BACKGROUND

The free expression of ideas, judgments and opinions opens up the possibility of sharing knowledge and at the same time constitutes the essence of regulating relations in a democratic society (Bar-Tal et al., 2017; Gilligan, 2006). Sharing knowledge in an organization, giving feedback, pointing to problems and suggesting solutions constitute communication aimed at continuous development, based on the predetermined goals and standards (Tushman & Nadler, 1978; Wiener, 1950). This desirable process of open communication clashes with the informal side of social life in an organization, often taking the form of a game in which some win at the expense of others (Argyris & Schon, 1978). As a result, communication openness which is beneficial to the process of achieving organizational goals may be undesirable from the perspective of the interests of the individual who censors his or her own speech (Adamska, 2017). That leads to employee silence (Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Morrison, 2014; Knoll et al., 2016).

Self-censorship protects against the alleged consequences of open communication, but concerns about speaking are not the only reason why an employee remains silent (Zill et al., 2020). When attempts to share information about irregularities observed or about proposals for change end in failure, an employee may become convinced that speaking out is pointless. Both the fear of the consequences of taking the floor and a lack of belief in the sense of taking the floor in the first place are based on experiences derived from direct contact with a superior, HR department, senior superior or colleague. By observing behaviors of others, an employee assimilates informal rules of behaviors, among them the rules of speaking: when, what and with whom (Detert & Edmondson 2011; Knoll et al., 2021; Nechanska et al., 2020). While the social rules of speaking are reflected in employee silence beliefs (Adamska & Retowski, 2012), the individual experiences lead to self-censorship (Knoll & van Dick, 2013).

There are at least two ways of limiting self-censorship: formal, through fair procedures; and informal, through direct influence in the acts of communication (Wilkinson & Dundon, 2017). These two factors are rooted in two different kinds of ethics which are ethics of justice and relational ethics. The ethics of justice is impartial and free from the impact of current circumstances (Rawls, 1999). The relational ethics is contextual and underlines the role that emotions play in moral judgments and decisions (Gilligan, 1982; Hamington, 2019). Studies of factors that limit self-censorship in organizations have been conducted separately for formal procedures (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008) and quality of relations (Gao et al., 2011; Hirak et al., 2012). However, as the reflection on the ethics of justice and relational ethics shows (Allen, 2013), two factors can be mutually complementary in their influence on self-censorship. In organizational studies ethics of justice is represented by procedural justice while relational ethics is represented by interpersonal justice (Colquitt, 2001).

The aim of the research presented in the article is to establish the relationship between procedural justice and employee self-censorship and to assess the importance of interpersonal justice as regards the negative effect of procedural justice on employee self-censorship. Three hypotheses were formulated: Hypothesis 1: Procedural justice predicts a reduction in employee self-censorship; Hypothesis 2: The reduction of employee self-censorship under the influence of procedural justice increases in high interpersonal justice conditions, and Hypothesis 3: The reduction of employee silence beliefs under the influence of procedural justice increases under conditions of high interpersonal justice. Both the decision to remain silent (self-censorship) and the belief that no climate exists for speaking (employee silence beliefs) are associated with a fear of the consequences of speaking or doubt over the effectiveness of speaking (acquiescent and quiescent silence).

SELF-CENSORSHIP AND EMPLOYEE SILENCE BELIEFS

Self-censorship is a strategy developed for coping with others. The belief that ‘it is better to be silent’ may have its roots in early childhood, when the idea of voice is vaguely identified as activity and influence. Punishment for being ‘too visible – too loud’ or failure to receive a response to that voice bolsters this belief. Silence may demonstrate its strategic value in organizations, where the decision to withdraw from voicing in situations perceived as ripe for change for moral or pragmatic reasons (with no formal obstacles to voice) may be shaped by organizational experiences (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). Self-censorship, a kind of deactivation (Pinder & Harlos, 2001), is exacerbated by individual characteristics such as neuroticism or agreeableness (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001), relations between managers and subordinates, or employer-employee relations (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). In the long run, self-censorship has a detrimental effect on individual well-being (Beer & Eisenstat, 2000; Tahmasebi et al., 2013) and may damage group efficiency (Cortina & Magley, 2003; Perlow & Williams, 2003).

There are at least two causes of self-censorship, understood as non-participation: resignation and fear of consequences. Resignation occurs when the employee’s voice goes unanswered, since there is no one, particularly no powerholders, to listen, and all endeavors to gain influence on a critically perceived situation prove futile. This kind of decision to self-censor leads to acquiescent silence, that is passive acceptance of the status quo (Pinder & Harlos, 2001). As a result an employee does not consider alternatives to the current situation. When self-censorship is motivated by fear that voicing may provoke negative responses in recipients, then it takes the form of quiescent silence (Van Dyne et al., 2003). In this case the decision not to speak up is defensive in its character, proactive and consciously driven due to the fact of consideration of negative outcomes. The process of making a decision not to speak is accompanied by negative emotions, which are rooted in childhood experiences with authority (Kish-Gephart et al., 2009) and related to generalized reluctance to deliver negative news to others (Lee, 1993).

Unlike self-censorship, which is a decision by employees to refrain from expressing opinions, criticism or suggestions in situations of perceived irregularities, silence beliefs reflect informal rules of speaking assimilated by a person in an organization in the process of learning effective tactics of communication (particularly in the first stage of employment) (Argyris & Schon, 1978). By observing social incidents an employee recognizes those social settings in which speaking up is futile (acquiescent silence beliefs) and those in which speaking threatens one’s own interests (quiescent silence beliefs) (Adamska & Retowski, 2012). Silence beliefs are shared by employees who may even discuss when, what and with whom it is wise and effective to exchange information and opinions (Detert & Edmondson, 2011; Knoll et al., 2021; Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Nechanska et al., 2020).

THE ETHICS OF JUSTICE AND SELF-CENSORSHIP

The ethics of justice defines a mode of making decisions in terms of universal principles and rules (Botes, 2001). The final decision is to be impartial, possible to verify and based on the premise of equality: everyone should be treated the same (Rawls, 1999). The rational process of deciding requires the use of procedures, set out in detail and known to everyone. The immanent part of procedural justice is the possibility to voice objections or innovative ideas, through which influence on the decisional process can be achieved (Folger, 1977; Thibaut & Walker, 1975). The opportunity to openly express an opinion lies at the heart not only of psychological health (Judge & Colquitt, 2004) but at the very idea of democracy (Rawls, 1999). It was demonstrated in organizational studies that the reluctance to speak is reduced when procedures are respected within an organization and when they apply to everyone, regardless of position, but also when decisions are reached on the basis of these procedures (Donaghey et al., 2011). Also qualitative studies have shown that perceived fairness at work is important for enhancing the proneness to speak up (Pinder & Harlos, 2001), and research by Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008), where employees were less silent when they perceived a high level of procedural justice, lends direct support for the procedural justice-self-censorship link.

The psychological basis of fair procedures lies in the individual self (van Prooijen & Zwenk, 2008), so the role of procedural fairness in reducing self-censorship could be explained by reference to self-evaluation processes, activated in the context of potential conflict as a result of challenging relations by openly stated opinions and criticism. This is in line with Rawl’s (1999) assertion that self-respect, with its twin aspects of self-esteem and self-efficacy, is supported by the concept of justice as fairness. The studies confirm this: when the self is salient, fairness issues become more important (Sedikides & Gregg, 2008; Skitka, 2003; Tyler & Lind, 1992; Van den Bos & Lind, 2010). Brebels et al. (2013) conducted a study that showed that self-rumination enhances the influence of fair or unfair procedures on the predilection for future interactions. These results were interpreted in the context of the assumption that procedural fairness serves the purpose of reducing uncertainty (Blader & Tyler, 2009; De Cremer & Sedikides, 2005).

The experience of uncertainty intensifies in the process of communication with supervisors (Overback et al., 2006), and indeed the influence of a superior on employee self-censorship has been the subject of many studies. Exercising procedural justice in the manager’s daily contacts with the subordinates, such as communicating aims, and administering and controlling the processes of achieving them, significantly modifies self-censorship (Donaghey et al., 2011). This supports the claim that self-censorship may be reduced through formal mechanisms of voice (Wilkinson & Dundon, 2017), mechanisms which themselves are effective particularly when taken seriously by managers (Wilkinson et al., 2010).

Hypothesis 1: Procedural justice predicts reduction of employee self-censorship.

Relational ethics and self-censorship. Yet, Sandel (1998) points to the fact that the idea of a non-attached person governed by impartial justice does not harmonize with the social embeddedness of the self. The social approach to justice in organizations has led to the distinction of interpersonal justice, founded on the notion of being respected (Greenberg, 1993). Judgment of interpersonal justice is particularly subject to the intensity of the need to belong to a certain social category (Wenzel, 2000). This, in turn, is modified by status: the lower the status, the greater the meaning attached to interpersonal justice (Chen et al., 2003). The importance of interpersonal justice increases with the activation of the interdependent self, which is characterized by a sense of connectedness with others and by due attention to one’s role within in-groups (Holmvall & Bobocel, 2008). This explains why self-censorship motivated by fear and resignation diminishes if the leader is available to subordinates and genuinely appreciates their voices (Hirak et al., 2012). Appreciation may in turn modify shame, an emotion which, according to Creed et al. (2014), upholds self-censorship.

This positive effect of interpersonal justice can be interpreted in the broader theoretical context of relational ethics, as constituted by the specific characteristics of interaction between individuals, in which they are considered worthy of implementation and reward (Metz & Miller, 2016). Mutual respect (the means to mitigate power differentials), engagement and embodied knowledge become the most important features and are closely linked to the responsibility for another person (Pollard, 2015). According to Hamington (2011), a culture of care fosters fundamental respect in an organization and engages intellectual inquiry: “A corporate culture of care does not suggest that members of the organization must become friends or develop strong relationships. It does suggest that people are attentive to one another as part of a willingness to grow” (Hamington, 2011, p. 245). For Gilligan (2006), the pre-eminent representative of the ethics of care, the voicing of ideas, beliefs, expectations and needs is commensurate with the quality of relations.

Relations with a supervisor are very often evaluated through the lens of relational ethics, exemplified by interpersonal justice (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001), which is rated highly if an employee is treated with courtesy and dignity, and without improper remarks or comments (Colquitt & Rodell, 2015). Employees who do not feel respected by their leader display more behaviors that conflict with the interests of the organization (LeRoy et al., 2012), and the relationship is mediated by negative emotions. By contrast, those who receive respect and care are inclined to exceed the basic requirements of the job and contribute to the effectiveness of the entire organization, even though their behaviors are not formally rewarded (Rego & Pina a Cunha, 2010). This proactivity and engagement is also observed in the field of communication: the unwillingness to share information drops if behaviors of the supervisor convey a signal of concern for the high quality of relations (Gao et al., 2011; Hirak et al., 2012). On the other hand, employees’ self-censorship rises when a supervisor displays aversion to those who speak up (Fast et al., 2014).

The importance of relational ethics in limiting self-censorship is, in the opinion of Donaghey et al. (2011), the result of the managers’ interpretation of voice (not institutionalized voicing rules). Also Bauman and Skitka (2009) point to the situations of strong moral disagreement, in which procedural fairness loses its effects. It does not mean that the authors diminish the role of procedural justice. On the contrary, though caring is an appropriate mechanism through which individuals interact in the majority of situations, it excludes the possibility of impartiality so important in complex social settings (Rumsey, 1997). It could be concluded that both kinds of ethics – the ethics of justice (procedural justice) and relational ethics (interpersonal justice) – are important factors of limiting self-censorship and silence beliefs and relational ethics strengthens the effect of the ethics of justice.

Hypothesis 2: The reduction of employee self-censorship under the influence of procedural justice increases in high interpersonal justice conditions.

Hypothesis 3: The reduction of employee silence beliefs under the influence of procedural justice increases in high interpersonal justice conditions.

PRESENT STUDY

The present study investigates the link between procedural justice, interpersonal justice and self-censorship in organizations. The general view of the relations between employer (as well as employer’s representatives) and employee may take the form of procedural justice judgment. The employee is asked about the scope of influence on the decisions made in the organization, voice opportunity and the consistency with which the decisions are implemented. Transparent rules, to which all employees are subjected, eliminate favoritism and offer a formal path for grievances. This may influence the decision to break self-censorship, reducing fear in the process and ensuring that that voice is heard. This does not, however, necessarily mean that personal perceptions, attributions (the processes by which individuals explain the causes of behaviors and events), informal norms and mutual interests are governed by procedural justice. Procedural justice as a signal of an employer’s positive intentions may be too weak to convince employees that self-censorship is not the proper reaction to perceived problems and difficult situations. Due respect and care may amplify the signal by conveying the message that the addressee is important and that their needs and feelings are considered. Therefore we expect that: Hypothesis 1: Procedural justice predicts reduction of employee self-censorship (Study 1); Hypothesis 2: The reduction of employee self-censorship under the influence of procedural justice increases in high interpersonal justice conditions (Study 2), and Hypothesis 3: The reduction of employee silence beliefs under the influence of procedural justice increases in high interpersonal justice conditions (Study 3).

STUDY 1

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The study participants were 161 employees (80 female and 81 male) from a variety of industries, 70 employed in managerial and 91 in non-managerial positions. The participants were aged between 19 and 57 (M = 35.56, SD = 8.47), and average work experience in the organization equaled 3.95 years (SD = 4.78). Participants in MBA studies completed questionnaires during the class activity of a Human Resources Management course.

MEASURES

Procedural justice. We used the Polish adaptation of the seven-item scale developed by Colquitt (2001) to measure procedural justice (Retowski et al., 2017). Participants answered the questions about ways to receive pay, benefits, evaluations or promotions procedure. The scale included items such as “Are you able to express your views and feelings during those procedures?” and “Are those procedures applied consistently?”. Respondents used a five-point scale from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent) to rate the items.

Employee self-censorship. In order to measure employee self-censorship, two subscales (quiescent and acquiescent silence) were used, as adapted into Polish by Adamska and Jurek (2017) from the Four Forms of Employee Silence Scale developed by Knoll and van Dick (2013). Each of these subscales includes three items describing reasons why participants withhold information regarding problems noticed in the workplace, e.g. “…because of fear of negative consequences” (quiescent silence), “…because nothing will change, anyway” (acquiescent silence). Participants used a seven-point scale from 1 (never) to 7 (very often) to rate all items. A measure of employee silence was composed from these two subscales.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for the variables examined in Study 1. Scale reliability in the current study was assessed using Cronbach’s α. The reliability coefficients for each scale are shown on the diagonal.

Table 1

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for variables under study (Study 1)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Procedural justice | 3.44 | 0.79 | (.83) | ||

| 2. Acquiescent silence | 3.20 | 1.50 | –.42** | (.74) | |

| 3. Quiescent silence | 3.30 | 1.37 | –.35** | .55** | (.85) |

A simple linear regression was calculated to predict quiescent and acquiescent silence based on procedural justice. As expected, procedural justice significantly predicted both the quiescent silence scores, b = –.61, 95% CI [–.86, –.36], β = –.35, t(159) = –4.74, p < .001, and the acquiescent silence scores, b = –.79, 95% CI [–1.51, –.53], β = –.42, t(159) = –5.80, p < .001. Procedural justice explained a significant proportion of variance in quiescent silence scores, R2 = .12, F(1, 159) = 22.50, p < .001, and in acquiescent silence scores, R2 = .17, F(1, 159) = 33.58, p < .001.

In confirming Hypothesis 1, it was found that procedural justice predicts reduction of employee self-censorship. It does mean that a work environment that offers influence over procedures, opportunities for voice and appeals against outcomes plays an important role in reducing self-censorship within the organization. The ethics of justice upheld by the organization contributes to reducing the decision to withdraw from an active attempt to change an undesirable situation. The effect of procedural justice on self-censorship is significant both when the decision to remain silent is motivated by resignation (acquiescent silence) and when it is accompanied by fear of the consequences (quiescent silence). Study 1 confirmed the relation between procedural justice and self-censorship but did not consider the role of interpersonal justice as a manifestation of relational ethics. Study 2 was conducted to test the possibility that in high interpersonal justice conditions the reduction of employee self-censorship under the influence of procedural justice increases.

STUDY 2

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The study participants were 163 employees (136 female and 27 male) from a variety of industries, 74 employed in managerial and 89 in non-managerial positions. The participants were aged between 22 and 60 (M = 37.56, SD = 9.38) with an average work experience in the organization of 15.42 years (SD = 9.52). The group was made up of employees in diverse-sized companies, and in public sector organizations. Respondents completed paper-pencil questionnaires.

MEASURES

Procedural and interpersonal justice. We used the same seven-item scale to measure procedural justice as in the previous study. To measure interpersonal justice, Retowski et al.’s (2107) Polish adaptation of the scale developed by Colquitt (2001) was used. Participants were asked about how they were treated by their managers. The scale included four items such as “Has your supervisor treated you with respect?” and “Has your supervisor treated you with dignity?”. Participants rated each item on a five-point scale from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent).

Employee self-censorship. The same two subscales were used to measure quiescent and acquiescent silence as in Study 1.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the variables examined in Study 2. The reliability coefficients for each scale are shown on the diagonal.

Table 2

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for variables under study (Study 2)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Procedural justice | 2.95 | 0.81 | (.83) | |||

| 2. Interpersonal justice | 4.10 | 0.91 | .58** | (.91) | ||

| 3. Acquiescent silence | 3.47 | 1.76 | –.44** | –.24** | (.84) | |

| 4. Quiescent silence | 3.29 | 1.52 | –.28** | –.01 | .64** | (.84) |

To test the predictions regarding the main and interaction effects of procedural and interpersonal justice on two motives for employee silence, moderated multiple regression analyses were conducted. Following the proposal by Aiken and West (1991), predictors were centered, and the interaction term was computed using these scores. Table 3 shows the results of moderated multiple regression analyses.

Table 3

Summary of results of moderated multiple regression analyses (Study 2)

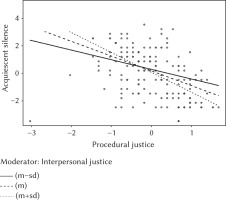

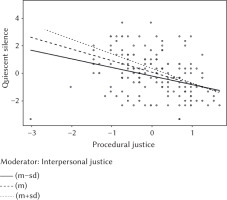

As can be observed, the results show a significant and negative main effect of procedural justice on both acquiescent and quiescent silence, suggesting that organization members self-censor when they perceive low procedural justice within a workplace. Furthermore, there was no significant main effect of interpersonal justice on acquiescent silence, so self-censorship resulting from resignation does not change in the context of respect and care. Further, quiescent silence was positively predicted by interpersonal justice, suggesting that employees who experience the manifestations of relational ethics are more likely to deliberately withhold concerns, information, or opinions about organizational issues. As expected, the interaction between procedural justice and interpersonal justice was significant and negative for both forms of organizational silence. For a better understanding of the character of the interaction effect revealed in the study, regression slopes for low and high interpersonal justice were drawn (see Figures 1 and 2). As can be seen, the negative relationship between procedural justice and acquiescent and quiescent silence was stronger for organization members who scored higher on interpersonal justice.

STUDY 3

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The participants were 386 employees (230 female and 156 male) from a variety of industries, 140 employed in managerial and 246 in non-managerial positions. Participants’ age ranged from 23 to 55 (M = 35.56, SD = 8.47). The study attendants were participating in workshops on the themes of communication in an organization and negotiation. The participants completed paper-pencil questionnaires anonymously at the beginning of each workshop.

MEASURES

Procedural and interpersonal justice. Both organizational justice dimensions were measured using the same scales as in Study 2.

Employee silence beliefs. In order to measure employee silence beliefs, ten items were adopted from Adamska and Retowski’s (2012) Verbalization of the Psychological Contract Scale (VPCS). Five of these items measure quiescent silence beliefs in an organization (e.g. “I have experienced the unpleasant consequences of an honest conversation with the boss”) and five measure the acquiescent silence beliefs in an organization (e.g. “Superiors hear only what they want to hear”). These items are rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

RESULTS

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for the variables under study. The reliability coefficients for each scale are shown on the diagonal.

Table 4

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for variables under study (Study 3)

In order to test the predictions regarding the main and the interaction effects of procedural and interpersonal justice on acquiescent and on quiescent silence beliefs, moderated multiple regression analyses were run. As in the previous study, in order to compute the interaction term, predictors were centered. A summary of the results of these analyses is presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Summary of results of moderated multiple regression analyses (Study 3)

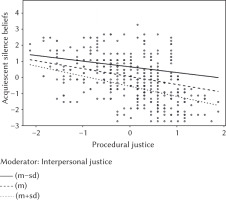

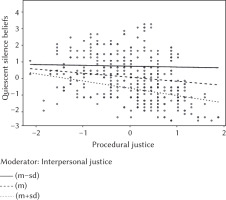

The results of moderated multiple regression analyses showed a significant negative main effect of procedural justice on both acquiescent and quiescent silence beliefs, suggesting that when an organization’s members perceive low procedural justice in the workplace, they are more convinced that their work environment abounds in silence factors. In line with our expectations, there was a significant negative main effect of interpersonal justice on acquiescent and quiescent silence beliefs, suggesting that employees with low expectations of interpersonal justice in an organization are more inclined to believe that relations within the organization do not encourage people to speak up. As expected, the interaction between procedural justice and interpersonal justice was significant and negative for both acquiescent and quiescent silencing belief. Figures 3 and 4 show regression slopes for low and high interpersonal justice. These figures shows that the negative relationships between procedural justice and acquiescent and quiescent silence beliefs were stronger for employees who perceive interpersonal justice relatively highly.

DISCUSSION

We tested in our study the role of interaction of procedural justice and interpersonal justice in reducing self-censorship, understood as the decision to withdraw from speaking, and in reducing employee silence beliefs with regard to specific observations and experiences in the current place of employment. It was found that when employees highly evaluate procedural justice, they declare less self-censorship motivated by fear and resignation (see Study 1). Additionally, the results showed that in high interpersonal justice conditions the role of procedural justice in predicting employee self-censorship (Study 2) as well as employee silence beliefs (Study 3) increases. Our study confirms the results obtained by Tangirala and Ramanujam (2008) that with more procedural justice, there is less silence, and also supports the claim of Wilkinson and colleagues (2010) that formal mechanisms of procedural justice are effective particularly when managers treat their subordinates with respect.

It was also revealed that self-censorship motivated by fear of consequences (quiescent silence) was positively predicted by interpersonal justice, while there was no relation between self-censorship motivated by resignation (acquiescent silence) and interpersonal justice. These results can be explained by referring to the broader context of ethics in which procedural justice and interpersonal justice are immersed. Procedural justice represents the ethics of justice, while interpersonal justice is based on the ethics of relation and care. A focus on relationships in the absence of the ethics of justice is associated with a reluctance to disrupt them, which can happen when there is open communication about perceived irregularities (Gilligan, 1982). It is far from easy to report wrong-doings (Jeffries & Hornsey, 2012; Near & Miceli, 1985), to share information with others that may contradict their beliefs (Reimer et al., 2010) or to expose oneself to the danger of exclusion by being treated as a troublemaker (Miceli et al., 2009; Noelle-Neumann, 1993).

Thus our results confirm the idea expressed by Paley (2002) that ethics of justice is a guard of an ethics of care when “it has gone too far”, that is when caring about relationships leads to self-censorship on issues that need to be changed. This is the case only when an employee’s decision is dictated by negative emotions (quiescence silence) but not when self-censorship is motivated by resignation (acquiescence silence). Resignation is a mental state devoid of emotions mainly due to the fact that previous efforts to change the situation have proved ineffective, so the decision to keep silence is a rational conclusion drawn on the basis of experience (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). Active and defensive quiescence silence (Pinder & Harlos, 2001; Van Dyne et al., 2003) is an inner state which could be more susceptible to relational aspects of contacts with supervisors than to the importance of substantive objections to certain events and wrongdoings in the organization, including behaviors of the supervisor. While this may be a speculative interpretation of the results obtained, it could nonetheless be supported by concepts related to the role of emotions in speaking up (Grant, 2012) and theories and research on group integrity (Esposo et al., 2013; Packer, 2014).

Our study was based on the supposition that ethics of justice and relational ethics complement each other in the domain of self-censorship, and the results duly confirm this theoretical expectation. Respect and concern for relationships under conditions of high procedural fairness reduces self-censorship. Additional studies are necessary to verify this conclusion. Our study should also be developed to explore more effectively the subjective aspect of procedural justice. The participants of the study judged procedural justice in their organizations and were not differentiated according to their susceptibility to justice. It may be the case that those with a pronounced awareness of the sense and meaning of procedural justice are responsible for the strong negative correlation between procedural justice and self-censorship. This line of reasoning is supported by studies on the relation between the need for autonomy and procedural justice: those who are deprived of autonomy are also more sensitive to the manner in which authority figures treat them (van Prooijen, 2009). Likewise, lower status could lead to increased cognitive accessibility of fairness (van Prooijen et al., 2002).

One further aspect of the link between interaction of the two types of ethics and self-censorship calls for scrutinization, that is the climate of silence: a socially shared belief about the sense of influencing the situation through voice (Morrison et al., 2011; Perlow & Repenning, 2009). This belief is rooted in the informal set of rules which regulates communication behaviors. Although our study has partly addressed this aspect by measuring employee silence beliefs, our focus was on individual rather than shared beliefs; hence the latter can only be presumed. There is also an important contextual factor related to shared beliefs, namely national culture. Cultural differences should be included in future studies since the meaning and function of silence varies between individualistic and collectivistic cultures (Botero & Van Dyne, 2009; Covarrubias, 2007; Kawabata & Gastaldo, 2015; Morrison et al., 2004; St. Clair, 2003). The control of emotions through acts of suppression has negative psychological effects in countries with more individualistic cultures, while no such relationship occurs in collectivistic countries (Ford & Mauss, 2015). As self-censorship requires the suppression of emotions in response to negative events in the organizational environment, it may be beneficial if cultural values are controlled in future studies in order to determine whether the strengthening of procedural fairness with interpersonal justice is a universal factor, irrespective of culture, in the reduction of self-censorship.