is consistent with the previous work of Newheiser and Dovidio (2012). They found that right-wing authoritarianism and personal need for structure (PNS) differentially predict prejudice and stereotyping. Prejudice was linked to RWA, and stereotyping to PNS. Environmental distance in our study is generally motivated to keep the social world as it is, and we treat it as a different facet of negativity to out-groups than stereotyping and prejudice.

In Study 1B, we also included a sense of community (SOC) and public space concerns. Previous research (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017) showed that social capital bonding and quality of neighborhood ties were inversely related to urban disorder sensitivity; however, the relation between neighborhood characteristics and outgroup negativity has not been tested in this study. As a grounded psychological concept, the theory of SOC has been applied to different groups and contexts. In Study 1B, we analyze SOC with regard to the neighborhood, but it has also been investigated, for example, in the contexts of science classes, e-learning, the religious, the musical, and gay communities (Ng & Fisher, 2016; Rivera-Segarra et al., 2015). McMillan and Chavis (1986) argued that this concept includes four dimensions of community experience: needs fulfillment, membership, influence, and shared emotional connection. The definition of SOC in a neighborhood context focuses on the reciprocal relationship between people and the place-based community (see also Xu et al., 2010 for a broader discussion). Sense of community shares with social identity the component of membership but, on the other hand, reflects the aspects related to the quality of life such as needs fulfillment or emotional connection. The investigations of the relation between SOC and prejudice have produced mixed findings. Prezza et al. (2008) found no relationship between a sense of community and prejudice. Mannarini et al. (2017) observed that the relationship was moderated by perceived heterogeneity: when perceived heterogeneity was low, SOC was negatively associated with prejudice. In the Polish context where the ethnic composition is largely homogeneous, we expected a similar pattern of the results.

In Study 1B we also introduce the public space concern. The interest in the quality of public space is a relatively new phenomenon in Poland. In the public debate, there are threads concerning both aspects related to the state of the physical environment (greenery, air condition) and social aspects (privatization, limited access for some residents). We assume that individuals who express concern for the quality of public space endorse its inclusive nature. Therefore, we expected an inverse relationship between public space concern and environmental distance.

As Reicher et al. (2010) argue, social identity is context-dependent and is responsive to subjectively apprehended features of social reality. We assume that visual cues of out-group membership may play a bridging role between the discomfort associated with the presence of ‘unwanted’ people and a preference to maintain the environmental distance.

OUT-GROUP VISUAL ENCROACHMENT

In this study, we decided to include the concept of out-group visual encroachment to measure potential discomfort related to the perceived visual attributes of strangers. The term out-group encroachment refers to the specific intergroup threat that comes from observing that the minority is getting out of their place and, by doing so, is perceived by the majority as threatening their dominance and power status (Bobo, 1999; Minescu & Poppe, 2011). Research shows that this phenomenon affects social functioning. For instance, Martinovic and Verkuyten (2013) concluded in their study that the level of perceived out-group encroachment mediates the relationship between autochthony and prejudice. Out-group visual encroachment extends the idea of visual dissonance into the urban context.

Visual dissonance is defined as a state of mental tension caused by the experience of a discrepancy between what we anticipated seeing and what we actually see. The concept is related to cognitive dissonance, a well-known phenomenon that occurs when we perceive a discrepancy between our attitudes and our behaviors. According to Festinger (1962), when people experience two actions or ideas that are not psychologically consistent with each other, they do all in their power to change them until they become consistent. Similarly, when people see something/someone disrupting their idea of what a familiar space should look like, they do their best to make sense of the situation and try to protect the cognitive representations of the space that form the building blocks of their identity.

The phenomenon of cognitive dissonance is well-established. Van Veen et al. (2009) identified the neural bases of cognitive dissonance with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), further validating the concept. The occurrence of cognitive dissonance is associated with neural activity in the left frontal cortex, a brain structure also associated with the emotion of anger; additionally, anger motivates neural activity in the left frontal cortex (Harmon-Jones, 2004). The relation between cognitive dissonance and anger is the result of neural activity in the left frontal cortex; when an individual experiences cognitive dissonance, the resulting anger motivates him or her to take control over the social situation that causes the cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, if people are not able to control or change a psychologically stressful situation, or they have no motivation to change the circumstances, other negative emotions arise to handle the cognitive dissonance, such as socially inappropriate behaviors (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Harmon-Jones, 1999).

Based on the available research on cognitive dissonance, we hypothesize that just seeing an outgroup person in a place with which an individual identifies triggers visual dissonance, which leads to negative emotions and feelings towards the person causing the dissonance. Studies conducted by Ratner et al. (2014) demonstrated the degree of automation of cognitive processes. In these studies, depictions of ingroup faces were significantly more likely than depictions of outgroup faces to elicit favorable adjectives (such as trustworthy, caring, intelligent, attractive). In addition, ingroup face representations elicited more favorable implicitly measured attitudes than did outgroup representations, ingroup faces were trusted more than outgroup faces during an economic game, and facial physiognomy associated with trustworthiness more closely resembled the facial structure of the average ingroup than outgroup face representation.

AIMS AND HYPOTHESIS

The main goal of the present studies was to test the relationship between urban disorder sensitivity and willingness to interact with other group members in the urban context. The research hypotheses were thus as follows: 1) urban socio-spatial disorder sensitivity in the social aspect (Space Intrusion subscale) will predict a lower acceptance of outgroups residing in one’s neighborhood (pilot study); 2) the relationship between urban socio-spatial disorder in the social aspect and environmental distance will be mediated by out-group visual encroachment (Study 1A and Study 1B). Additionally, in Study 1A, we decided to add to the model other variables strongly related to out-group prejudice, namely, authoritarianism and social dominance orientation (SDO). In Study 1B, we also included measures related to social capital and human-place bonds.

PILOT STUDY

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

During the construction and initial validation of the Urban Disorder Sensitivity Scale (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017), we used the scale to measure the acceptance of the presence of out-groups in the neighborhood.

Five hundred and six participants (68.8% women) completed the online survey. The participants were students from the University of Gdańsk, and other adults recruited by them. Students received points in return for participation and recruitment. Most of the participants inhabited the Tri-City agglomeration (n = 484). The mean age of participants was 23.68 (SD = 6.63). Most of them (80.4%) were young, in the range of 18-24 years. 17% were in the 25-44 age range, and 2.6% were above 45 years.

MEASURES

The following scales were used:

The Urban Disorder Sensitivity Scale (UDSS; Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017), which consists of 12 items rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Six items (e.g. “I would get nervous seeing a person sleeping on a park bench”) belong to the Space Intrusion (SI) subscale. The other six (e.g. “I feel disturbed when I think that local authorities sometimes allow spray paint in underground tunnels”) belong to the Place Transgression (PT) subscale. Cronbach’s α was .79 for SI, and .64 for PT.

Acceptance of outgroup members was measured by three items with Cronbach’s α = .84 (e.g. “I would like people of other races to settle in my neighborhood” and “I would like people of other cultures to settle in my neighborhood”) with a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The Relations with Neighbors Scale (Lewicka, 2005) (e.g. “I know my neighbors only by sight”). Participants responded on a 5-point scale (Cronbach’s α = .88) anchored by 1 (none) and 5 (almost everyone).

The Social Capital Scale (Lewicka, 2012) includes two subscales: bonding (e.g. “Do you know anyone who could take care of you when you are ill?”) and bridging (e.g. “Do you know a person with whom you have a friendship you can brag about?”). Participants responded on a 4-point scale anchored by 1 (I don’t know) and 4 (I know very well). Cronbach’s α was .83.

The Identity Fusion Scale, which consists of seven items based on a scale by Gomez et al. (2011; see also Besta et al., 2014), was adapted to measure the overlap between personal and city identity (α = .94), with items such as “My city is me”.

The Group Identification Scale, which comprises six items measuring group identification in the context of a city (α = .91), was adapted from Mael and Ashforth (1992), with items such as “When someone criticizes my city, it feels like a personal insult” and “I am very interested in what others think about my city”.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To determine whether socio-spatial disorder sensitivity was a significant predictor of acceptance towards immigrants in one’s neighborhood, we conducted a multiple regression analysis. In the first step, we entered demographic variables, in the second step variables related to the quality of social relations (bonding and bridging social capital and the quality of neighborhood ties) and measures related to the centrality of the city in self-concept (fusion and identification), and in the third step the UDSS subscales. Consistent with our hypothesis, the score on the SI subscale of the UDSS was only associated with reluctance to live in close vicinity to outgroups in one’s neighborhood (β = .19, p < .001) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Summary of stepwise multiple regression for the variable: reluctance to live in close vicinity to outgroup members

In this study, we found initial evidence for a link between the SI subscale score and acceptance of out-groups in one’s neighborhood. The SI subscale reflects discomfort with the presence of certain categories of people, usually belonging to stigmatized groups who are perceived as violating the sociospatial order. This study confirmed that out-groups such as immigrants and refugees are also more likely to be perceived as ‘out of place’ in the neighborhood by people who tend to perceive urban social reality through categories of (de)legitimized users of space.

STUDIES 1A AND 1B

OVERVIEW

As we assumed, perception of space intrusion is based on visual signals that an individual belongs to certain social categories, giving rise to the perceiver feeling threatened. Therefore, in Studies 1A and 1B, we tested the role of a possible mediator – outgroup visual encroachment, that is, the degree to which individuals feel discomfort with visual cues that individuals belong to minority groups. In Studies 1A and 1B, we decided to focus on environmental distancing from Muslims. In the Polish public debate around immigration and refugee issues, Muslims have sometimes been stigmatized and portrayed as a threat to the social order. In Study 1A, we also included authoritarianism and social dominance orientation as predictors of generalized prejudice. In Study 1B, we included public space concerns of the majority of the community and relationships with neighbors. Public space concern reflects concerns about the quality and condition of public space, where typical problems are noise, air pollution, lack of greenery, poor aesthetics, and visual chaos generated by advertisements. We expected that individuals who were more concerned about public space, which by definition should be equally accessible to all, would be less likely to maintain environmental distance toward Muslims. A similar pattern was expected for a sense of community and relationships with neighbors. Both constructs reflect the state of being strongly rooted in one’s place, which we expected would be related inversely to environmental distance toward others because of the low heterogeneity of Polish neighborhoods (Mannarini et al., 2017). Previous research showed that better access to social capital as well as closer relations with one’s neighbors was a predictor of lower urban disorder sensitivity (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017).

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

In Study 1A, 108 (89 women) students at the University of Gdańsk (M = 21.92, SD = 2.69) completed a questionnaire (paper/pencil method). In Study 1B, 162 participants (95 women, M = 28.65, SD = 9.45) were recruited from among students to complete an online questionnaire. Students received points in return for participation in the study.

MEASURES

Urban disorder sensitivity. The same 12-item scale used in the pilot study was used in Studies 1A and 1B. Cronbach’s α was .72, and .74 for the SI subscale, .66, and .64 for the PT subscale.

Out-group visual encroachment. The 4-item scale was constructed to measure discomfort related to visual cues signaling members of an out-group: “I believe that the image of other group members is at odds with the landscape of Polish cities”; “I don’t like it when other group members show their group differences on the street”; “I feel discomfort when members of ethnic groups wear their traditional clothes on the street”; and “I believe that immigrants should adapt their appearance to that of the majority”. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely disagree) to 7 (definitely agree). The scale’s Cronbach’s α was .87 in Study 1A and .83 in Study 1B.

Environmental distance. In Study 1A, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they would like to meet a Muslim in places such as a grocery shop, barbershop, drug store, bakery, restaurant/pub, and bus/tram stop (Cronbach’s α = .95). In Study 1B, the bus/tram stop item was removed (Cronbach’s α = .98). In both studies, participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely not) to 7 (definitely yes). The scale was reverse coded to measure environmental distance, so the higher scores indicated a greater preference for avoiding contact.

Additionally, the following scales were used only in Study 1A:

Authoritarianism. The scale of authoritarianism (Korzeniowski, 2009) consists of nine items (e.g. “The most important thing to teach children is complete obedience to their parents” and “There must be something wrong with non-believers in God”). Respondents used a 7-point Likert response format (Cronbach’s α = .76).

Social dominance orientation (SDO). SDO was measured using a 16-item scale (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999; see Klebaniuk, 2009 for the Polish version). Respondents used a 7-point Likert response format (Cronbach’s α = .90).

City identification. We used a six-item scale to measure group identification (Mael & Ashforth, 1992), adapted to the context of the city (see Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2014 for previous use). Items included “When someone criticizes my city, it feels like a personal insult” and “I am very interested in what others think about my city”. Cronbach’s α of the scale was .84.

In Study 1B we used:

Relations with neighbors. Participants assessed their relationships with neighbors by answering two questions using a 7-point Likert scale: “How strong would your relations with neighbors be if you lived in the described neighborhood?” (1 – very weak, 7 – very strong) and “How many kind and helpful neighbors do you have in your neighborhood?” (1 – none, 7 – many). The scale was previously used by Jaśkiewicz and Wiwatowska (2018).

Sense of community. We assessed participants’ sense of community by using a Polish translation of the eight-item Brief Sense of Community Scale (Peterson et al., 2007). Participants responded to statements about their neighborhood (Cronbach’s α = .84), for example, “This neighborhood would help me fulfill my needs” and “I would belong to this neighborhood”.

Public space concerns. The extent of concern about public space was measured by a 7-item scale (Cronbach’s α = .76) with items such as noise, outdoor advertisement overloading, lack of greenery, and visual chaos. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (it does not evoke any concern at all) to 7 (it evokes strong concern).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In both studies, we conducted linear regression analysis with environmental distance toward Muslims as the explained variable. As we expected, urban disorder sensitivity in social aspects (Space Intrusion) turned out to be a significant predictor in Study 1A (β = .19, p = .039). However, in Study 1B, SI was only of borderline significance (β = .15, p = .056). In both studies, out-group visual encroachment was the strongest predictor of environmental distance (β = .48 and β = .49, respectively). Surprisingly, neither authoritarianism nor social dominance orientation (SDO) predicted environmental distance (see Table 2).

Table 2

Summary of multiple regression for the variable: environmental distance toward Muslims, Study 1A

The other significant predictors were gender (Study 1A), sense of community, and public space concern (Study 1B) (see Table 3).

Table 3

Summary of multiple regression for the variable: environmental distance toward Muslims, Study 1B

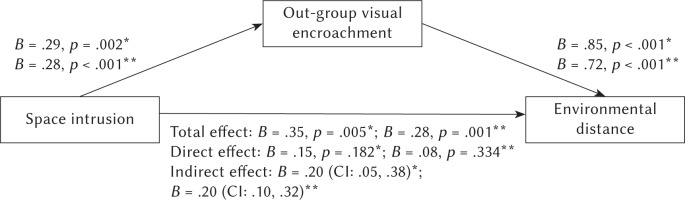

In both studies, we tested the indirect effect with the PROCESS macro, model 4 (Hayes, 2013). We put environmental distance into the model as the outcome variable, out-group visual encroachment as the mediator, and SI as the predictor. In both studies, an indirect effect for out-group visual encroachment was found to be significant with confidence intervals not including zero (.05, .38, and .10, .32, respectively). As we expected, space intrusion predicted out-group visual encroachment, and out-group visual encroachment was related to environmental distance (see Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The results of these studies provide support for our hypotheses. Urban disorder sensitivity in a social domain was linked to lower acceptance of strangers in one’s neighborhood. Moreover, we found that the relation between urban disorder sensitivity and maintaining environmental distance was mediated by out-group visual encroachment, that is, the tendency to perceive others as not ‘fitting in’ based on their visual characteristics. The fact that the results showed that UDS was a unique predictor of environmental distance when we put SDO and RWA into the model indicates that they measure different constructs. We assume that UDS is more similar to RWA than SDO by having at its base the need for a structure and predictability. However, there are also some differences: RWA is associated with obedience and submission, and UDS is not. Finally, UDS is more focused on the urban context.

The classical idea presented by Douglas (1984) clearly links the idea of social things and objects that are ‘out of place’ with the desire to create order. As such, the relationship between urban socio-spatial disorder sensitivity and lower acceptance of immigrants in one’s neighborhood seems to be quite obvious and well-founded in the theoretical assumptions underlying the construction of the Urban Disorder Sensitivity Scale (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2017). Similarly, numerous studies in social psychology illustrate that prejudice, stereotypes, or a heightened need to structure the social world can be motivated by a need to avoid chaos and uncertainty and to make sense of and to give meaning to reality (Dechesne & Kruglanski, 2004; Heine et al., 2006; Jost et al., 2003; Landau et al., 2004).

In the present studies, we focused on linking outgroup negativity with issues of place, space, and environment. As Reicher et al. (2010) posit, social identity not only gives people a sense of belonging but also provides a sense of where they belong. Reicher et al. (2006) link the notion of ‘belonging’ with a sense of ‘fitting in’ to the location. This ‘fitting in’ includes sharing local practices, being accepted by others, and being able to maintain one’s identity-related values and actions. We can easily imagine the perception that ‘others’ do not ‘fit in’ based on their visual characteristics. In the light of the present studies, this perception is related to the broader tendency to be vulnerable to social objects that disrupt the imagined and preferable social order. We think that visual cues that individuals in one’s neighborhood belong to an out-group may threaten the familiar world, way of life, and routinized modes of action. In this context, maintaining environmental distance may be interpreted as regulation of spatial behavior to keep the local social world as it is.

In a similar vein, Wnuk et al. (2021) recently found that perceiving out-groups as fitting into a place and being more open to social diversity is related to the anti-essentialist view of the place. The stable essence of a place could be seen as incompatible with belonging to the place’s various social groups. In this approach, a place can have inherent meaning reflected in the essential attributes that many people are able to perceive. We assume that characteristics of the individual related to his or her direct perception or sensory experience may also interact with environmental features. People who score high on the urban disorder sensitivity scale are probably more vulnerable to environmental features signaling the presence of out-groups in their place perception. In this case, the sensory dimension of sight contributes to maintaining the existing meanings of a place that do not include people who belong to other social groups. Therefore, combining the contribution of individual characteristics, sensory perception, and environmental features, we are inclined to a more dynamic approach to the sense of place, which has also been postulated by Raymond et al. (2017). They argued that meanings ascribed to place are rarely considered as a joint product of environmental features and attributes of the individual, and we hope that our study partially fills this gap.

In our studies (pilot study and Study 1A), we found gender differences with regard to outgroup negativity, with men endorsing more negative attitudes. As the study was conducted mainly on young people, this confirms the earlier results showing that young men in Poland are more conservative and display stronger prejudices than young women (Pacewicz, 2019).

The debate on the state of public space is inextricably linked with the issue of the presence of outgroup members in it. In our study, public space concern was associated negatively with environmental distance. This is probably related to the fact that in the Polish debate issues such as noise, lack of green areas, and low levels of aesthetics are usually associated with a more progressive and inclusive worldview.

We also found, at the borderline significance level, an inverse relationship between sense of community and environmental distance. Although we can expect, similarly to Mannarini et al. (2017), that this relationship may be moderated by perceived heterogeneity of the neighborhood, further studies should address this issue directly in the Polish context.

Finally, this study raises the question of whether there are environmental signals that support openness to diversity. Rietveld et al. (2017) posit that a familiar social environment is a source of regularity and meaning in the world. They point out that increased heterogeneity of the population may undermine the familiarity of strangers and the certainties of socio-cultural practices. We assume that these uncertainties are reflected in the urban disorder sensitivity construct. Rietveld et al. (2017) raised the very important issue of how shaping the public domain increases the chance for ‘others’ to become ‘trusted familiar strangers’. The public domain is understood as a place where people from different socio-cultural groups can meet (Hajer & Reijndorp, 2001). As they argued, the constructed environment may invite visitors to explore the place and to engage in some activities (e.g. around the campfire). Most important in the light of the present studies, Rietveld et al. (2017) emphasize the potential for observation and being observed in well-designed public spaces. This natural interest in others and the possibility of observing them would give us the possibility of not perceiving them as being ‘out of place’ but rather as ‘trusted familiar strangers’.

LIMITATIONS

Our studies have several limitations. The correlational nature of studies does not indicate a causal relationship. More women participated in the studies, whereas we can expect gender differences with regard to prejudice or SDO. Although the urban disorder sensitivity measure is generally related to the urban context, future research should take better account of the specific contexts. We conduct our research mainly among inhabitants of Gdansk, Poland, where despite the multi-cultural tradition (Jaśkiewicz et al., 2021), the society is ethnically homogeneous. We chose Muslims as the target group because Islamophobia represents an important form of contemporary outgroup bias in Poland, but Ukrainians constitute the largest group of immigrants. Finally, increasing the ecological validity of the study could be achieved by analyzing specific urban spaces, such as streets or parks, and the spatial behavior of their users.