BACKGROUND

Attachment style is one important predictor of self-related outcomes (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). A growing literature has begun to explore factors contributing to explaining the mechanisms underlying the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity (Emery et al., 2018; Kawamoto, 2020; Wu, 2009; Yang & Oshio, 2024), and the extent to which the content of an individual’s self-concept is clearly and confidently defined (Campbell et al., 1996). Self-concept clarity plays an important role in promoting life satisfaction and personal meaning (Yuliawati et al., 2024). However, existing literature on the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity is limited to an individual perspective. The current study aimed to explore the following novel questions: Does an individual’s attachment style impact the partner’s self-concept clarity? If so, can mindfulness explain at least part of this process?

ATTACHMENT SECURITY AND SELF-CONCEPT CLARITY

Attachment style in adulthood refers to the way individuals emotionally bond with others, particularly in the context of intimate relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). The concept is often measured using two dimensions: attachment avoidance and anxiety (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley et al., 2015; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016, 2023). The latter represents the extent to which one feels uncomfortable with closeness and intimacy, while the former refers to being consistently worried about being abandoned (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Attachment style is linked to self-concept clarity, such that a secure attachment may contribute to a higher level of self-concept clarity, and an insecure one may decrease one’s self-concept clarity. The two insecure dimensions play different roles in this process. People with high attachment anxiety tend to adopt activating strategies, focusing on others instead of themselves and taking more immediate actions instead of thinking it deliberately (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Being unaware of their own feelings and behaviors, anxiously attached people are thus likely to lack information about themselves that is required for forming clear and stable self-knowledge. As for avoidantly attached people, they tend to utilize de-activating strategies, keeping their distance from others and emphasizing their independence (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). This may cause problems in forming self-concept clarity because they lack the opportunity to receive feedback from others, which is an important resource for self-knowledge. Consistent with attachment theory, Wu (2009) first empirically examined the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity. Two cross-sectional studies were conducted (Wu, 2009), revealing that only attachment anxiety had a unique effect in predicting self-concept clarity when controlling for the other attachment dimensions. Likewise, Kawamoto (2020) found a positive association between self-esteem and self-concept clarity only among those low in attachment anxiety. Across five studies, Emery et al. (2018) focused on the attachment avoidance dimension and found that avoidant individuals’ reluctance to trust or become too close to others may result in hidden costs to the self-concept. More recently, Yang and Oshio (2024) used cross-sectional and online priming designs and found that anxiously attached people may lack awareness of their own behaviors, leading to lower self-concept clarity. These observations support the idea that attachment style impacts self-concept clarity, and further, the dimension of attachment anxiety plays a more important role than avoidance in self-concept clarity. However, there is currently a lack of research on the relationship between attachment style, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity within the context of romantic relationships. That is, does one’s attachment style impact one’s partner’s self-concept clarity? This issue is particularly important given the theoretical emphasis of adult attachment theory in romantic relationships, which has proposed the importance of how one’s attachment style plays a role in one’s development (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Sagone et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2021). Understanding how attachment styles influence partners’ self-concept clarity may contribute to the attachment literature by providing insights into how an individual’s attachment style can impact their partners. Since attachment style represents the way that one interacts with one’s partner, and the behaviors and feedback from others are important resources for self-concept clarity, we predicted that attachment style will be associated with self-concept clarity. More specifically, anxiously attached people may provide their partner with more ambivalent information due to their hyper-activating strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016) and relatively unstable emotions (Noftle & Shaver, 2006). As for avoidantly attached people, since they tend to keep their distance from their partner, their partner will receive less information from them. However, previous studies consistently found that men rely on their romantic partners more than women do, and when in a romantic relationship, men perceive greater social support compared to women (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Stronge et al., 2019). In the same way, men may rely more solely on their romantic partners for information to form self-concept clarity. Instead, women may have more social support and resources for self-concept clarity. Thus, we expected that attachment anxiety would play a more important role in predicting self-concept clarity than attachment avoidance, and this effect would be more evident for men than women.

THE MEDIATING ROLE OF MINDFULNESS

Beyond the feedback from partners, which has been emphasized by previous research (Emery et al., 2018), attachment style also plays a role in the way people treat their experiences (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016) and thus impacts an individual’s own and their partner’s self-concept clarity. Mindfulness refers to an open and nonjudging awareness toward one’s moment-to-moment experiences (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Bunjak et al., 2022). Previous research has found that mindfulness is important to the relationship’s quality and conflict resolution strategies (Mandal & Lip, 2022). Bishop et al. (2004) proposed a two-component model of mindfulness, which includes the self-regulation of attention and orientation to experience. They further predicted that the stance of curiosity and acceptance during mindfulness practices would lead to decreases in the use of cognitive and behavioral strategies to avoid aspects of experience, increases in openness, and changes in the psychological context in which those objects are now experienced (Bishop et al., 2004).

There is a wealth of studies that have established the relationship between attachment style and mindfulness (Stevenson et al., 2017, 2021), suggesting that securely attached people tend to treat their feelings and thoughts mindfully. This relationship may suggest that a peaceful and stable internal and external environment may benefit the cultivation of mindfulness. For example, previous research has found that detachment from work, sleep quality, and workload were related to subsequent levels of mindfulness (Hülsheger et al., 2018). In a similar way, the frequent and exaggerated negative emotions of anxiously attached people not only hinder achievement of their own mindfulness but also disrupt their partner’s mindfulness. Empirically, mindfulness, especially the acting with awareness component, was found to be a mediator in the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity (Yang & Oshio, 2024). Compared to the attachment security condition, when priming attachment anxiety, participants reported significantly lower levels of mindfulness, which further predicted lower levels of self-concept clarity (Yang & Oshio, 2024). As for attachment avoidance, it may also impact one’s partner’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity due to their lack of communication (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Schrage et al., 2020). However, the impact of one’s attachment avoidance on one’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity (Kawamoto, 2020; Wu, 2009; Yang & Oshio, 2024) has been found to be relatively small. Therefore, at an individual level, we hypothesized that one’s attachment style, especially attachment anxiety, is negatively associated with one’s self-concept clarity, and one’s mindfulness plays a mediating role in this association. Moreover, individuals with anxious attachment often seek extensive emotional support from their partners, which can lead to partner burnout (Girme et al., 2021). This constant demand for reassurance and emotional closeness can create significant stress and emotional fatigue for the partner. Over time, this strain may deplete the partner’s emotional resources, making it difficult for them to remain mindful and present in the relationship. Consequently, it could also be difficult for anxiously attached individuals’ partners to remain mindful. Thus, at a dyadic level, we also expected one’s attachment anxiety to be negatively associated with one’s partner’s mindfulness, which will further lead to an impact on one’s partner’s self-concept. The impacts from women to men were supposed to be larger than the reverse direction. Moreover, we predicted that the impact of one’s attachment avoidance on one’s partner’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity, if any, would be less than attachment anxiety.

To sum up, the primary aim of the current investigation was to explore the mediating effect of mindfulness in the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity within a dyadic context. To this end, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of married couples in China.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The current study employed a convenience sampling method and surveyed parents from a primary school in Chengdu through an online questionnaire platform (www.wenjuan.com). A total of 1512 questionnaires were collected from wives and 1294 from husbands. Three hundred and sixty-one families had one child, 395 families had two children, and 17 families had three or more children. During the questionnaire completion process, three attention check questions were set (e.g., “This question is an attention check, please select strongly agree”; Ward & Meade, 2023). A total of 331 wives and 288 husbands failed one or more of the attention check questions. After excluding single parents, a final sample of 773 pairs of heterosexual married couples was obtained (Mage = 35.43, SDage = 3.77 for wives; Mage = 37.46, SDage = 4.39 for husbands). All participants signed an informed consent form before filling out the questionnaire and received a certain remuneration upon completion of the study. The Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University approved all contents of the present study.

MEASURES

Attachment style. We utilized the nine-item Chinese version of the Experience in Close Relationship-Relationship Structure (ECR-RS; Fraley et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2022) to measure attachment avoidance and anxiety. The participants were required to answer the ECR-RS based on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). ECR-RS includes two dimensions: attachment avoidance (e.g., “I prefer not to show my dating partner how I feel deep down”) and attachment anxiety (e.g., “I worry that my dating partner will not care about me as much as I care about him or her”). A higher total score represents a higher level of attachment anxiety and avoidance. Cronbach’s α values in the present study are presented in Table S1 (see Supplementary materials).

Mindfulness. Mindfulness was measured by a 15-item short form of the Chinese version of the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ-SF-C; Zhu et al., 2021) based on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items are, “When I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”, “I’m good at finding the words to describe my feelings”, “When I do things, my mind wanders off, and I’m easily distracted”, “I think some of my emotions are bad or inappropriate and I shouldn’t feel them”, and “In difficult situations, I can pause without immediately reacting”. Higher total scores indicate a higher degree of mindfulness. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .79 for the FFMQ-SF-C.

Self-concept clarity. We used the Chinese version of the 12-item Self-Concept Clarity Scale for self-concept clarity (e.g., “My beliefs about myself often conflict with one another”) (Campbell et al., 1996; Wu & Watkins, 2009). Responses to the scale were made on a seven-point Likert scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). The scale was scored in such a way that a higher total score means a higher level of self-concept clarity. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .84 for this scale.

DATA ANALYSES

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 28 and Mplus Version 8.8. Because all data in the current study were collected through self-report measurements, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to examine the common method bias before the data analysis (Podsakoff et al., 2003). All subscales of attachment style, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity were subjected to exploratory analysis, and the unrotated factor solution was examined to determine the number of factors that are necessary to account for the overall variance. After descriptive analyses, the current study used the Actor-Partner Interdependence Mediation Models (APIMeMs; Ledermann et al., 2011) to examine the actor, partner, and mediation effects. This analysis followed the procedure proposed by Ledermann et al. (2011), constructing a mediation model with eight actor effects and eight partner effects and then assessing the direct and indirect effects by bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with 5000 bootstrap draws. Actor effects describe the relationship between one’s attachment style, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity. Partner effects describe the relationship between one’s attachment style and mindfulness and one’s partner’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity.

RESULTS

Harman’s single-factor test suggested that there was no single factor that accounted for most of the covariance among the variables (Factor 1 accounted for 16.70% of the covariance). As shown in Table S1 (see Supplementary materials) the Cronbach alphas, M, SD, and correlations were calculated for each variable included in the current study. All measures demonstrated acceptable reliabilities that were consistent with previous studies (Wu & Watkins, 2009; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2021), as indicated by their Cronbach’s α values. Both attachment avoidance and anxiety significantly and negatively correlated with mindfulness and self-concept clarity, which was consistently observed in both the women and men samples. There was a positive correlation between mindfulness and self-concept clarity, both in women and men samples.

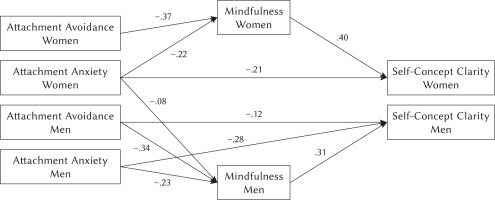

Table 1 shows the results of the actor-partner interdependence mediation modeling. Within both the female and male groups, one’s attachment avoidance and anxiety significantly predicted one’s mindfulness levels. Furthermore, one’s mindfulness level was found to be significantly predictive of one’s self-concept clarity. These observations indicated actor effects of attachment avoidance and anxiety on mindfulness as well as mindfulness on self-concept clarity. Moreover, within the women sample, one’s attachment anxiety significantly predicted one’s self-concept clarity. However, both one’s attachment avoidance and anxiety significantly predicted one’s self-concept clarity in the sample of men. Regarding partner effects, only women’s attachment anxiety significantly predicted men’s mindfulness. To test the mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between attachment avoidance, attachment anxiety, and self-concept clarity, a bootstrap method with 5000 resamples was employed for the analysis (Table 2). The mediating model of actor effects was significant, such that for women and men, one’s mindfulness mediated the relationship between one’s attachment avoidance and self-concept clarity, as well as attachment anxiety and self-concept clarity. As for the partner effect, women’s attachment anxiety was negatively associated with men’s mindfulness, leading to men’s lower self-concept clarity. An overall model illustrating the mediating role of mindfulness can be found in Figure 1.

Table 1

The actor-partner interdependence mediation model (N = 773)

DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to explore the relationship between attachment style, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity within a dyadic context. We proposed that mindfulness is a mediator in the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity, not only for individuals but also at a dyadic level. Supporting our hypotheses, our results replicated findings from previous research indicating that mindfulness is a mediator in the relationship between attachment style (both avoidance and anxiety) and self-concept clarity for individuals (Emery et al., 2018; Wu, 2009; Yang & Oshio, 2024). Moreover, our research extended previous studies by finding that the attachment anxiety of women negatively predicted the mindfulness of men, which further led to an impact on the self-concept clarity of men. These observations are also consistent with our predictions that the impact of women’s attachment anxiety on men’s self-concept clarity would be greater than that of men’s attachment anxiety and avoidance and women’s attachment avoidance.

The current study provided new insights into the relationship between attachment style, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity. Our findings provide preliminary evidence for the idea that the cultivation of mindfulness may require a relatively peaceful and stable environment, both internal and external. For anxiously attached individuals (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), an internal environment filled with worries and negative emotions may make it challenging to be mindful. Within a dyadic context, men may rely more solely on their romantic partners than women (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Stronge et al., 2019). Thus, negative emotions and ambivalent feedback from wives with high attachment anxiety may pose a challenging external environment for men to cultivate mindful awareness and attitude. An anxious attachment will not only create a nervous and unstable internal environment but also provide a burdensome external environment for their partners. Moreover, their hyper-activating strategies may provide more inconsistent information to their partners (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). This kind of environment might lead to more difficulties for both oneself and one’s partner in experiencing mindfulness. Consequently, both may lose opportunities to efficiently utilize internal and external information to cultivate self-concept clarity. Thus, the lack of mindfulness could at least partly explain the negative impact of attachment anxiety on self-concept clarity in a dyadic context. However, only wives’ attachment anxiety was associated with husbands’ mindfulness and self-concept clarity. As mentioned above, this may be explained by the previous finding that men rely more on their romantic partners than women do and that wives may express their anxiety and worries in a more direct way than husbands (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Stronge et al., 2019). Therefore, anxiously attached wives may provide a more anxious and unstable environment than anxiously attached husbands. Nonetheless, these explanations are exploratory and were not examined in the current study, requiring future studies to test their validity.

Table 2

Mediating effects (N = 773)

Figure 1

The actor-partner interdependence mediation model

Note. Only significant paths of the saturated model are presented here for simplicity. Correlations and errors are also omitted. Please see the complete parameters in Table 2.

The negative relationship between attachment avoidance and self-concept clarity was significant at the individual level, but not the dyadic level. That is, there was no statistically significant association between one’s attachment avoidance and one’s partner’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity. Considering their de-activating strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), this may be because, unlike attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance works in a more muted way. When interacting with an avoidantly attached partner, an individual may not express much anxious and ambivalent information which could potentially make their partner stressed or confused. As such, attachment avoidance may not seriously hamper one’s partner’s mindfulness and self-concept clarity. This suggests that no information might be more helpful than providing ambivalent information for partners to cultivate a stable and consistent self-concept.

In collectivist cultures, individuals are more likely to prioritize group harmony and relational interdependence over personal goals, which may enhance the relational focus of attachment styles (Selcuk et al., 2024). This may explain why attachment anxiety, which involves heightened sensitivity to relational dynamics, has a significant impact on self-concept clarity within romantic relationships. In contrast, Western cultures emphasizing individualism, autonomy, and personal achievement may lead to different manifestations of attachment styles and their effects on mindfulness and self-concept clarity (Selcuk et al., 2024), which remain future studies to explore.

There are several limitations in the current study. First, a cross-sectional design cannot determine the directionality among variables. Future research may benefit from using cross-lagged models or experimental methods to rule out alternative explanations. For instance, it may be due to the low self-concept clarity of husbands that makes their wives tend to feel worried about being abandoned, and mindless husbands may cause wives’ attachment anxiety. Second, all variables included in the current study were measured in a self-report manner, which might suffer from self-report bias. To overcome this shortage, future studies need to replicate our findings with various methods, such as partner-report measures and actual behaviors. Moreover, our hypotheses were examined only in a Chinese sample. We expect that our result regarding attachment, mindfulness, and self-concept clarity within a dyadic context could be generalized to populations from different countries and cultures in the future. Third, future studies should consider including homosexual couples to explore whether the observed patterns hold across various types of relationships. In addition, future research should also investigate potential moderator variables, such as cultural background, socio-economic status, and relationship duration, to understand how these factors might influence the observed relationships.

Despite these limitations, the current study provided preliminary evidence for extending the relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity to a dyadic level. We found that one’s mindfulness significantly mediated the relationship between one’s attachment style and self-concept clarity for both women and men. Furthermore, as regards the partner effect, the mindfulness of men significantly mediated the relationship between the attachment anxiety of women and the self-concept clarity of men. Mindfulness may not only serve as a mechanism through which attachment style influences personal outcomes, but it could also be a pivotal factor in understanding the interpersonal effects of attachment style. These findings also have practical implications. The impact of insecure attachment on self-knowledge can be reduced by intervening in individuals’ mindfulness in future intervention activities, and such mindfulness-oriented temporal intervention activities could also work in dyadic situations. Therapists can also help couples create a supportive environment that fosters the cultivation of mindfulness. Encouraging practices that promote emotional safety and stability within the relationship may enhance relational well-being.

Supplementary materials are available on the journal’s website.