BACKGROUND

The family systems theory emphasizes that individuals are affected by their family of origin and that patterns of emotions, beliefs, behaviors, and problems are transferred across generations as well as through genetic traces (Bowen, 1978). According to Bowen (1978), individuals can function if they are able to balance their emotional system with their intellectual system, which will involve breaking symbiotic bonds with the family and affirming their need for individuality while balancing this with the need for coexistence (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Differentiated individuals require a differentiated family system. However, where there is an imbalance in the expression of individuality, there is likely to be an emotional cutoff, where the individual will manage unresolved issues by emotional withdrawal from others. Alternatively, if the imbalance is in the direction of togetherness, there is likely to be a fusion between family members where the individual is unable to make their own decisions. The interactional patterns of the family are defined by these alternating levels of autonomy and togetherness.

According to Kerr and Bowen (1988), the family represents an emotional “space” within which its members contribute and interact at various levels. The emotional functioning of individual family members affects the functioning of every other member of the family. According to Bowen (1978), although family relationships and family bonds will differ between cultures, the need for both individuality and togetherness in a family system is indisputable in every culture.

Furthermore, the differentiation of individuals will vary according to the measure of their belonging, communication, and family bonds (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). The level of differentiation may differ. A high level of differentiation indicates that individuals know themselves very well and accept themselves as they are. In situations of anxiety and stress, such individuals may remain reasonable and level-headed. They are able to cope with stress without reducing their functionality. They are more rational and logical and consider various perspectives when solving problems.

Bowenian theory highlights the significance of differentiation by stating that an appropriate distance between family members encourages the establishment of the correct balance between individuality and togetherness (Anderson & Sabatelli, 1990; Bowen, 1978; Garbarino et al., 1995; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998).

DIFFERENTIATION OF SELF

Differentiation of self is one of the cornerstones of Bowen’s family systems theory (1978). Differentiation of self takes place at two levels, internal and interpersonal. It is a process by which the individual separates emotion and thought at the internal level and then activates them at the interpersonal level through establishing a balance between autonomy and intimacy whereby the “self” is maintained despite strong ties. Differentiation of self highlights another aspect of the relationship established with parents when the emotional responsiveness of the person toward their family of origin can be extended to new relationships (Titelman, 2008).

Hence, differentiation of self can be considered an essential characteristic of healthy family functioning. Furthermore, differentiation of self is significant to the maturity and psychological resilience of the individual (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998; Skowron & Schmitt, 2003). The concept of differentiation can be addressed both as an individual variable and as a system variable (Licht & Chabot, 2006).

Differentiation of self can be defined as the individual’s ability to be aware of his or her emotions and thoughts and then to act in a manner that maintains their balance while also investing him- or herself in intense relations (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Individuals with a low level of differentiation have trouble making decisions because they are unable to separate their thoughts from their feelings in order to make clear decisions in emotionally charged situations (Kerr & Bowen, 1988).

The literature indicates that differentiation of self is closely related to stress and anxiety (Lampis et al., 2020; Moon & Kim, 2020). According to Bowen (1978), an environment with high levels of stress and anxiety will tend to create individuals who have low levels of differentiation. Studies reveal that individuals with a low level of differentiation experience greater anxiety (Peleg-Popko, 2002; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998) and psychological distress (Murdock & Gore, 2004; Peleg-Popko, 2002; Peleg & Rahal, 2012; Ross & Murdock, 2014). In contrast, it has been noted that individuals with higher levels of differentiation have more positive relationships (Gharehbaghy, 2011), and they are more satisfied in life and their general level of well-being is higher (Biadsy-Ashkar & Peleg, 2013; Jankowski & Hooper, 2012; Jankowski & Sandage, 2012; Ross & Murdock, 2014; Yousefi et al., 2009).

MEASURING DIFFERENTIATION OF SELF

Since Bowen (1978) first introduced the concept of differentiation of self, many measurement tools with varying dimensions have been used to measure this differentiation. Initially, Bowen (1978) measured differentiation on a scale ranging from 0 and 100. He stated that a score between 0 and 25 indicated that the differentiation of an individual was very low, and they would experience many life problems. Individuals in the range between 25 and 50 also live in a world dominated by feelings, despite their capacity for differentiation being greater. Bowen asserted that individuals in the range between 50 and 60 still have challenges in their relationships even though they are able to separate their feelings from their thoughts. In contrast, people whose scores are over 60 are able to separate their emotions from their thoughts and can express their own beliefs without being defensive. Bowen (1978) stated that the closer the score is to zero, the greater is the fusion. Bowen (1978) later suggested that at the other end of the scale, after 100, differentiation might go to 0 again. Emotional cutoff takes place on this end of the scale.

Haber (1984) developed a 24-item, one-dimensional Level of Differentiation of Self Scale to empirically test the concept of differentiation of self and to assess the extent to which level of differentiation affects the relationship between a husband and wife. Subsequently, Skowron and Friendler (1998) developed a Differentiation of Self Inventory to measure differentiation of self at both the internal and interpersonal level. These authors conducted three studies with a total of 609 adults, older than 25 years, and confirmed that their findings were consistent with Bowen’s theory, which meant that their inventory was capable of measuring Bowen’s original concepts. Skowron and Schmitt (2003) revised the “fusion with others” sub-dimension of this inventory. In a study conducted with 225 participants, the items of the “fusion with others” sub-dimension were shown to evaluate interpersonal fusion more effectively than the previous version. Drake et al. (2015) developed a short form of the same scale for ease of use by researchers and professionals. After validity and reliability studies had been performed, the Differentiation of Self Inventory was reduced from 46 items to 20 items. The Differentiation of Self-Inventory Short Form now consists of 20 items divided into four sub-sections. The usability of this scale was demonstrated with a group of 3,000 university students (Drake et al., 2015).

In addition to these measurement tools, which focus on both the intrapsychic and interpersonal dimensions of the differentiation of self, some studies have focused only on the interpersonal dimension of differentiation. Bray et al. (1984) developed the 181-item Personal Authority in the Family System Questionnaire, consisting of 7 sub-dimensions to measure personal authority in inter-generational family processes. Another measurement tool used to measure the systemic dimension of differentiation is the Differentiation in the Family Scale, developed by Anderson and Sabatelli (1992). This consists of 11 items using a 5-point Likert scale, and it is applied separately for the following relationship pairs: mother/father, father/mother, mother/self, father/self, self/mother, and self/father. On this scale, higher scores are considered as indicating a higher level of differentiation or greater tolerance for individuality. In addition to these scales, a family-of-origin scale (Hovestadt et al., 1985) and the Emotional Cutoff Scale (McCollum, 1991) were developed to assess differentiation from the family system. The Crucible Differentiation Scale, developed by Schnarch and Regas (2012), consisting of 63 items and seven factors, also measures differentiation by focusing on important relationships. It can be assumed that these measurement tools concentrate on the level of differentiation in the interpersonal relationships of the individual.

INTRAPSYCHIC ASPECT OF DIFFERENTIATION OF SELF: EMOTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION

Bowen (1978) discusses the concept of differentiation of self both from the perspective of interpersonal relations and from the intrapsychic perspective, which emphasizes the process of distinguishing thoughts from feelings. It is understood from the literature that the concept of differentiation of self is generally handled in terms of interpersonal relations, while the aspect of distinguishing feelings from thoughts is more often neglected when developing measurement tools. Differentiated family systems will create differentiated individuals. From this perspective, the term differentiation will refer not only to the separation of individuals from their relationships but also their ability to act out of a balance between emotions and thoughts. However, the concept of emotional differentiation differs from the relational dimension of differentiation and focuses solely on the intrapsychic section. In other words, emotional differentiation is another name for the intrapsychic dimension of the differentiation of self. Intrapsychic differentiation enables the individual to experience strong affect and yet to shift to calm and logical reasoning as the situation requires (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998).

Individuals feel many emotions, such as guilt, shame, disapproval, anger, anxiety, jealousy, enthusiasm, sympathy, and rejection. Feelings greatly affect human behavior and relationships. The intellect, on the other hand, describes the thinking part of individuals and expresses their capacity to know and understand (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). When acting mostly under the promptings of their emotions, individuals tend to close their eyes to the existence of the alternatives in their lives. Their behavior typically includes intense emotional reactivity. Therefore the decisions they make are largely aimed at calming their emotions. These emotionally undifferentiated individuals can be extremely destructive both to themselves and others, especially in times of stress. Sometimes they blame themselves, and sometimes they hold another person responsible for their problems. At the other extreme are those individuals whose actions are guided only by their own thoughts and who act out of knowledge and beliefs. This can, sometimes, include holding blindly on to the opinions of a group. Persons who are emotionally differentiated are free to feel their emotions and yet also are able to act logically, making their own decisions (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Emotionally differentiated individuals will sometimes act on their emotions, but when a problem arises, they can manage their anxiety, take control of the situation, and prevent it from becoming a life crisis. In such a situation, stress and anxiety are maintained at a tolerable level.

Anxiety manifests itself through physical, psychological and social symptoms. Differentiation is closely related to how life stress is managed. Empirical studies have shown that individuals with low differentiation levels experience greater stress and anxiety. In a study with a sample group of 47 people seeking treatment for anxiety and a control group, Lampis et al. (2020) found that lower I-position levels and higher levels of emotional cutoff and fusion with others were associated with higher levels of anxiety-related problems. Moreover, emotional detachment and fusion with others were found to be predictors of the likelihood of seeking support for anxiety disorders. In a study with 1,192 Korean college students, Moon and Kim (2020) found that self-differentiation and self-efficacy were negatively correlated with stress and depression. However, the “explanatory power of self-differentiation with stress was 23.9% on depression, demonstrating partial mediated effect of self-differentiation in the relationship between stress and depression” (Moon & Kim, 2020, p. 151).

Chabot (1993) developed a self-report tool, the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale (CED), that aimed to measure individuals’ ability to distinguish between emotional and intellectual functioning and to utilize their intellect in emotionally charged situations. This tool was created to compensate for the widespread neglect of the intrapsychic aspect of Bowen’s differentiation of self in the existing measurement tools. The scale includes items that ask individuals to indicate their level of intrapsychic differentiation in relation to four different conditions: a) non-stressful periods, b) a continuously stressful period, c) when relations go well, d) when difficulties occur in relationships. Each item is structured so as to assess the individuals on the basis of how well they balance their emotions and thoughts. The theoretical background and psychometric properties of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale were later explained by Licht and Chabot (2006).

The current study aimed to adapt the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale for Turkish use and to conduct the necessary validity and reliability study. This means that when this scale is introduced through the Turkish literature, studies on the differentiation of self will be able to address both aspects, which will provide a valuable guide for researchers and for clinicians working not only in the field of family and couple therapy but also in individual dynamics.

MEASURING EMOTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION: CHABOT EMOTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION SCALE

The Emotional Differentiation Scale consists of 17 items which distinguish between thought and emotion in the context of the differentiation of self. The items are evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The total score for the scale varies between 17 and 85, with a higher score indicating greater intrapsychic differentiation.

Twenty-three undergraduate students between the ages of 17 and 21 years were included in the first pilot study (Takagishi, 1996) to test the reliability of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale. In this study, the reliability coefficient of the scale was found to be .66, while the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the scale was found to be .70. Since two of the original 20 items had negative correlations, these items were removed from the scale, after which the new Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient was calculated to be .80. Other reliability studies conducted on the scale obtained similar Cronbach’s α coefficients, which ranged from .81 to .86 (Franks & Chabot, 2004; Reynold & Chabot, 2004).

Franks and Chabot (2004) discovered that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale related to the Differentiation of Self Scale at a level of .62. When the sub-dimensions were evaluated, they showed a significant relationship between the “I-position” and “fusion with others” sub-dimensions. In a study with young adults leaving home, Takagishi (1999) found that emotional differentiation was a predictor of psychological functionality. Karasick (2004) stated that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale shows a positive correlation with the Differentiation in the Family System Scale and with life satisfaction, positive emotion, and student adaptation. From a study conducted with 112 undergraduate students, Magnotti (2004) concluded that, as emotional differentiation increases, college adjustment increases, but that as triangulation increases, emotional differentiation decreases.

Bellur and Dinçyürek (2020) adapted the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale into Turkish for use in their study of 433 married individuals living in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). As a result of their study, four items of the original scale were removed, and a scale with 12 items and two factors was retained. When the convergent validity of the scale was examined, a moderate negative correlation was found between the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale (CED) and the Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI), and a positive significant correlation was found between the CED and the Married Life Satisfaction Scale (MLSS). Although the researchers did adapt the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale into Turkish, the Northern Cyprus sample is not representative of Turkey. Differences in language and culture are to be expected. Furthermore, only married individuals were included in the adaptation study conducted in the Cyprus sample. The present study was conducted in the Republic of Turkey and participants were selected from all individuals over the age of 18. In this way, the present study differs from the study of Bellur and Dinçyürek (2020) conducted in Northern Cyprus with married individuals only.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study sample consisted of a total of 369 volunteers between 18 and 52 years of age (M = 24.75, SD = 7.15); 279 were women (75.6%) and 90 men (24.4%). They were selected by the convenience sampling method using Google Forms in 2020. Of the participants, 86.7% (n = 320) stated that they were single and 13.3% said they were married (n = 49).

MEASURES

A Personal Information Form, the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale (CED), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-42), and the Differentiation of Self Inventory-Short Form (DSI-SF) were used in the study.

Personal Information Form. This was the form prepared by the researcher, which included questions to obtain demographic information and to ascertain the gender, age and marital status of the participants.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-42). This scale, developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995), consists of 42 items that measure depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms as experienced in the past week. Each sub-dimension of the scale (depression, anxiety, stress) is represented by 14 items. Items are evaluated on a 4-point Likert type scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applies to me very much). High scores on the various subscales indicate high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. In the original study, the normal range was 0-9 for depression, 0-7 for anxiety and 0-14 for stress. Cutoff scores were calculated as 10 for depression and 7 for anxiety in the Turkish adaptation study. A study on the Turkish adaptation of the scale was first performed by Uncu et al. (2006), and the psychometric characteristics of the scale were later investigated by Bilgel and Bayram (2010). The Cronbach’s α internal coefficient for depression in this study was found to be .92, while it was found to be .86 for anxiety, and .88 for stress.

The Differentiation of Self Inventory-Short Form (DSI-SF) was developed by Drake et al. (2015) to provide a shorter version of the differentiation of self scale, and it is based on the DSI-R, which consists of 46-items. The DSI-SF scale consists of only 20 items with four sub-dimensions: “I-position”, “emotional reactivity”, “fusion”, and “emotional cutoff”. Items are evaluated using a 6-point Likert type scale from 1 (does not reflect me at all) to 6 (highly reflects me). Sarıkaya et al. (2018) conducted an adaptation, validity, and reliability study on the scale in Turkish. As a result of confirmatory factor analysis, acceptable goodness of fit values were reached, and the four-component structure of the DSI-SF was established. Furthermore, the results obtained from the correlation analysis reveal that the scale ensures convergent validity. The Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient was found to be .82.

THE PROCESS OF ADAPTATION OF THE SCALE

The original Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale was translated by three experts in the field of science of psychology, who were competent in both English and Turkish, before the adapted scale was applied. The research team evaluated three translations and from them created a single form. Subsequently, three different experts back-translated this form from Turkish into English. The research team examined the translations, and the Turkish version was then finalized. The face validity of the scale was tested by administering it to 10 experts. The scale was then administered to volunteers using applications such as e-mail, Facebook, and WhatsApp. An informed consent form was included at the start of the scale. In the informed consent form, participants were asked to write their e-mail addresses, and they were asked if they were prepared to participate in the test-retest process, which would constitute the second stage of the research. Two weeks after this group of volunteers had been approached, the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale was administered to them, together with the Demographic Information Form.

DATA ANALYSIS

The data obtained were analyzed using the SPSS-22 and AMOS-22 package programs. The suitability of the data to the adapted scale was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. To test the validity of the scale before reviewing its psychometric characteristics, the structure and convergent validity were examined. Together with the construct validity of the scale and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, reliability was examined using the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient, the test-retest method, and item analysis.

RESULTS

VALIDITY

Face validity. Face validity indicates what the measuring tool appears to measure, not necessarily what it actually measures. The face validity of a scale refers to the extent to which the scale appears to measure the property that it is intended to measure. The face validity of the scale should be increased in some cases and concealed in others (Ercan & Kan, 2004).

To test for face validity, after translations, the finalized form was applied to a small sample group of 10 experts to determine whether there were any linguistically incomprehensible expressions. These 10 experts consisted of research assistants from the psychology department of the university where the researcher was working. Feedback was received from these experts about the comprehensibility of the scale and whether the scale measured the desired feature. The data collection phase was initiated after a subsequent correction.

Construct validity. Although Licht and Chabot (2006) revealed a single-factor structure for the Emotional Differentiation Scale as developed by Chabot (1993), neither of these studies assessed the factor structure of the scale. Hence, in the current study, exploratory factor analysis was used to evaluate the factor structure of the scale.

EXPLORATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS

Exploratory factor analysis was performed first to discover the factor structure of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale. The suitability of the data for factor analysis was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) coefficient and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Bartlett’s test of sphericity evaluates the existence of correlations between the variables. If the KMO value is higher than 0.60 and the Bartlett’s test is significant, it means the data are suitable for factor analysis (Büyüköztürk, 2004). The KMO sample adequacy value was found to be .88 and the Bartlett’s sphericity test value χ2 was found to be 1713.33 (p < .001). These results revealed that the sample size was adequate, and the data distribution was suitable.

After collecting the evidence that the dataset was suitable for factor analysis, factor analysis was applied to the data collected from application of the scale. The Varimax technique was used in the principal axis factor analysis for the research. Furthermore, the breaking point of the scree plot was taken into account in defining the structure. Factors with an eigenvalue above one were considered significant and were taken into consideration when evaluating the results. In the study of factor loadings, 0.30 was considered to be the minimum value (Büyüköztürk, 2004; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). However, the 14th item, which had a factor loading of –0.2 (“I prefer work relationships to intimate relationships because there is a clear separation between feelings for, and responsibilities to, each other”), was removed.

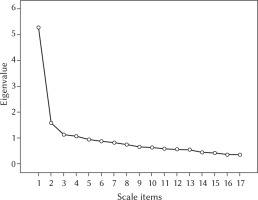

When the scree plot graph of the factor eigenvalues as presented in Figure 1 was reviewed, it became evident that there was an extremely accelerated decrease after the first factor. This can be interpreted as the scale presenting a single factor structure. The factor loadings of the scale are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1

Demographics

Table 2

Exploratory factor loadings of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale

| Item | |

|---|---|

| Item 7 | .70 |

| Item 11 | .69 |

| Item 10 | .68 |

| Item 8 | .67 |

| Item 12 | .62 |

| Item 4 | .62 |

| Item 3 | .61 |

| Item 16 | .59 |

| Item 6 | .58 |

| Item 13 | .57 |

| Item 15 | .52 |

| Item 2 | .52 |

| Item 9 | .50 |

| Item 5 | .44 |

| Item 1 | .43 |

| Item 17 | .33 |

| Total variance explained | 31% |

| Eigenvalue | 5.28 |

The results of the exploratory factor analysis revealed that the scale had a single factor structure that explained 31% of the total variance with an eigenvalue of 5.28. Factor loading values of the scale varied between .33 and .70. According to Büyüköztürk (2004), explained variance of 30% or more can be considered sufficient in single-factor scales.

CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS

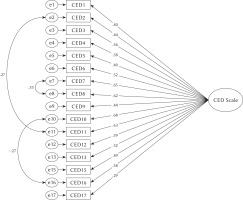

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the construct validity of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale. According to the preparatory results of the CFA, which was performed considering the previously mentioned criteria, the goodness of fit indices (GFI) of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale were perceived to be lower than the critical value. Furthermore, it was noted that the modification indices between items 2 and 11, 7 and 8 and 10 and 16 were moderately high. Bearing this in mind, CFA was repeated after modifying these items. The results of the CFA are presented in Figure 2.

It was determined that because the standardized factor loadings varied between .29 and .68, all factor loadings were significant. The acceptable fit value for the GFI, CFI, NFI, RFI, IFI and AGFI indices is specified as .90. For RMSEA, .08 is regarded as an acceptable fit (Bentler, 1980; Bentler & Bonett, 1980).

It was observed that the goodness of fit indices of the scale were as follows: χ2(61, N = 369) = 249.32, χ2/df = 3.00, GFI = .90, SRMR = .060, RMSEA= .070. It was concluded that the goodness of fit indices of the single-factor structure of the scale were acceptable, according to these criteria. Table 3 presents the findings indicating whether the results of the confirmatory factor analysis met the criteria.

CONVERGENT VALIDITY

The relationships between the Depression Anxiety and Stress-42 Scale (DASS-42) and the Differentiation of Self Inventory-Short Form (DSI-SF) were reviewed to test the validity of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale.

Simultaneously, the correlation between the scores obtained from the developed scale and the specified criteria was evaluated for convergent validity (Ercan & Kan, 2004), reliability and validity of the scales. In this context, in order to test the convergent validity of the scale, the Differentiation of Self Inventory-Short Form (DSI-SF), which is another measurement tool for differentiation, was expected to show a positive correlation between the I-position, emotional cut-off, emotional reactivity, fusion and the other dimensions. It is important to note that higher scores on all subscales indicate greater differentiation. In addition, in order to test the divergent validity, the variables of depression, anxiety, and stress, which were expected to show a negative correlation with emotional differentiation, were analyzed.

In addition to the total scores for the CED and DSI-SF, the scores for the I-position, emotional reactivity, fusion, and emotional cutoff sub-dimensions and the relationship between the sub-dimensions of DASS-42, namely depression, anxiety, and stress, were included in the analysis. The results indicating the convergent validity are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

Concurrent validity results of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale

| Variable | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | I-position | Emotional reactivity | Fusion | Emotional cutoff | DSI-SF Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CED | -.55** | -.54** | -.54** | .68** | .60** | .64** | .17* | .69** |

As can be seen in Table 4, the CED had a significant negative relationship with depression (r = –.55, p < .001), with anxiety (r = –.54, p < .001) and with stress (r = –.54, p < .001) among the sub-dimensions of DASS-42.

However, the CED had a significant positive relationship between the total score for DSI-SF (r = .69, p < .001), I-position (r = .68, p < .001), emotional reactivity (r = .60, p < .001), fusion (r = .64, p < .001) and emotional cutoff (r = .17, p < .01).

If we consider all these results, it is possible to state that the convergent validity of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale is also verified.

RELIABILITY

Participants were asked to write their e-mail addresses if they wanted to participate in the retest, which is the second stage of the research. Two weeks after the application in this group of volunteers (n = 30), the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale was applied together with the Demographic Information Form. To ascertain the reliability of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale, the test-retest reliability coefficients were calculated with Cronbach’s α, and item analysis was performed. Consequently, the results regarding the test-retest reliability coefficients and Cronbach’s α are displayed in Table 5. Furthermore, Table 5 presents the corrected item-total correlations for the items of the CED.

Table 5

Reliability results of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale

As can be observed from Table 5, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale is .86 and is therefore at an acceptable level. Similarly, the test-retest reliability coefficient is .76. It can thus be stated that the scale has a sufficient reliability coefficient.

According to the findings on the item analysis of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale, it was observed that corrected item-test correlations (.27 and .61) were altered, and the corrected assumptions were tested and ensured according to the regression analysis. As a result of all these reliability analyses, it can be confirmed that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale has sufficient reliability.

Consequently, it can be confidently stated that the Turkish version of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale is a measurement tool consisting of 16 items with a single factor structure, which is scored between 1 and 5. In the Turkish version of the scale, the 14th item was removed from the scale due to its low factor loading. The items numbered 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 11, 15 and 16 are reverse coded. The lowest score that can be obtained from the scale is 16, while the highest score is 80. When individuals obtain a high score for the scale, it indicates that they are able to establish a stable balance between their feelings and their thoughts, and that they are able to make logical judgments even under compelling emotions, that is, they are more emotionally differentiated. It is concluded that, with its current psychometric characteristics, the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale is a valid and reliable instrument that can be used to measure the concept of emotional differentiation in a sample of Turkish adults aged 18 years and over.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to measure the intrapsychic aspect of the differentiation of self in the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale, which was developed by Chabot (1993), while its psychometric characteristics were later specified by Licht and Chabot (2006). This study also aimed to adapt the scale for use in Turkey and conduct a validity and reliability study on the Turkish version. To this end, the validity of the scale was examined by exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and convergent validity methods, and its reliability was analyzed by the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient, test-retest reliability coefficient, and item analyses. Item 14 had a factor loading lower than 30 and was therefore removed from the Turkish scale. Confirmatory factor analysis results verified the single-factor structure and the fit indices were determined to be acceptable (Bollen, 1989; Hooper et al., 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993).

In their Turkish study on married individuals living in the TRNC, Bellur and Dinçyürek (2020) stated that their scale revealed a two-factor structure. The two factors revealed in their study conducted in a Northern Cyprus sample are not consistent with the single-factor structure of the original scale, and the resulting sub-dimensions of the I-position and emotional reactivity seem to be more related to the interpersonal side than to the intrapsychic side, as differentiated by the Bowen family systems theory. I-position and emotional reactivity suggest that the scale is more related to interpersonal differentiation than to emotional differentiation. Furthermore, as stated earlier, Turkey and Northern Cyprus are two separate regions with different cultural characteristics, although the Turkish language is spoken in both. Therefore, it can be stated that the findings of the present study confirm the single-factor structure for the use of the scale in Turkish culture.

A negative relationship between depression, anxiety, and stress was identified when the convergent validity of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale was considered. In other words, as the emotional differentiation of individuals increases, their depression, anxiety, and stress levels decrease. Likewise, Takagishi (1996) discovered that the Emotional Differentiation Scale showed negative correlations with depression and anxiety in a study conducted with undergraduate students. Karasick (2004) also ascertained that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale correlated negatively with negative emotions.

The Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale was found to correlate positively with the total score for DSI-SF and with the I-position, emotional reactivity, fusion, and emotional cutoff subscales. Thus, it can be assumed that, as the self-differentiation scores of individuals increase, their emotional differentiation also increases. It can be concluded that the findings of the study regarding convergent validity confirm the literature showing that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale has a positive relationship with psychological functionality, while it correlates negatively with negative mental health variables (Franks & Chabot, 2004; Karasick, 2004; Takagishi, 1999).

When the previous reliability values of the scale were examined, Takagishi (1999) calculated the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale as .80; in a study conducted with 166 university students, Karasick (2004) identified the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the scale to be .76, while Franks and Chabot (2004) stated that the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient was .86. A study conducted with Italian nationals and Italian-American university students (Reynolds & Chabot, 2004) revealed the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient to be .81. It is therefore evident that the scale has comparable levels of reliability in various studies. In the study using a Turkish adaptation of the scale conducted previously in Northern Cyprus, the Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient was found to be .74.

When the findings regarding the reliability of the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale are reviewed, it can be ascertained that the Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient is over the acceptable level (α = .86); and the test-retest reliability coefficient is equal to .76. These results show that the scale is a reliable instrument for use in a Turkish sample.

CONCLUSION, LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The psychometric properties revealed in this study show that the Chabot Emotional Differentiation Scale is a valid and reliable measurement tool that can be used in the measurement of emotional differentiation in a Turkish sample with adults aged 18 and over. One of the limitations of this study is that the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the same group. The reason for this is that although the scale showed a one-dimensional structure in its original form, the researchers who developed the scale did not perform an exploratory factor analysis, so the structure had to be tested for exploratory factor analysis before the confirmatory factor analysis. However, in future studies, it will be useful to test the structure to be confirmed by exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis on different samples. One of the strengths of the study is the large sample of individuals over the age of 18, rather than a specific age group. However, the fact that fewer than 25% of the sample consisted of men can be considered a limitation of the study. For this reason, it will be useful to re-examine the psychometric properties of the scale in Turkish culture with a sample consisting predominantly of men.

Emotional differentiation can be considered an important variable for mental health. Previous studies have shown that individuals may experience internal and relational problems when they cannot balance their emotions and thoughts, in other words, when they cannot achieve emotional differentiation. With the adaptation of this scale into Turkish, empirical studies to identify possible variables that could affect emotional differentiation can be performed in the Turkish population. Likewise, the obstacles to emotional differentiation and the consequences of non-differentiation can also be determined. The fact that emotional differentiation can be studied in a Turkish sample will contribute to the existing literature with respect to the universality of the Bowen family systems theory.

At the same time, emotional differentiation is also an important issue in psychological counseling and psychotherapy. Although many counselors or therapists can see that individuals fail to balance their emotions and thoughts when facing problems, the concept of emotional differentiation has been given insufficient attention in the therapy literature. The aim of the present study is to draw attention to the concept of emotional differentiation. Individual intervention techniques or group intervention programs on how to achieve emotional differentiation in individuals in the course of psychological counseling and psychotherapy can be considered and planned.